'Secrecy no more.' Under court order, Shasta County releases sheriff's office records

An investigation into wrongdoing in the Shasta County Sheriff's Office, kept secret for two years, reveals an agency that was riven with mistrust under a leader who admitted he violated a state law, allegedly bragged about working with a local militia group, and claimed to defy the county Board of Supervisors, the now-released documents show.

The report confirmed that former Sheriff Eric Magrini had joked about provoking protesters into burning down a "dilapidated" South County Patrol Station during social justice demonstrations in Redding in June 2020.

Magrini drew a map from the Martin Luther King Jr. Center in Redding to the sheriff's South County Patrol Station and marked it "Precinct 3," in reference to a Minneapolis police precinct burned during George Floyd protests, the report says. The map was shared with others in the department.

If protesters were going to burn down a building, Magrini said, it should be the South County Patrol Station, according to what became known as the Ellis Report.

Magrini joked about further inflaming demonstrators by drawing a Hitler mustache on a photo of a captain in the office and sending the photo to other department employees, according to the report. The photo was not shared with the public, according to the report. Officers called the jokes “immature” and inappropriate, considering the tensions in the community and nature of the demonstrations, the report says.

While Magrini publicly denied he invited members of a Shasta County militia to provide security during the protests, the report said Magrini actually coordinated with the paramilitary group and bragged to officers in his department about having the militia's members “one call away” if the lawful demonstrations became violent.

More: How we got here: The two-year effort to obtain records from Shasta County

The sheriff broke state law by using a law enforcement communications tool known as the California Law Enforcement Telecommunications System, or CLETS, to illegally obtain criminal background information on job candidate Matt Pontes before the Board of Supervisors hired Pontes as county executive officer in January 2020, the report says.

And Magrini used federal COVID-19 pandemic relief money to buy television sets for his own and his undersheriff’s offices, according to the report.

Findings of the investigation into the operations at the sheriff’s office were among the thousands of county documents released to the Record Searchlight earlier this month after a Shasta County judge ordered county officials to hand over the records to the newspaper under the California Public Records Act.

Obtaining findings from the months-long investigation into the sheriff’s office in 2021 was the main reason the Record Searchlight filed a lawsuit against county officials in 2022.

"Our readers can finally examine the findings of an investigation into the highest levels of the Shasta County government. They can come to their own conclusions about those findings. One thing is certain — it should not have taken this long for a full accounting of the Ellis Report and related documents to be made public," said Silas Lyons, director of Gannett's Center for Community Journalism. Gannett is the parent company of the Record Searchlight.

That investigation's findings, contained in the Ellis Report, related to 15 accusations made against Magrini by the Sheriff’s Administrative Association, a union made up of captains and lieutenants in the department.

Even though officers in his department ― from captains down to sergeants and deputies ― had passed votes of no-confidence in Magrini's leadership, the outside attorneys hired by the county to compile the Ellis Report concluded that he wasn't the cause of a “toxic” environment in the department.

By contrast, the Sheriff's Administrative Association went so far as to threaten to report issues in the department to the state Attorney General's Office or begin recall proceedings against the sheriff.

Ellis Report raises questions beyond its findings

While the Ellis Report's authors determined four of the allegations made by sheriff's department staff had merit, other findings raised questions about how the department operated during Magrini’s one-and-a-half years in the county's top law enforcement job.

The report found that Magrini told officers in his department that he would not comply with a Board of Supervisors request to send 15 deputies to a board meeting in January 2021, a period when rancor steadily interrupted many board meetings as some members of the public objected strongly to COVID-19 restrictions.

Magrini refused the board's request because he was angry at its members for not giving him a pay raise, the report said.

