Serial killer strangled his mother. Now, he says, it’s Henry Wallace’s turn to die

Tyrece Woods doesn’t remember his mother. How Brandi Henderson laughed. The way she moved. The warmth of her touch.

Nor does he recall her death.

But he believes that something from that night of horror almost 30 years ago, when Henderson was raped and strangled by her boyfriend’s best friend — Charlotte mass murderer Henry Louis Wallace — seeped into his very bones.

On March 9, 1994, Henderson, 18, was holding her 10-month-old son when Wallace sexually assaulted and garroted her inside her east Charlotte apartment. Wallace later told police that in her last moments, Henderson got on her knees and prayed.

Tyrece, the killer confessed, wouldn’t stop crying. Wallace gave him a bottle and a pacifier. Neither worked. So Wallace tied a pair of shorts around the infant’s neck and choked him until he quieted down.

“I find it ironic that I’m claustrophobic,” the now 30-year-old Woods says over the phone during a March interview with The Charlotte Observer. “Small rooms. People putting their hands near or on my neck. If I feel I can’t breathe. I go crazy. I really freak out.”

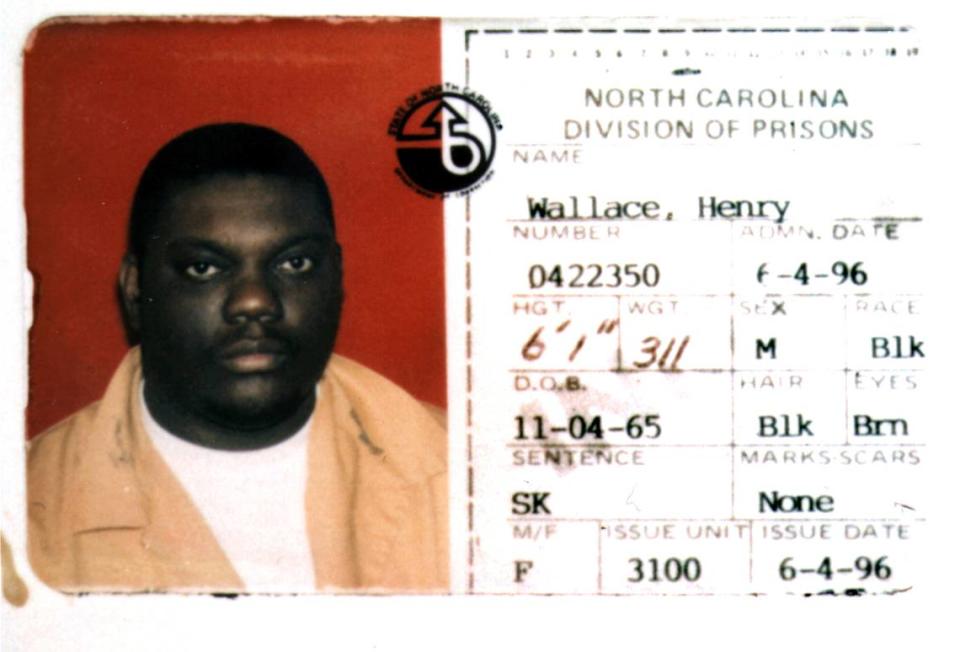

Wallace, who was arrested less than a week after Henderson’s killing, eventually confessed to murdering 10 women in Charlotte over 22 months. In 1990 he also raped and strangled a high school student in his native Barnwell, S.C..

Wallace, now 57, has been on Death Row since 1997.

A Killer's Long Shadow

30 years ago, Henry Louis Wallace cast a murderous shadow across Charlotte, raping and strangling 10 women before his arrest. Wallace's killings broke up families, stole daughters and sisters from their loved ones and left seven children without their mothers.

