See how five generations of family photos wound up in a Sacramento antique store

Jeanette Welch thought the photos may have been overlooked.

She and her husband, Craig Kletzing, had traveled to Carmichael from their home in Iowa to settle his mother’s estate. Ruth Kletzing died in November 2021 at 97. The couple needed to sift through the possessions accumulated over decades in the home where Craig had grown up.

They tried to make sure important objects went to close family friends, Welch said. And the couple returned to Iowa with a few keepsakes as well, such as photos of Craig playing music as a young man.

They had other concerns, though. Craig Kletzing was fighting the advance of a rare form of hereditary cancer that cost him one of his eyes as a child.

That’s how the photos from several generations of his family wound up at Schiff Estate Services, a Del Paso Boulevard store. These were photos capturing different points of family history that wound up for sale, generally for a few dollars apiece.

They also would point to a deeper story — one of where life takes us, the choices we make and the relationships we form.

How photos get to stores

It’s not uncommon for family photos to show up in antique stores. In fact, it happens frequently, according to Maureen Taylor, a historical photo expert based in Rhode Island.

“I have a closet full of photos I bought over the years,” Taylor said. “I mean, you go to any antique shop and you are going to find family photographs… It’s amazing the stuff that families don’t want.”

Taylor paid approximately $10 for a photo that appeared to date from the turn of the 20th century and had a family argument on the back. One set of handwriting said the photo was of their father, in front of a restaurant that he owned in Brooklyn. A competing inscription claimed it wasn’t their father and that he’d never been successful.

“I was like, ‘I’m not leaving this in the shop, I just can’t,’” said Taylor, who has blogged about the experience.

Margot Note, an archival consultant based in New York once bought a photo she thinks was taken sometime around the 1920s to 1940s with a Kodak Brownie camera. The photo was of three African-American people, one of whom appeared to be a bride.

What caught Note’s eye: A person in the background looking at the people being photographed.

“It was a very interesting kind of triangulation of people looking at each other in this photograph,” Note said.

There are signs of change with the internet, such as Old Photo Project, a Facebook group founded in 2016 to reunite family members with long-lost photos that has more than 23,000 members as of this writing. Taylor also noted a pandemic-era trend on TikTok of getting old photos back to family.

Taylor works with clients to try to help keep their photos from winding up in antique stores.

“I tell people to work on their photo mysteries, that a photograph with a name is less likely to be tossed than a photograph without a name,” Taylor said. “And the time to find someone to take your collection is while you’re still alive.”

Settling the estate

Following his mother’s death, Craig Kletzing sought out Schiff, which does estate sales and sometimes takes unsold items thereafter to its Del Paso Boulevard storefront.

Danyelle Petersen, the business’s co-owner, said they met with Craig and let him look through what he wanted from the estate.

“He was just saying, ‘Okay, I want a few things here and there,’” Petersen said, who also acted as the real estate agent to sell Ruth’s house. “It wasn’t much.”

Schiff organized a two-day estate sale at Ruth Kletzing’s home in April 2022 that grossed more than $50,000, according to Petersen. Highlights of the estate included mid-century modern furniture and prints from artists like Pablo Picasso and Alexander Calder.

But not everything sold.

