After seeing his homeland of Zimbabwe struggle, he opened a Charlotte gallery to help

A University City shopping center that’s home to a FedEx print shop, IHOP and Qdoba may be an unlikely place for an art gallery, but this isn’t a conventional gallery. It’s a way for Calstain Ganda to support people back in his native Zimbabwe.

“The truth is,” Ganda said, “the pandemic opened this gallery.”

Ganda, who goes by Cal, is talking about the two-story, 2,000-square-foot Real African Art Gallery in McCullough Commons across Harris Boulevard from UNC Charlotte, which he opened in February. Ganda, who moved to the U.S. in the late 1990s for college, now works full-time as an executive for an automotive aftermarket subsidiary.

“I had no plans to open a gallery,” Ganda said. “I was doing shows on the weekends. I had a little at-home gallery. But when I went home to Zimbabwe last August, I have never in my life seen that country on its knees the way I did. It broke my heart to pieces.”

Zimbabwe, the landlocked country formerly known as Rhodesia, is between Botswana and Mozambique. It’s also a country known for its stone sculptures.

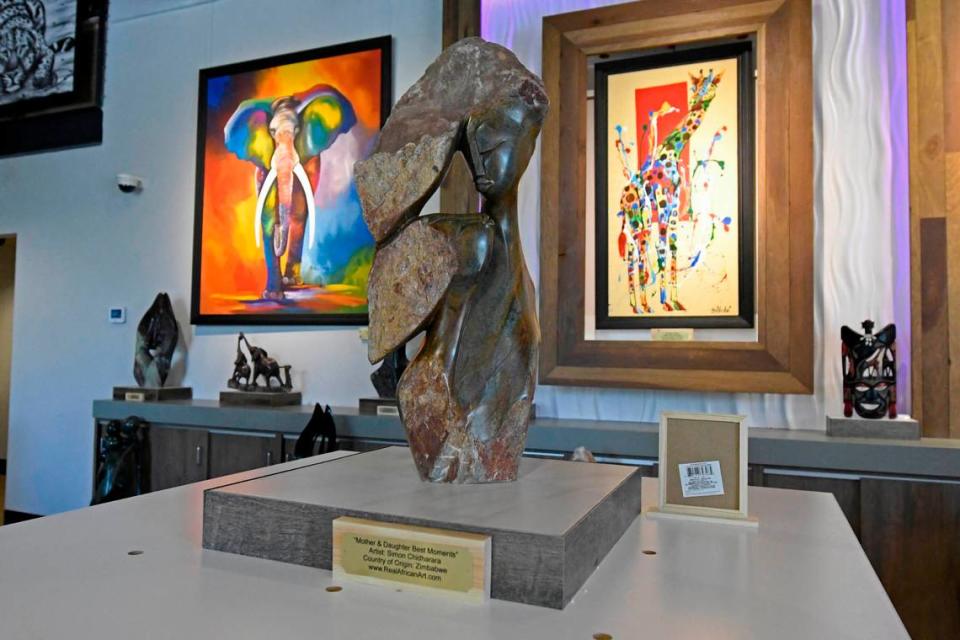

“Stone sculptures are the cornerstone of my gallery,” Ganda said. “Zimbabwe has the best stone sculptors in the entire world.”

In pre-COVID times, tourists bought them as souvenirs. But tourists stopped coming last year.

“Look where (Zimbabwe is) right now,” Ganda said. “No one comes to this place. No one to sell to. No jobs.” Tourism is an important part of the economy in a country that’s experienced economic decline since former prime minister and president Robert Mugabe’s authoritarian rule.

A village hero

Ganda came to the United States for college in 1998 and has lived here ever since. He’ll tell you repeatedly how blessed he’s been and how his late mother shared the money he sent home with her neighbors.

It seemed natural to make “small loans” to the sculptors back home, $100 here, $200 there. “People began to pay their bills, feed their families,” Ganda said. Word spread, and soon everyone wanted a loan.

