See you in the funny papers: Comic strips' evolution as a uniquely American art form

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As the USA TODAY Network debuts a new comics lineup across the nation, we are delving into the history and cultural impact of this uniquely American art form with experts from Ohio State University and the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum, the largest collection of comics in the nation.

“Comics and cartooning (have) been around for a long time, but something special happened with the combination of comic strips and newspaper,” said Jared Gardner, the Joseph V. Denney Designated Professor of English and director of popular culture studies at OSU.

“In the first half of the 19th century, newspapers had been around for centuries but had very few images because images had to be engraved or etched. By the second half of the century, they were becoming more visual."

Here, Gardner and Jenny Robb, head curator of the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum, touch on some watershed moments in the vast history of comic strips and their place in American culture.

Joseph Pulitzer, the New York World and the birth of comic strips

Joseph Pulitzer's sensationalistic New York World was one of the first newspapers to publish comic strips, beginning around 1890. Many noteworthy comic strips were born in the World, including Ohio-born Richard F. Outcault's "Hogan's Alley," considered the first commercially successful newspaper comic strip.

When the strip began in 1895, readers quickly honed in on one character in particular: the Yellow Kid, a jug-eared urchin in a yellow nightshirt, his head shaved to prevent lice, who is widely credited as the character who gave birth to American comic strips.

"(Outcault) created these big scenes of these street kids making fun of things rich people would do. It was chaotic, with lots of humor and lots of slapstick," Robb said.

Drawn by Outcault in the World from 1895 to 1896 in a series of large, single-panel color (more on color comics later) illustrations, the Yellow Kid was a hit with readers.

"(The Yellow Kid) became so popular and sold (so many) newspapers that they merchandised him — not just toys for kids, but cigarettes and alcohol. He was just a powerhouse of merchandising."

Comical cancellation: 'Mallard Fillmore' and the comical side of cancel culture. 'Doonesbury' has already been there.

Gardner echoed Robb's depiction of the Yellow Kid as a boon to newspaper circulation.

"The Yellow Kid brought readers to newspapers," said the comics aficionado. "Readers would fall in love and want to find out what happened next."

As it turned out, the Yellow Kid also was popular with Pulitzer's rival, William Randolph Hearst, who poached the World's staff, including Outcault, to work for his publication, the New York Journal.

"When Richard Outcault was stolen by Hearst, George Luks started drawing (the Yellow Kid) for Pulitzer, so they had dueling Yellow Kids," Robb said. The two versions of the Yellow Kid competed for more than a year.

It was in the Journal that Outcault detoured from the single-panel format and drew his signature character in a series of panels on Oct. 25, 1896.

