Sen. Jon Ossoff shines spotlight on death in Chatham County jail during bipartisan investigation

Note: The Chatham County Sheriff's Office reached out to the Savannah Morning News post-publication for a point of clarification about how the office reports in-custody death data.

A 10-month bipartisan investigation by the Homeland Security and Government Affairs Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (“PSI”), chaired by Sen. Jon Ossoff (D-GA), has revealed the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has undercounted the number of deaths in Georgia prisons and jails over the last two years.

In particular, the investigation revealed the DOJ is failing to effectively implement the Death in Custody Reporting Act of 2013 (DCRA). The law, first passed by Congress in 2000, requires states that receive certain federal funds to report in-custody deaths to the DOJ.

“DOJ’s failed implementation of DCRA 2013 undermined the effective, comprehensive, and accurate collection of custodial death data,” the report reads. “…DOJ’s failure to implement this law and to continue to voluntarily publish this information is a missed opportunity to prevent avoidable deaths.”

One of those deaths not reported and discussed during the hearing was that of Matthew Loflin. He died in Chatham County Detention Center in April 2014. Loflin was one of the 22 people who died at the CCDC between 2009 through 2019, according to Reuters — 50% of those, including Loflin, died from illness, according to the same reporting.

“There is the potential that had DCRA been implemented properly, the trend in illness-related deaths could have been identified and corrective measures taken,” the PSI report read.

A death in the Chatham County jail

Testifying at the hearing, Loflin’s mother Belinda Lee Maley said, “Mothers and sons have a special bond, a bond that no one should ever be able to break. Tragically, in my case that bond was broken. It was broken by a for-profit medical provider."

Will Claiborne, an attorney with the Claiborne Law Firm, represented Maley in her 2016 lawsuit against the CCDC and Corizon Correctional Healthcare, the county jail's former medical services provider. before it was dismissed in 2019.

According to the complaint in the lawsuit, Loflin was detained in CCDC for two months. During that time, Loflin repeatedly begged for medical assistance after experiencing chest pains, but he was denied medical care by both CCDC and Corizon staff.

During those two months, five Signal 55's — emergency warnings for an unconscious inmate — were called for Loflin. Each time, nurses failed to provide necessary health care. Once, we was scheduled for a mental health evaluation. Another time he was given a blanket.

Lawyer:: Medical care at Chatham County jail played role in Loflin's death

During two examinations by a nurse, Loflin was diagnosed with congestive heart failure. A chest x-ray also showed him an enlarged heart and pneumonia. He was coughing up blood. His feet were swelling and his heart was palpitating.

Finally, one doctor recommended he be sent to the hospital. But, per Corizon's policy, Corizon’s regional medical director, Scott Kennedy, needed to approve the request. Kennedy denied the request twice. Instead, he required Loflin undergo two ECG's, which confirmed his previous diagnoses.

Maley was allowed to see her son only once. She and her family placed 23 calls to the detention center to move Loflin to the hospital. Then-jail administrator John Wilcher, and now the current Chatham County sheriff, passed the request to then-Sheriff Al St. Lawrence, who never responded.

Wilcher does not recall the exact details of the case, but he said the decision to ask St. Lawrence to help didn't sound out of the ordinary.

"My thing is, if somebody is sick here, I call the [family member], medical and tell 'em, take 'em to sick call, or if they need to go to the hospital, send 'em. I mean, I'm not gonna sit around and wait around for 'em to die," said Wilcher.

Loflin died in late April 2014.

“I never got to hold him, tell him how much I loved him,” said Maley in the hearing. “The next time I saw him, he was suffering from brain damage…After 32 years of life with my only son, our bond was broken.”

After her son died, then-District Attorney Meg Heap issued the jail a personal recognizance bond, meaning Loflin’s death wouldn’t count as an in-custody death.

“There isn’t justice for my son,” said Maley. But, she said, “I would like to be able to know that our justice system is doing the right thing."

Lawsuit: Family of man who died in Chatham County jail sues jail, health care provider and county

Background: Two internal investigations reveal Creely's death in Chatham County jail 'preventable'

Tough Odds: Creely's turbulent childhood shaped by drug addiction

More: Lee Michael Creely's last hours marked by withdrawal, medical indifference in Chatham County jail

Reporting jail deaths

The PSI investigation reveals the lack of communication between federal entities, specifically the DOJ, and private medical healthcare providers in county jails and state prisons.

Wilcher said he has never reported the number of deaths to the DOJ, but if asked, would oblige.

