Sharks are here to stay on the South Shore. What it means for Massachusetts beachgoers

Far more sharks are in the waters off the South Shore than previously thought.

As a bonus, it also looks like they hang around longer each year.

The good news? They’re just not that into us.

“Sharks aren’t that interested in people,” shark expert John Chisholm said. “We have sharks any time we go in the water.”

The adjunct scientist for the fisheries, science and emerging technologies program at the New England Aquarium’s Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life has been studying sharks for nearly 50 years.

“We’re tagging more (of the sharks), so we’re recording more,” he said. “But they are here and have been long before the Pilgrims, and their numbers are only increasing.”

Chisholm spent 30 years working for the state Division of Marine Fisheries as a conservation assistant, fisheries supervisor and aquatic biologist with a wide range of responsibilities that included work on the Massachusetts shark research program with Gregory Skomal.

Chisholm has witnessed the increase in the overall shark population through both firsthand observation and tracking techniques that benefit from technology advances.

How many great whites sharks have been detected near Massachusetts?

Last year, 134 previously tagged sharks were detected by 69 receivers concentrated along the Outer Cape, where the sharks are most populous, into Cape Cod Bay and then along the beaches of the South Shore and as far north as Cape Ann.

A sharp increase in the number of previously tagged sharks was detected by the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy in the preceding years: 130 in 2021, 116 in 2020, 99 in 2019 and 63 in 2018.

Since 2014, the researchers have recorded more than 600 individual visits in the coverage region.

The Atlantic White Shark Conservancy, a Cape-based organization, works alongside the New England Aquarium, the state’s Division of Marine Fisheries and other organizations in both tracking the sharks and educating the public about their presence.

Summer 2023: First white shark of the season sighted off Provincetown, public reminded to be aware

Why are the sharks coming close to Massachusetts shores?

Attracting the sharks is a dense population of seals, whose numbers continue to grow in the northwest Atlantic because of federal protections put in place in the 1970s. The gray seals were protected after intense hunting over the previous couple of centuries had nearly wiped them out.

The number of white sharks dropped in the 1980s and 1990s with the expansion of commercial and recreational fishing. Since aquatic mammals were listed in 1997 as a species that people could not hunt, capture or kill in the northwest Atlantic, their numbers are rebounding.

How to avoid being attacked by a shark

Chisholm said it's important for area beachgoers to be “shark smart,” which starts with one simple rule.

“Don’t swim with the bait,” he said.

That goes beyond avoiding being in the water where seals are nearby. He said birds are an indicator of schools of fish, which sharks are just as happy to snack on. So people should avoid those areas.

“The ocean is a wilderness area,” Chisholm said. “The more sharks we tag, the more we see detections all along the South Shore, and people should be aware of that and pay attention to their surroundings.”

Acoustic detection buoys will help locate sharks in Cape Cod Bay and Massachusetts Bay

Despite the focus on the Cape, the seal population continues to grow on the South Shore, with areas including Brant Rock in Marshfield showing notable increases.

Chisholm said it’s not just human sightings that provide evidence of the sharks’ presence.

“We have already seen several seals on the South Shore showing up with shark bites,” he said. “That we don’t see (the sharks) doesn’t mean there isn’t activity.”

Towns including Scituate, Marshfield, Duxbury and Plymouth have joined in the effort to warn people about the sharks’ presence − even if the risk of interaction is low − and aid in research efforts to gauge the number of tagged sharks present in the hopes of establishing their behavioral patterns and migratory schedules.

In just the past few weeks, the harbormasters in many of those towns have posted pictures of their staff deploying acoustic detection buoys in the water that capture information on the presence of tagged sharks passing within range.

The data will be retrieved when the buoys are pulled from the water in the winter.

Atlantic White Shark Conservancy's White Shark Logbook: Here's what information it collects

All the data is now publicly shared on an interactive web application accessible via the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy's White Shark Logbook website, which scientists have been building over the last couple of years.

Camera tags used to collect data and video are increasingly favored over standard acoustic tags. They can either be tethered via a dart or clamped onto a shark's dorsal fin. They record data 20 times a second and last about 11 hours.

Summer safety tips: 'Everyone going into the ocean should exercise caution.' Reduce the risk of a shark attack

Scientists are also using solar-powered, real-time receivers, which can send alerts to lifeguards and other public safety officials within seconds of a tagged white shark coming in range.

At $16,000 per device, the number of deployments is limited.

Although several have been used along the Cape using grant money and other sources, Marshfield is the first town to invest in two of its own real-time receivers.

Drones, which made their debut last summer, are also helping researchers.

