Shasta County residents speak about recovery, stigma amid rise of fentanyl overdose deaths

Shasta County had a record number of fentanyl overdose deaths in 2021, mirroring a disturbing national trend that has seen a fast and alarming rise in fatalities fueled by the opioid.

The powerful drug killed 40 people last year, almost six times as many people who died from a fentanyl overdose in 2020, according to a Shasta County Health and Human Services (HHSA) report released in June.

People ages 25 to 34 were most affected, but people in all age groups and from different income brackets died.

Those on the front line of the county's drug war seek to stem the problem with drugs that stop overdoses and therapies that combine counseling and new medications, but the problem is overwhelming.

“If this pace continues, Shasta County could see ten or more times the number of deaths this year from fentanyl compared to 2020,” HHSA Community Education Specialist Amy Koslosky said.

Alcohol-related deaths are steadily on the rise, too, according to the county. In 2021, 77 people died from alcohol poisonings and illnesses, compared to 42 in 2012. The majority, 84%, were ages 45 to 74.

“Every shift, I see the consequences of substance abuse in one form or another: alcohol, methamphetamine or tobacco,” said Dr. Charles Mansell, an emergency room doctor at Mercy Medical Center in Redding.

In the news:

Overdose deaths among Black and Indigenous people surged in 2020

Study: Are you under 40? Even small amounts of alcohol may not be good for you

Doctors and therapists also spoke of efforts to make naloxone — a medicine that rapidly reverses an opioid overdose — more widely available to save lives.

Meanwhile, stay-at-home orders and physical distancing guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted treatment programs and led some to experience stress and anxiety.

A lot of people relapsed during the shutdown, said Marjeanne Stone, executive director at Empire Recovery Center in Redding. Some clients never returned to therapy programs, many of which had to cut services or — in the case of Empire — shift to teletherapy.

Mansell said he's seeing "a lot more" alcohol-related problems in the ER since the pandemic started, such as traumatic injuries, intoxicated injuries, liver disease and liver failure.

Overall, opioid poisonings increased since 2016, according to county data.

From 2016 to 2021, the average was 22.7 deaths per year.

From just 2019 to 2021 the average was 29 deaths per year.

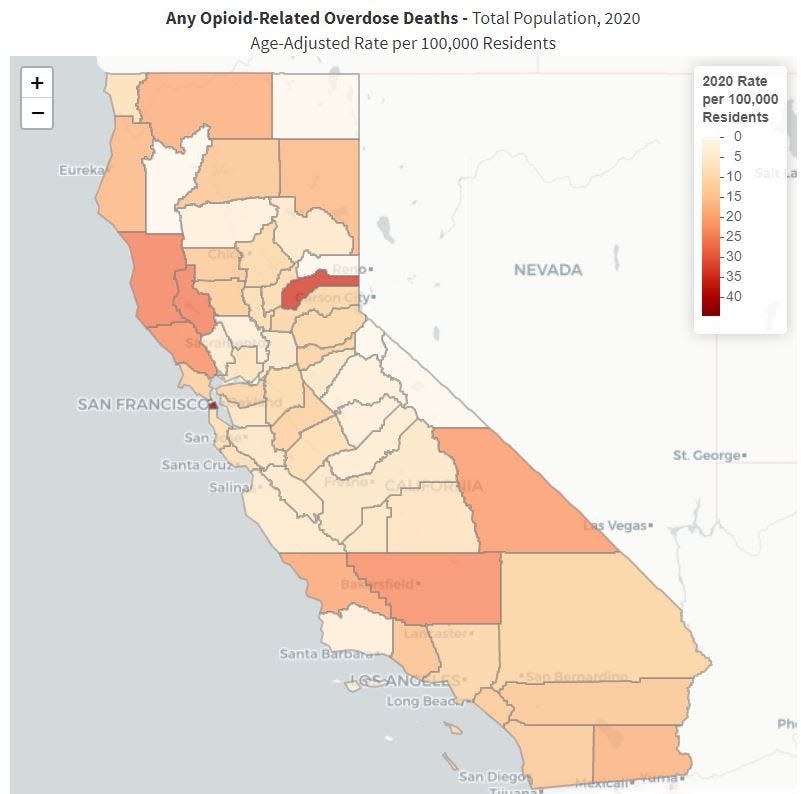

Among California's 58 counties, Shasta County ranked 14th in opioid-related deaths and 19th in ER visits in 2020, according to the California Department of Public Health.

