She was a geriatric nurse. Why did it take Delaware so long to realize she was neglected?

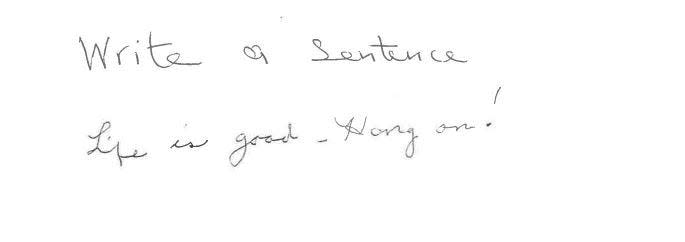

Months before it all went wrong, Mary Claudia Jones Barthelmeh clutched a pen and wrote in cursive:

“Life is good – Hang on!”

It had been a hard few weeks for the 96-year-old. She suffered a fall, requiring 19 staples to her head. Previously only needing help with the stairs, she now was unable to walk more than 28 feet by herself, documents show.

But Barthelmeh, who always preferred if you called her Claudia, was doing her best to keep positive, even when writing a sentence as part of a cognitive health exam.

It was September 2020, months into a pandemic that cut off her connection to the outside world. No more family visits at Dover Place, the assisted living facility in Delaware she now called home. No more themed parties where she dressed up and laughed with her friends. Now, she was mostly confined to her room.

Claudia tucked the invitation to her grandson’s upcoming wedding in her purse so it would be with her at all times. Her blue gown for the occasion hung in the closet for months. She couldn’t wait until she was vaccinated.

Two weeks after this exam, on Sept. 25, 2020, medical records noted that Claudia had redness and shearing to her big toes. This soon became pressure ulcers which soon became infected, quickly exceeding the limit of care an assisted living is allowed to provide.

By February 2021, Claudia was hospitalized for her wounds, the severity of which was a shock to her family.

She died two weeks later.

Granddaughter Candace Esham filed a complaint to the health department one day after Claudia’s hospitalization. Complaints are often the only tool Delawareans have to seek accountability for the care loved ones receive in long-term care facilities.

MORE COVERAGE: Delaware struggles to investigate nursing homes, assisted living facilities. What to know

But for families like Claudia’s, it can lead to little recourse.

Unlike nursing homes, assisted living facilities have no federal oversight. It’s up to the state to regulate, which can result in a patchwork of accountability.

Delaware’s Division of Health Care Quality, which is supposed to be a state watchdog for these facilities, has struggled for about a decade to investigate complaints – particularly for assisted living facilities. A Delaware Online/News Journal investigation found:

The division has about 1,500 complaints for nursing homes and assisted living facilities in its backlog. Data analyzed by The News Journal shows that since 2013 assisted living complaints are overall often investigated less than nursing homes.

The state has chronically struggled with hiring and retaining staff to investigate these facilities, in part because of low salaries. The division has asked for additional funding in recent years but has been denied by the governor’s office.

Dover Place, at various points, did not inform Claudia’s family or her physician about the severity of her wounds, as well as declined to send her to the emergency room that November when the infection worsened. Before the state investigated Claudia’s complaint, Dover Place had already been cited for neglect twice in 2021.

It took the state’s Division of Health Care Quality more than seven months to acknowledge the complaint submitted by Claudia’s granddaughter, according to emails and documents reviewed by The News Journal.

The family’s mission to find answers – and closure – would take even longer. Dover Place’s parent company, Enlivant, declined to comment for this story, citing privacy concerns.

