Sergei Khrushchev, son of Soviet leader Nikita who ended up swearing allegiance to America – obituary

Sergei Khrushchev, who has died aged 84, was the son, confidant and champion of the former Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev; yet in later life, he became an American citizen and a professor of international relations at Brown University in Rhode Island.

During his father’s years in power, the younger Khrushchev, who bore a striking physical resemblance to his father, participated in the Soviet missile and space programme, working on cruise missiles for submarines, military and research spacecraft, moon vehicles and the “Proton,” the world’s largest space booster. He was the author of many books and articles on engineering and computer science and won the Lenin Prize for his work.

After his father’s fall from grace, his scientific career stalled and in the 1970s he began a new career as a writer and lecturer. As the Cold War neared its end, he wrote Khrushchev on Khrushchev, winning an invitation in 1990 to lecture at Harvard, followed by a visiting professorship at the Watson Institute for International Relations at Brown University.

During the 1990s he wrote extensively about the history of the Cold War and the turning points in the relationship between the West and the Soviet Union during the Khrushchev, Eisenhower and Kennedy periods. He edited his father’s memoirs and also wrote Nikita Khrushchev: Crisis and Missiles; The Political Economy of Russian Fragmentation, Three Circles of Russian Market Reforms and Nikita Khrushchev and the Creation of a Superpower.

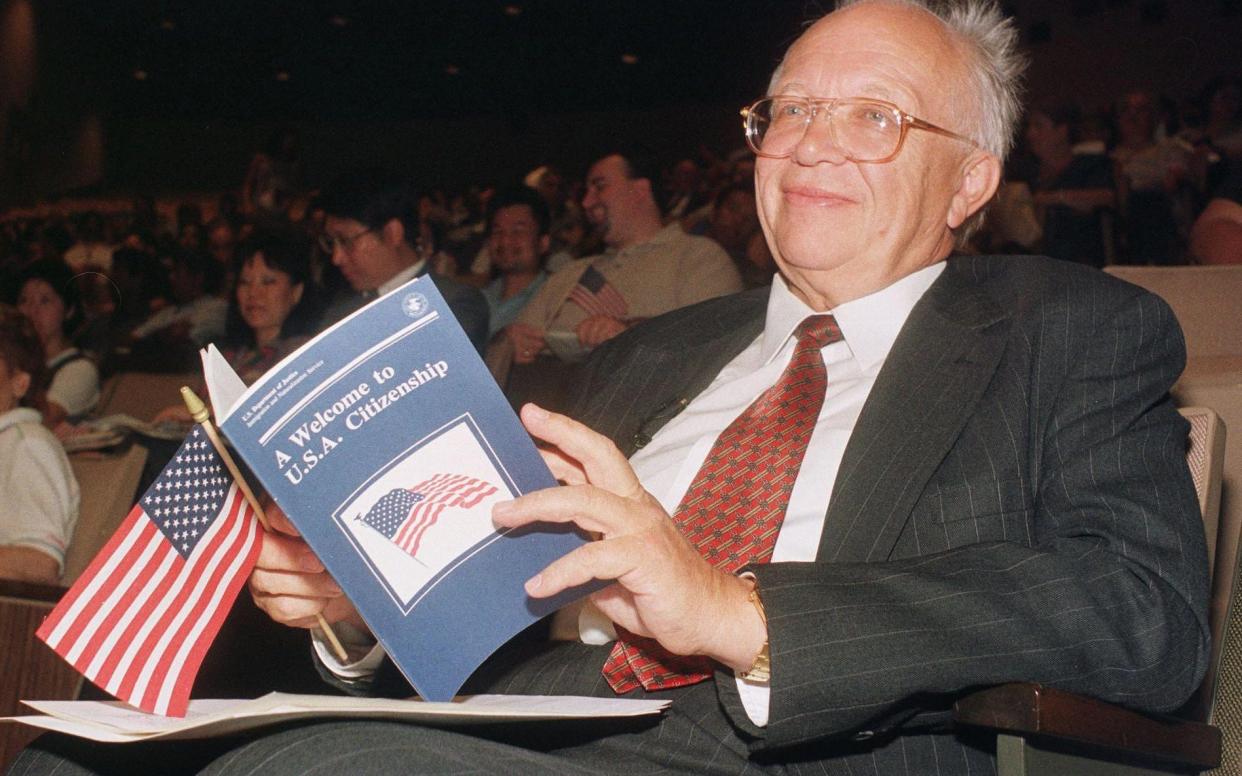

The sight, in 1999, of Sergei Khrushchev raising his right hand to swear allegiance to the old enemy was one of the more delicious ironies of the post-Cold War era. But Khrushchev insisted that his father would have understood. “He was in the Communist Party because he believed it would be best for all of us. If, like me, he had seen that capitalism ended up working better, maybe he would have come to America, too.” His decision to take American citizenship, he felt, was a sign that the Cold War was truly over. “Stalin’s daughter defected to America. She fled amid great secrecy. Me? I just bought a ticket.”

