From school houses to Charlie’s Place, they fight to preserve Myrtle Beach’s Black history

It’s been 68 years since Patricia Burgess sat in a classroom at the only school for Black children in Myrtle Beach, but she still remembers the dirt road she walked on to get there every winter morning.

“It was important to me because I wanted to learn,” said Burgess, 77. “But it was hard when we were coming up, the dirt was even hard then.”

The Myrtle Beach Colored School was the only place for Black children in Myrtle Beach to get an education from the early 1930s to 1953. A group of former students, including Burgess, spent decades trying to preserve the school after it was no longer in use.

The Myrtle Beach Colored School, a wood-frame building, once sat in the heart of the predominantly Black neighborhood known as The Hill, now called Booker T. Washington. The six-room building was where Black children were educated due to Jim Crow laws that separated Black and white people throughout the Deep South. The laws forced Black children to attend school in one part of town, while white students went elsewhere for school.

“It’s important that kids that go to school today can remember where we came from,” Burgess said. She remembers walking to school with her sister through the forest and trying to learn in small classrooms with hundreds of children. Burgess said she chopped wood for their pot-belly stove to help keep the family’s only source of heat fueled throughout the winter.

Those sacrifices, she said, pushed her to fight for the school’s preservation.

“Just like I tell my grandkids, there is no such thing as ‘you cant,’” Burgess said.

The project to save the Colored School was spearheaded by Mary Canty, who also attended the school. The community leader and former educator was honored by the city in 2013 when they named Feb. 22 “Mary Canty” Day. A community center is also named in her honor. Canty died in 2018.

In 2006, the school was converted to a museum and education center as a part of an ongoing effort to preserve Myrtle Beach’s often overlooked Black history.

“When they came, and we formed the committee, we didn’t have two pennies to rub together,” said April Johnson, a city employee who worked with Canty for almost two decades. “But little did we know. All you had to have was faith believing women and doors began to open.”

The fight to save the school

The Myrtle Beach Colored School opened in 1932. Before the school, Black students were educated in local churches, since they could not attend the white schools. Members of the Black community donated money to get the school built, making up for the lack of county and state support.

The first class of 113 students were taught by three teachers and ranged from first to seventh grade. The school year lasted from October to February, leaving summer months open for students to work hospitality jobs. As the student population increased, the school year got longer. By 1953, 241 Black children attended the school for eight months out of the year.

Leroy Brunson, now 79, remembers being bussed from school to go caddy for white golfers in Myrtle Beach.

“That’s why a lot of the kids didn’t finish school, because they took them out of school,” he said during a television interview. ”A bus would come and they would go pick out whichever caddy they wanted and take him.”

Some students later attended Whittemore School in Conway, the only place for Black teenagers to get their high-school diploma after graduating from the Colored School. Others went out into the workforce to help their families make ends meet.

Burgess remembers having to get out and push the bus when it would break down on its way to the high school. She dropped out of Whittemore to start a family, but got her GED through an adult education program run by Horry County when she was 50 years old.

The Myrtle Beach Colored School was replaced with the Carver Training School in 1953. No longer in use, the once-bustling schoolhouse served as a warehouse for a while, but eventually sat abandoned in the heart of the neighborhood it once served.

In 1978, a group of former students, led by Canty, tried to save the building and failed due to lack of funding from the city. The building sat at the mercy of time and weather for over 20 years.

“We wanted something that was us, that represented us,” Canty told The Sun News in 2013. “We wanted something, too, for our children – for everybody – to know, to see that they were treated justly.”

In 2001, a road widening project threatened the old school building. The City of Myrtle Beach stepped in and appointed former students and community members to a committee tasked with saving the school. Council also provided $10,000 in seed money to help the committee with fundraising.

To raise money, former students compiled family recipes into a cookbook which they sold thousands of copies of to help buy supplies for the museum. Recipes date back to the time of chattel slavery when Black people were fed the undesired parts of animals like pigs feet and intestines or chitlins. They turned them into delicacies.

When the old school building was surveyed, time and weather had taken their toll, and the wooden structure had deteriorated beyond salvage.

