How Section 8 vouchers fail Sacramento’s unhoused. One woman has waited 14 years for housing.

The first time Kristi Phillips applied for a Sacramento Section 8 housing voucher, she was pregnant with her son Ty.

Now, Ty is 14. She’s still on the waiting list.

The family, which also includes two young daughters, has for years been living in hotel rooms, vehicles, and most recently a friend’s apartment. Last month they received an eviction notice.

Phillips sat on her couch in North Sacramento’s Northgate-Gardenland neighborhood on a recent weekday surrounded by boxes that they never live anywhere long enough to unpack. A list of backpack drives was taped to the wall in hot pink marker. A white sheet clung to the seat to the couch, where Phillips sleeps.

Phillips said waiting for a voucher so long is like living in a constant state of “false hope.”

“When I see paperwork in the mail from them I get so happy,” Phillips, 49, said. “But it just says it’s time to renew your information. I update the information every year. It’s so upsetting. I’m lost for words.”

Phillips is one of 51,000 Sacramentans who are on a waiting list for 13,000 Section 8 housing vouchers. In the last two decades, while the number of homeless people on the streets of the capital city has more than quadrupled, the federal government has given Sacramento only an additional 1,000 vouchers.

The housing choice voucher program, or Section 8, is a federal program administered by local housing authorities that provides funding through vouchers that are paid directly to landlords. The program is an essential tool in combating homelessness.

Or, at least, it could be.

A Sacramento Bee examination of the program and its consequences locally reveals myriad issues: Federal funding to provide more vouchers has remained stagnant despite the explosion of people who are unhoused.

▪ Like Phillips, many people wait years for their names to be chosen in a lottery that entitles them to a voucher.

▪ Those with vouchers often endure yet another wait because they must still find a landlord who accepts their voucher.

▪ Landlords complain that the cumbersome process can leave them waiting months for payments.

“It’s obscene to have to wait 14 years for a voucher,” said Bob Erlenbusch of the Sacramento Coalition to End Homelessness. “And when you get one it’s still no guarantee. The program is failing unhoused Sacramentans.”

Tamitha Myler’s experience illustrates the frustration and emotional toll exacted by the cumbersome process.

In a sense, Myler is one of the lucky ones. In 2019, she was selected for a voucher through the Sacramento Housing and Redevelopment Agency’s lottery program. She had been living in a city shelter that closed, leaving her back on the streets.

But the voucher turned out not to be the answer. She is now among the roughly 1,000 homeless people in Sacramento County who have a voucher but have not been able to find a landlord to accept it.

The housing authority has extended her voucher expiration date multiple times over the past four years.

Housing officials say the situation actually has improved. In January 2022, the list of people such as Myler who had vouchers but still no home was 1,250. Still, housing authorities acknowledge it takes an average of six months for voucher holders to actually find a place to live

So, for now, Myler waits. She’s living in a city-supplied trailer without air conditioning at the Camp Resolution Safe Ground in North Sacramento, working at 7-Eleven.

It’s illegal for landlords to reject tenants because they have Section 8 vouchers. But Sacramento voucher holders told The Bee that many in Sacramento continue to do so anyway.

“A lot of places say, ‘we don’t take that voucher,’” Myler said, sweat soaking her pink t-shirt as she sat in her trailer on a recent weekday gripping a Big Gulp of ice. “I don’t get it. They’re still gonna get their money either way.”

When someone has a voucher, SHRA pays the majority of the rent, and the person pays an amount they can afford.

Another Sacramento voucher holder, who The Bee has agreed not to identify because she is a survivor of domestic violence, said landlords have rejected her due to her credit score of 600.

She and her 15-year-old autistic son live in her Toyota Sienna minivan. She continues to submit applications, paying fees of up to $50 each time.

“(The landlords) know they’re not gonna rent to you, but what they’re doing is taking money from people who already are in a position where they are struggling,” said the woman, who is in a wheelchair. “They’re preying on the worst of the worst.”

Although landlords are guaranteed to receive most of the rent payment through the voucher, many still think the program attracts people more likely to damage the unit or cause problems, said Rayvn McCullough of the Black Parallel School Board nonprofit.

“There’s a stigma attached to people who have Section 8,” McCullough said. “There’s a bias against poor people. (Landlords) are contributing to the homeless population by leaving these properties open.”

Landlords, however, say they, too, are victims in the Section 8 program.

Chris Brown, vice president of Sacramento-based Project Management Inc., said landlords experience administrative issues with the vouchers on the part of SHRA. The agency, he said, owes him six months of rent for one tenant.

“The process to get the rent paid in full for the subsidy portions is almost impossible,” Brown said. “This program is very difficult even for experienced fee managers to navigate. I can only imagine what it’s like for private owners with smaller complexes or single family residences. The margins continue to decrease as the cost of doing business continues to increase.”