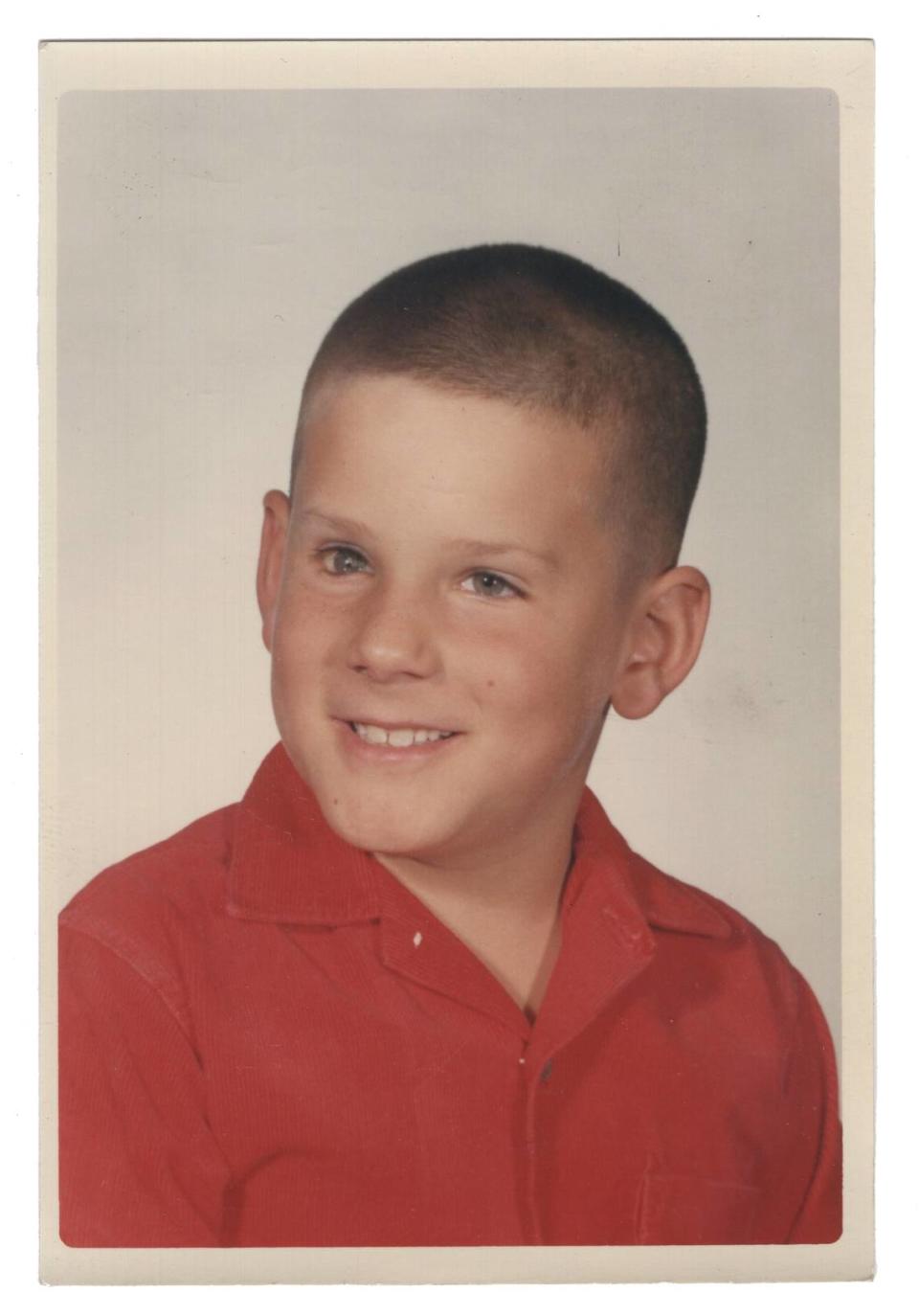

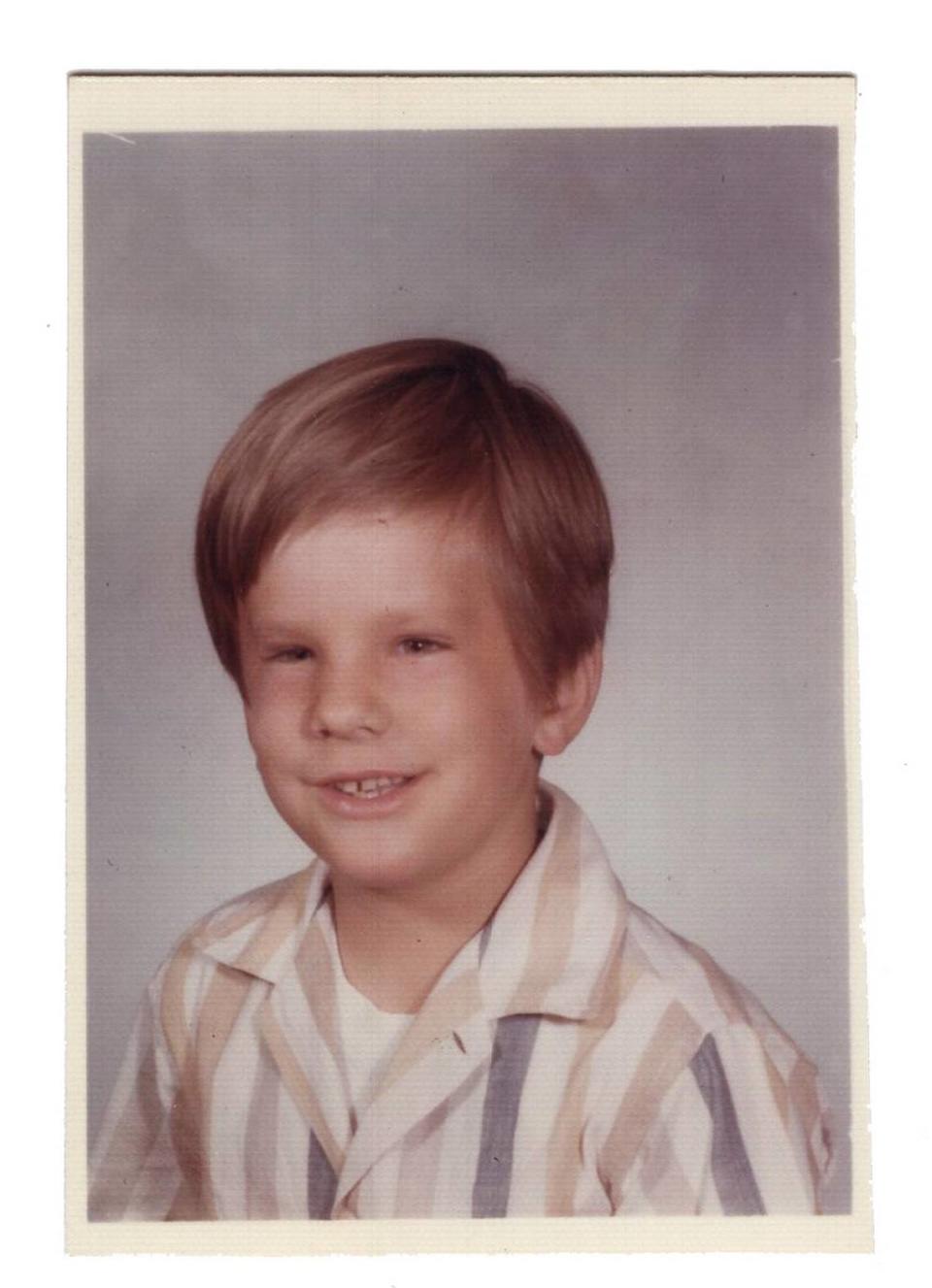

One of the things that wound up at Schiff was a school portrait of Craig from 1965, when he was in the second grade, with his full name written on the back. The photo was in a box with around 30 other photos.

A search with his distinctive surname on the websites Ancestry.com and FindaGrave.com revealed that the photos showed several generations of the maternal side of Craig’s family.