With the site of the old school about to be halved by the new road, Burroughs & Chapin donated a site less than two blocks away, where a new “old” school could be rebuilt.

The land was worth almost $100,000 and the city pledged another $350,000 for construction. Cemtex and Horry County Schools also pitched in hundreds of thousands of dollars to get the new structure built.

Canty believed the school should retain its original name. To her, it had always been the Myrtle Beach Colored School, and the former students were unconcerned with whether that name might be uncomfortable or politically incorrect

Segregation was wrong, but it happened, and changing the name now was an unthinkable act of revisionist history, the group told critics at the time..

The Historic Myrtle Beach Colored School and Education Center opened on June 24, 2006. The city organized a limo ride from city hall to the building for the former students who each wore a cap and gown.

Cookie Goings, Canty’s daughter, is carrying on her mother’s work as head of Myrtle Beach’s Neighborhood Services Department. The group gives tours and holds events at the school and has renovated another piece of Black history in the city, Charlie’s Place.

“It wasn’t in the textbooks, there wasn’t any documentation of their story,” Goings said reflecting on her mother’s passion for preserving the school. “They wanted their stories told.”

‘The best damn music in the world’

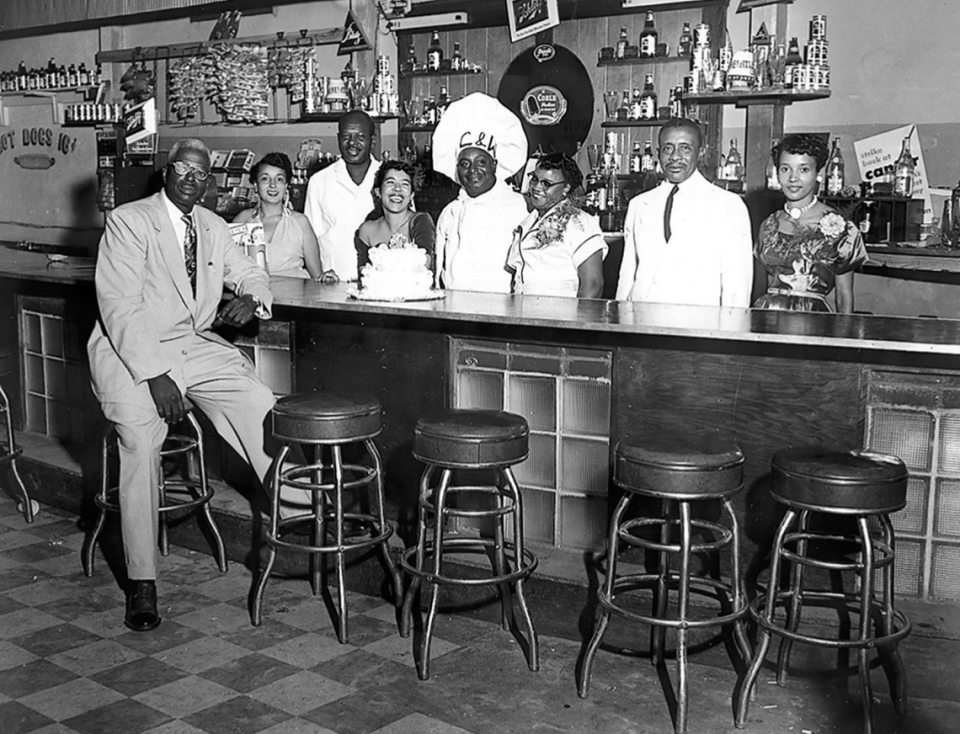

Charlie’s Place was one of the only spots in Myrtle Beach where people from all races got together in the same building. The club would attract the best dancers and was also where many musicians spent the night while touring.

Black artists like Billie Holiday, Little Richard and Otis Redding could perform at the whites-only clubs and hotels on Ocean Boulevard but couldn’t stay at them. They found refuge in the motel rooms that sat on either side of Charlie Fitzgerald’s home on Carver Street. Fitzgerald owned and operated the club from 1937 until 1955.