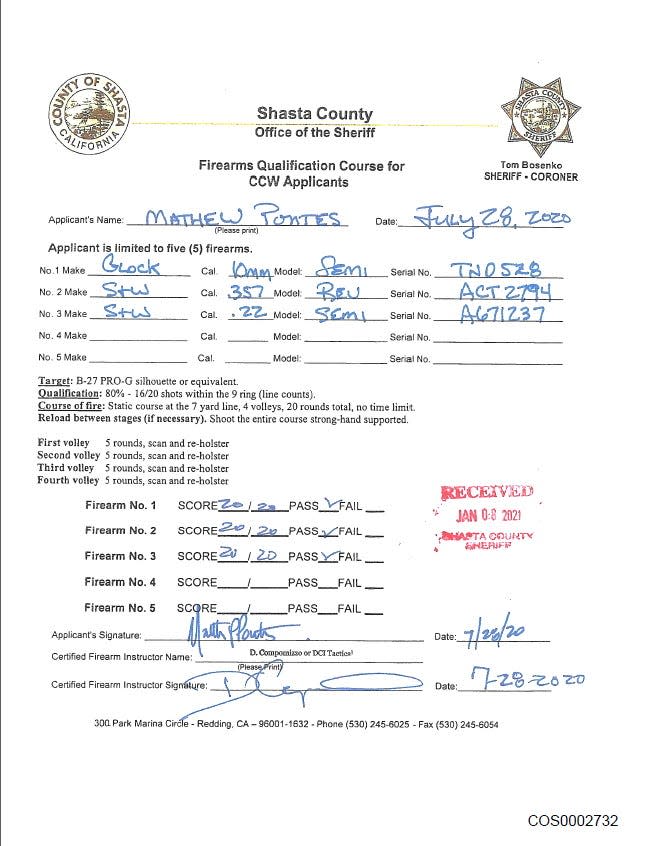

In a separate incident, investigators concluded that Magrini's office had been involved in unduly assisting Pontes, despite the alleged misuse of a state system to criminally background Pontes before he was hired. While he worked for Shasta County, Pontes’ application for a concealed carry weapons permit — which the sheriff’s office would approve — appeared to have the mandatory in-person shooting portion filled out before Pontes even took the test, the report says.

Whatever Magrini’s standing with Pontes, the latter hired the former sheriff as a top executive with the county. The Ellis Report is dated June 2, 2021, just a week before Pontes offered Magrini a 31% pay increase to take the newly-created assistant Shasta County CEO job.

Shortly after the Ellis Report was completed but not released to the public, Pontes spoke highly of the sheriff’s skills, knowledge and leadership abilities.

"He definitely rose to the top. We had a lot of really good applicants, and with the board (of supervisors) and community focused on public safety, I was looking at all of his administrative experience, and he just kind of rose to the top. He's also got a lot of connections in the community," Pontes said at the time.

Pontes quit his job with the county in 2022.

Of the thousands of documents released after the Record Searchlight won its records lawsuit, there were no emails or letters exchanged between county officials and supervisors about other candidates considered for the assistant CEO job.

In fact, no communications of any kind written by board members to county officials were found among the documents released.

The Record Searchlight is naming members of the Shasta County sheriff's command staff, county officials and union leaders in all stories because they are public figures. However, the newspaper is voluntarily withholding the names of other workers and is not publishing the Ellis Report in full in order to balance individual privacy with the public's interest in this case.

Patrick Jones, one of only two supervisors remaining on the board who had served when the Ellis Report was written, said in August that considering the issues going on in the sheriff’s office at the time, it didn’t make sense to hire Magrini as the county's first assistant CEO.

Jones said he favored creating an assistant CEO position but didn’t think Magrini was right for the job.

“I was vocally disappointed and upset that Pontes, through the hiring process, picked Magrini as the most qualified. And I would argue that that isn't the case,” he said.

More: Investigation reveals Shasta County sheriff violated state law, other issues

Jones said he also did not agree with some of the conclusions reached in the Ellis Report, written by the law firm Ellis Investigations.

“Well, clearly when the report said something to the effect if I can remember correctly, that yes, Magrini broke the law when he did a background check on Pontes, but it's OK," said Jones. "I just don't think it's OK. And so I would question their findings," he said.

Even as a member of the Board of Supervisors, Jones said he could not get a copy of the report, but had to sit and read it while former County Counsel Rubin Cruse Jr. watched over him.

“And where's Eric Magrini today? Nowhere to be found. I have no idea where he’s at,” Jones said.

Jones said he was told in May that the former sheriff was on leave and he was not allowed to have contact with him.

Magrini still works for the county, a spokesman said in August. But the spokesman declined to comment further on the assistant CEO’s status.

Magrini did not reply to voicemail messages left on his cell phone.

