'She was dying': Why thousands of NY nursing home complaints during COVID are unresolved

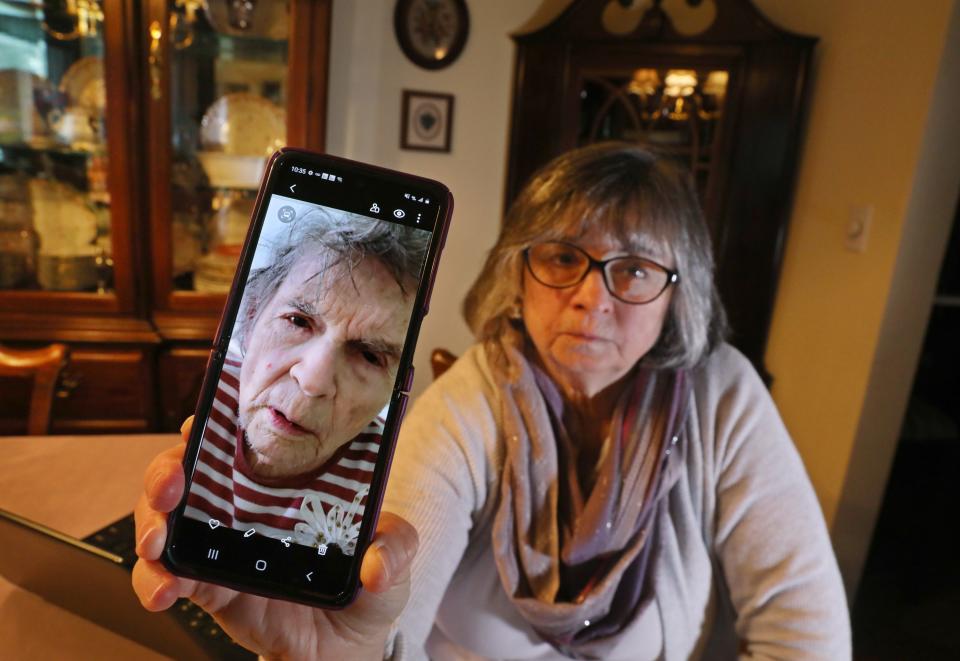

As the early weeks of the pandemic locked down nursing homes, Jeannie Wells could only watch from afar as her 91-year-old mother's health rapidly deteriorated.

Wells grew so alarmed that she filed a complaint with New York's Health Department, hoping officials could investigate what she wasn't allowed to see for herself. But the agency determined her concerns were unsubstantiated.

In the end, the truth only came to light, Wells said, when she gained access to her mother's room in a Rochester-area nursing home several months after the state’s nursing home visitation ban ended in February of last year.

We cover the stories from the New York State Capitol and across New York that matter most to you and your family. Please consider supporting our efforts with a subscription to the New York publication nearest you.

Even today, the memory of that first indoor visit is harrowing: the urine-soaked mattress where her mother had been sleeping. Brown crusty filth stuck on the bathroom wall.

Finally, in November 2021, Wells discovered her mother in the nursing home unresponsive and unattended.

“She was stripped of her dignity, suffering from dementia and dehydration in an unsafe environment,” Wells recalled. “Her door was closed, and she was dying.”

Two days later, her mother, Janet Deisenroth, died.

The official cause was ruled failure to thrive, a general catchall determination used for elderly deaths. But Wells believes malnutrition and neglect played a role — despite state health officials' earlier dismissal of her concerns.

Now, she's continuing her fight for accountability.

Newly reported nursing home complaint data revealed Wells’ experience is far from rare, according to a USA TODAY Network New York analysis of state records and interviews with a dozen people who filed complaints during the pandemic.

The months-long investigation uncovered how state health officials left thousands of complaint cases unresolved for more than a year, while deeming most other complaints "unsubstantiated," meaning they fell short of violation standards, state data obtained via public-records request show.

Put simply: The complaint system left thousands of people on their own to address health and safety concerns at nursing homes as COVID-19 ravaged the facilities, killing more than 15,000 residents.

Among the USA TODAY Network findings:

More than 35,600 nursing home complaints were filed in New York between Jan. 1, 2020 and Jan. 14, 2022.

Only about 4% of those complaints were substantiated as health and safety violations, while 47% were deemed unsubstantiated.