Fentanyl deaths rise nationwide

What's pushing opioid fatalities is rising fentanyl use, Koslosky said, despite newer medications like Narcan that can reverse opioid overdoses. Originally created to battle severe pain in cancer and surgery patients, fentanyl is an opioid “similar to morphine but up to 100 times more potent."

Fentanyl and other drug-related deaths are a growing problem nationwide:

In 2020, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported a record of more than 93,000 drug overdose deaths.

In California, drug overdoses will likely increase 17% in 2022 over 2021, according to U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention projections.

Fentanyl is less expensive than other drugs and more poisonous, according to HHSA's Injury and Substance Abuse Prevention supervisor Cory Brown and Mental Health and Alcohol and Drug Programs manager Katie Cassidy.

Emergency room visits for methadone and heroin poisonings dropped slightly in 2020, but fentanyl visits are more common.

"It’s just about replaced heroin on the street.” Redding police Sgt. Gary Meadows said.

He also noted that fentanyl-related arrests, too, are on the rise.

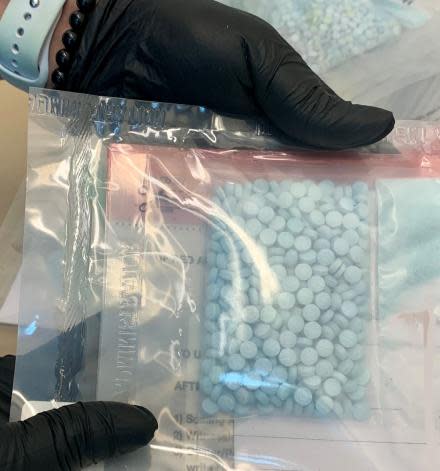

Just touching fentanyl can cause an overdose, Meadows said.

Dealers may lace marijuana, methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin or other drugs with fentanyl, said Lt. Chris Edwards at the Shasta County Sheriff’s Office. Those who buy the drugs may not know they're using fentanyl.

Mixing fentanyl into other drugs can lower the cost, but dealers can easily use too much, according to the county. As little as 2 milligrams of fentanyl — the weight of a small mosquito — can kill.

That puts doctors in the odd position of having to educate those who buy drugs, Mansell said. “It’s hard to tell someone how to use drugs, but we have to do so,” like have a sober friend present to call for help if you get in trouble.

Ultimately, the only way to avoid risk is to stop using, Mansell said.

How county addresses growing problem

Shasta County doctors and police are taking advantage of new drugs that stop some overdoses.

Police carry and are trained to use Narcan — a medicine that quickly reverse an opioid overdose, Meadows said. “That’s one of the reasons people are (surviving)."

Other drugs help reduce withdrawal symptoms and alleviate cravings, said Mansell, who remembers the first patient — a regular in the ER —for whom he prescribed suboxone. The change was almost immediate.

Doctors are also trying to stop problems before they happen. In 2022, patients prescribed opiates for pain also go home with Narcan — just in case, Mansell said.

Doctors also monitor patients on painkillers for signs of addiction more carefully now than they did in the past.

Looking for signs of addiction is key to stopping a problem before it spirals.

Read more: California advances bid to create legal drug injection sites as opioid crisis deepens

“The average person thinks it’s a matter of willpower. That’s what I once thought," said Jake, 31.

The Shasta County resident grew up in a religious family with no addiction disorders, he said. He hoped to join the military like his father, but at 10 and with epilepsy, he began having three or more grand mal seizures per week followed by searing headaches and muscle pain.

He started drinking at 11, he said. “It made me forget about the seizures."

But his illness got worse. He was on eight prescribed medications, "about 100 pills a day,” he said.

At 20, alcohol stopped helping. He was having nine large and 20 small seizures daily.

A friend who saw him suffering offered him methamphetamine.

“In that kind of pain, you forget everything you’ve been told about the dangers of what meth can do,” Jake said.

It took away the pain immediately — at first. A year later, he was unable to cope without it.

By 24, the 6-foot man weighed 130 pounds, was homeless and used over an ounce of meth a day. He’d wake up in the emergency room five times a week, he said.