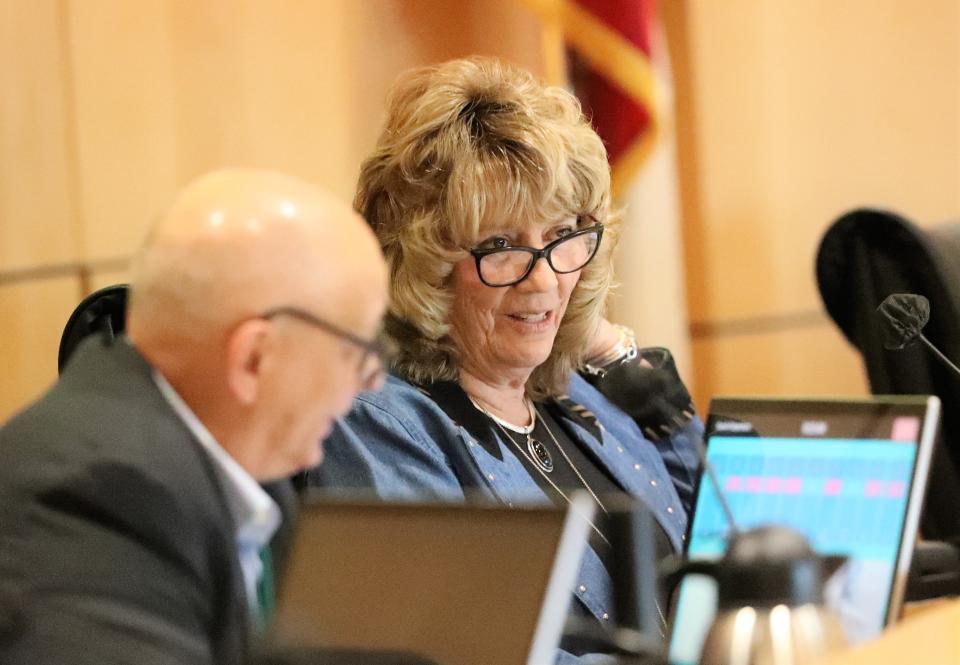

Supervisor Mary Rickert, who also was on the board when the report was written, said she read only a summary of the findings and felt it did not raise any serious issues.

When asked about the tumult in the sheriff’s office then, she attributed that to countywide distress over issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic rather than resulting specifically from Magrini’s department management.

“It was absolute turmoil. I think that was a big part of the turmoil in the department," said Rickert. "From my personal vantage point, there was just a lot of turmoil in general everywhere."

She also said hiring Magrini as assistant CEO made sense at the time because the county wanted to use his law enforcement expertise to coordinate building a new jail, then being proposed to include mental health and addiction treatment services. The county also wanted Magrini to spearhead efforts to stop illegal marijuana growing in the county, Rickert said.

The county has developed a marijuana eradication team and is working on plans to expand the county jail in downtown Redding. The county has not described the services the expanded jail would provide.

Shasta County circumvents public records laws

The Record Searchlight began seeking the Ellis Report and other documents in August 2021, when the newspaper submitted the first of four Public Records Act requests to the county. After county officials refused to hand over the documents, the newspaper filed suit in Shasta County Superior Court last year, asking a judge to order their release.

After the county lost a January 2022 trial and attempted to have a judge reconsider his ruling, it finally handed that information over earlier this month.

"Local newspapers like the Record Searchlight have always been champions of transparency," Lyons said. "We didn’t ask for a lengthy legal fight, and we gave the county multiple opportunities to obey the public records law without needing a court order."

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

Walt McNeill, the newspaper’s attorney in the case, said the two-year effort to obtain the records served a purpose greater than just the revelation of the information in the documents.

“What it does is shine a light on a culture of secrecy and denial in county government,” McNeill said. “And if you don't change that culture from secrecy and denial to one of transparency and recognizing a true obligation to be open with the public about how they run our government departments, then we're going to have these conflicts again and again, and again.”

Indeed, in the Ellis Report, Magrini admitted that he regularly deleted communications to avoid complying with California Public Records Act requests.

“For his part, Sheriff Magrini plausibly explained that it was his regular practice to delete text messages and emails daily and that he started the practice two to three years ago. He explained that he did so because his records were subject to PRA (Public Records Act) requests,” the report says.

The report noted that others in county government also regularly deleted emails and text messages, a process the report said was permitted under the county's electronic records policies.

“Many public organizations had similar practices for various reasons, including mitigating the work involved in responding to extensive and voluminous PRA requests,” the Ellis Report says.

David Loy, legal director for the First Amendment Coalition, a public interest nonprofit, said denying the public access to government records is a serious issue.

When agencies fail to turn over legally requested public records, "that means the system is breaking down, and you shouldn't have to sue the agencies. They should be producing records," Loy said. "Every time an agency loses a public records case means that it broke the law, and they shouldn't be breaking the law."

Reporter Damon Arthur welcomes story tips at 530-338-8834, by email at damon.arthur@redding.com, and on Twitter at @damonarthur_RS. Help local journalism thrive by subscribing today!

This article originally appeared on Redding Record Searchlight: Shasta County releases Ellis Report critical of sheriff's office