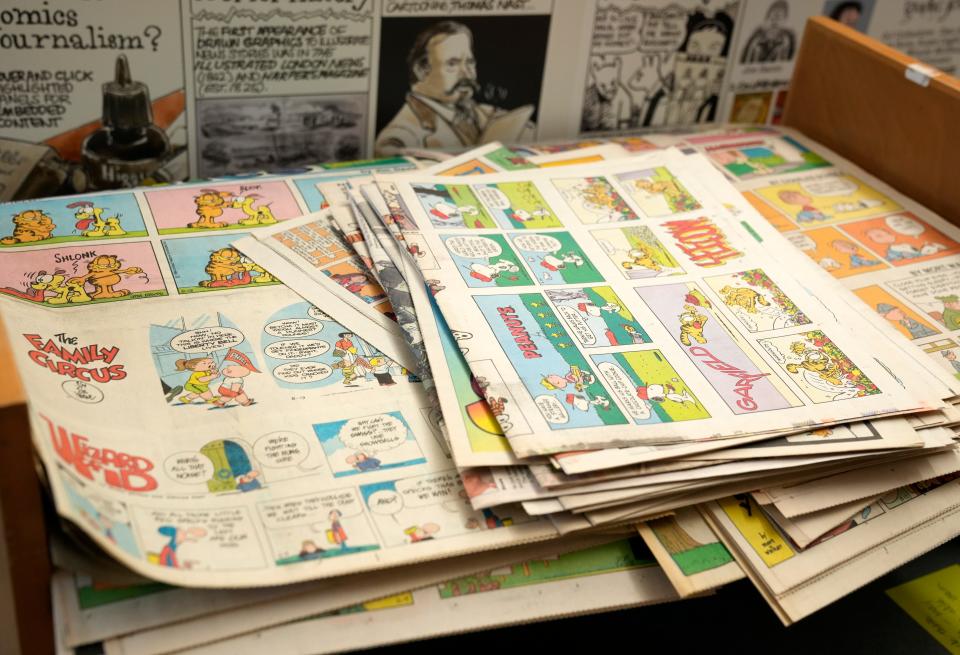

The 88 Yellow Kid tear sheets in the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum's digital album are part of an enormous collection of comic strips, Sunday features and other print materials from the 1890s to 1990s acquired by OSU from the San Francisco Academy of Comic Art in 1997.

Sunday becomes colorful as comics make newspapers collectable

Robb said that newspapers had been publishing proto-comic strips and editorial cartoons starting in the 1880s, but on Nov. 18, 1894, a radical change in appearance — and a leap in sales — came when the first Sunday color comic section was published in the New York World.

"It just took off because it was just so popular. People loved them," she said, adding that the advent of color only fueled the battle between Pulitzer and Hearst.

"They were trying to expand daily papers as something the masses could afford and competing for readers, so comics were this colorful type of storytelling that helped them sell newspapers."

'Dilbert' dropped: USA TODAY Network, newspapers and distributor drop Dilbert comic after creator's racist comments

Sunday color supplements upped the ante for smaller publications as well, Gardner said.

"In those days, even small cities had multiple newspapers and the Sunday supplement became a big part of the competition," he said.

Prior to color publishing, old papers were used for "fish-wrap or thrown away," Gardner said. But the new, brightly hued newsprint allowed publishers to "create something unique."

"The Sunday supplement became something to keep around for the week. It had a lot of stuff for kids and family-friendly strips," he said. "It was a chance to create a new part of popular culture. That never existed before."

The plots thicken as comics go daily

When cartoonist Bud Fisher conceived an idea for a horizontal comic strip, his editor at the San Francisco Chronicle nixed the proposal, saying it would take up too much space. But Fisher was dogged in his pursuit, leading to the creation of "A. Mutt" (the "A" stood for Augustus) in 1907.

"He came up with this idea of Mutt betting on a horse every day, then people could find out the next day if Mutt's bet came in," Gardner said. "It's another thing when you're living with a character every day."

In 1908, Mutt met Jeff, an inmate from a mental health hospital who would change both his life and the comic strip bearing his name. "Mutt & Jeff became the first successful daily comic strip," Gardner said.

"It was so popular that William Randolph Hearst, the grandfather of newspaper comics, didn't just see it as a business proposition; he loved comics. He said (to Fisher), 'We're going to syndicate you.'

Farewell to 'Funky': Cartoonist Tom Batiuk says goodbye to ‘Winkerbean’ comic strip

"Suddenly, there are newspaper syndicates — the Hearst Syndicate, the King (Features) Syndicate. Comics could be published across the country and every day on the same day, everybody would read the same comics. This became, really, the first national water cooler talk!"

Daily comics gave characters the freedom to engage in ongoing adventures, as was the case with strips like Harold Gray's "Little Orphan Annie" and "Terry and the Pirates" by Milton Caniff, who attended OSU and worked under cartoonist Billy Ireland. And with these continuing storylines came emotional investment by readers.

The Chicago Tribute Syndicate’s first daily strip in 1917, “The Gumps,” about an ordinary middle-class family, is a favorite of Gardner’s and a perfect example of how readers came to hold certain characters as beloved. When creator Sidney Smith became the first cartoonist to kill off a character named Mary Gold in 1927, the national outcry was instant.

"He got so much mail — effectively, hate mail. Newspapers started getting letters asking about the funeral and where they could send flowers. People were mourning this character," Gardner said.

Comic strips break the color barrier amid the civil rights movement

Prior to the civil rights era, comic strips featured few Black characters aside from offensive caricatures and stereotypes — and even fewer Black artists.

