'This was sexual assault': Lack of consent law leaves survivors without justice in South Dakota

Editor's note: This story features descriptions of sexual assault.

When Penny saw someone get off the Sioux Area Metro bus, she jumped. It didn't matter who it was, because in her mind, it could be her attacker.

She doesn’t have a car, so she relies on public transportation, and Penny's constant state of alert is so bad even her daughter has noticed.

"She never really looked over her shoulder, now she does," her daughter said. "She's more jumpy."

On the west side of Sioux Falls earlier this spring, the panic crept up Penny's spine. Her hands started to shake as she walked down the street toward her job as a life skill educator at a treatment facility.

“I'm afraid to go to work, because that's where he used to live. That whole area, I'm always looking over my shoulder,” Penny, 54, said.

Penny says she was sexually assaulted at the end of July 2021, but she wasn’t sure if it rose to the level of rape. She never said yes, but she also never said no.

She froze, unable to give consent, unable to fight back and unsure that if she did, she would leave the room alive.

Her attacker was not charged.

That’s because in South Dakota law, there is no definition of “consent.” Therefore, if someone is sexually assaulted, it becomes incredibly difficult to establish means to prosecute.

As part of an ongoing Argus Leader investigation into how the state handles sex crimes under the law, the lack of a consent law leaves survivors like Penny falling into the cracks. Some cases have gone to trial, but survivors don’t always get the justice they seek, especially if their case doesn't have enough evidence to even make it to trial. That doesn't include survivors who choose not to come forward about their assault.

"I've had to call people in and say, 'I am really sorry, but I can't charge this out,'" said Lori Ehlers, a senior prosecutor in the Minnehaha County state's attorney's office.

Efforts to create a consent statute have failed twice in the state legislature. But without one, survivors continue to watch as an imperfect justice system lets their attackers go, while they continue to live with the trauma and fear.

The gravity of the incident didn't click with Penny until days later after speaking with friends.

The Argus Leader typically does not name survivors of sexual assault out of protection for their safety and the possibility of re-traumatization. Penny, however, gave the Argus permission to use her first name only.

After she filed a police report, she was told by a detective her case had a “lack of merit” and could not be prosecuted.

"I don't think there should be a middleman, because you can't see fear on a piece of paper," Penny said about how dogged she had to be to even get her story in front of a prosecutor. "As I sit here now I can feel it. They need to see fear so they understand that this was real."

What do we mean when we talk about consent?

Consent is the action of saying yes to a sexual activity, according to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN). It should be freely given, meaning the person shouldn’t be under the influence of alcohol or a substance, or feel threatened or intimidated.

Twenty-six states, including South Dakota, do not have clear consent laws on the books, according to RAINN. The closest South Dakota gets is second-degree rape, or forcible rape, and third-degree rape, which includes being incapable of consent due to intoxication.

But if a survivor freezes and can't fight back, like Penny, there's no statute for them.

“There's been times that come up in cases, where consent is not defined anywhere in statutes, and so it has created some concerns during prosecution,” said Krista Heeren-Graber, the executive director of the South Dakota Network Against Family Violence and Sexual Assault.

More: The Link will offer sexual assault kits starting in early May

But Heeren-Graber said there’s a bigger societal issue at hand: myths surrounding the definition of consent, when survivors don’t fight back and what consent actually looks like.

States like California and Minnesota have created statutes called “affirmative consent laws,” which means there should be verbal and expressive consent as a way to combat these myths.

“More than the absence of a no and the presence of a yes, the yes needs to be engaged, excited and active,” Christine Emba wrote about affirmative consent in her recent book “Rethinking Sex,” an exploration into American society’s views of sex. “This approach tries to distinguish between wanted and unwanted sex, even though both might conceivably be 'consented' to, and attempts to encompass both agency and desire.”

Craving safety and security, she missed the red flags — at

Penny first met "The Boy" in April 2021, when she was working as a cashier at a Sioux Falls casino.

“He walked in and caught my attention, because he was cute and had lots of hair,” she said.

Penny refers to him as "The Boy," because after the assault, he was no longer a 44-year-old man in her eyes and she didn’t want to use his name anymore.

The Argus Leader will also not use his name because he was not arrested or charged.

The two started hanging out, staying up late, getting to know one another. He would walk her home from work when her shifts ended at 2 a.m., she said.

“He used to ask me, ‘Why do you like me?’ And I'd say, ‘Because you make me feel safe. You make me laugh and you never told me to shut up,’” Penny said, recalling she craved safety and security after a series of abusive relationships.

Penny described her relationship with "The Boy" as an emotional attachment. The two rarely had sex.

Penny didn’t notice red flags until June, when "The Boy" started drinking more. He became physically violent, grabbing and shaking her. His language toward her became more gruffer and more demanding, she said.