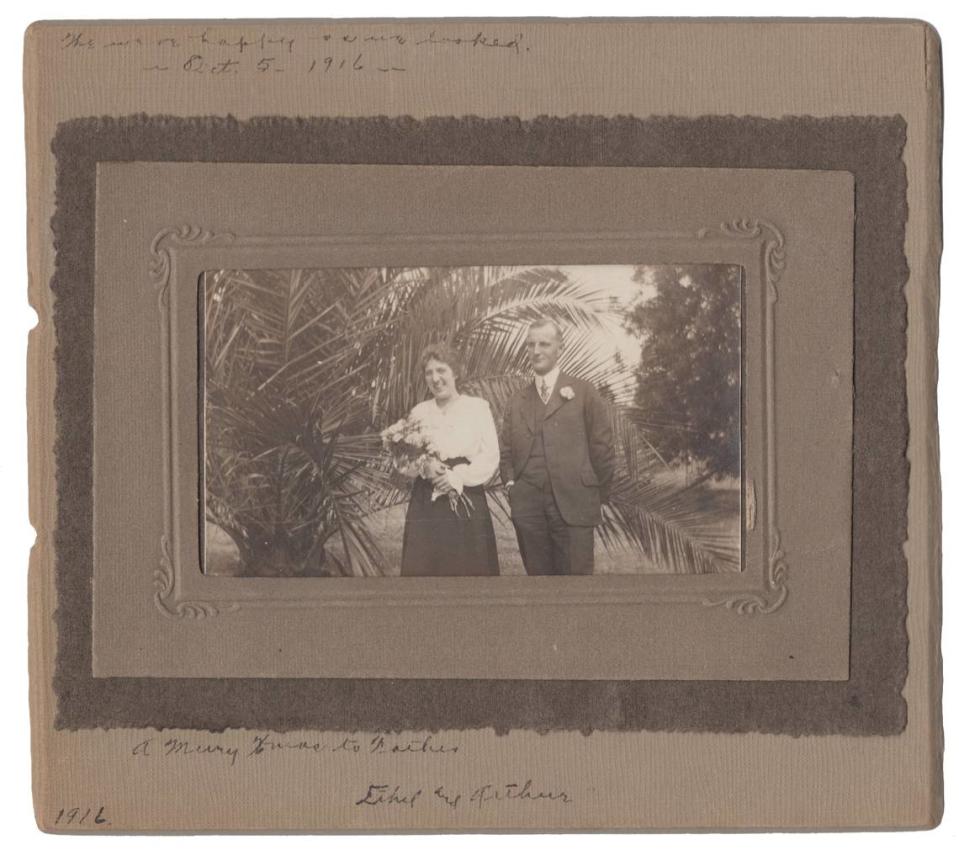

There was the October 1916 wedding photo of Craig’s grandparents, Arthur and Ethel Staples. There was a letter sent to Ethel that November in Oakland from J. Monroe Wolfe, pastor of a Methodist church in her native Ohio, granting her permission to transfer congregations.