Another 16,865 of the complaints, or 49%, remained unresolved, including nearly 6,000 cases that were ongoing at least a year later.

The most frequent complaints included infection-control failures, family and resident notification problems, resident-to-resident abuse and physical environment concerns.

Those findings are echoed in stories shared with the USA TODAY Network New York, from people who recalled complaints about resident injuries, unsafe living conditions and daily examples of neglect seemingly languishing unresolved for months.

As Wells recounted her nursing home saga, she described the state Department of Health’s response to her complaints as stunningly inadequate.

“They said they went in and looked into it and had the discussion, and that was the end of it,” Wells said.

“Really — nobody did anything,” she added. “And a lot of this I didn’t find out until after the fact.”

State health officials declined to be interviewed for this article, but they asserted New York faced an overwhelming flood of nursing home complaints during the pandemic's initial wave in 2020.

At the same time, federal policies limited on-site inspections to curb the virus' spread and contributed to a national backlog of complaints that lingers today, officials said.

How New York responds to nursing home complaints

“Wow! That is really striking.”

Those are the first words used by Richard Mollot, executive director of the Long-Term Care Community Coalition, upon learning only about 4% of nursing home complaints were substantiated during the pandemic’s first two years.

In past years, Mollot estimated that percentage to drop as low as 10%, suggesting the pandemic-era represented a new low-point for a program long criticized by advocates and family members of nursing home residents.

“The Department of Health has a history — in our view — of not being very responsive to complaints about resident care,” Mollot said.

The new complaint data, Mollott added, underscored many New Yorkers’ concerns that visitation bans hindered outside oversight of the facilities, as well as accountability for health officials tasked with investigating complaints.

“The lack of that monitoring and oversight had frankly catastrophic impacts on residents and exasperated the dangers that they were exposed to during the pandemic,” Mollot said.

Further, the new information raised questions about far-reaching impacts of federal policies during the pandemic’s initial year. The measures, in part, suspended many nursing home inspections from March to August 2020 — with the exception of abuse, neglect, and immediate jeopardy concerns.

Another federal directive required state health officials to conduct targeted inspections of all nursing homes across the country in 2020, with a focus on catching infection-control standard violations. New York cited 62 nursing homes for violations in the initial push, resulting in a total of $328,000 in fines.

But a recent audit of New York’s effort found it was slow to respond to the infection-control crackdown, reaching just 20% of facilities from March 23 to May 30, 2020, compared with 90% in some other states.

While intended to limit the virus’ spread, the federal policies under then-President Donald Trump’s administration appear to have also contributed to a backlog in complaint reviews in New York, the new data show.

Still, many people interviewed for this article said they struggled to get nursing home complaints resolved before the pandemic. But when COVID-19 hit, those complaints seemed to disappear into a blackhole of bureaucracy, they said.

Some family members spoke of complaint hotlines going unanswered, or them being left in the dark without status updates for months. Most of them called state and federal lawmakers to report the issues, only to be referred to the Health Department or ombudsman programs, which have fewer resources and less authority than state health officials.

Many of the people also turned to political activism — and one family resorted to bribing nursing home workers — in desperate attempts to improve the care provided to the residents effectively trapped in nursing homes. Other people also decided against filing complaints altogether for fear of retribution against the resident.

In many ways, they described feeling a mix of frustration and helplessness in the face of a society that makes keeping severely ill people at home unaffordable, while failing to fix a seemingly broken nursing home industry.

What New York officials say about nursing home complaints

State health officials would not provide answers to questions about nursing home complaint statistics before the pandemic, and a public-records request for that information is pending.

In an email statement responding to questions, Health Department officials noted additional state workers were assigned to address the overwhelming number of complaint phone calls during the pandemic’s initial months, but the agency didn’t provide further details.

The state Health Department “continues to investigate all complaints received about nursing homes to determine if the allegations violate federal regulations,” spokesperson Samantha Fuld stated in the email.

“We will continue to hold providers who violate regulations accountable for their actions,” she said, adding agency policy prohibits further comment on open investigations.

The darkness of nursing home visitation bans

Jeannie Wells' mother should have been on her way out of the nursing home within weeks, following recovery from a fractured hip. Instead, her health declined rapidly and one night, aides found her on the floor.