One of five children and a second son, Sergei Nikitich Khrushchev was born on July 2 1935. By his account his father, the man who dispatched nuclear missiles to Cuba and threatened to “bury” the West, was an old softie at heart. His mother, Nina, was the disciplinarian, insisting that her son got no preferential treatment at school and lecturing him on his duties to the Revolution.

Against the backdrop of hardship in Russia, theirs was a life of privilege. At their homes Kiev and in a dacha outside Moscow, there was always freshly baked bread on the table and wine to drink. The family sang songs or told stories by the fire and Sergei grew up surrounded by a menagerie of animals- rabbits, ducks, geese, guinea fowl, as well as random animals brought in from the woods.

Sergei’s only brother, Leonid, was killed when his fighter went missing in the Second World War. Sergei then became his father’s main confidant, accompanying him on the vigorous walks the elder Khrushchev enjoyed after a hard day at the office. During the worst years of Stalin’s tyranny, his father was always expecting the midnight “knock on the door”. Sergei acknowledged that if Stalin had lived another five years, none of them would probably have survived. “You could not just be fired from the job. You would be eliminated. And so would your family.”

Sergei Khrushchev graduated in engineering from Moscow University in 1958, a year after Sputnik, and rose to be a deputy department chief in the Soviet space programme. He remained proud of his scientific work, though it remains unclear how much his status as a scientist owed to his privileged access to the Kremlin.

In 1956 he travelled to London with his father as part of his official entourage, encouraged to gather any data on Western technology that he could. He recalled being astonished to see how full the shops were, and how the people on the streets had food, and had to use considerable guile to persuade his father to part with some precious foreign currency as spending money. When Sergei announced, with some delight, that he had been given an invitation to visit Oxford, his father refused him permission to go, on the grounds that it was probably a kidnap plot. Returning to Moscow, father and son concluded that the British probably did not want war. “They were content, and seemed satisfied to be getting rich.”

He was at his father’s side, too, during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, which he regarded as an American “psychological crisis,” brought on by the realisation of their vulnerability to nuclear attack. In fact, he insisted, the Americans were under greater threat from missiles based on Russian soil than from anything stationed in Cuba. By his account, it was after Khrushchev learnt that Cuban president Fidel Castro was making a case for a first strike that he ordered the missiles to be pulled back, deciding that the best way to get the message to President Kennedy was via an open broadcast on Radio Moscow.

Years later Sergei Khrushchev revealed how the message nearly failed to get through. On the way from the Kremlin to the radio station, the driver carrying the message got lost in the city and arrived late. Then the messenger jumped into a cage lift which broke down between floors. In the end the messenger had to rip open the envelope and pass out the pages through the bars one by one. Finally, the Radio Moscow announcer was able to read the message that defused the crisis.

It was Sergei who first got wind of his father’s impending political deposition – through a telephone call from a friend in the Kremlin – in 1964. Nikita Khrushchev dismissed the rumours as tittle tattle, but two days later he “retired.” Subsequently Sergei was moved from rocket design to computers. “My department grew from five to 500 people, but there was no promotion.” In retirement Nikita Khrushchev worked on his memoirs, which his son edited after his death in 1971 in the face of official disapproval.

It was not until the end of the Cold War that Sergei Khrushchev was able to begin a new career – in America – and it did not take him long to decide that he liked the country: “Americans are very friendly. If you ask for directions in the street, they do not turn and hurry away, as if afraid, but show you right to where you want to go. And in Russia, all the computers are falling apart. Here, they work.”

After eight years, he and his wife Valentina Golenko decided to apply for American citizenship. He fluffed only one question in the written tests. When asked “What kind of government does the USA have?”, he answered “executive”, rather than “democratic”. “Language problems,” explained Khrushchev, tactfully. Notwithstanding his new national allegiance, he regarded America as the more ideological of the two countries.

Sergei Khrushchev had three sons, all three of whom continued to live and work in Moscow even as their father forged a new life in surburban Rhode Island. One, Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (from an earlier marriage), died of a stroke in 2007.

Valentina survives him.

Sergei Khrushchev, born July 2 1935, died June 18 2020