One night, he got drunk and threatened to take a large dose of Penny's anxiety medicine, she said. He passed out in her house and she called the police, unsure of what might happen when he woke up.

That night she filed a temporary protection order against him, according to court documents, and on her daughter’s advice. He would no longer be able to visit Penny at her apartment. But Penny continued to see him at his apartment.

“I tried to keep it a secret, because I was embarrassed,” she said. “The fear was starting to come, but I think at that point, it was too late. I was already into him. It was like I had to be around him.”

A month later on July 25, Penny made the 20-minute walk from her home to "The Boy’s" apartment. They spent the night talking and listening to the radio. In the morning, "The Boy" gruffly told Penny it was her turn to make breakfast, but as she stood at the microwave, “the next thing I know, someone’s grabbing my shirt and he threw me to the side and I almost fell.”

She tried to head toward the door to leave, but he grabbed her and threw her again, she said.

“Next thing I know, he’s got me laid on his bed and I just froze the rest of the time,” she said.

Penny said the assault lasted 20 minutes. She alleges "The Boy" bit her forcefully, digitally penetrated her and forced her to masturbate until her body naturally reacted before he would let her go.

"I was just baffled that I wasn't getting out of there," Penny said as she described where her mind went during the assault. "I remember thinking to myself, 'One: I got to get up and get away from him, and two: why am I laying here, and my body is having an orgasm?'"

A common rape myth circles around if the survivor had an orgasm, then it couldn't fall under rape, according to the Cleveland Rape Crisis Center. However, an orgasm is a physical reaction that cannot be controlled, whether or not someone has consented to a sexual act.

She left the apartment before 10 a.m., still dressed in the red Nebraska shirt and shorts she’d worn the night before, and went about her day, she said.

While the assault is crystal clear in her mind, she can’t remember exactly how many days it took her to file a police report, but she knows it took about a week, she said.

Penny walked into the Law Enforcement Center in Sioux Falls at the beginning of August to file her report.

Sioux Falls police confirmed to the Argus Leader that Penny made a report. Since filing that report, Penny’s been in limbo.

‘Lack of prosecutorial evidence’

When someone comes into the police department saying they’ve been sexually assaulted, the first step is to understand how the survivor wants to proceed, said Sgt. Robert Forster, a supervisor on the crimes against persons squad at the Sioux Falls Police Department.

“The most important thing that we keep in mind is that our victim steers the investigation ultimately in these cases, because these are very private, traumatic events for a victim,” he said.

If the police report is made within 96 hours of the assault, especially if it’s a rape, officers are tasked with trying to preserve as much evidence as possible, Forster explained. Sometimes, survivors are already at the hospital where a sexual assault nurse examiner takes swabs for evidence. Other times, if survivors go to the police first, they’re asked if they would like to go to the hospital.

“We want to try to get some forensic evidence, we can help that victim out in the long run if we do end up going to court for any type of prosecution against a perpetrator,” Forster explained.

Officers also take the survivor's statement and start the investigation process, which sometimes takes months, depending on if the survivor wants to press charges right away or if they want to take a step back and heal a bit first before retelling their story, Forster said.

In 2021, the SFPD has investigated 577 cases related to sex crimes, such as sexual contact, sex offender violations and cases not amounting to rape. Of those cases, 119 were rape cases.

In Penny’s case, she did not go to a hospital. When she filed her report on Aug. 2, a detective met with her minutes after she walked in that afternoon. They took photos of the bite marks she still had on her leg from "The Boy."

She’d also taken her own photos and had them printed out for when she met with the detective on her case.

Forster says anytime a survivor can bring in their own evidence, from photos to screenshots of messages and social media posts, it helps.

“Anything we can use as part of our investigation will assist us and the victim down the road,” he said. “We can’t guarantee that’s going to be something absolutely 100% solid, because we don’t know that in police work.”

But even the photos didn’t help Penny. She was told in November by a prosecutor in the state's attorney's office that because there was a lack of evidence, the case lacked merit and couldn't go forward, she said, pulling out notes she had taken from the call.

It’s not up to the police if cases will go in front of a judge, Forster said.

“We don't make those decisions on whether there's prosecutorial merit or charges are filed,” he said. “That's all on the State's Attorney's Office and the prosecutors who are elected by the public. So, those are tough decisions for them to make.”

Without formal and public recognition of her sexual assault, Penny is left wondering.

“I do still struggle with is it rape or not. All I know is that man hurt me, and I was scared to death, and I could not move," Penny told the Argus Leader, her voice shaking in anger during a sunny day at her home in April. "And even though there was no semen or (penile) penetration, he took something from me that I will never get back."

What makes a rape case go to trial in South Dakota?

There are times that certain rape cases, such as "he said, she said" cases, do go to court. Sometimes, those cases have hard evidence, such as DNA. Other times, prosecutors are able to build their cases off of corroboration.