Wells' story begins with her 91-year-old mother in the hospital in early 2020. The diagnosis called for a three-week rehab stint at The Hurlbut in Henrietta, a Rochester suburb.

Wells’ mother arrived for rehab on March 10. But two days later New York locked down all nursing homes to curb COVID-19 outbreaks, leaving Wells and thousands of other New Yorkers desperately seeking information about their relatives at long-term care facilities.

For months, the only connection between families and nursing home residents consisted of phone calls, video chats and brief in-person visits through windows. Still, Wells quickly realized her mother’s condition was deteriorating rapidly.

Then the facility abandoned the physical therapy, and everything seemingly fell apart.

“She should have been out of there, and then they called us one night [to tell us] they found her on the floor,” Wells said recently.

Unsatisfied with the answers about the apparent fall, as well as her mother’s physical and mental decline, Wells promptly filed a complaint with the state Health Department.

Over the next month, Wells remained in the dark about the agency’s investigation. She learned of the outcome in a brief call and boilerplate letter that explained the complaint was unsubstantiated.

Wells said she gained in-person access to her mother after the visitation ban ended in 2021 and fought to improve the care provided.

During one visit, Wells discovered her mother barefoot, scratching and digging at the flaking skin on her legs. The lotion Wells left at the facility for the aides to apply was buried in a bin beneath her mother’s socks, she said.

Wells had filed two additional complaints with the state Department of Health involving the conditions at the nursing home, which went unresolved for months after her mother's death in December 2021.

She recently learned inspectors deemed the complaints unsubstantiated. The outcome, she said, renewed her commitment to push for "a massive overhaul in the way we accept despicable facilities that continue to ignore residents' rights."

The Hurlbut declined to comment for this article.

From nursing home complaints to activism

The unexplained bruises. The soiled clothes, the filthy nursing home rooms.

Mary Beth Delarm's photographs captured them all.

She spent countless hours meticulously cataloging photos of her mother’s alleged neglect and abuse at New York nursing homes.

The images tracked the physical and psychological decline of her mother, Pat Ashley, who suffered from Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases.

But Ashley’s striking transformation, in many ways, is most clearly reflected in two photos: In the first she's 66, vibrant, standing beside a Christmas tree with a wide smile.

In the second, she is 91, wearing a padded helmet and a disheveled medical gown, frail and hunched in a wheelchair.

Ashley died in May 2020 of suspected COVID-19, one of many presumed COVID-19 deaths due to the lack of testing and other missing details linked to nursing home visitation bans at the time.

The second photo was taken the last day Delarm saw her mother alive.

Despite the photos she'd assembled, Delarm said authorities failed to penalize the Diamond Hill Nursing and Rehabilitation Center in Troy for several health and safety violations — both before and during the pandemic.

“They weren’t paying attention,” she said recently, recalling how she contacted the state Health Department twice a week in early 2020 to report violations but often gave up after phone calls or emails seeking status updates went unanswered.

“During COVID you couldn’t really speak with anybody because they were bombarded,” she added.

Now, Delarm displays the photos of her mother’s decline on posters, periodically joining hundreds of other New Yorkers at rallies in Albany. They gather, unified, to demand lawmakers overhaul the nursing home industry.

“If these people are not held accountable and fined in some severe way, we’re going to keep seeing people getting neglected, abused and killed in nursing homes,” said Delarm, who's become involved with the Elder Justice Committee of Metro Justice.

Delarm described filing allegations against several nursing homes spanning malnutrition, over-medication, physical and verbal abuse, unsanitary conditions and neglect.

While at least one pre-COVID-19 case resulted in a fine, Delarm said, many other complaints resulted in unsubstantiated findings or remain unresolved years later.

Still searching for answers and justice, Delarm reeled off details of the complaints. The seemingly urgent threats to her mother’s safety raised questions about how regulators responded to the case.

She remembers finding her mother sitting in wet clothing and discovering sores on her body. Repeatedly. She'd buy new clothes that would disappear. Her complaints lingered, unresolved.

Once, as she stood outside her mother’s room, she heard an aide threaten the elderly woman.

“She screamed at my mother, ‘I told you to lay your ass down and if you get up again, you’re going to be in trouble,’” Delarm recalled. “I couldn’t believe it and went down and complained, but nothing came of it.”

Today, Delarm wants protection for those going through what her family did.

