As a serial killer moved like a shadow across Charlotte, one woman made a promise

My last phone call with Barbara Rippy took us to a familiar place: her decades-old anger over the plight of the seven children left motherless by Charlotte mass murderer Henry Louis Wallace.

“Write something for the kids,” she urged me in September, on the eve of her 83rd birthday. “Nobody in that state has ever done a damn thing to help them.”

We’d been talking on the phone regularly since 2018, when I met her while reporting a story on how one of those motherless children — with Rippy’s lifelong devotion — had overcome the trauma of her early life to graduate from college.

That story never appeared in time for Rippy to read it. She died of leukemia on Dec. 1, 2022. During our conversation in the fall, she talked about her plans to move back to Charlotte. She never told me she was sick.

Yet, something about her final plea — “Write something for the kids” — still resonates.

Thirty years ago in the midst of Wallace’s murder spree, Rippy made a promise that changed the course of her life and that of a baby girl named Natalia.

In our final conversation, I told Rippy I would do what I could to publish the story she and the other survivors of Wallace’s 22 months of terror deserved — a story of violence and loss and how families born from tragedy struggled to build new lives.

Rippy kept her promise. Now, I’m keeping mine.

Barbara Rippy knew something was wrong the instant she spotted the open door.

Vanessa Mack’s apartment off Wilkinson Boulevard was always locked tight. Each time Rippy visited, she’d knock, then wait. Invariably, Mack would come to her kitchen window first, checking once, twice, even three times before she’d let Rippy in.

A Killer's Long Shadow

30 years ago, Henry Louis Wallace cast a murderous shadow across Charlotte, raping and strangling 10 women before his arrest. Wallace's killings broke up families, stole daughters and sisters from their loved ones and left seven children without their mothers.

As a serial killer moved like a shadow across Charlotte, one woman made a promise

In 1994, Charlotte police searched for a murderer. They caught a serial killer instead

11 victims in two states: A timeline of Henry Wallace’s killings in Charlotte and SC

In February 1994, Mack had reason for caution. At 25, she was a single mother struggling to raise two young daughters in a city that no longer felt safe.

For the better part of a decade, crack cocaine had been streaming into Charlotte’s neighborhoods. Killings were occurring in record numbers — 132 in 1993 compared with 48 five years earlier.

Rippy also knew that Mack feared something else.

For weeks the younger woman had been tormented by the same nightmare — a desperate, night-long race to escape the devil. When she’d awaken, Mack would find herself gasping for air, as if the chase had crossed over into waking life, and something or someone was closing in.

“If anything happens to me,” Mack had asked Rippy three days earlier, “will you take care of my girls?”

Rippy, then 54, had raised six children of her own. But she had ties to Mack’s two girls.

Natara, 7, whose father was Rippy’s son, often stayed at Rippy’s home in Pineville. Rippy also looked after 4-month-old Natalia when Mack worked as a patient’s aide at Carolinas Medical Center.

That Rippy was so involved in the girls’ care made it easier for her to envision them as her own. Nonetheless, she well understood the significance of what she was being asked to do.

“You make a promise like that to someone,” Rippy told me years later, “you’re really giving them your life.”

Yet, she answered Mack’s request with a question of her own:

“What’s going to happen to you?”

The wail of sirens

A little before 6 a.m. on Feb. 20, 1994 , Rippy stood on Mack’s back stoop. She paused, then pushed through the open door and into the darkened apartment. Mack’s keys, attached to a fob decorated with her daughters’ photographs, dangled from the inside lock.

Rippy called out Mack’s name. No answer.

She found her way across the kitchen, talking louder as she went, and flipped on the overhead light.

“Vanessa, wake your ass up,” Rippy remembered saying in a near shout. “You’re going to be late.”

Still no reply.

Then she saw Natalia. The baby was lying on her stomach. Not in the crib kept in her mother’s bedroom, but on the living room sofa. She had propped herself up with her arms and was smiling. Natara was already at Rippy’s home in Pineville, still asleep.

Confused and more alarmed, Rippy walked toward Mack’s bedroom, reached in and found a light switch. Then she gasped.

Mack’s body was strewn across the foot of her bed. A pillow case was tied around her neck along with another piece of fabric — which was white and had deer on it. Mack had been strangled with her daughter’s baby blanket.

Rippy touched Mack’s left foot and the fingers of her left hand. They were cold.

