Sharing Ortralla Mosley’s story turned teacher’s grief toward helping others

Editor’s note: This article describes abusive dating relationships and the violent murder of a high school student. Call the National Teen Dating Abuse Helpline at 866-331-9474, text “LOVEIS” to 22522 or visit loveisrespect.org for immediate, confidential assistance.

Vanessa Conner was in her first year of teaching at Reagan High School when a panicked student dragged her by the hand to the bloodied 15-year-old Ortralla Mosley, slumped at the bottom of the stairs.

It was 2003. Conner's first thought was Columbine.

But there was no gunfire amid the screams and the chaos as students fled the brick-walled corridors of the academic building. Only Ortralla — a bright student, drill team leader and generous friend — riddled with stab wounds.

The trauma of that March 28 attack, exactly 20 years ago this week, left a lasting imprint on Conner, now 59. Just a few hours after chatting with Ortralla at lunch and seeing her in English class, Conner held her hand as the teen died.

Then the depth of the horror sank in, all of the missed opportunities to spot the abuse and save Ortralla’s life.

So Conner vowed to tell Ortralla’s story as many times as she could — in her English classes, at school assemblies, to other students who might be experiencing teen dating violence, as Ortralla had.

For Conner, all of those retellings meant reliving the shock and anguish of that day. It’s how she turned her grief toward a purpose. Maybe Ortralla’s story could save someone else.

“And I told her story again, and again, and again, to literally thousands of kids,” said Conner, who left teaching in 2015. “And not a single time — not once — did I tell her story and not have a child come forward and say, ‘I need help.’”