“(Comics) was an incredibly segregated medium,” Gardner said. “So, African Americans began to set up their own newspapers with their own cartoonists and their own stories because no one was writing stories about what was happening in the African American community.”

Still, the world of mainstream comics remained largely white. As the fight for racial equality intensified, Black cartoonist Morrie Turner began questioning the lack of people of color in the comics. His friend and mentor, Peanuts creator Charles M. Schulz told him, “You should do a strip,” according to Robb.

Turner’s first effort, the all-Black “Dinky Fellas,” was unsuccessful, finding a home in one Black newspaper. Rechristening the strip “Wee Pals,” Turner drew a group of friends from diverse ethnic backgrounds and physical capabilities, and it became the first syndicated strip of its kind.

Still streaming: Video and Q&A: Bill Watterson discusses 'Calvin and Hobbes' doc

Initially, only five papers would agree to carry a comic with Black characters. That changed with the April 4, 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., when “Wee Pals” was picked up by more than 100 papers. “He lamented the fact that it took (King's death) to get more widely syndicated,” Robb said.

That summer, Schulz would go on to introduce a Black character into his own comic strip. According to the Charles M. Schulz Museum website, Schulz was moved to create Franklin Armstrong after corresponding with Harriet Glickman, a Los Angeles teacher, who believed that Peanuts could positively influence attitudes on race.

"Schulz showed Franklin and Charlie Brown meeting on the beach at a time when beaches were segregated. And then they all went to the movie theater, when movie theaters also were segregated," Robb noted.

"Schulz was sending a message. A lot of papers were uncomfortable in the South, but he stood his ground. It's an important moment."

Gardner reinforced Robb's assessment. "Franklin becomes one of the gang," he said. "It was a big deal at the time for readers coming from a minoritized community seeing themselves not being played for comedy."

Comics and 'cancel culture'

From time to time, a comic strip creator will cause such outrage that newspapers will drop the strip altogether, as was the case with "Dilbert" artist Scott Adams earlier this year.

Numerous papers, as well as the USA TODAY Network and the strip's distributor, Andrews McMeel Universal, severed ties with Adams after remarks he made on his online video show describing Black people as part of a "hate group" that white people should "get away" from.

Other strips have been the target of ire, most notably Garry Trudeau's "Doonesbury," which has been withheld or given the boot altogether a handful of times in its 50-plus years of existence.

"When (Trudeau) declared the Watergate conspirators to be 'guilty, guilty, guilty,' a lot of papers were upset," Robb said of the 1973 strip that was pulled by The Washington Post, Boston Globe and other newspapers.

"I felt great sadness when 'Doonesbury' got expelled from the comics page and put in editorial — it was isolated and disconnected from the rest of the paper," Gardner said.

"Newspaper comics can’t exist isolated from the rest of the paper, from the events and news of the world. 'Doonesbury was really part of why I got interested in newspaper comics and a kid. It made me want to read the rest of the paper."

Also, Gardner said, "Doonesbury" transcended liberal vs. conservative in terms of its readership. "Trudeau was left of center but had readers of all views; they would engage in political conversations. That's missing today.

"It wasn't about either right or wrong opinions, it was about people debating about things, sometimes disagreeing but trying to listen. I can't think of any medium better positioned to help teach us how to be a community again, a community that is united in our differences."

Early LGBTQ+ representation

In the early 20th century, the comic strip "Lucy and Sophie Say Goodbye" walked so contemporary artists like Alison Bechdel and Lynn Johnston could run.

The 1905 Chicago Tribune strip, whose artist remains unconfirmed (some believe it to be Robert J. Campbell, creator of the Tribune's "The Career of Cholly Cashcaller"), centered on the hilariously drawn-out goodbyes between the title characters.

Lucy and Sophie's farewells, which always held up urgent business bustling around them, initially included a kiss obscured by their Belle Époque-style hats. But as the strip continued, their kisses and embraces became less ambiguous and decidedly more passionate.

