Sentinel ICBM "Struggling," Keeping On Track Will Come At A Cost

Secretary of the U.S. Air Force Frank Kendall says that the development of the future LGM-35A Sentinel nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missile, or ICBM, is "struggling" and that additional costs are emerging. Kendall also said that he viewed the Sentinel program, which is set to include massive infrastructure improvements and other work beyond the LGM-35As themselves, as one of the biggest and most complex efforts his service has ever undertaken and one where failure is not an option.

Kendall made his remarks about the LGM-35A program during a public event that the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) think tank in Washington, D.C. hosted yesterday. The stated plan to date has been for Sentinels to start replacing the Air Force's existing LGM-30G Minuteman III ICBMs, 400 of which are currently deployed in silos spread across five states, in the 2030s.

As of December 2022, the Pentagon estimated the total cost to acquire the full planned complement of LGM-35A missiles and do the other associated infrastructure work to be around $100 billion, according to an official Selected Acquisition Report released earlier this year. In the past, the projected cost to operate and maintain the Sentinels through to the end of the system's expected lifecycle in the 2070s has also been pegged at $264 billion.

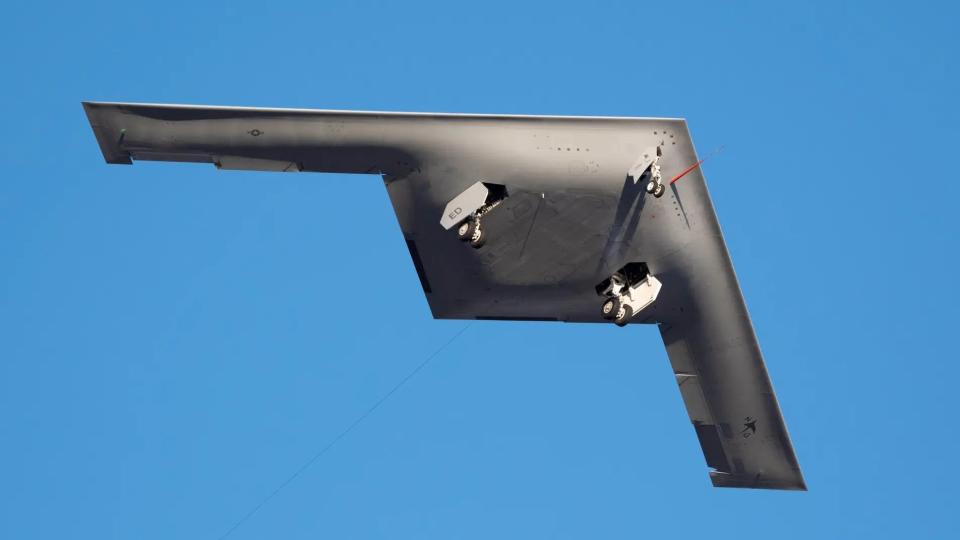

The Air Force's top civilian official also said yesterday he was "cautiously optimistic" about the B-21 Raider stealth bomber program staying on schedule and meeting current cost targets. The initial pre-production Raider just took to the sky for the first time last week and is now set to start developmental flight testing, as you can read more about here.

"My advice to political appointees I've worked with for decades has been: never say something positive about a program that's in development. They all have risk," Kendall said. "There is a good chance that whatever program it is, no matter how well it's done to date, it's gonna get in trouble in the future."

"I'm fairly optimistic comparatively about the B-21," he continued. "Sentinel, I think is quite honestly struggling a little bit."

Kendall is an Air Force veteran and career U.S. government bureaucrat, but has also spent time working in the private sector. This includes consulting for Northrop Grumman, which is the prime contractor for both the B-21 and the LGM-35A. As a result, he has recused himself from decisions regarding either program to help avoid any accusations of impropriety. This also limits what he can say about them, though he was able to elaborate to a degree on the issues facing Sentinel.

"There are unknown unknowns that are surfacing that are affecting the [Sentinel] program," the Air Force Secretary said. "It's been a very long time since we did an ICBM."

The first of the Air Force's existing LGM-30Gs entered service in 1970, but were still based on the core Minuteman design that was developed in the 1950s. The Air Force had developed and fielded a new ICBM, the LGM-118A Peacekeeper, in the 1970s and 1980s. However, those missiles were removed from service in 2005 as a result of arms control agreements between the United States and Russia.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RHlYc_MzvLk