As a serial killer moved like a shadow across Charlotte, one woman made a promise

In 1994, Charlotte police searched for a murderer. They caught a serial killer instead

Serial killer strangled his mother. Now, he says, it’s Henry Wallace’s turn to die

Henry Wallace killings exposed flaws in CMPD homicide investigations, sparked changes

11 victims in two states: A timeline of Henry Wallace’s killings in Charlotte and SC

“There’s no excuse,” the killer told Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police investigators after his March 1994 arrest. “There’s no way I can say I’m sorry to the children who have to grow up without a mother.”

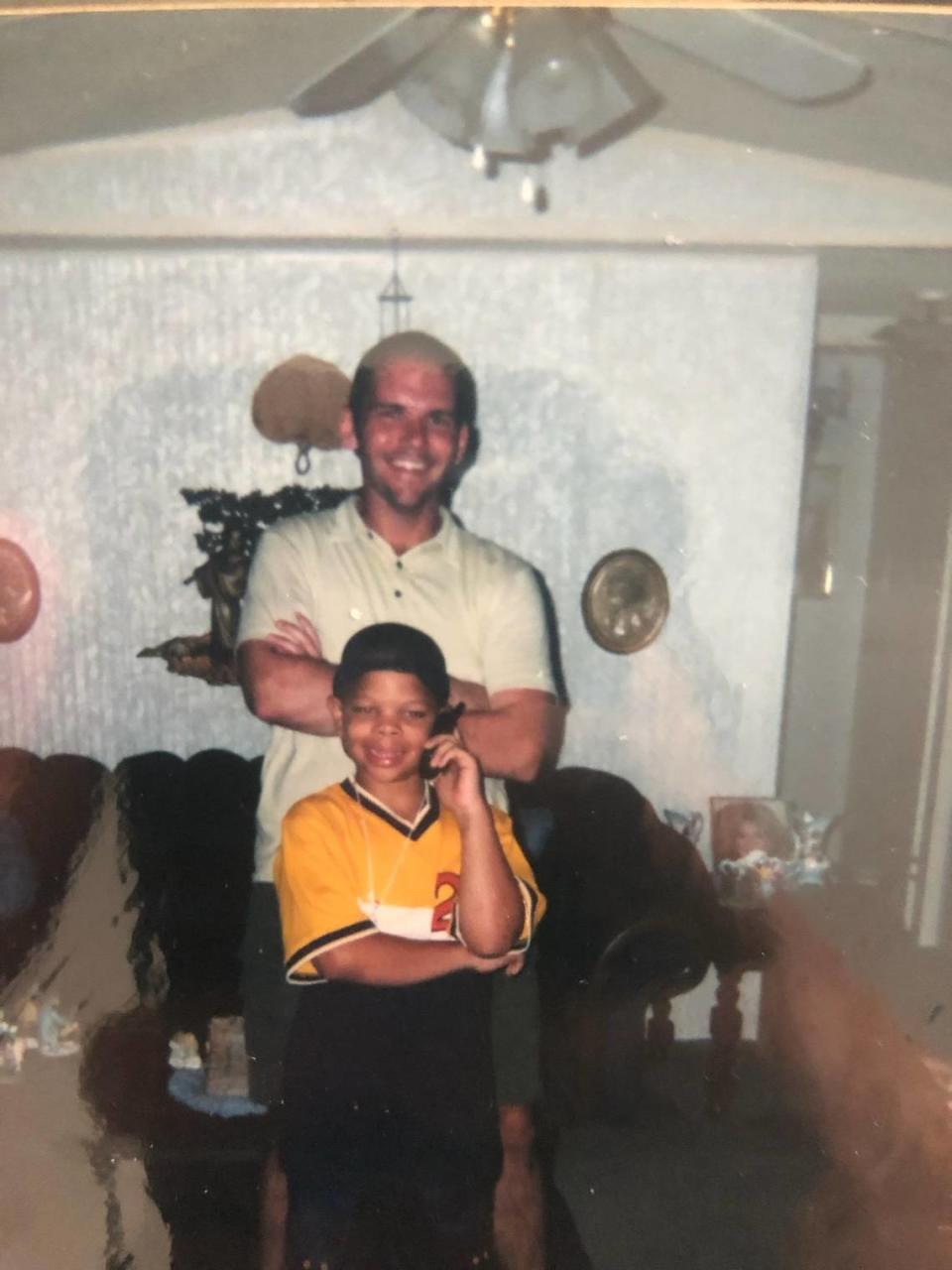

Woods is one of seven Charlotte children who lost their mothers to Wallace’s killing spree. He was 9 before he saw Henderson’s photograph for the first time.