"It can be difficult when you're talking about rape cases, because typically there's only two people in that room: that perpetrator and that victim," said Minnehaha State's Attorney Daniel Haggar. "More often than not, we have to look and say, 'What are the facts of the case?'"

Most of the time, prosecutors rely on the law enforcement investigation to find witnesses and surveillance tapes to corroborate the victim statement, Ehlers said.

"Probably more than 75% of my cases don't have DNA," she said.

In 2021, 74 rape cases out of those 119 cases from the police department, from first-degree rape through fourth-degree rape, were charged out by the Minnehaha State's Attorney's Office. The year before that it was 67 cases.

More: Here's how South Dakota law defines sex crimes and categorizes offenders

But not all went to trial, Haggar said. Some would have resulted in plea agreements, some potentially dismissals, he said.

"There's more honestly probably still pending," he said.

There have been high-profile cases of rape in Sioux Falls, most recently in 2019.

In that case, the survivor, who did not consent to the sexual act, went in front of a Minnehaha County judge. The charges against the defendant included two counts of third-degree rape and two counts of sexual assault.

The defendant was acquitted by a jury of the rape charges and one count of sexual contact with a person incapable of consenting. He was found guilty of the one count of sexual contact without consent with a person capable of consenting.

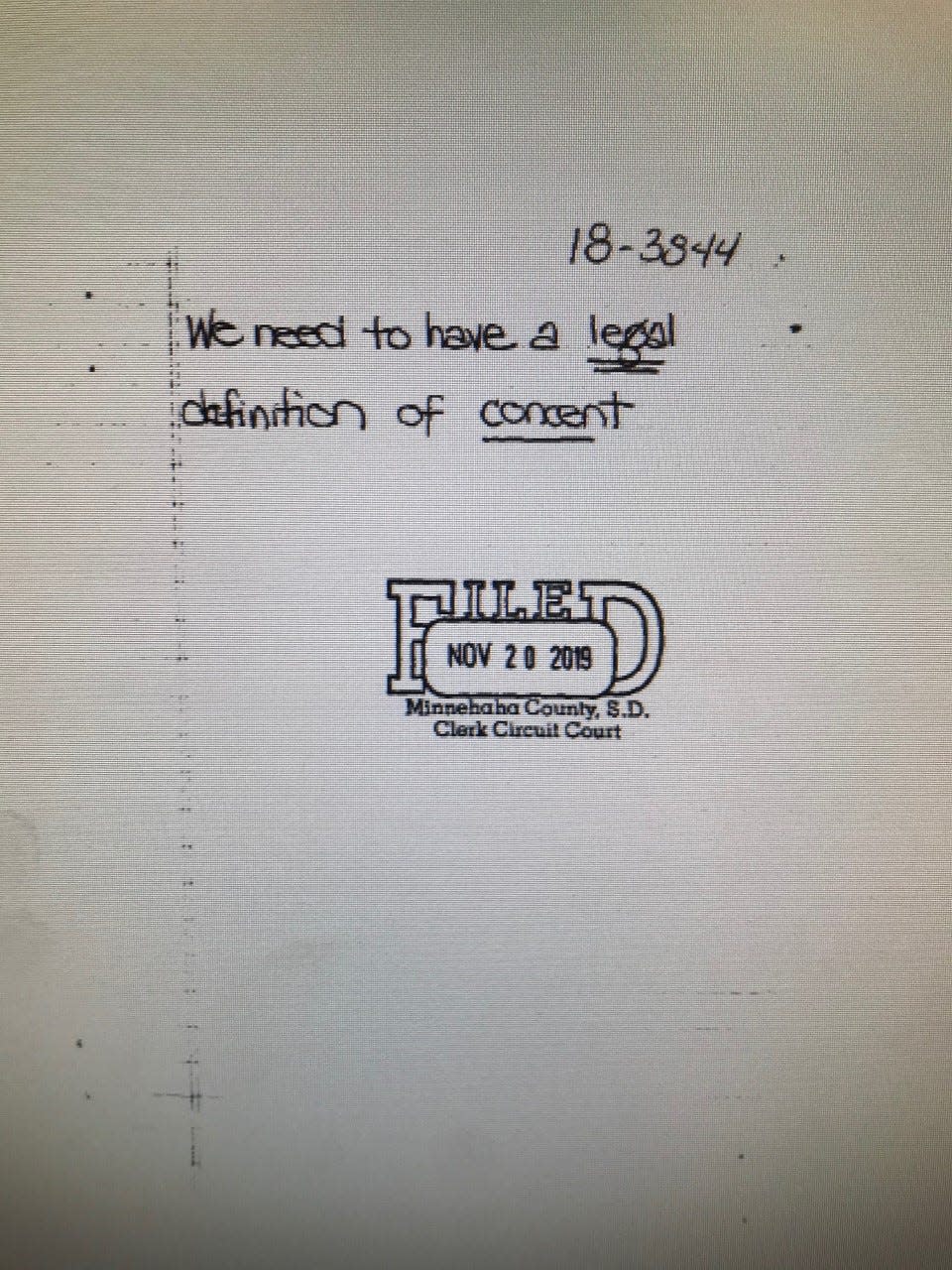

At the time, the jury had to send a note to the judge saying “we need to have a legal definition of consent.” He responded by saying the court had given them all the instructions that were needed, according to Argus reporting at the time.