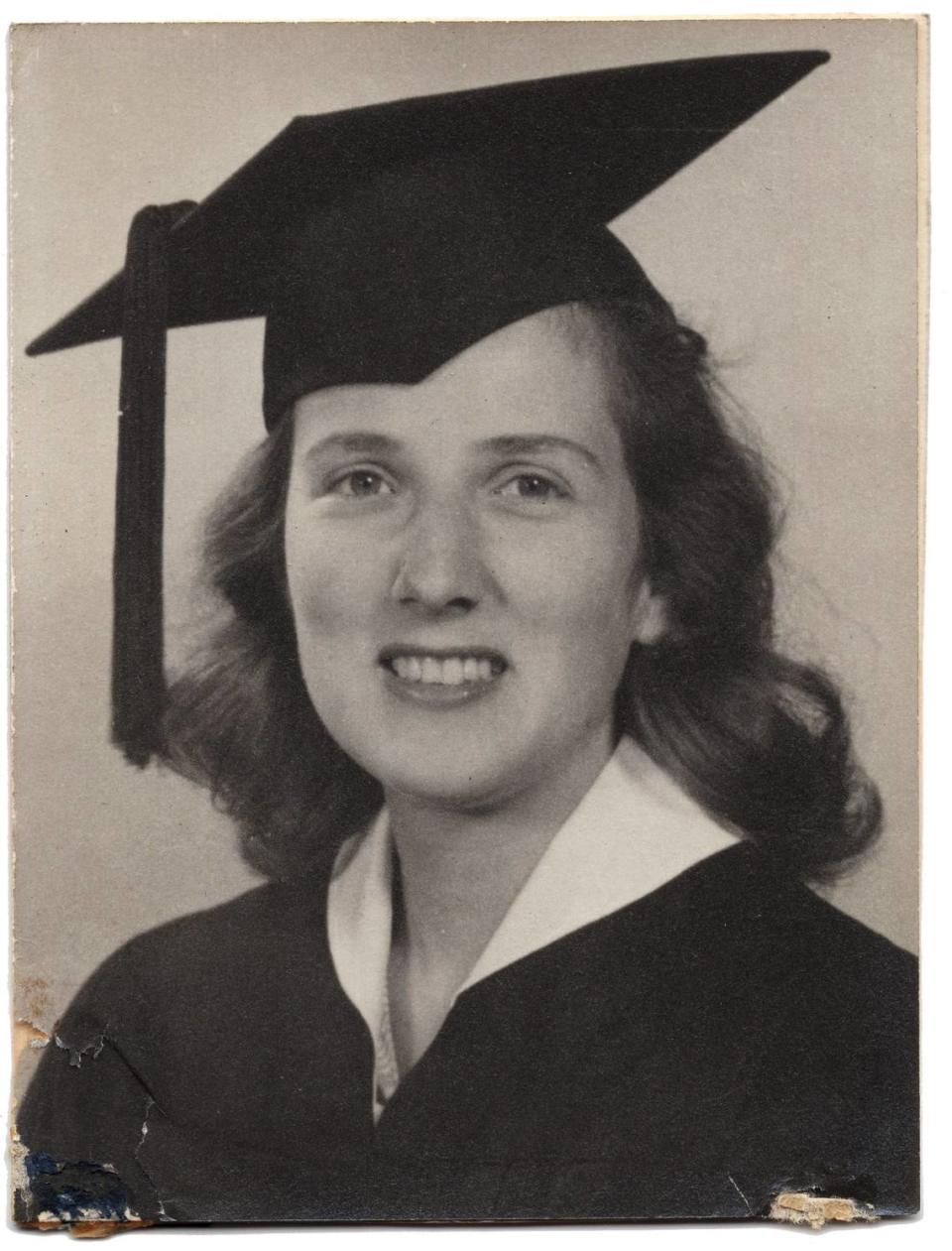

The Staples would raise two children, Ruth and Howard, remaining in Oakland until Arthur’s death at 76 in 1962. A framed photo of Ruth from the 1940s that wound up at Schiff captures her graduation from either high school or what is now the University of the Pacific. She later worked as a social worker and teacher at different points.

Photos from the 1960s show Howard with his mother after his father had died. There are also school portraits from the same era of Craig’s brother Jim and their cousin, Howard’s daughter, Nancy, who signed her photos to “Nana.”

The photos don’t span beyond the early 1970s, suggesting most, if not all belonged to Ethel, who died at 87 in 1974, and that they were passed on to Ruth.

The absence

There is at least one person whose absence from the photos found at Schiff is conspicuous: Craig’s father, Russell Kletzing.

Craig got the hereditary condition that led to his near-blindness from his father, and the men had other similarities. Each was highly intelligent, with Russell serving as president of the National Federation of the Blind from 1962-66 and also serving as a longtime attorney for the California Department of Water Resources.

Politically far to the left, Russell didn’t shy from fights. Julie Mandarino, who is now 75 and met Russell when she was 3 years old, remembered hearing one time about him being arrested after staging a sit-in at the California State Fair. The Sacramento Bee noted in 1968 that Russell hadn’t been allowed to use rides at the state fair and that the arrest was subsequently dropped.

“Russ’s life seemed to be about proving that he wasn’t handicapped, that blindness was not a handicap,” Mandarino said.

Harvey Swenson, 86, who moved next door to the Kletzings in 1970, remembered once giving a ride to Russell, possibly after he’d missed a bus he needed to get to work.

“So we’re driving downtown and Russ is fully blind, but he’s telling me where the buildings are,” Swenson said.

Not everyone appreciated Russell, though, such as his wife’s more politically conservative family. His niece Nancy Barr – the Nancy from the photos, Howard’s daughter – is now 71 and lives in Fresno.

“I don’t know if there was a family rift or whatever,” Barr said. “I know that my father and their father, Uncle Russ did not get along.”

It wasn’t just about the men disliking one another, Barr added.

“I remember my Aunt Ruth telling me that her parents did not want her to marry Uncle Russ because he was blind,” Barr said. “That was a lot of it, I think, and then even had my dad go talk, try to talk her out of marrying him.”

Chris Danielsen, a spokesman for the National Federation of the Blind said he was hopeful that blind people face less discrimination today from families they’d like to marry into, but that it’s hard to know for certain if this is so. In general, blind people still face a tough time finding acceptance in society.

“It’s better than it used to be – a lot better,” Danielsen said. “But we still have a 70%, roughly, unemployment rate. That’s seven-zero.”

Differences were seemingly never resolved between Howard and Russell, who died in 2010 and 2013, respectively. When Barr saw Craig at his father’s funeral, she thinks it might have been the first time she’d seen him since they were teenagers.