His life, he says, has been a testament to the staying power of violence and loss. How his mother’s killing broke apart an already splintered family. How it contributed, he believes, to the death of his father. How growing up without parents was like being thrown from a moving car onto a rutted road of fleeting relationships and multiple arrests.

He learned how to survive, he says, but not how to love.

Decades removed from his mother’s death, Woods says he still suffers from abandonment issues and separation anxiety. He has never experienced the unconditional love of a mother, he says. By comparison, every relationship in his life seems to have come with quid pro quos.

He blames it all on Henry Wallace.

“What did he steal from me? That’s like a run-on sentence,” Woods says from Tampa, Fla., where he lives with his wife and three sons.

“I never had my mother’s love. There was nobody that I could go to to cry or really talk. I get the ‘tough’ part. But I never got the ‘love’ part. I really did not understand how to love until I had my own son.

“I blame Henry for that. He took everything from me.”

Woods knows he is not Wallace’s only surviving victim. But he feels driven to speak up for all the families who lost daughters, sisters, mothers and aunts. He then directs his words to Wallace, as if the killer has again appeared at the door of Woods’ home.

“You killed my mother, bro,” Woods says. “You took away so much.”

Brandi Henderson’s family

Brandi Henderson did not have many friends. One was her killer. Another was George Burrell.

Brandi and George were first cousins who shared the same birthday, five years apart. They also were best friends.

She and George saw each other almost every day, particularly after the birth of Tyrece in May 1993. Being a mother “rooted her,” George says of Brandi, and brought a greater purpose to her life.

“Brandi was young. She was small, and Tyrece’s baby stroller was more than two times bigger than her. You could barely see her behind it,” Burrell recalls.

“She would be pushing that thing up the hill toward my apartment, and I would see the baby carriage first and then Brandi’s head would pop up, and Tyrece, you know, just sitting in there. It was just the funniest thing. We would sit on the back porch talking, and Tyrece would eat hot dogs and Cheetos, and he’d have Cheetos smashed all over his face, and his mom would want to kill me.”

Burrell pauses, then speaks of little things that have become bigger things over time.

“Those memories,” he says. “That’s all I have — you know? — of him and her together.”

On the evening of March 9, 1994, between 8 and 9 p.m., Burrell got a phone call from Brandi, who lived a two-minute walk away in The Lake Apartments. She and Verness “Squeaky” Woods had moved in a month earlier to rent a bigger place for themselves and their then 9-month-old son.

Over the phone that night, Henderson repeatedly begged Burrell to drop by. Squeaky would be working until midnight, she told him; she had ordered Chinese take-out, and she had recently bought some new toys for Tyrece that she wanted George to see.

Burrell begged off, telling her that he was already too tired and had to get up early the next morning to make bread dough during his shift at the Pizza Hut on Milton Road.

The cousins went back and forth on the phone until Brandi broke in.

“Hold on,” she told Burrell. “Somebody’s at the door.”

Burrell then heard Henderson tell her visitor, “Lock the door behind you.”

Moments later, Brandi said goodnight and hung up.

“She did not have any kind of nervousness,” Burrell recalls. “It was just like somebody came to visit, who always comes. So I didn’t think twice.”

He was awakened by a phone call at dawn the next morning. It was his sister, Elisa Foster.

“I left the radio on when I fell asleep. It woke me up because I heard Brandi’s name. I heard them say Brandi was murdered last night,” he said she told him.

“There’s no way,” Burrell remembers telling his sister. “I just talked to her.”