SHRA Executive Director La Shelle Dozier said that as long as the landlord has filled out all the necessary paperwork, including updates to it, there shouldn’t be a delay.

“We have thousands of landlords who participate in the program,” Dozier said. “Once that person is in the system those checks go out every single month.”

To incentivize landlords, SHRA launched a program that provided a one-time $2,500 bonus for landlords who took a Section 8 tenant in the last year. It also offered a $2,000 bonus for landlords who were returning as Section 8 landlords. They could also apply for damage claims, as well as funds to cover application fees and a security deposit assistance.

The incentive program added 128 new landlords. But funding ran out and SHRA recently ended the incentive – another blow to a program already beset by funding issues.

Congress not planning to add vouchers

Congress sets annual funding for vouchers. The House of Representatives and Senate must pass identical government spending measures — now stalled given that the House took the gavel from its former speaker, Rep. Kevin McCarthy. Figuring out who will lead the House comes first.

McCarthy, R-Bakersfield, was removed in part for winning bipartisan support on a short-term measure that kept federal agencies, including the Department of Housing and Urban Development, afloat through mid-November with 2023 appropriations levels.

The Republican-held House proposed funding the same amount of vouchers for 2024 while the Democrat-led Senate pushed minimal increases in July, the last time Congress made progress toward passing the spending bill for housing.

What they agree on now depends on a wide array of concessions for housing and other issues. Congress must pass, and the president must sign, next year’s funding allocations — or at least another short-term plan — by Nov. 17 to avoid a government shutdown.

Regardless of when spending bills pass, Sacramento’s voucher count wouldn’t change much, most likely not at all.

“Appropriations is always a challenge, especially in a divided government,” said Rep. David Valadao, R-Hanford, a member of the subcommittee that oversees spending for the agency in charge of housing programs, in July. “We still have work to do on these bills, and I’ll continue working with my House and Senate colleagues on both sides of the aisle to responsibly fund the government and keep Californians housed.”

Valadao’s office said in July that it was an accomplishment that the House’s spending proposal did not cut the number of vouchers: Inflation and the rising housing costs means keeping that number the same costs a lot more money.

Democrats were not satisfied with Republicans’ attempts to cap government spending.

“Despite the ongoing need for new resources, the Republican House majority is cutting vital programs that provide a lifeline for many families here in Sacramento,” Rep. Doris Matsui, D-Sacramento, said in a July statement. “I’m committed to pushing back against these cuts and preserving programs that help everyone live with dignity and security.”

Congress and the Biden administration have added more than 100,000 new vouchers nationwide since 2021, said HUD spokeswoman Shantae Goodloe. Of those, 1,000 went to Sacramento, according to SHRA.

But there’s a catch. The added vouchers are reserved specifically for specific populations, such as people with disabilities and military veterans. That means people such as Phillips and Myler are not eligible.

The last time Congress set significant funds for new vouchers was 2002, Will Fischer from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities said.

“Other than that, it’s been increases of small amounts,” Fischer said, “usually in the amount of a few thousand or $10,000 and usually targeted toward special populations like veterans and people with disabilities, and also some meant for replacing public housing that’s been demolished.”

Section 8 is one way the federal government can help ease the homelessness crisis. Another is for the direct support of public housing – housing that is controlled by public agencies and not private landlords.

But that, too, has been lacking.

Just this past year, Sacramento was poised to receive significant new dollars for affordable housing via the Build Back Better Act. But federal officials cut it at the last minute, Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg said.

“I call it the dark day,” Steinberg said during an August press conference. “Build Back Better had a lot of good things passed but no housing. That’s the kind of federal housing contribution we desperately need.”

The waiting lists to receive a public housing unit, as opposed to a voucher that can be used on the private rental market, is not much better.