Trembling, Rippy retraced her steps to the living room. She picked up the baby, dialed 911, then made her way to nearby parking lot as the wail of approaching police sirens continued to build.

She cradled Natalia, the two of them already bound by a promise Rippy never imagined she’d have to keep.

The killer

Autopsy ME-94-1591 found that Vanessa Mack had been raped before she was strangled.

Within days, police told Rippy that the killer tried to use Mack’s bank card at a nearby ATM but failed. Rippy had always told Mack to keep her PIN secret. Mack had listened and given her attacker the wrong number.

At Mack’s apartment, detectives found no fingerprints or signs of a forced entry. At first, police focused their investigation on Mack’s former boyfriend, who failed two lie-detector tests, but he was never charged. Two weeks passed, and the search for Mack’s killer began to go cold.

On March 9 , there was another body, this time in east Charlotte. And then another, and another still. All the victims were Black women, and the manner of some of their murders hearkened back to Mack’s.

On March 13, police found Henry Louis Wallace hiding in a friend’s east Charlotte apartment. In all, he confessed to the killings of 10 women in Charlotte as well as an 11th victim, a teenager, in his hometown of Barnwell, S.C.

Wallace told detectives that he fell in love with Mack the first time he saw her and that he had doted on Natalia. Yet, he went to her apartment in February 1994 to rob, rape and kill her.

When he knocked on her door, Wallace said, he was carrying a pillow case inside his coat. Inside Mack’s apartment, according to court documents, he asked for a drink.

When Mack turned to get him one, Wallace used his pillow case as a garrote to drag Mack into her bedroom. There, he demanded money, her bank card and PIN, as well as sex. Mack was too frightened to resist, he told police.

Later, Mack asked to be allowed to check on Natalia, who was on the sofa. Wallace told police he loosened his grip as if to let Mack get off the bed, then quickly twisted the pillow case even tighter. He wrapped another piece of fabric — Natalia’s baby blanket — around Mack’s neck to maintain the pressure.

Wallace did not leave the home until Natalia fell asleep, he told police. He kept the back door ajar, he said, so Mack’s neighbor could reach the baby if she started crying.

A week later, Mack was buried in a small cemetery near York, S.C., the only plot Barbara Rippy could find on short notice.

At Rippy’s direction, Mack’s casket was closed 10 minutes before the start of the funeral, just as Rippy entered the church with Natalia and Natara, and the three of them made their way to the front row.

Rippy believed until the end of her life that Wallace was sitting among the mourners.

On the witness stand

Some 2 1/2 years later, Rippy testified at his trial.

Sitting at the prosecutor’s table, then Mecklenburg Assistant District Attorney Anne Tompkins was struck by how Rippy commanded the courtroom.

“I do remember her testimony,” Tompkins, later a U.S. Attorney for the Western District of North Carolina, told me a quarter of a century later. “How strong she was. How amazing. How gripping.”

Rippy told me that her composure teetered slightly when she recalled how she was told on the morning of the murder to keep Mack’s daughters until social workers could arrange to pick them up.

“I said, ‘Nobody’s going to take this baby away from me,’” she testified. “Vanessa asked me to raise her children if anything ever happened to her. I made her a promise.”

When Rippy left the witness stand, she was in tears. She said they were tears of anger, and that she would have strangled Wallace in the courtroom if given the chance.

On Jan. 7, 1997, two years and 10 months after his arrest, Wallace was convicted of nine murders. Three weeks later, the same jury sentenced him to death.

The families

As Wallace moved to Central Prison, his victims’ families attempted to stitch together some semblance of a new life but found the trauma hard to escape.

Dee Sumpter, the mother of 20-year-old Shawna Hawk whom Wallace killed in February 1993, helped start a nationally acclaimed organization called “Mothers of Murdered Offspring.” In March, it celebrated its 30th anniversary.

Yet, decades after her daughter was found in the family’s bathtub, Sumpter told me in 2018 that she was “still trying to breathe.”

“Life does go on,” she said. “But what kind of life are we talking about? What are the day-to-day mechanics of this life? Can someone define that for me?”

By the time Wallace’s trial ended in 1997, Rippy had relocated to Florida with her new family. As she promised Mack, Rippy formally adopted Natalia and was raising her and Natara.

Within a year, her husband Julius was dead from complications from diabetes. At 56, Rippy was a single mother.

