Sex trafficking sentence overturned after ‘racial misconduct’ by Tri-Cities prosecutor

A Tri-Cities gang leader will be allowed to withdraw his guilty plea for sex trafficking, which came with a sentence of 25 years, after an appeals court found “race-based prosecutorial misconduct.”

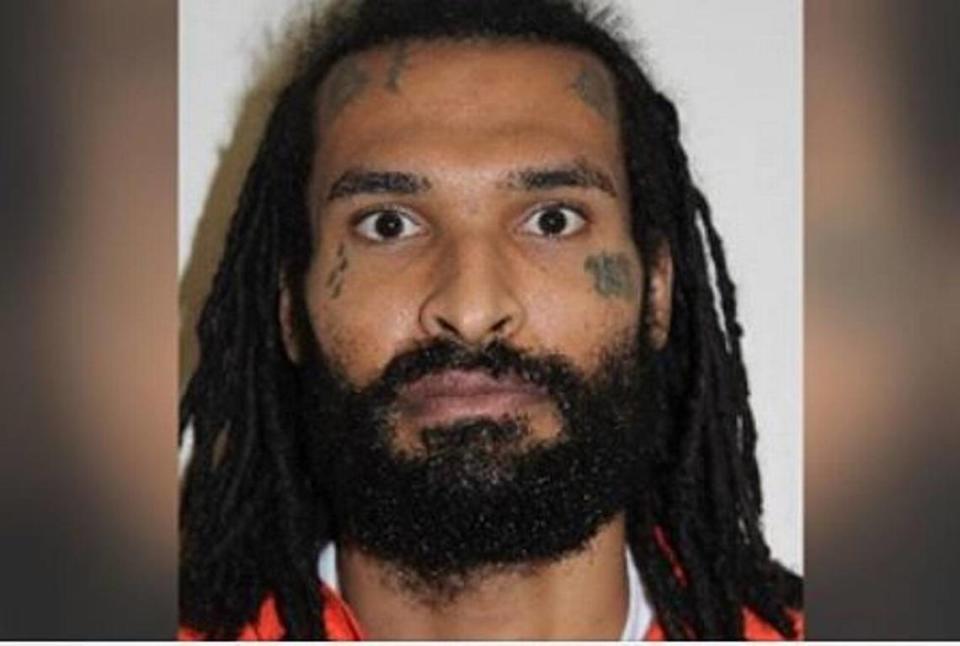

In May 2022, Lance Ray Horntvedt Sr., now 37, pleaded guilty in Franklin County Superior Court to one count of first-degree sex trafficking and five counts of second-degree sex trafficking from 2015 to 2018.

The 6-foot-8 former professional fighter was accused of threats and violence against women he allegedly trafficked for sex.

He was offered a plea deal of 25 years in prison, rather than the 66 years he could have faced if he had gone to trial and been found guilty. He first tried to take back his guilty plea in 2021, but it was denied by Superior Court Judge Alex Ekstrom.

Under the agreement he also would be required to register as a sex offender and be barred for 50 years from any contact with the women.

At the time Horntvedt, who is Black, argued his guilty plea was not voluntary because he was told that a jury who heard the case would likely be mostly White even if the trial was moved to another county. And he said his grandmother had asserted undue influence to persuade him to accept a plea deal.

New court documents show that the Washington state Division 3 Court of Appeals agreed he can withdraw his plea and could take his case to a jury.

In a statement to the Herald, the Franklin County Prosecutor’s office said that they are “disappointed with the Court of Appeals’ decision and would note that no malice was found by the Court.”

They were unable to offer further comment due to rules governing professional conduct of prosecutors preventing them from making statements on cases the office is currently engaged in.

Race based prosecutor misconduct

During a plea negotiation meeting in March 2021, Deputy Prosecutor Maureen Astley made comments that the Appeals Court found crossed the line into racial bias, according to the decision written by Judge Lawrence Berry.

The 2021 meeting included Astley, another deputy prosecutor and a defense attorney, who are White, and Horntvedt.