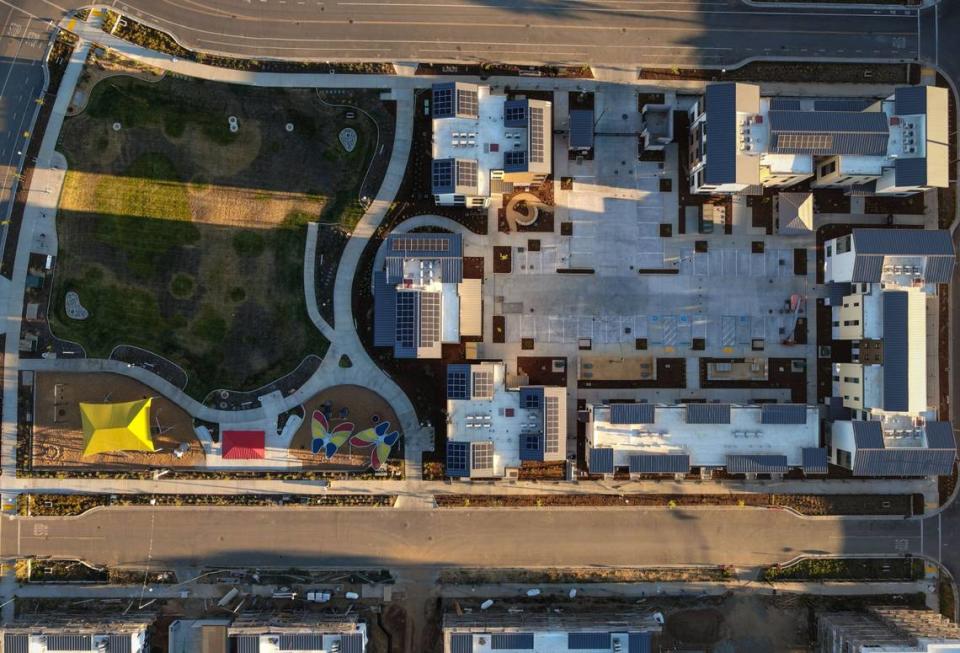

There are roughly 30,000 people currently on the waiting list. SHRA has recently redeveloped Mirasol Village in the River District. When it opened last year the wait list received 9,451 applications, including one from Phillips.

That’s 9,451 applicants for 300 spots.

Dozier said Sacramento needs a combination of vouchers and new public housing units.

Congress has not provided given SHRA money to build new affordable housing units since the late 1990s, Dozier said. It gives them just enough to renovate what they already have.

“We’re always looking to see what Congress is going to do,” Dozier said. “You have to live within the dollars they give you. In some years where they’ve cut back on that amount it can be very difficult. Every year we wait and see.”

But it’s not just Congress that has made building public housing more difficult.

In 2012, the state legislature put an end to local redevelopment programs. That was a blow because the special taxing districts created by redevelopment agencies were an ongoing funding source for housing authorities.

“In redevelopment we created a lot more (new units),” Dozier said. “I don’t think I’ll ever get done saying that. Under redevelopment we had (tax increment financing) that came to agency regardless of what the budget situation was.”

Before state lawmakers eliminated redevelopment, in 2012, Dozier said SHRA would receive $20 million a year just for its downtown, where thousands live on the streets. Now it gets at the most $6 million.

Lottery system

But if public housing is one option for the homeless, it is not always the preferred option. A Section 8 voucher gives more flexibility. It means living in a rental, in a neighborhood perhaps closer to work or school, and not a public housing project.

That’s one reason so many people take their chances with a lottery system that some believe is inherently unfair.

SHRA’s lottery system begins anew with each drawing. No special consideration is given to applicants whose names were not selected previously. That means a person who is applying for the first time could earn a voucher over someone who’s been trying for years.

Phillips disagrees with that strategy.

“I think they should do it by who’s been there the longest,” Phillips said. “I’ve been waiting so long.”

Dozier said that instead of giving preference to people waiting longest, they give preference to those who are homeless on the streets, as well as those with disabilities.

SHRA gives everyone a chance to apply for a Section 8 voucher, Dozier said in an email. Once the wait list is closed, a computerized random selection takes place, giving applicants points based on preferences, such as veterans and those with disabilities. Those with the highest number of points are considered first for a voucher.

“Those preferences have been established based on the need,” Dozier said. “If there’s too many preferences then there aren’t any.”

Dozier said nobody has technically been on the Section 8 waiting list more than four years, but Phillips says that in practice she has been.

Phillips’ name has never been drawn in the lottery, which are held every few years. Also, SHRA does not automatically enter the losers of the lottery to the next waiting list, spokeswoman Angela Jones said.

Phillips has been doing that on her own. As a result, when Phillips logs into her account today, it says she is still on the waiting list for a Section 8 voucher.

The wait can be excruciating – especially because of how much being selected and ultimately finding a home can change one’s life.

Jennie Welles lived on the streets for 23 years before her name was picked in the Section 8 lottery in 2020. Even then, her dream didn’t come true until this year when she finally found someone to accept the voucher.

“You forget that you have actual places to cook, lights, and air conditioning,” said Welles, 44, who lives in a downtown apartment. “The major difference is how people treat you. I am grateful for the opportunity to be inside so that I can give hope to other people that have been outside for so long.”

Phillips tries to keep the hope. It’s not easy.

She typically works, but it’s highly unlikely she will afford housing on the private market without a voucher to cover part of the rent. The typical rent for the Sacramento region is $2,300 – higher than Philadelphia, Denver and Dallas.

The high cost of living has driven the close-knit family to separate. While Phillips and Ty have been living in their friend’s house, her partner, Anthony, and their two daughters, 9 and 10, live in Anthony’s parents’ house down the street. Neither residence is large enough for the family of five.

Still, Phillips dreams of a day when the family live together in a home of their own.

“If we could get a voucher and find a landlord to take it, it would be life changing,” Phillips said. “The kids have never had their own rooms.”