As a toddler, Natalia loved jewelry and dolls and trips to the beach. There were photographs of Mack throughout the apartment, but the difficult subjects surrounding the mother’s absence did not come up.

“Little girls,” Rippy told me, “don’t ask many questions.”

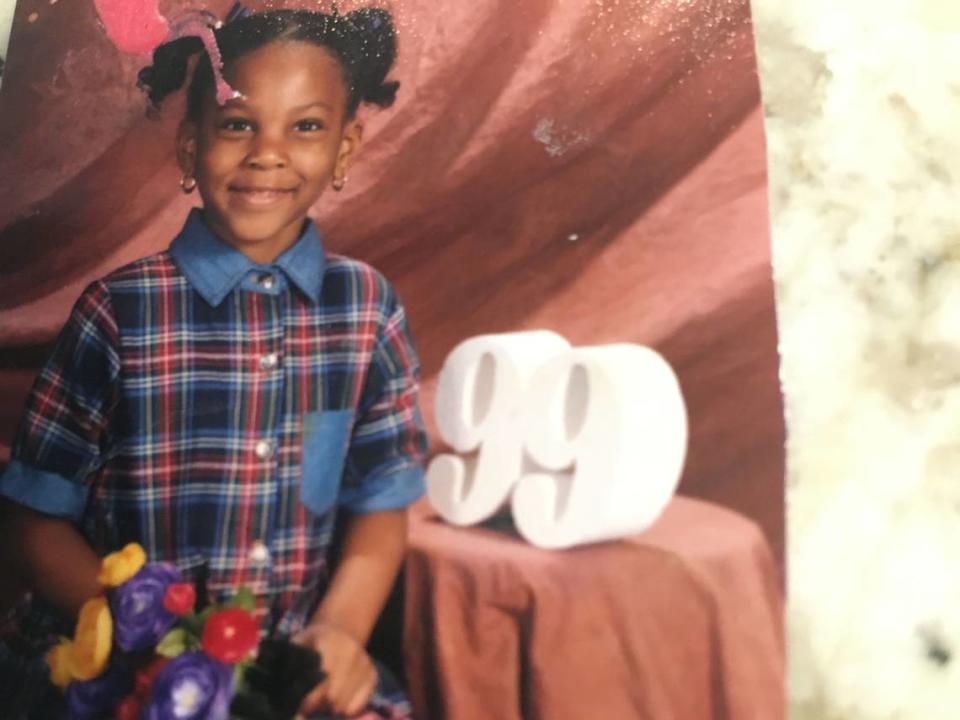

In 2003, when Natalia was in third grade, she drew a portrait of herself for a school assignment on what she wanted to accomplish that year in Mrs. Copeland’s class. She gave herself two ponytails, gold earrings and blue shoes, and she used big, elementary-school letters to spell out her goals.

“I want to get all A’s,” she wrote. “Go to college to be smart. And I want to graduate.”

But it was Natalia with whom Rippy struggled most. It was also Natalia with whom she had the most in common. Both had to deal with loss at an early age. Both were raised in families other than the ones into which they were born.

In 1939, Rippy was delivered in a makeshift Monroe hospital for Black mothers. Three days later, she says, her mother left her. She never knew her father.

Rippy was 8 before she learned from a playground taunt that the only parents she had ever known were actually her birth mother’s cousin and her husband. She barreled ahead, she says, by embracing the family she did have.

“But you always wonder,” she told me. “What did you do for your real parents to run off?’’

Natalia also grappled with ghosts: a father who wasn’t around, a mother who was not allowed to be. Henry Wallace had warped the direction of her life, years before she was able to see it.

“There was a lot of anger and confusion, I guess, feeling like a part of me was missing, not knowing who I exactly was or where I came from,” Natalia told me in 2018.

Relationships to her seemed fractured and brief. She once told Rippy, “I feel like I don’t belong to anybody.”

As she grew older, her battles with her adopted mother became more frequent. Rippy partly blamed herself.

“I was hard. I was hard on everybody,” she said. “Natalia thought I was mean, and she thought I was only being mean to her because she wasn’t my child.”

The relationship ruptured when Natalia was 13. She, Natara and Rippy had returned to North Carolina and were sharing a home in Monroe. One morning before school, Rippy told Natalia to turn off the TV and come to the table for breakfast.