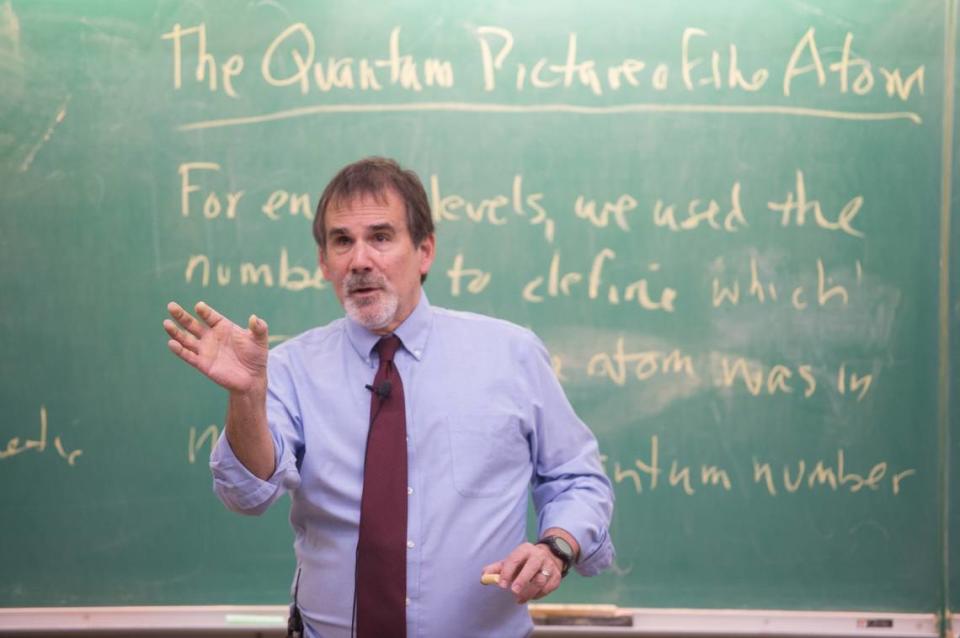

The physicist

Craig Kletzing’s life took him far from his childhood home.

After studying physics at UC Berkeley, he made his way to Southern California where two pivotal things happened: He earned his master’s and doctoral degrees in physics at UC San Diego; and he met Welch, who said she initially picked him up when he was hitchhiking in the early 1980s.

They started off as friends but became a couple within a few years. Opting to not have children, their life revolved around one another. They traveled the world and talked about retiring together in Hawaii. They played live music together, with Welch playing bass and Craig acoustic guitar in their band Truffle Pig.

Aside from his life with Welch, what Craig cared about was his work. He became a space plasma physicist, spending much of his career at the University of Iowa, a hub for space research.

In an article published shortly after Craig’s death, a university spokesman wrote that Craig had been involved in 30 space or near-Earth missions in his time at Iowa and that he’d secured a $115 million contract from NASA in 2019 for the TRACERS mission. It was the largest research grant the university had ever received.

Colleagues like Allison Jaynes, who met him when she was a graduate student and was eventually hired by him as an associate professor at Iowa, counted him as a mentor.

“He was working on multiple NASA projects all the time and had students in a big research group, so you knew that he was busy,” Jaynes said. “But yet, he would take the time to talk to someone who was just starting out or a junior person. And like sometimes, he would take hours to talk to you.”

While Craig was fully engaged with those in his academic world, his contact with those from his California childhood was driven by happenstance and the deaths of other family members.

Mandarino, who also moved to Iowa, had limited contact with Craig despite living nearby. She did keep in contact with Ruth Kletzing and therefore stayed abreast of Craig’s and his brother Jim’s lives.

After Ruth died, Mandarino received $5,000 from her estate. Craig and his wife also sent her a wooden lamp that Mandarino remembered from the Kletzing family home when she was young.

She didn’t know what had transpired since. And she wasn’t the only one in the dark.

Preserving the link

With a daughter who lives in the Sacramento area, it wasn’t hard for Barr to keep in contact with Ruth Kletzing. She adored her aunt and continued to make trips to see her even as Ruth’s health began to fail and the pandemic shifted visits outdoors.

The health of other family members was beginning to fail around this time, too. Ruth’s son and Craig’s younger brother Jim, who also had hereditary sight issues, died of saurcoma around 2020.

