Senior citizens serve at the Stanley Museum of Art and the Hoover Museum, learning valuable history lessons

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

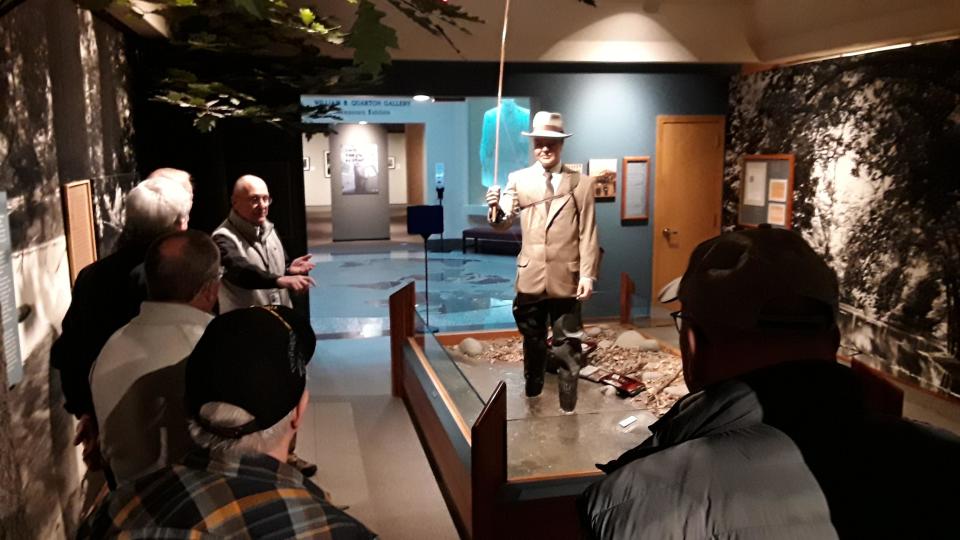

Sign up for a tour of the Hoover Museum in West Branch and your docent might be Frank Buethe of Coralville, an 84-year-old former Marine A4 Skyhawk pilot who served in Vietnam.

Do the same at the new Stanley Museum of Art in Iowa City and your guide could be Sherri Bergstrom, 71, a local Iowa City West High and University of Iowa grad now retired after some four decades of teaching special education.

These two are among a bevy of active area senior citizens who see volunteer museum work as a way to keep sharp, keep learning and keep contributing their talents for something worthwhile.

“In our docent training class of 25 or so at the Stanley, I’m guessing half were retirees,” Bergstrom told me.

Museum officials put that figure even higher, telling me about 80 percent of the 40 volunteers trained at the Stanley during this first year of operation are retirees.

Bergstrom is excited to officially “graduate” from docent training after nearly a year of twice-monthly classes. She has completed “practice tours” with her family and associate curator Josh Siefken, and has the green light to put her docent skills to work later this summer.

Buethe has been guiding tours at the Hoover for about four years. He did the same at the National Museum of Atomic Energy in Albuquerque before resettling in this area five years ago. In New Mexico, he especially enjoyed conducting museum classes for school kids.

“I also really like dealing with kids at the Hoover,” he said. “Most have hardly heard of Hoover, plus it’s fun to get them to think about what life was like without cell phones.”

Bergstrom said when she retired, she vowed “not do anything that I didn’t love.” She had been fascinated for a long time with the extensive African mask collection at the Stanley. That’s because she has made several trips as a volunteer to help establish a school in the Ashante region of Ghana where many of the museum’s masks originated.

“I really didn’t know much about art except that I loved it,” she said.

Now, after months of serious study, she is comfortable speaking about the 600 or so works displayed at the Stanley on any given day.

Both docents told me they were surprised they were not “handed a script” when preparing to lead visitors through these well-respected museums. They have enjoyed the freedom of doing their own research, preparing tours from their own perspective, and spicing their presentations with little-known facts.

An in-depth look behind the scenes

Buethe, for example, likes talking about Hoover’s relief Russian relief program, which suffered through a terrible famine after World War I.

“People don’t realize that the Bolsheviks in Russia had a failing government that was a catastrophe,” he said. “Twenty-three million families were starving and in some cases were reduced to cannibalism.”

Hoover was a master organizer, he said, who spearheaded a successful three-year relief program as Secretary of Commerce that shipped food to the Russian people, plus seeds to restore their crop programs – even earning him a rare letter of appreciation from Lenin.

Buethe also enjoys telling his tour participants about Hoover’s wife, Lou, who attended Stanford University as the nation’s first female geology major. She was also proficient in five languages, headed the National Girl Scouts at one point and was an early advocate for women’s rights.

“She was amazing,” said Buethe. “She translated this complex metallurgy textbook written in 1556 from Latin to English – something nobody could do for 350 years. She was also an excellent amateur photographer. The museum has reels and reels of her home movies in the archives, some of the first filming ever done in technicolor.”

Bergstrom also delights in the many exhibits at the Stanley which have an Iowa connection and interesting hidden stories.

For example, Grant Wood’s very popular “Plaid Sweater” painting, donated by the Mel Blumberg family of Clinton, depicts a pensive seven-year-old Mel in the vintage football apparel of the 1930s.

“Mel loved that sweater so much he cut the sleeves off it so he could wear it in summer,” Bergstrom said. “The sweater was gifted with the painting and is still in the University archives.”

“Corn Country” by Lee Allen is another of her favorite paintings. It displays the influence of Wood, who was Allen’s mentor at the Stone City art colony when Wood lived in Iowa City and taught at the University.

“Allen later became a medical illustrator for surgeries at University Hospitals for many years,” she said. “He also painted prosthetic eyes. A coincidence was that one of my docent classmates said her little brother received one of his eyes.”

The inner-workings of a curator

Bergstrom pointed out that one of the main points in docent training was learning how to properly examine a work of art.

“We were advised to look at pieces very, very slowly,” she said, “and examine things like the color and mood, and to realize there were more things to consider than just the facts of the artist and what their life was about.”

Buethe echoed a similar thought.

“For me, it’s important to try to give people an idea of what Hoover’s personality was,” he told me. “I’m trying to point out things you wouldn’t get just by reading the facts on the wall.”

It goes without saying museum officials are pleased with their senior volunteers.

“It’s not easy being a docent. It’s a lot to ask,” said Siefken. “You wear a lot of hats – guide, entertainer, information specialist, community ambassador.”

The volunteer job is a logical fit for retirees, he said, because most tours take place during what would be working hours for other people.

At the Hoover, Director Tom Schwartz said the museum’s docent program suffered a setback when the museum was closed for two years during Covid, but a new educational director has plans to recruit more volunteers. Seniors also assist with the library archives, he pointed out.

Just so you know, the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum opened on Hoover’s 88th birthday in August of 1962. Besides several permanent galleries detailing his 50 years of public service, there is a temporary gallery for changing exhibits and a 180-seat auditorium.

The Stanley Museum of Art opened in its state-of-the-art, three-story, $50 million building on Burlington Street in August of last year. It rotates exhibits from a collection of nearly 17,000 pieces, one of the most famous being “Mural” by Jackson Pollock, donated to the University by Peggy Guggenheim in 1959.

Classes for docent volunteers are expected to be offered again this fall.

Richard Hakes is a regular columnist and contributor to the Iowa City Press-Citizen.

This article originally appeared on Iowa City Press-Citizen: Local seniors thrive in museums as volunteer docents