“All you can think about is what you’ve been told about drug addicts: They’re bad people," Jake said. "Every time you mess up, you beat yourself up psychologically.”

Cravings were like being underwater too long and your lungs scream in pain for air, Jake said. Worse is the "psychological torture. You feel like you’re going to go insane.”

Withdrawal symptoms begin as early as 12 hours after the last dose and peak in 48 hours, according to the National Library of Medicine. Immediate symptoms like intense physical pain may end after a week, but acute long-term symptoms like depression and cravings can last months or years.

At 25, Jake entered a 12-step and a sober living program. After three relapses, he managed to quit. He has been sober for six years.

“Despite the horror and the hell of addiction, there is hope,” he said, especially if problems are caught early.

MAT program sparks hope for recovery

In addition to watching prescription patients for signs of addiction, doctors are using new medications to create recovery programs for people already addicted.

Stopping a person dying from an overdose is “one of the most rewarding things I can do," Mansell said, "but then the question is: How can we prevent this from happening again?"

Mercy launched its medication-assisted therapy (MAT) program in November 2018 at its Mount Shasta facility, and in October 2019 in Redding, spokeswoman Allison Hendrickson said. Doctors prescribed suboxone, a prescription medication that helps reduce cravings for prescribed and illegal opioids, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

A MAT program helped Sam of Shasta County get off drugs.

When he was 16 years old, he broke his leg wrestling, he said. His doctor prescribed Norco (hydrocodone) for the pain.

“The first time I took it, I felt euphoric,” he recalled. “It got rid of all my anxiety. It made me feel more social. I just felt good.”

When the prescriptions stopped eight months later, he went into withdrawal. He bought Norco illegally to stop the pain.

Withdrawal "is the worst feeling ever," he said: Vomiting, nausea, diarrhea, body aches, chills and “you can’t stop moving your legs.”

Worse were the psychological symptoms, he said. “It’s overwhelming: The worry, the existential dread. That’s what keeps people from quitting.”

After several unsuccessful attempts, medication-assisted therapy helped him do just that, Sam said. At 25, he has been sober for four years.

Clear trajectory: Healers cope, too

Even with new therapies, the addiction problem can feel almost as insurmountable for healers as it does for those who suffer with addiction.

Doctors need to feel hope for patients, Mansell said. "You have to protect yourself so you don’t internalize too much of the trauma.”

Mansell credits family for "revitalizing" him and other ER staff. His self-care regime includes a Thursday morning ritual: He and his 3-year-old son go outside to watch a garbage truck roll through their Northern California neighborhood, picking up trash bins. “My son loves ambulances and garbage trucks,” Mansell said.

Watching noisy ambulances is the limit of his son’s understanding of the pressures he faces at work. Mansell does four or more eight- to 10-hour shifts per week at Mercy and St. Elizabeth Community Hospital in Red Bluff.

He treats patients with overdoses during every shift, Mansell said, some who return to the ER "multiple times a week or month" for alcohol or opioid use disorders and other drug-related problems.

"With drug use, there’s a clear trajectory," he said. "Your life will go from daily use to ending up in the ER, or worse."

Mary of Shasta County was one of the lucky people who survived an overdose in the ER.

Eleven years ago, she woke up in the back of an ambulance after taking heroin. While in the hospital she went into "full blown withdrawal," she said. A tsunami of anxiety washed over her. "You feel like your body is breaking.”

It was a year before she was able to stop taking opioids, but her overdose was a linchpin moment, she said: "At some point you realize, ‘I might not have woken up.’”

Now 34, Mary has been sober for 10 years.

Surviving an overdose in the ER can be the event that puts a person on the road to recovery, Mansell said. "It’s going to be one of the worst days of their life."

The three people interviewed who overcame addiction expressed hope others will learn from their stories. Few people identify their own prejudices — that awareness usually comes from those misjudged — but once they do, they can decide to discard those attitudes.

The Record Searchlight isn't providing their full names to protect their privacy.

Jessica Skropanic is a features reporter for the Record Searchlight/USA Today Network. She covers science, arts, social issues and entertainment stories. Follow her on Twitter @RS_JSkropanic and on Facebook. Join Jessica in the Get Out! Nor Cal recreation Facebook group. To support and sustain this work, please subscribe today. Thank you.

This article originally appeared on Redding Record Searchlight: Shasta County drug, alcohol deaths rise as new treatments emerge