Without warning, Rippy recalled, Natalia slammed a filled plastic water bottle into the left side of her head near her eye. Rippy reeled in shock and pain. Police came to the house. It was not their first visit.

Two days later, with Rippy’s signature, Natalia became a ward of the state.

For the first time since her mother’s death, she and Rippy were no longer together, and Natalia spent most of her high school years shuffling between a group home and foster care.

She said she saw Rippy’s decision to give her up as a betrayal.

“I felt rejected. I felt alone,” Natalia told me during a 2018 phone call. “I think it made me, like, cold. I had problems developing relationships. I didn’t know how to get close to people.”

During the separation, Rippy says she tried to stay in touch. But she said she wondered some nights whether Natalia was gone for good.

Their reunion came begrudgingly. At 18, when Natalia aged out of state care and graduated from high school, she and Rippy remained at an impasse. So, leading up to her high school graduation, Natalia lived for several weeks with a teacher from her school.

Afterward, Rippy paid for Natalia to have her own small apartment in the same Monroe complex where Rippy lived. They saw each other every day. Rippy took her shopping, and drove her back and forth to junior college. Natalia also had her privacy and was slowly learning to live on her own.

In this routine, and with time, they re-established their family ties.

“There is forgiveness,” Natalia told me.

There is resilience, too.

“I went through hell with Natalia,” Rippy told me in 2018. “But I’m still standing here beside her.”

The promise

It was during her college years, first at Johnson C. Smith and finally at East Carolina University, where Natalia says a healthier relationship with Rippy firmly took root. Emotional ties that had endured tragedy and estrangement slowly brought them back together.

Drawing from her own struggles to understand her life and her feelings, Natalia majored in psychology at ECU. She told me in 2018 that she was interested in learning “what makes people what they are.”

Dee Sumpter says the life Rippy and Natalia wrested from the hands of Henry Louis Wallace can be an example for others fighting the undertow of violent loss.

“There are these moments of redemption where the pain almost becomes worth it,” she said. “My lord. All I can say is, my lord. The Rippys of the world ... I am in complete awe.”

In the spring of 2018, as Natalia finished her final college classes, she told Rippy that she did not want to attend her graduation.

“I told her, ‘You owe it to yourself,” Rippy said a few days before the ceremony. “’And the second person you owe it to is me. I want to see that man hand you the piece of paper. Then your momma will know I did my job.’”

In May 2018, Rippy, then 79, caught a plane from Orlando to Charlotte. The next morning, she joined her daughter Quintina and her son-in-law Fred for the four-hour drive to the East Carolina campus in Greenville.

Around noon that day, Natalia Little — she uses Mack’s maiden name — walked across the stage and received her diploma. The return path to her seat brought her within a few feet of her adoptive mother.

“Good job,” Rippy said as Natalia passed by.

A family portrait

The next day, Natalia and Rippy shared a couch in the small house at the back of a Harrisburg cul-de-sac that belonged to Quintina and Fred.