“I don’t have enough to loan my whole village,” he said.

So he decided to put them back to work. “Soon, yours truly has inventory that wasn’t really planned,” Ganda said. With three full storage units containing $80,000 worth of art, he needed another plan and a bigger venue.

‘Coming to America’

Ganda’s story, which he calls “my coming-to-America story,” is as improbable as his gallery.

He said his aunt and uncle, Ruth and Robert Thornton, are the reason why he is here in the U.S. “My aunt married a white man from Texas in the ‘70s. It is through them that I received my opportunity to leave Africa and have a chance to come to school here.”

It was 1998, and the Thorntons’ son, Robert Jr., was headed to Davidson College, his father’s alma mater. The Thorntons suggested Ganda look at North Carolina colleges, too.

Ganda’s response: “It’s America. Just sign me up!” He sent out applications, and UNC Pembroke was the first to respond.

The future gallery owner, who majored in business, graduated in fewer than three years. And he went immediately to work.

With a full-time job as head of the Americas automotive aftermarket division at Continental, Ganda can’t manage a gallery, too. So he hired Trey Bailey, a college friend, as his manager. A nephew also works part-time in the gallery and Ganda’s 16-year-old daughter works there up to 12 hours a week.

Everything in the gallery is handmade, he said. There are paintings and ceramics in addition to the stone work.

Except for a small section of work by unknown craftspeople he buys from a Cape Town market, he can tell you the name of the artist of every work in the gallery. He probably even knows them.

Sharing the wealth

He seems amazed by his success.

“The vast majority of Africans are living in poverty,” Ganda said. “It’s a tough life. Half the time, there is no running water. Certain parts of the country receive power from 8 a.m. to 2 p.m., others from 2 p.m. to 8 a.m. Last year, I was back home from Aug. 18 to Sept. 12, and there was not one day when I had 24 hours of running water and electricity.”

Had Ganda remained in Zimbabwe, he may have become a stone sculptor himself: “When I was growing up, this was part of what we did every day.”

Zimbabwe, he said, “literally means ‘houses of stone.’ “

The Shona, an ethnic group native to southern Africa, have been stone workers since the 11th century. Family and nature are the most common themes explored in Shona art.

“If you’re a young Zimbabwean male, you know stone sculpting is in our blood,” he said. “You pick up a piece of stone with nice coloration, and it’s inevitable. You are going to get a hammer and a chisel.”

There’s no formal training. “Nobody is going to say, ‘Sit down, son, and get to work,’ ” he said. “Your own inquisitiveness drives you. Then, the established artists will say, ‘Great, young man. So, you want to be in the craft? I have finished this piece right here. Polish it for me.’ This is how most of the guys get started. You prove your worth.”

It’s tedious and physically demanding, Ganda said, and nearly all stone sculptors are men.

Ganda is as interested in getting Zimbabwean sculpture into people’s homes as he is in helping the sculptors back in Africa. The pieces start at about $20 and goes up to $5,000. The average price is around $100 to $125.

He’s had customers feel drawn to a piece they can’t afford to buy on the spot. He’ll allow them to make a down payment and pay in installments.

The gallery isn’t a way for Ganda to enrich himself. He simply wants the people back home to earn a living.

“This is not what a poor African child was supposed to accomplish,” he said. “But God has been gracious, and that comes with responsibility.”

African Art

What: Real African Art Gallery

Where: 440 E. McCullough Dr. Suite A-111, Charlotte.

Learn more: realafricanart.com or follow the gallery on Facebook at facebook.com/realafricanart.

This story is part of an Observer underwriting project with the Thrive Campaign for the Arts, supporting arts journalism in Charlotte.

More arts coverage

Want to see more stories like this? You can join our Facebook group, “Inside Charlotte Arts,” at https://www.facebook.com/groups/insidecharlottearts/