Barr and Ruth had their final visit at Thanksgiving in 2021. Barr got a subsequent call from Craig where he shared news of Ruth’s death. She asked to be notified if there was a funeral for Ruth but never heard back. She’d been unaware, before being contacted for this story, of Craig’s death in August from his cancer at 65.

“That’s the last of my family,” said Barr, emotion clear in her voice.

A day later, Barr was interviewed at length for this story via Zoom, explaining about the gulf between her uncles, but also laughing and telling stories of the people connected to the photos.

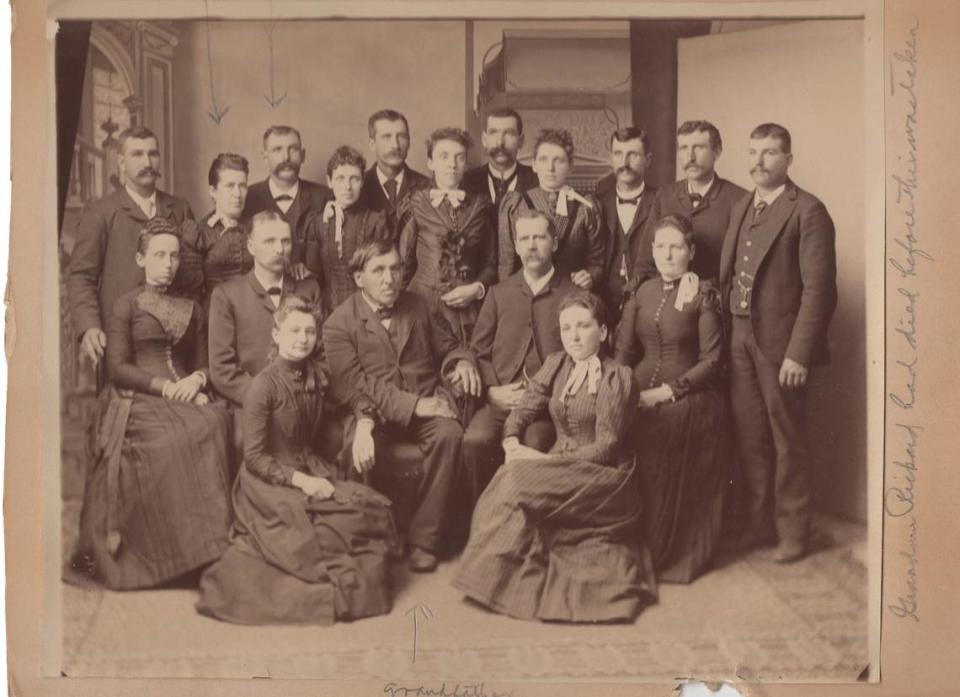

She also told a story related to what appeared to be the oldest photo in the group.

The photo looks like it was taken in the late 19th century, showing 18 people with serious expressions and dark clothing, like they might have been gathered for a funeral.

The original owner of the photograph, or someone with knowledge of the people, used the cardstock upon which the photo was mounted to scrawl “father’s family the Rickards.” Pencil-drawn lines point to a grandfather, a mother and a father.

The photo is of Barr’s great-great-grandfather, Daniel Rickard, an Ohio farmer who died in 1904 and his family. (Spellings of the family name varied, with Rickert on his grave headstone.) The penciled lines point to Ethel’s parents, David and Adelaide Rickard.

Barr has a granddaughter named Adelaide. After her granddaughter was born, Barr shared the news on Facebook.

“Aunt Ruth immediately responds back and said, ‘I bet you didn’t know that Adelaide is my middle name. And it was your great-grandmother’s name,’” Barr said.

Barr said her daughter came up with the name Adelaide, close to delivery, after she’d had a dream that involved a little girl with the name. Neither of them had been aware of the family significance of the name.

“Seeing all those photos brings back lots of wonderful memories,” said Barr, who is being sent digital copies of the photos. The originals are being sent to Welch, who requested them back.

As for Taylor, she knows what she’d say to someone thinking about buying an old photo from an antique shop.

“I’d say buy them and find the story,” Taylor said. “Because the story for some of these photographs is better than any novel you’ll ever read.”