Trouble under the surface

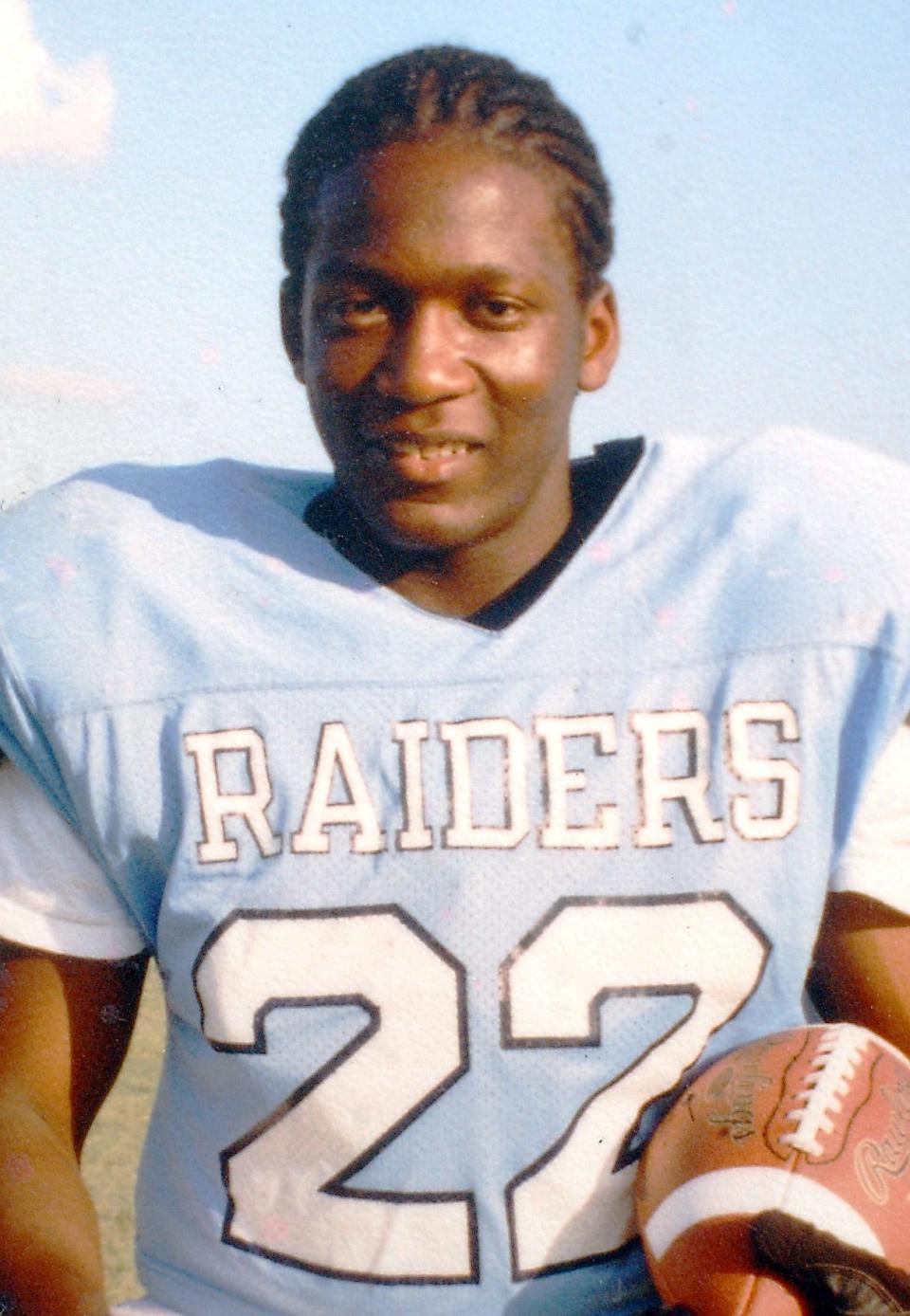

Ortralla and 16-year-old Marcus McTear were both in Conner’s sophomore English class in the fall of 2002. When they eventually started dating, Conner thought they were a great match.

McTear, a football player and member of the school choir, was “charming, and smart, and funny as heck,” Conner recalled. She still remembers how “scalawag” became his word after he studied the post-Civil War era in U.S. history class.

“Anything I would say that aggravated him, he'd say, ‘Miss Conner, you’re just being a scalawag,’” she recalled. “And everybody would start laughing.”

Ortralla, whom friends and family called Tralla, was big-hearted and unafraid to speak her mind. She pushed back when classmates at the largely Black and brown campus of Reagan, later renamed Northeast High School, made jokes about the hippie-style attire of a white teacher from Hawaii.

“I remember Tralla getting very upset in class and saying, ‘Y'all need to stop picking on that lady. She came here to teach you something,’” Conner recalled.

Outspoken and charismatic, McTear and Ortralla seemed like a dream couple, Conner said. But it was a stormy relationship. Some days they were clearly upset at each other. Other days they sat happily nestled, arm in arm.

“I think that most people who saw them thought, ‘She's such a strong young woman; she can handle him,’” Conner said. “But no one really knew what was happening.”

An alarming pattern of abuse

English class was right after lunch, so Ortralla and a friend often spent their lunch period in Conner’s room, too. At lunch on March 28, 2003, Conner could see the normally bubbly Ortralla was subdued.

Ortralla nodded to the homecoming picture of McTear and her on Conner’s bulletin board.

“Take the picture down,” Ortralla said.

“Did you and Marcus break up?” Conner asked.

“Yes, ma’am,” Ortralla said.

But Conner had seen them argue before.

“I’m not going to take it down yet, because I don’t believe it,” Conner told her. “I suspect you’ll get back together.”

That’s when Ortralla’s friend said, “Nope, this time is different.”

Only later, after Ortralla’s death, would Conner learn how bad it was: That McTear was controlling about the clothes Ortralla wore. That he had pushed his way into her house a few weeks earlier and held a knife to his own throat. That he had smashed her cellphone into a wall on March 27. That he had angrily followed Ortralla and her friend into the girls’ restroom on the morning of March 28.

At lunch that day, Conner learned only that McTear had called Ortralla names and threatened her. Conner was worried. But Ortralla told her everything was under control. She had already talked to an assistant principal.

All of the information that later came out about the case — through investigations, interviews and lawsuits — makes it clear that many things went wrong. Surveys now show that 1 in 11 teenage girls experience physical violence in a dating relationship. Two-thirds of teens who are dating report experiencing some form of abuse, whether it's physical, verbal or emotional.

But school administrators in 2003 weren’t versed in the concept of teen dating violence. They didn’t recognize the warning signs. They didn’t have procedures to defuse these volatile situations.

