‘Shattered a community’: Family speaks against parole for killer of Prairie Village girl

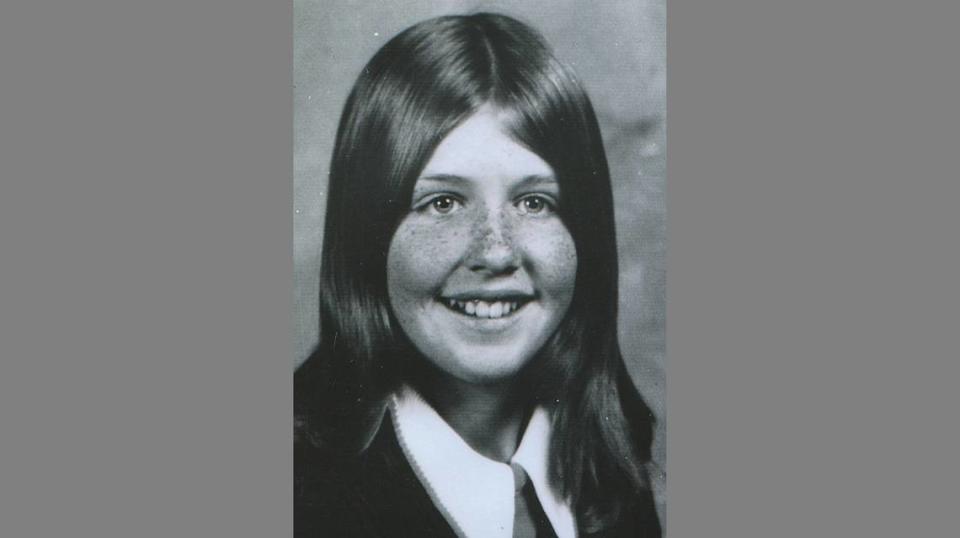

Alex Wilson fought back tears as he searched for words to describe how much pain his family has endured since his sister, Lizabeth Wilson, was killed nearly 50 years ago.

“On July 7, 1974, John Henry Horton kidnapped, raped and murdered a 13-year-year old girl; he then dumped her body in a field,” Wilson said. “I would like to think that that statement should be enough for him to be behind bars forever.”

The case, one of Johnson County’s most notorious, remained cold for decades. It eventually was reopened, and Horton was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison for the Prairie Village teen’s murder. Prosecutors had argued that he drugged her with chloroform to subdue her before assaulting and killing her.

Now Horton is eligible for parole again this year.

The Kansas Prisoner Review Board held a public comment session Wednesday via Zoom, the first of two such sessions to help determine if Horton will remain behind bars. The video sessions precede a parole hearing for Horton, who is now 76 years old, that will be held next month. If granted parole, the earliest he could be released is November.

Members of Lizabeth’s family and the former detective who helped solve the case urged the board to keep him locked up.

Alex Wilson said there were no words to adequately describe how much pain his family has been put through. He recalled the sorrow of the six months she was missing, the anguishing discovery of her remains and the decades of pain he watched his parents in particular experience after her murder. He remembered often finding his mother alone and crying.

He recognized there is no such thing as “perfect justice” in the world. It’s a Utopian dream, he said.

“The goal here is to get as close as we can to that standard . . .,” said Wilson, who spoke on behalf of Lizabeth’s two other brothers as well. “We’ll never achieve justice. No, that’s not possible.”

Headed home from pool

Lizabeth Wilson was last seen cutting through the parking lot of Shawnee Mission East High School on her way home from the pool on July 7, 1974.

Six months later, her skeletal remains were found at a Lenexa construction site.

The day after she disappeared, Prairie Village police questioned Horton, who denied knowing what happened to her.

Investigators found a container of ether and several bottles of chloroform in his trunk. He claimed he had stolen the items from the school’s science lab, planning to get high on the chemicals.

Decades later, at one of his trials, a retired FBI chemist testified that hair on items in Horton’s car were “very, very similar” to hairs taken from Lizabeth’s hair brush. The chemist also said hair found in a room of the high school were also similar on a microscopic level to hair from the brush.

The chemist, on cross-examination, said those tests were performed before the advent of DNA testing and by the time DNA tests were available, the hairs had been destroyed.

Police also interviewed cheerleaders and tennis players who had been outside the school on the day Lizabeth disappeared. They said Horton had approached them and tried to get them to go inside the building, but they said they refused.

Although he was a suspect from the start of the investigation, nearly three decades would pass before charges were filed in Lizabeth’s killing.

Case case reopened

In 2001, Kyle Shipps, a now-retired detective with the Prairie Village Police Department, asked for permission to look into the case. He had not been with the department during the initial investigation, but was intrigued by the cold case.

Shipps teamed up with the Kansas Bureau of Investigation, and they tracked down old leads and came up with a new one that cracked the case.

They found a woman, who in 1974, was 14. She lived across the street from Horton. One night, she said she went with Horton and his niece to a nearby golf course. There, Horton talked her into sniffing a chloroform-soaked rag to get high, she said.

She passed out and when she came to, her pants were partially down and Horton was fondling her, she said.

Prosecutors charged Horton with first-degree murder in 2003. Prosecutors said at trial that Horton lured Lizabeth into Shawnee Mission East, where he worked as a janitor, to molest her and then subdued her with chloroform before assaulting and killing her.

It took two trials and lengthy court appeals to convict Horton of first-degree murder. He was sentenced to life in prison. The Kansas Supreme upheld his conviction in 2014.

Under Kansas law at the time of killing, life meant serving 15 years before being eligible for parole. Because he was initially arrested in 2003, he became eligible for parole in 2018. That year, the prisoner review board denied parole and ordered him to wait until 2023 for his next chance to be released from prison.

Threat to community

During the hearing, family members spoke about Lizabeth and the impact her killing had on them.

“She was probably the sweetest little girl you ever want to meet,” said her uncle, Joe Hanrahan. “She laughed. She was kind. She was innocent. She was very, very sharp.”

She was going to be an amazing person, Hanrahan said. Because of Horton, she didn’t get to go to high school or college, or get married or become a mother. She wasn’t there when her mother fell ill.

Every day following her disappearance was hard for her parents, who are both deceased, Hanrahan said.

“His punishment should always be that the last breath he takes in life is there in prison,” he said.

To say Horton shattered the lives of Lizabeth’s family is an understatement, said Shipps, the retired Prairie Village detective and lead investigator in the case when it was reopened.

“It goes far beyond that,” he said. “He shattered a community.”

The killing became national news and caused community members to question their safety and security, he said.

“Before that, people never locked their doors,” Shipps said. “Before that, they trusted their kids to walk alone. That all went away after this.”

Horton has shown no remorse, and he never admitted his actions or offered atonement for them, Shipps said.

Agreeing with family members who contend Horton remains a threat to the community if released, Shipps said the investigation showed he tried to entice other young girls into the school that day and that he had experimented with chloroform on another victim a week before.

Horton also allegedly committed similar activities, including peeping and trying to entice young girls in another community he moved to after the investigation centered on him, Shipps said.

Shipps referred to a quote that he kept above his desk throughout the investigation and trials, which read, “To the living we owe respect. To the dead we owe the truth.”

“The truth is that she was brutally, senselessly murdered by the defendant and he has been imprisoned for his actions and he deserves to stay there,” he said.