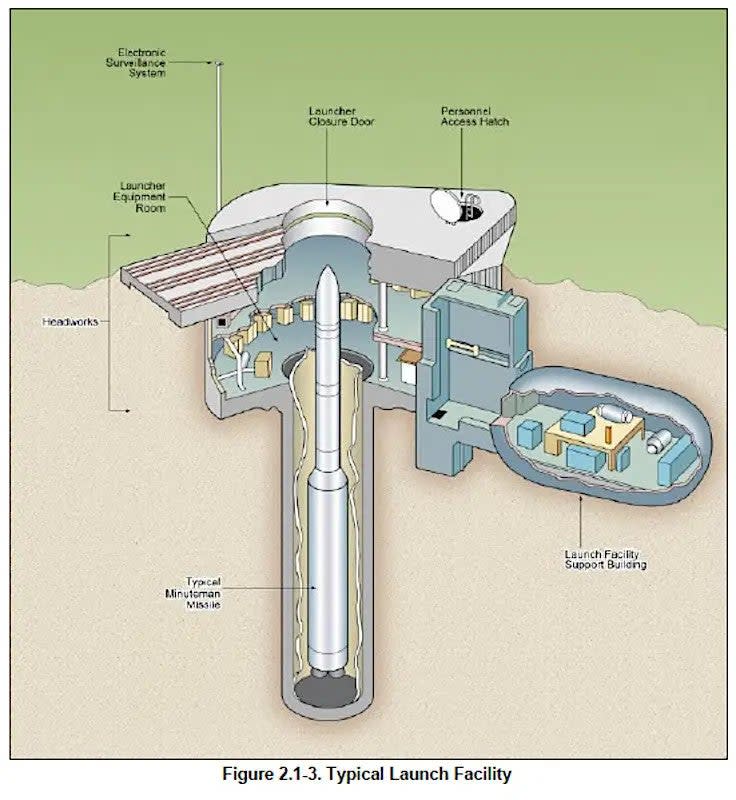

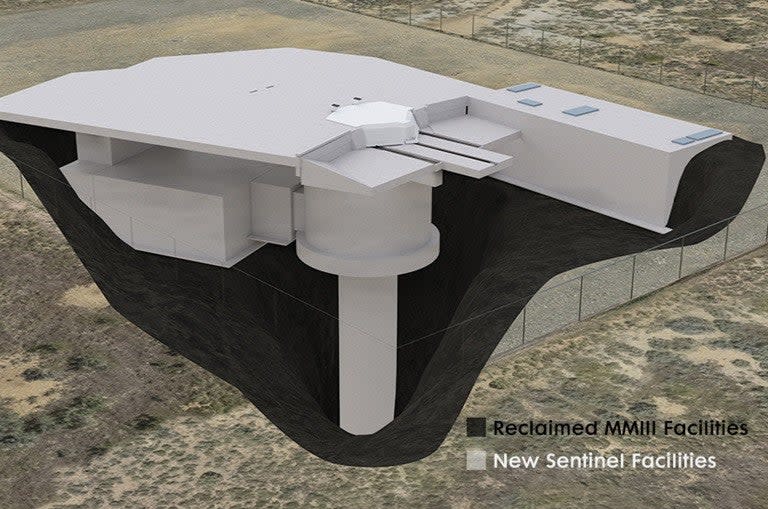

"Sentinel is one of the most large [sic], complex programs I've ever seen," Kendall added. "It's probably the biggest thing, in some ways, that the Air Force has ever taken on because it's a vast real estate development/civil engineering program, [and] a fairly vast communications, command and control Program, as well as of course the missile itself."

The Sentinel program also has to "go into all those complex real estate/deployment [questions] ... the missile fields, plus the launch control complexes, etc, all the command and control infrastructure," he explained. "We had to go assess all that to see what might need to be replaced and how hard that job was going to be."

"So, as we get more into the program, as we understand more deeply what we are actually going to have to do we're finding some things that are going to cost money," he continued. "There's no question about that."

Kendall declined to provide more explicit details due to his recusal. However, the unclassified version of the Fiscal Year 2022 Selected Acquisition Report for Sentinel says there were no major technical risks to the program, at least officially, as of the end of last year. Instead, concerns about schedule delays, and by extension cost increases, were linked to economic and other factors.

"Sentinel is experiencing schedule pressures due to macroeconomic factors affecting the industrial base because of [the] COVID-19 [pandemic]. Volatility in the supply chain is causing increasing lead times for parts and components that are extending to commodities," according to the report. "These pressures eliminated margin or pushed forecasted major program events dates past their baseline."

The report also cited recruiting challenges and efforts to expand the available "talent pool," issues that speak to Kendall's comments about the complexities that just come from the United States not having designed or built a new ICBM in decades.

As a result, "Sentinel is actively engaged with resolving identified risks and is conducting a schedule assessment," the Selected Acquisition Report says.

It is worth noting here that the Air Force considered, but ultimately rejected the possibility of acquiring one of a number of potentially lower-cost alternatives to the LGM-35A. These options included a siloed version of the U.S. Navy's proven Trident II submarine-launched ballistic missile, as well as a new smaller missile with intercontinental range or a design based at least in part on an existing commercial space launch rocket. The service also explored launchers positioned at the bottom of lakes or in tunnels as alternatives to loading Sentinels into existing silos, and therefore obviating the need to upgrade them, but decided against those basing concepts. You can read more about all of this, and the Air Force's justifications as they are known, here.

There are no indications currently that the U.S. government might be inclined to cancel Sentinel due to potential schedule delays or cost growth, or any other reasons. America's main potential nuclear opponents, China and Russia, are pushing ahead with their own new IBCM programs, as well as other nuclear modernization efforts.

The Pentagon currently estimates that the Chinese have around 350 ICBMs of various types, in total. Some of these are now believed to be loaded into new sprawling silo fields in various parts of the country, which are also viewed as indicative of China moving to a so-called launch on warning deterrence posture. This refers to a preparedness to launch a nuclear retaliatory strike in response to an enemy nuclear strike, but before any of those incoming warheads detonate.

The Chinese military may even be considering acquiring a new conventionally-armed IBCM capability, which presents its own unique concerns for the United States. In addition, the U.S. military assesses that China's overall nuclear stockpile has significantly grown and is continuing to do so, with more than 500 warheads now and as many as 1,000 by 2030.

"We have to do them," Kendall said yesterday about Sentinel and B-21. "Somebody asked me about being willing to fail on programs. I said, well, there are some programs you cannot fail on. ... Both of these [are] part of the triad of programs we must succeed in getting through."

How much more it will ultimately cost and how much extra time it might take to keep Sentinel on track in the face of the emerging "unknown unknowns" remains to be seen.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com