More broadly, administrators didn't seem to be responsive to students' problems. According to a report by the Reagan High School Safety Review Team, set up after Ortralla's death, fewer than half of the students at Reagan felt they could get help from campus administrators if they had safety concerns. Students in that survey said that "administrators ignore students, do not take them seriously, are too slow, or only attend to concerns that are of major consequence."

Worst of all, administrators at Reagan failed to address a pattern of abuse with McTear, who had been suspended for three days the previous school year after hitting a girlfriend in the head during theater class. A prosecutor later said McTear had at least six reports of a disturbance at Austin schools stretching back five years.

But the assistant principal that day told Ortralla to just stay away from him.

Read more

Ortralla Mosley’s mother sought help for her daughter’s killer. She’s done trying.

Time, distance and prison walls haven’t stopped Ortralla Mosley’s killer from reaching out

Losing Ortralla

McTear brought two 11-inch kitchen knives to school. He met up with Ortralla in an upstairs hallway near the end of the school day. When she refused to take him back, he stabbed her six times in the back, neck and head.

Ortralla managed to stagger down the stairs before collapsing.

Conner remembers the pandemonium as students poured into the hallway and saw their dying classmate at the bottom of a blood-streaked stairwell. Conner went from one student to the next: “Are you hurt? Are you stabbed? Are you shot? No? Get out of the building.”

Jackie Sanner, the school nurse who had once been an Army nurse, rushed to Ortralla's side. Conner could see it was bad. At first, Ortralla’s eyelids fluttered when Conner said her name. But her breathing was weak and raspy. Her life was draining away.

“I took her hand, and there were all those defensive wounds I could see on her arm,” Conner told me recently. “And I just held her hand in both of my hands, and I just said, ‘Baby, you got to stay with me.’”

Then Ortralla took one last breath and emptied her lungs. Sanner turned to Conner and said, “I think we’ve lost her.”

A battery of paramedics arrived, but Conner wouldn’t let go of Ortralla’s hand.

“I remember saying, no, I'm the only person here who knows her name, who knows who she is,” Conner said, her eyes welling with tears. “I know her. She's mine. She's one of mine.

“And as they pulled me back I heard this scream, and it was like a wounded animal,” Conner continued. “It was just this horrendous, horrible, agonizing scream, and it reverberated through that big concrete courtyard. And I looked up the stairs, and there was Marcus.”

He had the other knife. In one desperate jab, he cut into his own neck.

Others helped by the story

McTear survived, and police took him into custody. Two months later in juvenile court, the 16-year-old admitted guilt in Ortralla’s death and was sentenced to 40 years in prison. Now at the halfway mark of his sentence, McTear is being considered for parole.

For many years, this attack was a defining line for Conner. There was life before Ortralla’s death and life after it. Conner joined Ortralla’s mother, Carolyn White-Mosley, and other advocates to push for greater awareness and for policies to address teen dating violence.

In 2007, the Texas Legislature passed a bill by then-state Rep. Dawnna Dukes, a Reagan alum, that required school districts to develop dating violence policies. That included training for teachers and administrators, as well as plans for safely separating students and providing counseling.

In 2010, recognizing the tragedy of Ortralla’s case and too many others like it, Congress declared February to be National Teen Dating Violence Awareness and Prevention Month.

By then, Conner was at Stony Point High School in Round Rock, but she continued to tell Ortralla’s story to her classes and anyone else she thought she could help.

Sometimes students would see themselves in Ortralla.

Sometimes students would see themselves in McTear.

Either way, now they saw the danger. And now the schools had some tools to help.

