SEIDMAN SAYS: Curtailing children’s access to books could have lifelong impact

My third grade teacher, Miss O’Bern, was a stern taskmaster. She ran the academic day like a drill sergeant, brooked no dissent and accepted no excuses. Both her tone and the ruler she carried in one hand were sharp and intimidating.

In those pre-politically correct days, we called her a spinster – never married, no children – but by god, she was determined to leave her mark on any student who entered her classroom. As a meek, shy and anxious child a year younger than most of my classmates, she frankly scared the bejesus out of me.

Yet I loved that year, and this is why: When you finished your work with time to spare, when you did an excellent job on your report, when snow or rain precluded going outside for recess or you just needed a little time away from the fray, Miss O’Bern would excuse you to the reading corner. How I lived for those moments!

There, you could select any volume you wanted from shelves packed not only with the popular favorites – Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys and Trixie Beldon – but untold literary treasures, including some that would likely be considered too “mature” or subversive by today’s standards. Then you’d curl up in a bean bag chair next to the clanking radiator and lose yourself in the pages.

The long, wide bookshelf at one end of her classroom was a reward, a beacon, a refuge. For me, it sealed a love affair with reading that endures to this day.

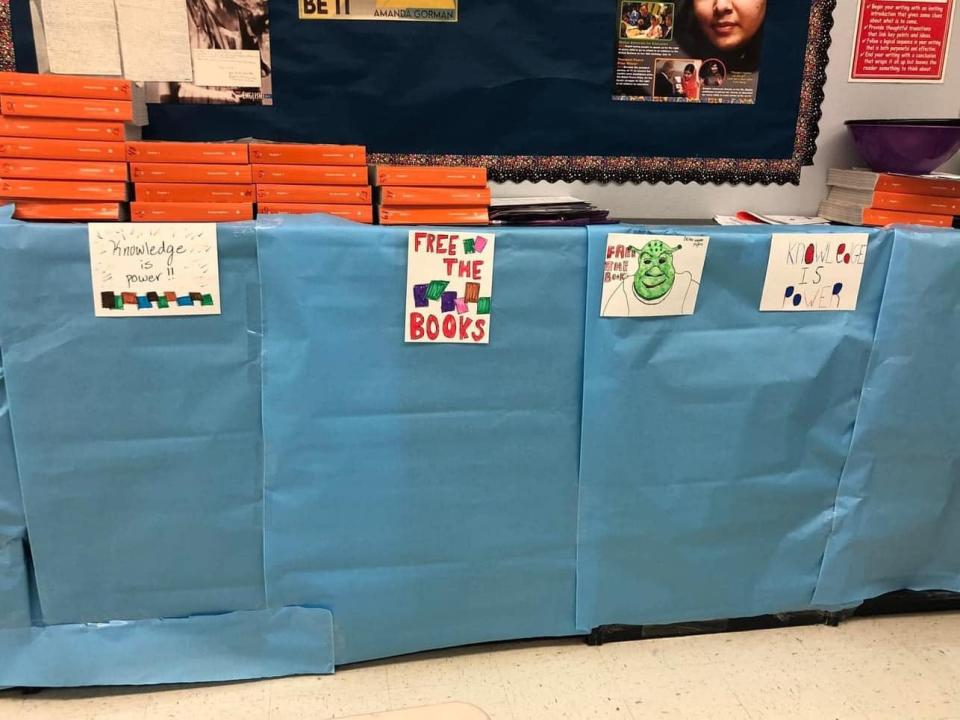

Which is why I nearly cried when I read the Herald-Tribune's story about the Manatee County School District advising teachers to remove or cover up classroom libraries to comply with a new Florida law. HB1467 requires all school books be vetted by a media specialist for pornography, indoctrination or anything deemed “inappropriate for age level or group” and warns that teachers found with such materials in the classroom could face third-degree felony charges.

Administrators said their motivation was to protect the teachers, but did anyone consider the effect on students? The lack of access to books at a time when we should be cultivating a lifelong habit of reading for pleasure seems like a surefire way to produce a more uninformed and ignorant citizenry.

Already a National Assessment of Education Progress study has shown that children who say they spend time – any time at all – reading “for fun” has dropped to the lowest level in four decades. How might my entire life have been different if that love of reading hadn’t been instilled in my formative years?

My earliest memories are of my mother reading bedtime stories, using a different inflection for each character’s voice. Later, my siblings and I read on our own, often insatiably, with a flashlight under the covers after “lights out.”

When school let out for the summer and we moved to our cottage on Lake Michigan, the first thing we did was sign up for the summer reading program at the local library. Since you could only check out five books at once, you not only read your own picks but the more mature choices of your older siblings as well. That’s how I came to read “The Diary of Anne Frank” at 8 years old.

Nobody “vetted” what we read and we were indiscriminate consumers – everything from beach reads left behind by summer guests to my brother’s MAD magazines. When we swiped the babysitter’s copy of Jacqueline Susann’s bestseller, “Valley of the Dolls,” my mother didn’t take it away, but simply asked if I understood what “dolls” were (barbiturates, and no, I didn’t). She seemed unconcerned that, under its influence, I would become a drug addict or try to sleep my way to the top of the entertainment industry. (To date, I have done neither.)

When I was a directionless college freshman forced to choose a major, I picked English, not because I wanted to teach or even to write, but because the book syllabus looked so enticing. Reading “All the President’s Men” planted the first seed for a possible career in journalism, a career now in its fifth decade.

I panicked when my young son, struggling with learning disabilities, did not show the same interest in reading, despite my force feeding of children’s classics. A wise teacher suggested I “let him read whatever he wants” and, for a long time, that was comic books and the Goosebumps’ horror series. Today, unlike many of his peers, he spends almost as much time reading books as he does on the internet.

My mother had a subscription to the New Yorker her whole adult life; years after the debilitating stroke that left her disabled and without speech, its weekly arrival sustained her. She laughed and nodded when I joked that life wouldn’t be worth living if you couldn’t read the New Yorker. One day I noticed she’d been on the same page for a week. Not long after that, she died.

All of which is to say that a love of reading is a lifelong gift. It has given me much more than a healthy vocabulary and a long career. Books have been my friends when I thought I had none, given solace in times of grief, helped me navigate both relationships and foreign countries and introduced me to worlds far beyond my own. Sometimes when I’m in the library, I feel the way I do standing on the edge of the ocean – small, with so much more to learn.

A bookshelf covered in construction paper – or worse still, empty – sends an entirely different message.

Contact columnist Carrie Seidman at carrie.seidman@gmail.com or 505-238-0392.

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: Carrie Seidman: Blocking access to books could affect children