This anonymously created comic strip help lay the groundwork for Bechdel's diverse cast of mostly queer characters and Johnston's four-week arc in "For Better or For Worse" chronicling the coming out of teenage character Lawrence in 1993.

"It felt right for Lawrence to be gay," Johnston says on the "For Better or For Worse" website. "He was like so many people I know who have had to deal with this traumatic realization and who have done so with courage and honesty."

"Newspapers received a lot of support letters, but also a lot of hate mail. A lot of papers wouldn't run (Johnston's strips); a lot of people weren't ready to accept it," Robb said.

"It was told in such sensitive and thoughtful way. At the time, that was really a brave thing to do in the comics page. Many people thought comics should just be funny, but (Johnston) said she also wanted to tell real stories."

Nearly 120 years later, "Lucy and Sophie" lives on in the annals of comic history and fame as an early example of a same-sex relationship.

Comic strips in the contemporary world

As more people turn to the internet for their news, the same is happening with comic strips, especially among younger generations, Gardner said.

Relating a story in which his students didn't realize "Calvin & Hobbes" was a newspaper comic strip, Gardner said, "There's a misguided sense that young people don't read comic strips, but they do — online," he said.

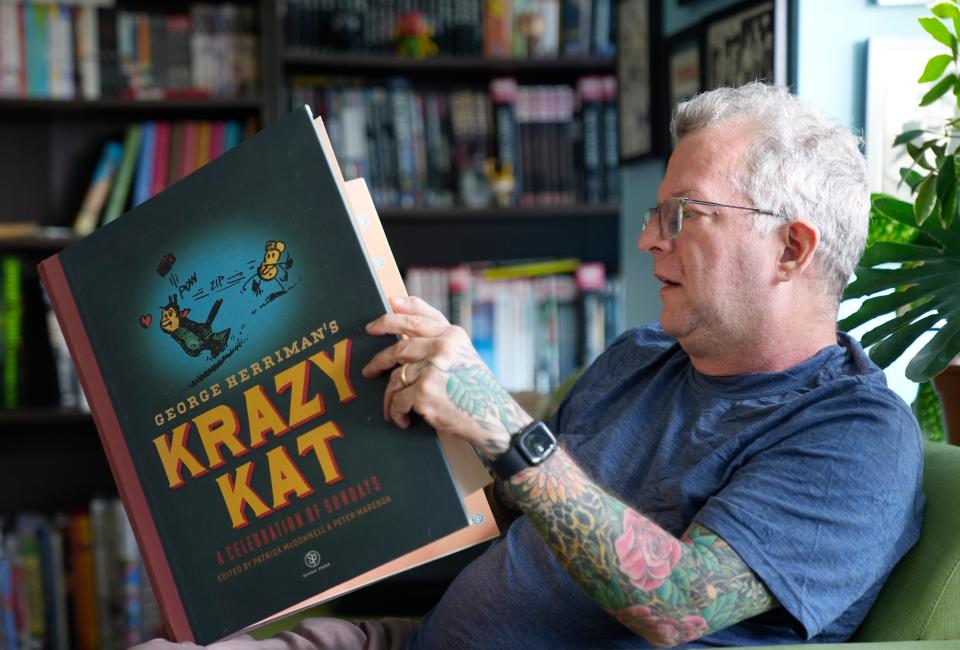

Technology also is shaping how comic strip artists create, Robb said.

“In the last 20 years, we’ve been seeing many artists move entirely to digital art. There’s no originals; it’s all bits and bytes,” she said. “The style of art has also changed dramatically over the decades as cartoonists are looking at what’s going on in other popular arts and reflecting that.”

In addition to being "entertaining and fun," Robb said comic strips both inform readers and are informed by current events. "Comics have definitely reflected what was going on in the culture of the time. You could see what people were thinking about, concerned about and laughing at by looking at the comics," she said.

"When they were created, they were really at the crossroads of popular art and entertainment for the masses. People were thinking of them as just for kids or a way to sell newspapers. (Comic strips) didn’t have the same respect as other art forms. But it’s an art form in itself."

Gardner agreed: "The form is relevant … the form has life."

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Comic strips' history and impact on American culture still relevant