“I’m not interested in after the fact; I’m interested in getting the law enforced and having accountability,” she said.

Collar City Nursing and Rehabilitation, the new name of the Diamond Hill facility, did not respond to requests for comment.

Families file lawsuits in pursuit of answers

Theresa Sari’s mother suffered repeated falls and injuries at a New York nursing home before COVID-19 hit in 2020, triggering an odyssey through the complaint process and court that lingers years later.

Sari first complained to the state Department of Health in November 2018, but the filing went unresolved for months. Evidence collected by Sari, however, suggested her dementia-plagued mother’s fractured hip and dislocated shoulder warranted urgent action by regulators.

But Sari’s fight to protect her mother changed forever on April 1, 2020, when then 60-year-old Maria Sachse contracted COVID-19 at The Grand Rehabilitation & Nursing at South Point on Long Island.

Banned from visiting, Sari frantically called the nursing home repeatedly for updates on Sachse’s condition. Often, a response never came from the facility, she said. Sachse was soon transferred to a hospital and clung to life while on a ventilator, dying April 13, just shy of her 61st birthday.

While skeptical of its worth, Sari filed another complaint on April 17 with the Health Department related to the COVID-19 death.

Awaiting action on the complaints in 2020, Sari mourned her mother, a fighter who survived life-threatening surgeries for a severe cleft lip and palate as a child, only to face a rough life in poverty, raised by a single mother in Hell’s Kitchen.

“Even in the end, she was the light of my life,” Sari recalled recently, adding Sachse “loved to laugh, sing and dance when she was younger.”

And by early 2021, Sari circumvented the Health Department inaction and sued the nursing home, alleging negligence and other wrongdoing linked to her mother’s death.

Now, Sari’s case is among dozens of other lawsuits filed against nursing homes nationally during the pandemic. Many of the cases have slogged through the courts, as some nursing homes claim COVID-19 liability protection linked to pandemic-era laws passed in 38 states.

In New York, lawmakers and former Gov. Andrew Cuomo enacted a liability protection law for nursing homes and health care facilities in April 2020. It was repealed in March 2021 and court battles are still raging today over how that applies to lawsuits filed before the repeal.

Further, nursing home complaints that remain unresolved potentially complicate the issue, as people awaiting action by regulators could struggle to file lawsuits within the statute of limitations, typically two to three years in most states.

The Grand Rehabilitation & Nursing at South Point did not respond to requests for comment.

'I've heard nightmares all over the country'

Ana Martinez was expected to be in a West Islip nursing home for about four weeks after her knee surgery. It turned into three months because of insurance red tape and struggles to find home care.

Then, before she could leave Our Lady of Consolation Nursing & Rehabilitative Care Center, the pandemic hit and “she basically got caught in the facility,” said her daughter, Vivian Zayas.

Zayas initially thought the nursing home would be a safe place for her mother during the pandemic, but she became concerned when her mom stopped answering her phone, which was unlike her.

Zayas and her family received no notification when her mom initially started having COVID-19 symptoms.

Despite showing signs of illness, staff told Zayas her mother could go home — because she was having trouble breathing, they said, she could take an oxygen tank. But Zayas pushed back. Her mother would be alone in her apartment. Who would monitor her oxygen? Besides, she didn’t go into the nursing home with an oxygen tank — why would she leave with one?

Staff said they could do an X-ray, but they later called to tell Zayas they were sending her mother to the hospital because of her breathing.

Martinez died two days later at the hospital.

“I just never suspected that a knee surgery would end up in us holding a jar full of her ashes,” Zayas said.

Devastated, she and her sister started asking questions. But no one was listening.

"Once your loved one dies, it’s like they shut the door and you have no access really to inquire,” Zayas said.

A lawsuit Zayas filed against Our Lady of Consolation over her mother’s death is ongoing in Suffolk County Supreme Court. USA Today Network's requests for comment from the nursing home were not immediately returned.

Zayas and her sister also started connecting with other families who encountered similar problems. They shared their story publicly and soon founded Voices for Seniors, a nonprofit advocacy group for seniors and their families.

Now they help people navigate their options when faced with nursing home concerns. That includes helping them file complaints with the Department of Health, which Zayas said many people don't know to do.

“I’ve heard nightmares all over the country,” Zayas said. “We’ve realized this is not a new issue.”