What the Sharktivity app shows

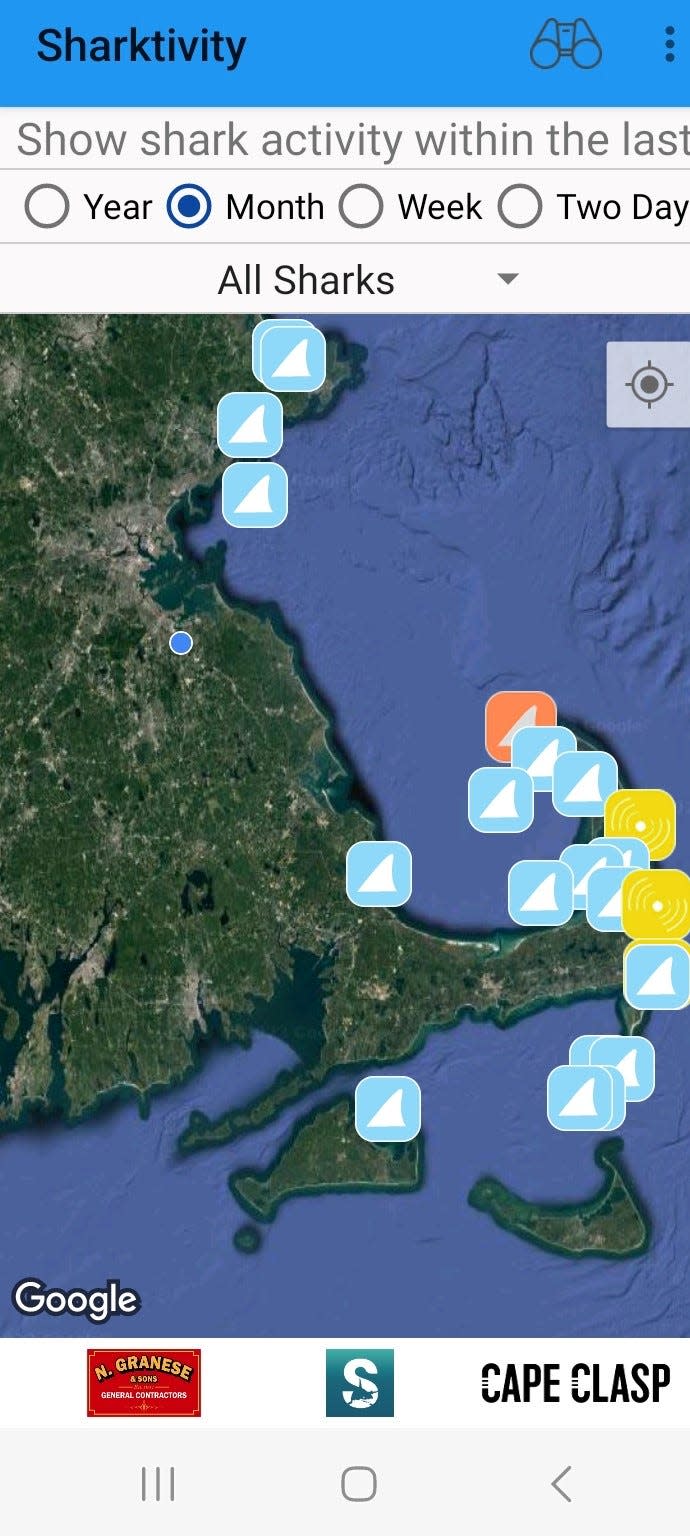

Absent more receivers, efforts have been undertaken to provide real-time alerts from existing receivers to the wider public by tying in its Sharktivity app, which provides information and push notifications to users on white shark sightings, detections and movements.

More: 'Smart phones' for sharks. Cape scientists use the latest tech to keep track of predators

The app is a joint effort of the conservancy and the aquarium.

“In the late '70s, we’d hear a rumor (of a sighting), and it would take days to months to years to try to confirm,” he said. “Everybody has a camera and computer on their hip now, so the nice thing now is (the app) allows the public to contribute to what we know."

Chisholm is responsible for vetting the reports that come in to the app.

"There's a lot of misidentifications,” he said. “Still, it is a help every year as it gets more word of mouth and awareness."

Is climate change bringing sharks to Massachusetts?

Chisholm said tying climate change to sightings of sharks all the way north to Maine is a misconception.

Those sightings, he said, are not new. The cold-blooded great whites can generate more body heat than they are credited for.

“These sharks like cool water, and they historically have always been here,” he said.

Inside our oceans: Massachusetts coastal waters home to jellyfish, sharks, and other biting, stinging creatures

Great white sharks can raise their temperatures through metabolically heated blood, which works by using the heat generated from active swimming muscles and the shark's metabolism to warm its body's core and major organs.

“It helps them retain the heat, tolerate colder waters, digest food faster and see better,” Chisholm said. “We have sharks all the way into the winter. A majority go south, but they can tolerate a pretty wide range of water temperatures.”

Human-shark interactions are rare on South Shore and Cape

In a review of 10 years of reports from the online International Shark Attack File, Massachusetts has only had a handful of human-shark incidents. A 2018 attack on the Cape marked the only fatality since 1936.

While most incidents are reported to occur on the Cape, there was one in Gloucester and one off Manomet Point in Plymouth. None were reported along the South Shore.

In fact, close-to-shore shark sightings are extremely rare around here, and there’s a reason for that, Chisholm said: The nearshore water is relatively shallow in much of the area.

That prevents sharks from coming close to beachgoers, or at least those who remain about hip-deep in the water.

Why do people have a fear and loathing of sharks?

“Shark attacks, even if just one, instill fear in people,” Chisholm said. The fatal attack in 2018 was one such case.

More: Man dies after shark bite on Cape Cod

Arthur Medici, 26, of Revere, was bitten by a shark while boogie boarding in a wetsuit and flippers at Newcomb Hollow Beach in Wellfleet in September of that year. He later died from his injuries.

“It only takes one to make a real impact on local communities,” Chisholm said.

Besides great whites, what types of sharks are in Massachusetts?

He noted that while great whites grab all the attention, Massachusetts is home to numerous species, including mako, basking, blue and sand sharks.

He said Plymouth, Kingston, Duxbury and Quincy bays serve as nurseries for juvenile sand tiger sharks.

He credits local coastal towns for doing a good job posting signs warning of things like sharks and undertows.

“There is a much bigger effort with all local communities to make sure no one who comes to the beach is unaware this is where they live and hunt,” he said. “That being said, people can still go to the beach and enjoy themselves.”

This article originally appeared on The Patriot Ledger: Massachusetts and Cape Cod bays are home for many sharks. What to know