The defendant had previously been charged with sexual contact without consent and served 90 days in jail nearly 10 years earlier, according to court records. He'd also been accused of having sex with a woman who was intoxicated and didn't remember inviting him over in 2017. He was not charged in that case.

Legislative fails on consent laws

Since the time that the 2019 Minnehaha County rape case was prosecuted, state Rep. Tim Reed, Brookings-R, has brought two bills forward in the state legislature that would create a definition of consent.

“That case was a driver,” he explained, one snowy March morning from his office in Brookings after the end of the 2022 legislative session.

Reed, who’s been in the legislature for six years and served five of those years on the House Judiciary committee, said that he’s worked closely with Heeren-Graber and The Network on issues relating to sexual assault.

“We just would start to discuss, are there other issues? Are there places that we need our laws changed to benefit the victims?” he said, referring to summer meetings he would have with The Network and other stakeholders.

Consent has been discussed by the group even before Reed wrote the first bill for the consent statute in 2021.

“It takes a while to make sure that you're getting a good bill when it comes to bills like this. So they can kind of percolate for a little while to make sure we're getting the right information,” he said, adding the group pulled from other state statutes when crafting the initial 2021 bill.

The first bill failed because of too many definitions about what was considered intoxicated and what was considered the ability to consent, he explained.

A year later, Reed struck those definitions and wrote House Bill 1287, which focused on the “concept of sex without consent.”

In its draft form, the bill added fifth-degree rape with a penalty of a class 4 felony, which would have had a maximum penalty of 10 years in prison. It also would’ve added a new selection to the law defining consent, “a person’s positive cooperation in an act or attitude pursuant to the person’s exercise of free well,” as well as defining force, mental incapacity and physical incapacity.

“Sex without consent wasn’t a specific category of rape until this bill came along,” he said. “The end goal, in my mind, on the second bill was still the idea of defining consent. And so, I think we did it better.”

Heeren-Graber said that the bill, which cleared the House, was focused on the survivor who freezes during their attack, similar to Penny.

“Many times and from my experience, as well as working in this field for 30 plus years, victims will freeze, fight or flee,” she said. “Of course, and in many times, victims are freezing during that sexual assault, and they're just trying to survive it.”

But the day before the bill would’ve gone in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee, the South Dakota State’s Attorneys Association, which had previously been neutral, pulled its support. It wasn’t until later that Reed learned the association was worried that it would create room for the defendant to face a lesser penalty than rape without consent.

“They had some concerns there'd be some unintended consequences that the cases could get charged at a lesser degree than they had planned on,” he explained.

Again, South Dakota's attempt to define where consent fits into the question of sexual assault was frozen in time.

Where do we go from here?

Reed and Heeren-Graber are confident that in the next legislative session a consent bill will be passed.

However, as the year-anniversary of her assault comes up, Penny still lives in fear. She now has a permanent protection order against ''The Boy," according to court records obtained by the Argus Leader. But there are still times she thinks she sees him on the street and she has to do a double-take.

She panicked in February when she thought he was being released from jail on petty theft charges.

“I was crying. I was upset. I was shaking,” she said. “Just the fact that knowing that he could be around the corner brought me back to terror and fear and not knowing if I was going to run into him.”

To take care of herself, Penny goes to therapy and continues to get support from resources in the community dedicated to helping survivors of sexual violence, like the Compass Center.

She even adopted a kitten who likes to nibble on her.

Penny plans to continue speaking out and fighting back, not just for her own case but for other women and men, who question if what they experienced—whether it was last night, last week or last year — was assault.

“Something has to be done. This was physical and sexual assault. It still happened and I'm not done talking about it,” she said. “It's not about me anymore, but somebody’s got to know I'm not done. I'm not gonna shut up, and that helps my recovery.”

If you or someone you know has been sexually assaulted, please reach out to either the Compass Center (605)339-0116, the Children's Inn (605)338-4880 or the Sioux Falls Police Department (605)367-7212. Sexual assault exams are available at hospitals in Sioux Falls as well as The Link downtown.

Follow Annie Todd on Twitter @AnnieTodd96. Reach out to her with tips, questions and other community news at atodd@argusleader.com or give her a call at 605-215-3757.

This article originally appeared on Sioux Falls Argus Leader: No consent law in SD leaves survivors of sexual assault in legal limbo