The club was recognized as a safe place for Blacks in the south in the Green Book, a guidebook for Black travelers. It was also part of the Chitlin’ Circuit, a list of performance venues where Black entertainers could perform. It is recognized as the birthplace of shag, the South Carolina state dance, named after Cynthia Harrol, a Black dancer at the club.

“Charlie was a magnet,” said Roddy Brown, who grew up next to the club. He remembers the posters Fitzgerald would post all over town to announce a big-name artist coming to play. “When those music groups came in, people would flock to Myrtle Beach by the thousands.”

But in the summer of 1950 the Ku Klux Klan attacked the club, beating many and kidnapping Fitzgerald while firing more than 500 rounds into the building after word got around that Blacks and whites were partying, dancing and socializing together.

Dino Thompson said it was the only time anyone raised trouble about Blacks and whites dancing together. Thompson, who is white, would go to Charlie’s to hear “the best damn music in the world,” and pick up new dance moves.

He remembers seeing his first concert at Charlie’s Place when he was 10 years old. The Black chefs at his father’s restaurant walked the young white kid down the road to the club where Little Richard was performing.

After the attack, things at the club went on as normal. Blacks and whites still mixed on the dancefloor and famous artists still played and stayed at the club. Fitzgerald died in 1955 of cancer and his wife Sarah took over the club until 1965.

The buildings sat empty until a few years ago.

‘I never learned about this when I was in school’

The Myrtle Beach Colored School and Education Center will celebrate its 15th anniversary in June, part of a larger Juneteenth celebration. Usually a Black History Month celebration would fill the space with guests but the pandemic squashed those plans.

The coronavirus has also halted most of the after-school programs that the museum offers.

The educational component of the “new” Colored School was something the former students pushed for. They didn’t want the space used for weddings or family gatherings, they wanted it to be a space for people to come and learn, Johnson said.

In normal times, museum volunteers host arts and crafts programs for neighborhood children and provide tours of the museum. The staff are still hosting tours, but in small groups and by appointment only to ensure the safety of visitors during the COVID-19 pandemic

Still, they get people from across the country who stop in to step back in time.

The museum recreates a classroom in one room, complete with desks and books from the segregation era. In another room, visitors walk through a Black history tour of the Grand Strand. Black inventors, politicians and others who have ties to Horry County are honored.

“We get people in here all the time that walk through the museum and tell us ‘I never learned about this when I was in school,’” Johnson said.

‘This is the history of Myrtle Beach and you can’t erase that’

The push to preserve the former nightclub came years after it sat empty and boarded up on the edge of Carver Street. When the city planned to demolish the rundown buildings a group called the Carver Street Economic Renaissance Corporation, led by Herbert Riley, stepped in.

“You can’t find what we got. And when it’s gone, it’s gone,” Riley told The Sun News in 2017 before his death in 2019. “Some of your relatives were in there. That’s your history.”

Riley’s group worked with the city to make sure Charlie’s Place wasn’t forgotten. Eventually the city started restoring the left wing of motel rooms and Fitzgerald’s house. The club and other motel rooms had been demolished after it was discovered they were beyond repair.

Now, the Neighborhood Services department is bringing in local businesses to set up offices in motel rooms and have converted other rooms into a museum. The Fitzgerald house will be used for community meetings and music classes for children. The spot where the club once stood is just a grassy field but transforms to host the Myrtle Beach jazz fest once a year.

Freda Funnye, a native of the Booker T. Washington neighborhood, has been working on the project for almost two years and knows how much the project means to the community.

“It’s a sense of pride that this is in our neighborhood, but it’s also in our city. A lot of South Carolinians and people from Myrtle Beach are proud of this project,” she said.

Funnye is also trying to get the location on the list of historic places from the African American Civil Rights Network, run by the National Parks Service.

Brown, who grew up next to the club, helped the restoration group remember what life was like during segregation. His father owned a business nearby and he saw the white and Black dancers at Charlie’s even after the Klan attack.

Brown said preserving the buildings is important for everyone in the city, not just Black people.

“This is the history of Myrtle Beach and you can’t erase that,” Brown said. “We don’t want to forget that.”