A similar awakening led Serge Kingery to join a family council group advocating for improvements at the New York State Veterans Home at Montrose, Westchester County.

Kingery, a 65-year-old Navy veteran, described being most frustrated by the lack of transparency his 91-year-old father’s nursing home provides to families.

Kingery has filed nine complaints with both the Health Department and veteran’s home where his dad has lived for a year and eight months.

One complaint involved not being notified that someone on his father’s floor tested positive for COVID-19.

Kingery had taken his dad, a Vietnam veteran, out for a five-day visit with family. While his dad was out, someone on his unit at the nursing home tested positive, but Kingery and his dad never got a call.

Kingery said if he knew someone on his father’s unit had COVID-19, they would have taken precautions.

When Kingery returned his father to the nursing home, he got a call saying his father tested positive.

USA Today Network's requests for comment from state health officials on Kingery's dad's experience were not immediately returned.

Kingery still has two grievances open. It takes months to hear back about them, and the responses from the Health Department are the same — that they didn’t find any violation of state or federal regulations, but that they will add the allegations to a complaint profile for the facility that will be reviewed.

“Nobody wants to write grievances,” Kingery said. “Just answer the questions.”

As a veteran thinking about his own future, he added: "I'm the next generation going in."

A nursing home resident’s story

At first, it seemed that Thonna “DeDe” Cappellino Stapert's stay at Canandaigua's Ontario Center for Rehabilitation and Nursing would be uneventful.

That all changed only a few weeks later.

The 79-year-old was bedridden and diapered while she recovered from surgery. At the beginning, someone would come in during the night to change her diaper. Around 7 a.m. they would get her ready for breakfast.

Then the nighttime visits stopped. By the last two weeks of her two-month stay there, she said, she was taking care of herself as best she could.

For nearly three months — from Jan. 6 to March 3 — she had three showers.

Even worse? The food.

“I met with the chef three times personally and told him I wouldn’t feed that food to my dog,” said Stapert, a Rochester area resident. “The food was atrocious. Sometimes it was just unidentifiable.”

A meal might include a scoop of stuffing and a scoop of potatoes but no turkey. She enjoyed hot dogs and was able to have them often — except that what she received there were barely recognizable as hot dogs and they were always cold, she said. Every morning for breakfast Stapert received cold oatmeal, cold coffee and juice. And she rarely had the same meals as the other resident.

Getting an aide to come to her room was also a challenge. Stapert said she might lay there for five hours waiting for someone to help her up from bed or sit for the same amount of time in her wheelchair.

“I just kept hearing they didn’t have enough staff,” she said.

Once she was able, she started taking care of herself, she said. The final straw came one Sunday morning when she stripped her bedding but then couldn’t get anyone to come and finish making it, a job she really couldn’t have done herself.

But there was one thing she could do.

“I called my daughter and said I had to leave,” Stapert said. “It was a horrible experience, and I hope I never have to go back there.”

The facility’s Spokesperson Jeff Jacomowitz said Ontario Center had multiple staff members present on the overnight shift during the time period described and the facility’s food service director met with Stapert to discuss her meal preferences on multiple occasions. He pointed to a number of benchmarks that he argued placed the facility above others in the state and nation, including the ability to regain mobility among Ontario Center’s residents.

“Ontario Center in Canandaigua, New York meets the requirements set forth by the New York State Department of Health in terms of staffing, sanitary and dietary needs for its residents,” Jacomowitz noted.

Stapert confirmed that she met with the cook three times, and said she only saw one staff member on her floor during the overnight shift. She has started an official complaint against the facility with the State of New York, she said.

Share your story

Have you or a loved one had a bad experience at a New York nursing home? Do you have an unresolved nursing home complaint with New York state, or a question about how to navigate the complaint process?

Fill out the form below, and a USA Today Network reporter may reach out to interview you and include your story in future coverage.

David Robinson is the state health care reporter for the USA TODAY Network New York. He can be reached at drobinson@gannett.com and followed on Twitter: @DrobinsonLoHud

Diana Dombrowski covers Yonkers for The Journal News/LoHud.com. Contact her at ddombrowski@gannett.com. Follow her on Twitter at @domdomdiana

Mike Jaquays is the community news reporter for the Mid-York Weekly. Email him at mjaquays@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on New York State Team: NY nursing home complaints filed during the pandemic are unresolved