After several relatives died of fentanyl overdoses, Topekan fights for good Samaritan law

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Kansas is one of only two states without a good Samaritan law, which shields people who call 911 during an overdose of criminal charges.

The state’s overdose mortality rate is the 13th lowest in the country, but it is rising.

Kansas’s overdose death to a new high of 738 in 2022. The increase is largely driving by synthetic opioids, which claimed 497 lives.

In response to the crisis, the legislature joined more than 20 other states when it legalized fentanyl test strips during the 2023 session.

One of the Kansans lost to opioids was Kaylee Burger, who passed away at 22 after smoking fentanyl-laced methamphetamine. She was the fourth person in her family who passed away from fentanyl.

The first occurred two years ago when Burger’s once-removed cousin, Kassie Montoya, overdosed on illicit pressed pills containing fentanyl in October 2021. Next, her 16-year-old brother-in-law David Carr Jr. passed away in July 2022, also from counterfeit pills. Her aunt Monica Burger died of a fentanyl overdose two months later.

Burger’s stepmother Amber Saale-Burger remembers Burger as someone who was always willing and able to help those around her. Saale-Burger said Burger was excited to sign up for organ donation and the prospect of saving another person. Her decision saved five lives.

“She was able to help five people with that. But we wanted to continue to help as much as possible, because that’s all she ever wanted to do,” said Saale-Burger, who moved to Topeka two years ago. “That’s why we’ve kind of carried her torch. We’ve picked it up and we’re not going to put it down.”

Daughter's death from fentanyl-laced methamphetamine drives effort

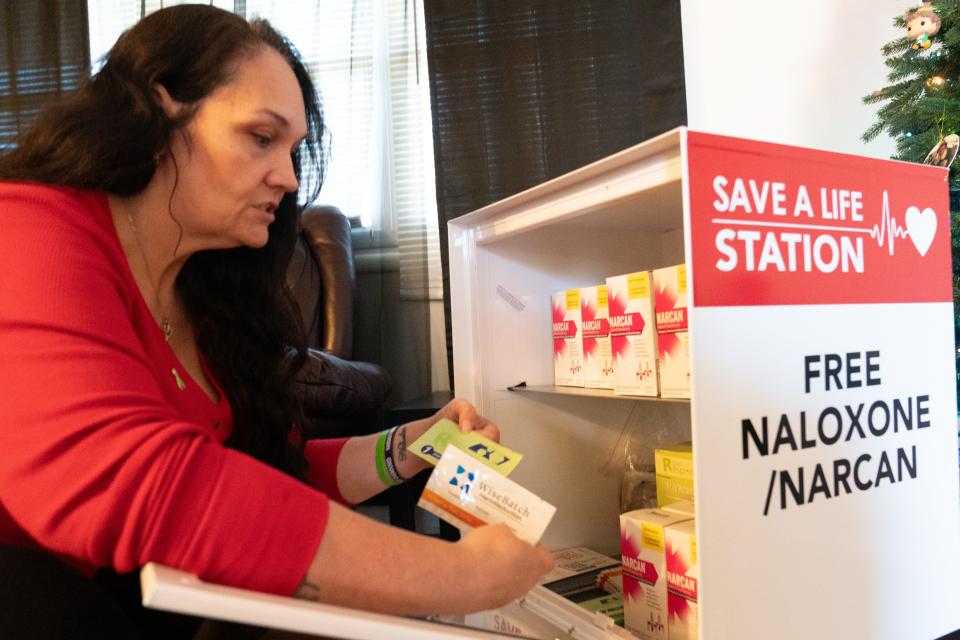

Saale-Burger became involved in several different projects a couple months after the death of her daughter. She procured a Save-a-Life Station, a box containing fentanyl test strips, information about rehabilitation services and naloxone, a drug that reverses opioid overdoses.

She’s fundraising on GoFundMe to buy more stations and re-supply her existing one.

She also started contacting local legislators to advocate for a good Samaritan law.

“I know that with my son-in-law and my sister-in-law, had this law been in place, and those people knew that they weren’t going to jail, they would have gotten 911 there quicker," Saale-Burger said. "And I honestly feel like they’d still be here if we had that law.”

Kansas Rep. Pat Proctor, R-Leavenworth, plans to introduce legislation to create a good Samaritan law. The bill has a Democratic co-sponsor with Rep. John Alcala, D-Topeka. Proctor said he’s heard from many people who lost family members and friends to the drug.

“A common theme with a lot of the stories is that their family member was in the presence of other people who were afraid to call authorities because they’re afraid they would get arrested themselves,” Proctor said.