He rushed to his TV. The first thing he saw was a video clip of Brandi’s covered body being wheeled away on a gurney.

The shock was immediate, Burrell says. Then came the waves of guilt. Would he have saved her if he had dropped by as she had asked? Or, would Brandi’s killer have killed him, too? Thirty years later, Burrell still grapples with the questions.

“If I had a chance to talk to her I’d tell her I was sorry, sorry that I did not come,” Burrell says.

“And I would ask her — I need to know this — ‘Were you calling for me? Were you hoping I would change my mind and just show up? That I could feel what was going on with you?”’

The man on the couch

That afternoon, Burrell left work early and went looking for Squeaky Woods, hoping to learn more about his cousin’s killing. He stopped at the apartment of a mutual friend named Kevin to see if Woods was there.

When Burrell walked through the front door, he recognized a man on the couch in front of Kevin’s big, new TV. The man offered to make room next to him, but Burrell found a spot on the floor to the left of the other man’s feet.

It was Henry Wallace.

The TV was on. There was not much talking. Everyone was glued to a news report on the murders the day before of Brandi and Betty Baucom, another resident of The Lake Apartments, who police believed had been raped and strangled only hours before Brandi.

During a commercial break, the man on the couch patted Burrell’s shoulder and offered his condolences.

“She was so nice,” Wallace said of Brandi. “All she did was stay at home all the time with the baby, and when someone came in and when they left, she would always lock the door behind them.”

When the news came back on, Wallace quieted the room as police detectives on the TV screen publicly acknowledged for the first time that a serial killer was targeting women in east and west Charlotte.

“We’re putting out a warning to women: Don’t let anybody into your house,” CMPD homicide investigator Rick Sanders said during the broadcast.

Burrell watched with the others. When he turned and glanced to his right, a chill shot through him. The eyes of Henry Wallace burned.

“It was like he had disappeared from where we were and he was off in his own mind,” Burrell wrote in his journal at the time.

Wallace had sold Kevin the big TV. It later occurred to Burrell that the killer had likely stolen the set from one of his victims.

Chicago

Only days after he discovered his girlfriend and his son on the floor of his apartment, Squeaky Woods left Charlotte, driving to Tampa with Tyrece to move in with relatives.

The move was so sudden that Woods left Henderson’s clothes hanging in the closet, Burrell says. It would take years for his side of the family to find Tyrece.

The father and son’s stay in Florida was brief before they moved on to Squeaky’s hometown of Chicago. There, they lived with Squeaky’s grandmother, who had an apartment in a public housing project.

Looking back, Tyrece says that Squeaky was being chased by something he could not outrun — the crushing realization that his best friend had raped and strangled his girlfriend and had almost killed his infant son.

“You see pictures before the killing, and he’d be smiling or laughing,” Tyrece says. “Every picture afterward, in every single one, he was a zombie. Just blank. Not a twitch. Not an emotion. Not a sign of his soul.”

Squeaky Woods died in his sleep when he was 28. Tyrece was 5. He still does not know many of the details, he says.

That left the boy in Chicago under the care of his great-grandmother. She taught him to cook, to clean and to garden. “She taught me how to be hard,” he says. “She taught me how to survive.”

There was no talk of his mother. No photographs of her either. “You can’t miss what you never had,” Tyrece says. “I didn’t ask questions. I just didn’t get it.”

That was about to change.

‘Country white folks’

Brandi Henderson’s mother was white. Her father was Black. The two sides of the Charlotte family did not intermingle, Burrell says. Brandi navigated each separately.

When Tyrece was 7, a mini-van pulled up in front of his apartment building in inner city Chicago. A group of white people — “country white folks in the middle of the freakin’ ghetto” as Tyrece describes them now — climbed out. Six years after his father had taken him away from Charlotte, the white side of his mother’s family had tracked him down.

After a 12-hour drive, they stayed for less than a day. After lunch, they took Tyrece for ice cream, and visited parks and sites along the “Magnificent Mile” near the lakefront in north Chicago that the boy had never seen.