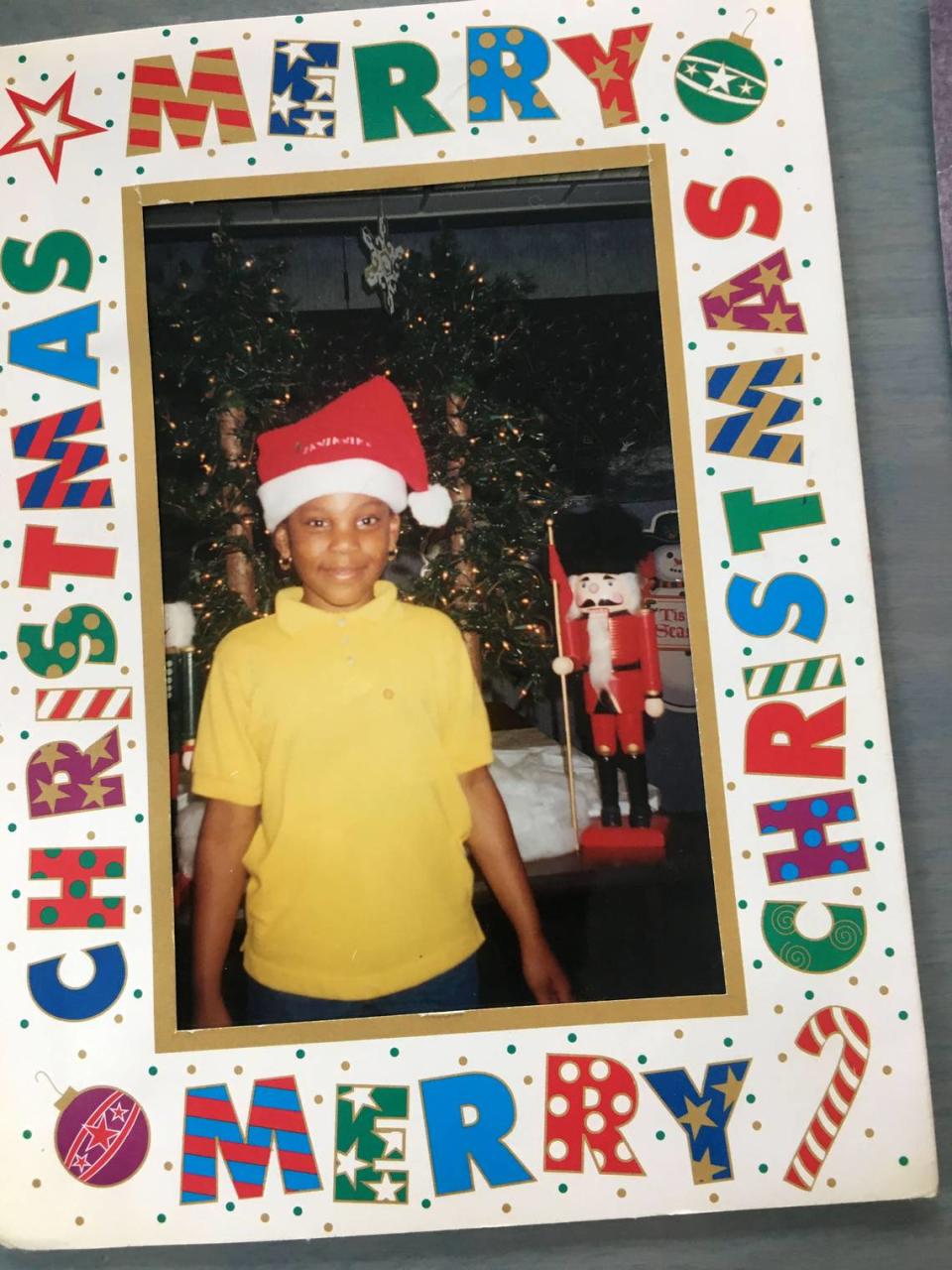

The two women were surrounded by photographs. One dated back to Christmas 1993, when Rippy arranged to have a family portrait done at a Kmart in west Charlotte.

Rippy told me that Vanessa Mack wanted no part of the photo shoot. Rippy insisted and drove the family there herself. She bought Mack a Christmas sweater, along with new outfits for Natara and Natalia. She also paid for the photographs, which Rippy said were the only ones ever taken of Mack with her daughters.

In the portrait, Natara grins cheek-to-cheek. Natalia, then 2 months old, gazes upward with a look that resembles wonder. As she holds her daughters, Mack manages a half smile. She had two months to live.

In October, the baby in the photograph turns 30, five years older than her mother lived to be.

“I think about that often,” Natalia said the day after graduation. “Maybe I’m living and experiencing stuff that she exactly did not get to live through or do. Just like, I’m walking this path, and I’m walking it, and I’m sure I’m making her happy.

”I’m doing the best that I can, that’s all I can say, ” she said. “It feels like I’m doing what I can to make her and my mom here (Rippy) proud.”

A few feet away, Rippy stopped picking through the photographs. Thirty years ago, she found an orphaned baby on a sofa. Now, she seemed to be studying the woman the little girl had become and what the future still might hold for both of them. A tear rolled down her cheek.

Promise kept.

Epilogue

Today, as the 30th anniversary of her mother’s death approaches, Natalia Little lives in Charlotte and is the mother of a young daughter, Amora. Her sister Natara Briggs, 36, still lives in Florida.

After agreeing to multiple interviews in 2018, Little declined to talk to me this spring and summer. She told me in a text message that with Rippy’s death, she and Natara are on their own, and, as with other survivors of Wallace, have never received the help they needed or deserved.

This story includes Observer reporting from 1992-94.