At the meeting Astley said she was not trying to intimidate or scare Horntvedt but making him aware of what he could face if he went to trial, according to court documents.

She first explained that only five of the seven Superior Court judges could take the case due to other conflicts, and two of them were women, which “which might be difficult for you in a case like this where there are six women victims . . . but those are things for you to consider as well.”

She then told Horntvedt that he would likely get a White jury, according to a partial transcript included in the court documents.

“The jury is picked from (Department of Licensing) records as well as voting records. So the jury that you will get will not necessarily be a jury of your peers, but it’ll be a jury of our peers, be a lot of White folks. And I’m not saying that . . . to scare you. That’s reality. We have very few . . . jurors of color that show up or . . . respond to our jury summons. That’s just the way it is in Franklin County. . . . But I just want you to know that, and I’m telling you that straight away so you’re clear on that.”

According to witnesses, when Astley said “your peers,” she gestured her hand toward Mr. Horntvedt, and when she said “our peers” she gestured toward herself and the defense counsel.

Horntvedt’s lawyer also discussed his request for a change of venue to another county. He said that the most likely scenario was a move to either Walla Walla or Yakima counties, which could be bad for Horntvedt because “Walla Walla is more Caucasian than the Tri-Cities,” and he wasn’t sure what a jury would look like in Yakima.

As they were leaving the meeting, Horntvedt remarked to a jailer, “That’s some racist s--t, right there.”

Afterward the defense attorney told Astley that Horntvedt was upset about her comments.

She responded that she was just trying to make him aware that jury panels in the Tri-Cities may not be racially diverse or representative of the community as a whole.

“You have shared that your client was upset at my comment about the makeup of Franklin County juries. Please understand that I shared that solely to make him aware of the fact that, on the whole, our jury panels are not racially diverse and are unfortunately not usually representative of our community in total,” she wrote.

“This comment was based on my experience of trying nearly 60 jury trials here throughout my career. Nothing was meant to imply that we would be unable to seat a fair jury in Franklin County, as it is of course my ethical obligation (and yours) to endeavor to pick jurors who are fair and impartial and free of bias . . . I just did not want him to reject the offer and then be surprised with the composition of our typical jury pools. “

At his June 2021 sentencing, Horntvedt’s attorney asked the judge if they could play a portion of the recording from that meeting, in order to have the judge determine whether or not Horntvedt had been coerced to plead guilty.

His attorney said Horntvedt was struggling with whether or not to request having his plea withdrawn, and they thought it would be best to have the judge listen to the conversation and advise.

The judge asked a few questions about the recording, but ultimately did not allow it to be played and told the defense attorney that they had a choice to adhere to the plea or try to withdraw it.

Attempt to withdraw plea

Horntvedt and his attorney decided to move forward with an official attempt to withdraw the guilty plea. At an hearing a few weeks later, Astley testified about the purpose of her comments and the court also entered into evidence the letter she had written to the defense attorney.

“My purpose was kind of two fold: Mr. Horntvedt, I’ve prosecuted him a couple times before. He’s never had a case that has gone to a jury trial. So I wanted to kind of let him know a little of what to expect. Sometimes people’s expectations of what a jury pool will look like or will be is not the reality. ...“

“Secondly, I’ve had cases before where a defendant comes into court and sees a jury pool, and it’s not what they expect, and then they want to change their mind at the last minute. So I was telegraphing to him that we get the jury pool that we get.”

Horntvedt testified that he was shocked by the remarks and felt like he was being attacked. He said he told his defense attorney he felt the comments were racist and wanted to be able to present them to the court.

The judge agreed Astley’s comments were “improper” but that Horntvedt’s plea was “knowing, voluntary, and intelligent” and went ahead with his sentencing.

Manifest injustice

The Appeals Court wrote that a judge must allow a defendant to withdraw a plea when a “manifest injustice” is found to have occurred. A manifest injustice can occur when a plea is made involuntarily, it said.