"If I was supposed to report something to the DOJ, I've never known it, but I have no problem with doing it," said Wilcher. "A death's a death. You can't hide it. We don't hide anything."

Wilcher confirmed that he reports the number of deaths in the jail to the Georgia Sheriff's Association, the Medical Association of Georgia, the District Attorney and the County Manager.

"If we have an open records case, or if we get sued," Wilcher said, "we have to keep all our i's crossed and our t's dotted."

No deaths have been reported to the DOJ by the sheriff’s office since 2019 because the guidelines for reporting deaths in custody changed in 2020. The Georgia Criminal Justice Coordinating Counsel receives those numbers from either the Georgia Bureau of Investigation's medical examiner or the Georgia Department of Public Health death certificate data.

Since 2001, when Wilcher believes CCDC first signed a contract with a private healthcare provider, there have been 44 deaths, including two homicides, 31 natural deaths, nine suicides, one injury from a fall, and one undetermined death. Twenty-one of the 44 deaths, Wilcher said, occurred in a hospital.

The findings about the DOJ’s missing DCRA data worries jail advocacy groups, such as the Vera Institute of Justice, a nonprofit organization working to mitigate mass incarceration.

“The rate at which people were dying in the nation’s thousands of local jails was on the rise prior to the spread of COVID-19, with the smallest jails accounting for the highest mortality rates — but no more recent data is available for what were likely the deadliest years on record,” a Vera Institute of Justice statement read. “Being jailed in the United States should not mean being condemned to die in the shadows of the criminal legal system.”

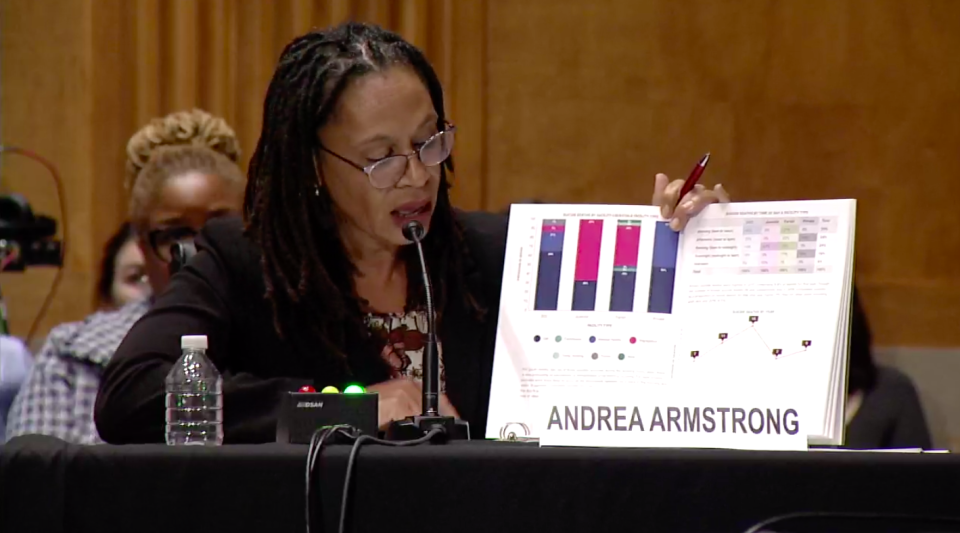

Law professor Andrea Armstrong, of the Loyola University New Orleans College of Law and a national expert on prison and jail conditions, testified in the hearing that without the DOJ reporting DCRA data, it becomes “impossible to fix what is invisible.”

“Increasing public transparency on deaths in custody is a critical step towards ultimately reducing deaths in custody,” said Armstrong.

Maley's attorney Claiborne, who is also representing the family of Lee Michael Creely in another wrongful death lawsuit against the CCDC and Correct Health, its current for-profit healthcare provider, said that the PSI contacted him before last week's hearing to let him know the committee would be issuing subpoenas to his former clients.

"From my view, the number of people who die in jails and pretrial detention in the United States is a scandal hidden in plain sight," said Claiborne. "And the Department of Justice is not even counting how many people are dying. How can we possibly know why they're dying, where they are dying, and how to stop them?

"When you introduce a profit motive into the correctional setting it inevitably leads to the denial of medical care," said Claiborne. "The only way that company makes money is by denying medical care to those inmates. It is a feature, not a flaw, of that contract that medical care is going to be denied."

Drew Favakeh is the public safety reporter for Savannah Morning News. You can reach him AFavakeh@savannahnow.com.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Ossoff committee investigation targets uncounted deaths in jails, prisons