Growing out of the dark

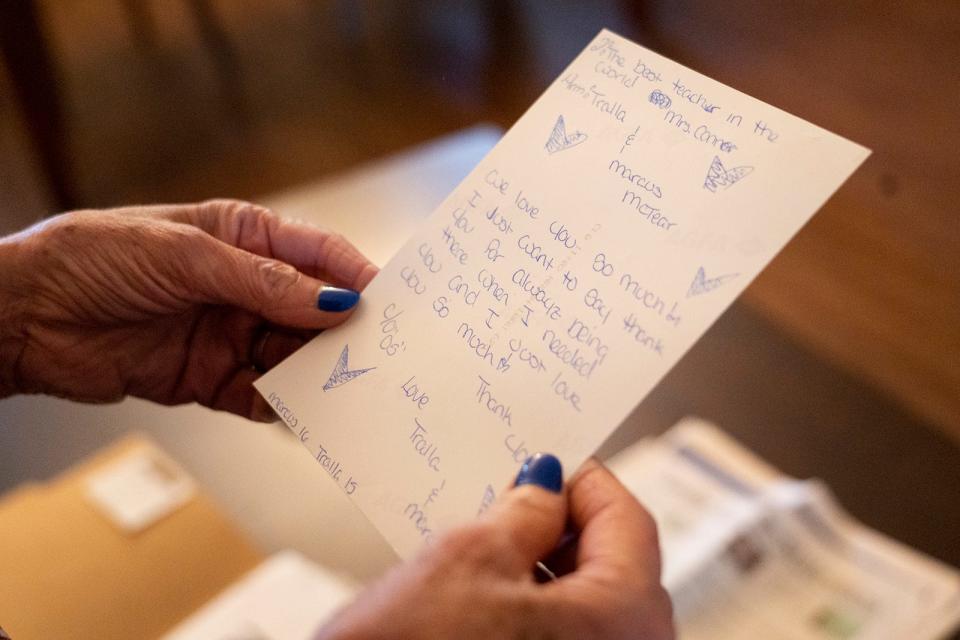

Conner still has a file of newspaper clippings and other remembrances of this case.

Ortralla’s sheet from the gradebook.

The program from her memorial service.

The work order moving Conner to a downstairs classroom, so she wouldn’t have to climb up that staircase every day.

She even kept some of Ortralla’s classwork, including an assignment on personification.

“I am like the sun. I brighten your day,” Ortralla wrote. “I am like the earth. I revolve around you.”

Conner and her sophomore English class worked through their grief together, at first with poems and essays. Then they started working in the spring of 2003 on a memorial for Ortralla.

In the center of the two-story academic building is an open-air courtyard, a square of sunlight and grass about 10 yards from the base of the steps where Ortralla died. Dietz Memorial donated a pink granite marker — Ortralla loved pink — with her name and the inscription, “We will never forget you, our angel.”

Another company donated the specific tree Ortralla’s classmates wanted, an Asian pear tree. It blooms in pink, always in late March.

The sapling was maybe 10 feet tall when students planted it in 2003. Now its branches soar above the second-story roofline.

“I’m astonished,” said Conner, sizing up the tree earlier this month, in her first visit to the campus in 17 years. “It’s so big.”

She grew emotional, flooded by the memories of the day that made a monument necessary. But all that stood there now was the tree that kept growing and blooming after Ortralla no longer could.

Conner kissed her hand, then pressed it into the ashen bark of the trunk. “Goodbye, girl,” she said with pride. “You did good.”

The limbs, spindly and bearing the promise of buds, stretched toward the sun.

Dating abuse is a pattern of coercive, intimidating, or manipulative behaviors used to exert power and control over a partner. Such behaviors by an abusive person may include:

• Checking your phone, email or social media accounts without your permission

• Putting you down frequently, especially in front of others

• Isolating you from friends or family — physically, financially or emotionally

• Extreme jealousy or insecurity

• Explosive outbursts, temper or mood swings

• Any form of physical harm

• Possessiveness or controlling behavior

• Pressuring or forcing you to have sex

For support, call the National Teen Dating Abuse Helpline at 1-866-331-9474, text “LOVEIS” to 22522 or visit loveisrespect.org.

SAFE offers Expect Respect support groups in some middle and high schools to help young people who have been exposed to violence in the community, at home or in peer relationships. All services are free, confidential and provided at school during the day. To learn more, or to talk to someone about teen dating violence, email expectrespect@safeaustin.org or contact the 24-hour SAFEline at 512-267-7233; text 737-888-7233; or chat at safeaustin.org/chat.

Source: Love is Respect, a project of the National Domestic Violence Hotline

Grumet is the Statesman’s Metro columnist. Her column, ATX in Context, contains her opinions. Share yours via email at bgrumet@statesman.com or via Twitter at @bgrumet. Find her previous work at statesman.com/news/columns.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Story of Ortralla Mosley's murder raised awareness of dating violence