She Came to Slay: Tubman biography looks beyond Underground Railroad

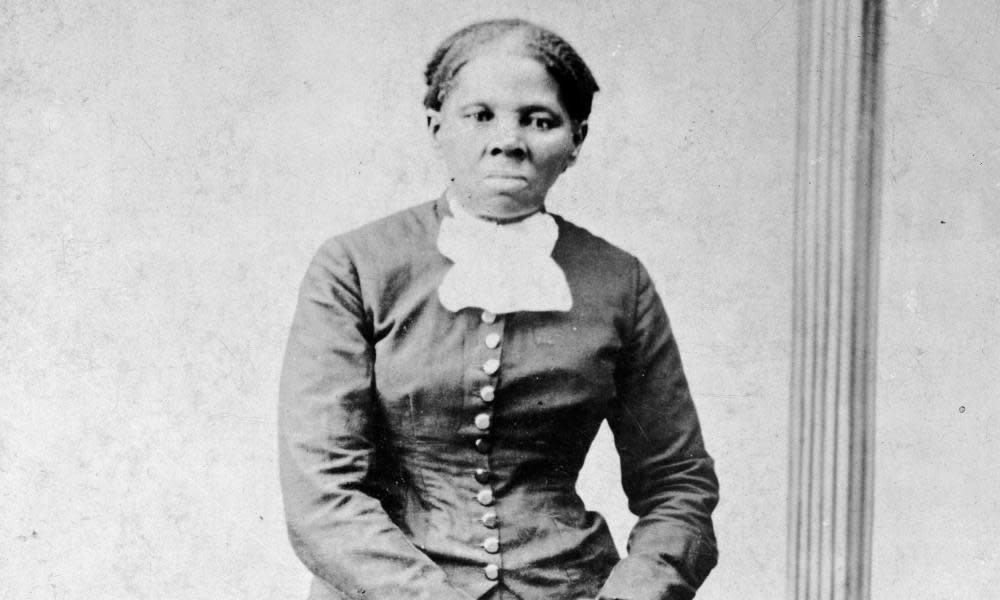

Harriet Tubman is one of the best-known women in US history, but most people know little of her life beyond what they learned in a history textbook.

Now, however, she is firmly in the spotlight. Her first biopic was released in US theaters on Friday and on Tuesday comes a new biography that considers her life beyond her famous work leading enslaved people to freedom on the Underground Railroad.

Related: Harriet review – Cynthia Erivo is sublime as legendary slave rebel

“What we think we know about Tubman really only consists of a decade of her life,” said Erica Armstrong Dunbar, author of the new biography She Came to Slay.

Among 200-year-old facts that will be new to many is that Tubman was the first woman in US history to plan and lead an armed expedition, liberating nearly 750 enslaved men and women in the process. She also fought for decades to gain compensation for her work as a spy, scout and nurse during the civil war and was an advocate for both women’s suffrage and proper care of the elderly.

“Tubman did not just become Tubman overnight,” said Dunbar, the Charles and Mary Beard professor of history at Rutgers University in New Jersey.

At the age of five, when she was an enslaved child named Araminta Ross, Tubman was separated from her family to work on a nearby Maryland farm. She was forced to do housekeeping, weaving and muskrat trapping in harsh and unrelenting conditions.

Sometime when she was 12 to 14 years old, an overseer threw a 2lb weight at a runaway but hit Araminta instead, breaking her skull and leaving her with what modern medicine would call epilepsy. For the rest of her life, she saw her bouts of unconsciousness and seizures as an ongoing conversation with God.

“Often,” Dunbar said, “Tubman is introduced at the moment of her escape in 1849, and to me that feels incomplete – it means we’re actually erasing 27 years of her life and then, of course, the people who came before her.

“I chose to begin She Came to Slay with the transatlantic voyage of her grandmother. I wanted to connect Tubman to her African ancestry; she was only two generations removed from that.”

As its title suggests, the biography is meant to be more accessible than traditional historical works. Its 136 pages include illustrations of key life events and infographics with titles such as It’s All About the Tubmans, which depicts key financial figures in her life, including the amount her father paid to free her mother: $20.

The new film, Harriet, also focuses on Tubman’s younger years, but ends during the civil war. Dunbar hopes it will whet appetites for people to learn more about Tubman’s work in and after the war, such as her role in fighting for women’s suffrage and supporting black people as they searched for work, healthcare and education in a world that still treated them as second-class citizens.

The film is the first biopic about Tubman, a fact not lost on most reviewers.

“Harriet Tubman finally has her biopic,” said Entertainment Weekly, while the Hollywood Reporter said the film was about “an important chapter in American history too long neglected by Hollywood”. When Harriet premiered at the Toronto international film festival in September, the festival director, Cameron Bailey, noted there were 30 films about George Armstrong Custer, a civil war commander. This was the first about Tubman.

It is no coincidence book and film are coming out at the end of 2019. There was a surge in interest in Tubman when Barack Obama, as president, said the $20 bill would be redesigned to feature her face by 2020.

In May, the Trump administration announced the change would be delayed until 2026, for technical reasons.

Shortly after that announcement, a conceptual design of the bill was leaked from the US Treasury. Its future seems uncertain, not least because Trump has said it would be “pure political correctness” to put Tubman on the $20 instead of Andrew Jackson.

“Well, Andrew Jackson had a great history, and I think it’s very rough when you take somebody off the bill,” Trump said in April 2016. “I think Harriet Tubman is fantastic, but I would love to leave Andrew Jackson or see if we can maybe come up with another denomination.”

Like the presidents on the $1 (George Washington) $2 (Thomas Jefferson) and $50 (Ulysses S Grant) bills, Jackson owned slaves. He also forcibly relocated 16,000 Native Americans on the Trail of Tears.

Related: 'I guess that's revealing': David Rubenstein on Trump and the weight of history

Others have questioned the wisdom of putting Tubman on the $20 for a different reason: because American capitalism was built on slavery and Tubman was once treated as property and exchanged for money.

“I hope it [the Tubman $20] drives a conversation about the value of black life, period, from slavery to the present,” Dunbar said. “I don’t think we can have her on the bill without us having that conversation.”

Dunbar said she was looking forward to opening her wallet to see Tubman instead of Jackson. A running theme in her book is the dollar value placed on Tubman and her family.

“It was important for readers to be able to connect the value of money,” she said, “and also to grapple with the fact that a bounty was placed on Tubman’s head – that Tubman was bought and sold for currency.”

She wanted, Dunbar said, to ask: “What does it mean for us to replace the image of a president with the image of an enslaved woman who would’ve been bought or sold for several $20 bills?”