Two years later, Tyrece took his first airplane trip, from Chicago to Charlotte. Over the next week, he would finally get to know more about his mother.

Burrell and the boy’s other Charlotte relatives “filled in the gaps of what happened. I never had an understanding,” Woods says. “George took me everywhere — to my mom’s grave, where she lived. How she died.

“They told me that she loved me, that she fought for me, that she had a big heart. They told me I was special because I wasn’t supposed to be there, that I almost didn’t make it.”

On a Sunday, Burrell also took Tyrece to his mother’s church, Macedonia Baptist, where as an infant Woods had been kept by relatives in the back of the sanctuary during Brandi’s funeral. Toward the end of the service, he was brought to the white casket to see his mother for a final time. She wore a pink dress.

Now, eight years later, the pastor asked Tyrece to stand. He introduced the boy to the congregation as “Brandi’s son,” the child who had miraculously survived the clutches of a killer.

“The whole church went crazy,” Woods says. “I felt like a superstar. Everybody hugging me. A bunch of love I’d never felt before because I didn’t have a mother. I loved North Carolina.”

Woods also learned to swim on the trip, spending much of his free time in the pool outside of Burrell’s apartment. Last year, after he learned that his mother had been a fine swimmer, Woods had a conversation with her inside his head — from the perspective of a little boy left on his own but with a mother somehow looking out for him.

“Mommy’s going to make sure you’re safe. Mommy’s not going to let you drown,” Woods says he told himself. “This whole life is like a big ocean, and Mommy’s not going to let you go under.”

‘I’m not healed’

Almost 20 years would pass before Woods and Burrell would next see each other. Once again it was in Charlotte.

The adult Tyrece, according to his cousin, seemed “worn, like he was carrying a lot of heavy things, that he had been through a lot.”

When he was 12, his great-grandmother, who Woods had taken care of since he was in elementary school, left him with relatives in Florida whom Woods says he barely knew.

His life took a downward slide. He began to be overwhelmed with anger and frustration, he says. He had trouble following rules. He was tired of always needing money. A series of “dumb decisions and poor choices” followed.

At 16, he says, he went to prison for 18 months on burglary and robbery charges. Other arrests followed, the last for drug and weapons violations some five years ago.

Today, almost three decades removed from his mother’s murder, Woods says he’s working hard to put his mistakes behind him. He’s trying to be a good husband and father, he says, hoping to teach his sons — Eric, 12, Jordan, 10, and Lucas, 7 — how to both love and to be strong.

He has a clothing line, “Hyena Zone,” that he started in 2020 and hopes to market to adults and children alike.

“You’re here for a reason. You’re a hyena!!!,” Woods’ web page blares with all-caps bravado. “Hyenas are survivors just like me. Let me show you how I managed being a serial killer survivor. Come into Hyena Zone knowing that, even through the struggles of life, you too can survive.”

The brand’s name parallels his own life, Woods says. How the hyena pack is run by females, how “Young male hyenas get kicked out of the clan ... and have to start at the bottom,” he says.

“I try to keep going, try to keep elevating. But I fall all the time. It’s important for me not to be messing up any more, me not making the same mistakes. I don’t want to continue, continue, continue to go through the same trial and error.”

Woods says he often thinks of his mother, and still envisions a life that would make her proud, particularly in how he treats his children.

“I’m trying to make sure I can be the best father I can be because I know she would have been the best mother,” he says.

When and if Henry Wallace is executed for his crimes, Woods says he intends to be on hand to watch him die. Asked what he would say to Wallace if given the chance, he replies, “I might tell him I’m not healed.”

“I can’t wait to see him face to face when he knows it’s time for him to go. I want to look him in the eyes and let him know that, yeah, ‘I’m still here. I’m still here. You can’t take my breath. You can’t take my breath.’

“... He took the breath out of my mother’s body. I don’t think he and I should be sharing the same air in this world.

“One of us needs to go.”