Rep. Nick Hoheisel, R-Wichita, is also working on a version of the good Samaritan law. His working version includes a stipulation that protections don’t apply to situations involving a trafficable amount of drugs on site.

“Mine just basically covers simple possession of drugs, as well as paraphernalia,” Hoheisel said.

Both groups said their vision now may differ from what’s ultimately introduced, and they may combine their efforts to introduce the bill. Hoheisel said he’s basing his version on Oklahoma’s good Samaritan law, while Proctor is using Iowa as a template.

Both states require whoever reports an overdose to give accurate information about themselves and to stay on scene until help comes.

Kansas is seeing the third wave of the opioid epidemic

Illicit fentanyl is often considered the third wave of the opioid crisis in America. The first wave started in 1999 with a rise in deaths from such prescription opioids as oxycodone and hydrocodone. In 2010, the second wave began, in which overdoses from heroin use rose.

By 2013, illicitly manufactured synthetic opioids became more prevalent and now constitute a majority of opioid overdose deaths. Between 1999 and 2021, more than 645,000 people died from an opioid overdose, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Fentanyl differs from other opioids in its potency. The Drug Enforcement Agency says the drug is 100 times stronger than morphine, and that as little as 2 milligrams can be fatal.

“The fact that it’s so unpredictably manufactured, you don’t get consistent dosages of it, and it’s so lethal in small doses is what contributes to the number of deaths we’re seeing,” said Kansas Bureau of Investigation director Tony Mattivi.

KBI’s Joint Fentanyl Impact Team, along with other partnering law enforcement agencies, on Nov. 29 seized 60,000 fentanyl pills, 4 pounds of fentanyl powder and 59 pounds of methamphetamine. The task force formed in July between the KBI and Kansas Highway Patrol to disrupt fentanyl trafficking networks across the state.

Mattivi didn’t comment on good Samaritan laws but said users can be the first point of contact in an investigation. He noted, however, that the task force isn’t focused on drug users.

“We’re looking for suppliers. Sometimes the way we find those suppliers is we find a user who has overdosed, for example, and we may try to get information from that user about who were their suppliers,” Mattivi said. “We’re not really in the business of running around chasing drug users.”

Harm-reduction efforts involve giving people another chance

Fentanyl is often pressed to look like generic prescription oxycodone pills, but since its introduction to the U.S. market, it has been found in counterfeit versions of such other pills as Adderall and benzodiazepines. It’s also been found in such illegal drugs as cocaine, meth and even marijuana.

“We know exactly what the cartels are thinking," Mattivi said. "Fentanyl is showing up in other drugs because they want to addict as many people to it as they possibly can.”

The proliferation of cross-contaminated drugs pushed the Kansas Legislature to pass a law legalizing fentanyl test strips last year. The distribution of fentanyl test strips and good Samaritan laws are practices that are under the umbrella of harm reduction.

“We know that people that are using substances or are suffering from a substance use disorder are going to continue to use,” said Mandy Czechanski, executive director of Prevention and Resiliency Services in Topeka. “But if we can put tools in their hands that may prevent them from dying or may give them another chance at life the next day and they decide that’s the day they go into a program and try to work towards recovery, then that is a good tool to use.”

Kansas’s approval of test strips last year was the second opioid-related harm reduction policy approved by the state, after the decriminalization of naloxone in 2018. Harm reduction policies are sometimes criticized as enabling drug use, but the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration says the practice is proven to prevent death, injury, disease, overdose and substance misuse.

“We have to move the conversation of addiction to a health issue, a mental health issue, a trauma issue and a public health issue, and move it away from these moral judgement issues that they’ve been wrapped up in for a very long time,” said Rep. Jason Probst, D-Hutchison, who pushed for fentanyl test strip legalization for years.

Kansas legislative session could see introduction of good Samaritan law

With bipartisan support, the legislators working on good Samaritan laws said they’re optimistic about the bill becoming law.

“This is something that’s affecting all communities. This isn’t just a Wichita problem," Hoheisel said. "All of Kansas is seeing this problem. If we’re going to be pro-life, we need to be pro-life for these folks as well.”

For Saale-Burger, a good Samaritan law is helpful but isn't enough to end the wave of opioid deaths. Beyond her work procuring harm reduction supplies and contacting legislators, she’s also seeking to do public speaking engagements.

Saale-Burger and her husband, Max Burger, are state directors of the nonprofit Fentanyl Fathers. They are working to go to schools to raise awareness about the dangers of fentanyl.

“I’m going to push full force until someone hears me,” Saale-Burger said. “It’s either get on board or get out of the way because I’ve got some kids to help save.”

This article originally appeared on Topeka Capital-Journal: Topekan urges good Samaritan law after losing daughter to fentanyl