“(B)ased on an objective review, we conclude the prosecutor’s invocation of race to leverage a guilty plea rendered the plea involuntary as a matter of law ... Reliance on racial or ethnic bias has no place in the justice system,” said the higher court.

Judge Berry wrote that appeals to bias harm the institution of justice as a whole. He referred to State V. Bagby, a Whitman County case in which prosecutors were found to have appealed to jurors’ racial bias when repeatedly asking about a Black defendant’s nationality, despite him being an American citizen, according to the Spokesman-Review.

“Appeals to bias not only cause personal harm and undermine the integrity of the judicial system, they distort the deliberative process. ‘Even the simplest racial cues can trigger implicit biases . . . (that) affect . . . decision-making more so than even explicit references to race.’”

The Appeals Court wrote that the standard for determining if a judgment has been wrongly affected by racism was set by the Supreme Court and guides the court to resist speculating about the exact impact and ask if an objective observer could view the prosecution’s comments as an appeal to prejudice, bias or stereotypes.

The court determined that an objective observer could view Astley’s comments as an appeal to bias based on her comments about Horntvedt not receiving a jury of “his” peers and describing the anticipated jurors as “white folk.”

“An objective observer could construe the prosecutor’s comments as leveraging the possibility of racial bias in order to secure Mr. Horntvedt’s guilty plea. The prosecutor’s statement was not merely an innocuous comment on the realities of Franklin County’s jury pools. An objective observer could fairly understand the comments to mean that Mr. Horntvedt’s chances for a fair trial in Franklin County would turn on his race, as opposed to the strength of the evidence. Because Mr. Horntvedt is African American, the message was clear that he would be less likely to receive a fair trial than a white defendant.”

The court said this message of unfairness was underscored by “implying his case might also be made ‘difficult’ by the possible involvement of a female judge.”

The court said that while the comments were apparently an intentional plea to racial bias, that does not mean they were guided by animus, and that they may have been well intentioned with Horntvedt’s best interests in mind.

The court wrote that the “objective observer” is not concerned with the intent or speculative damage, but rather the impact of racial bias on a defendant or the court.

With that in mind, the Appeals Court wrote that their review of the record shows the prosecutor appealed to fears of racial bias in order to leverage Horntvedt’s guilty plea.

The court ruled that Horntvedt must be given the option to withdraw his guilty plea and allowed to go to trial if he does.

“All members of the legal community — law enforcement, attorneys and judges — bear responsibility for addressing racial inequities in our justice system. This is hard work. None of us has all the answers and all of us will sometimes get things wrong. Yet we must move forward with humility, compassion, and dedication to constant improvement.”

Sex trafficking allegations

Investigators claim in court documents that Horntvedt was the leader of the Gangster Disciples.

Officials say he took a 19-year-old from Utah to Washington state without her family’s knowledge and then hid her. He told her she would go on “dates” but sex would not be involved.

However, a day after arriving in Washington she was coerced into sex with Horntvedt’s heroin dealer for money after she heard Horntvedt threaten two other women, according to court documents. She feared Horntvedt would hurt them if she did not do what Horntvedt demanded.

The teen begged to return to Utah, but Horntvedt refused and he took her iPad, cellphone and clothes, she said. She was in Washington for three weeks before she was able to contact her parents, who sent her a bus ticket.

In another instance, he recruited a woman in her early 30s to provide paid sex. He frequently assaulted her in front of others and threatened her to make her continue working for him, according to court documents.

Witnessing those assaults, another woman in her early 40s continued to provide sex for money, said officials.

According to court documents, Horntvedt recruited her into his sex trafficking operation by telling her she would make lots of money but then he took all the money she was paid. He also forced one woman to sign over her car title to him, according to documents.

He told a woman in her early 30s that if she tried to leave he would find her. And he told a woman in her early 20s that “if people were really telling on me they wouldn’t be breathing anymore,” according to court documents.

Horntvedt has since been in further trouble for his alleged involvement in a smuggling ring with jailers, who brought meth, heroin, cell phones and more into the Benton County jail.

Annette Cary contributed to this report.