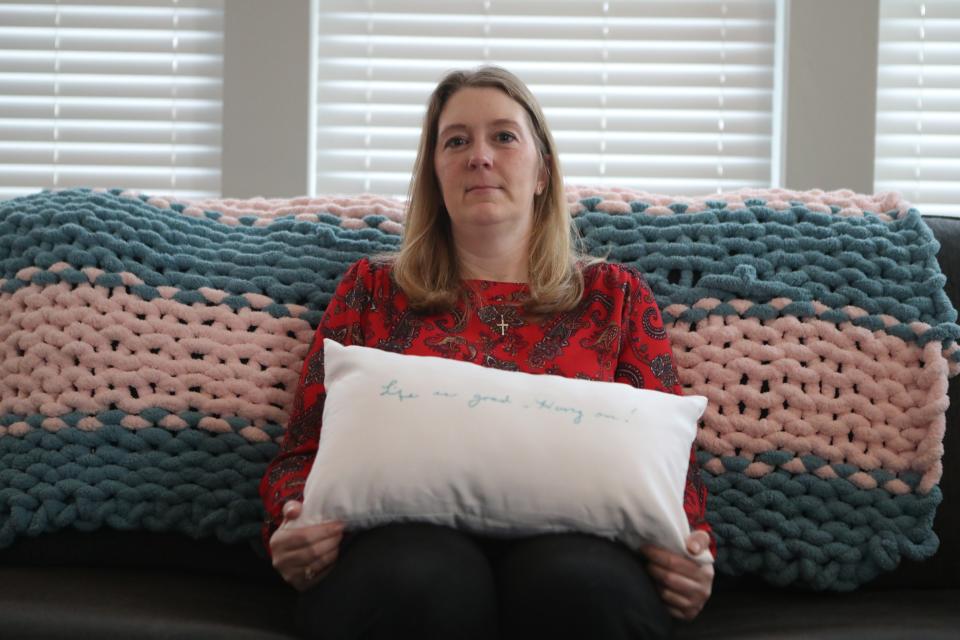

In the fog of grief, Candace still returns to the sentence her grandmother wrote months before she died. She now has “Life is good – Hang on!” embroidered on a pillow. She keeps it in her bedroom.

“She was not ready to go,” Esham said.

How Claudia came to call her assisted living home

It was the mid-1940s and the Georgia farm girl had to find her own way to the train station. No one in her family thought she was smart enough to go to college and refused to help her get there.

So, Claudia called a taxi to take her to Emory University. After earning her college degree in nursing came a brief professional modeling stint in New York City. The marriage and death of her first husband, and then the marriage of her second and third. Children and grandchildren.

In her 50s, Claudia returned to nursing full-time. She worked at the state-run Hospital for the Chronically Ill in Smyrna. Her family poked fun at how she was older than some of her patients. Two decades later, filet mignon and crab cakes were served at her surprise retirement party.

Claudia made the decision to enter an assisted living facility at age of 90 after her third husband of 21 years died. Soon, Dover Place became home.

Assisted living facilities have seen explosive growth here in Delaware and throughout the country. They are different from nursing homes in terms of the level of medical care, assistance with daily life and the setup of one’s living quarters. Assisted livings often resemble home-like environments, where people tend to live more independent lives.

Claudia did her hair and makeup each morning and played cards late into the night with friends. She enjoyed doing Tai Chi and Wii bowling. She followed the Phillies closely, noting the game’s score on the right-hand corner of her diary each day during the season.

Lucilla Esham and her two adult children visited a couple of times each week. It was to both visit Claudia and to keep a watchful eye.

When the COVID-19 virus began spreading in March 2020, attacking long-term care facilities first, the state and federal governments forced the facilities to close their doors to visitors. Claudia and other seniors were isolated in their rooms for weeks.

In the early hours of Aug. 26, 2020, Claudia fell in her room. She suffered a lacerated spleen and needed 19 staples in her head, her family said. When Candace Esham visited her in the hospital, Claudia asked for her help to apply lipstick – an encouraging sign. Maybe she would be OK.

INVESTIGATIVE REPORTING: They thought their mother was safe in her nursing home. Then their worst fear came true

In September, three weeks after Claudia returned to Dover Place, a nurse from Bayada Home Health Care, a skilled nursing agency, noted in medical records that Claudia has redness and “shearing” to her big toes.

Documentation shows that an ointment was applied to Claudia’s toes twice a day for the next two weeks. But during this time, the facility had not informed Lucilla Esham, the medical power of attorney, about her mother’s new wounds, according to a state report.

The toes, by late October, became infected, according to records reviewed by The News Journal. A “bloody sanguine discharge” was coming off from the tips of her toes. Claudia began to take an antibiotic for the infection.

Nearly one month later, on Nov. 17, a Bayada nurse wrote that Claudia’s right big toe was red and raw. Dead, black tissue was beginning to take over. The nurse wrote she was sending her to the emergency room for an evaluation.

A Dover Place employee, according to this Bayada nurse’s note, called Lucilla Esham to tell her that Claudia would be going to the ER.

But then the plans changed. Claudia was never sent.

According to a state inspection report, a nurse practitioner decided to keep Claudia in assisted living, opting to do blood work and start her on another course of an antibiotic. The report cited the Bayada nurse’s note.

Lucilla Esham remembers receiving this call. She remembers a Dover Place official informing her that the facility planned to take her mom to the ER, which she said she supported. But she also remembers a call a few hours after, in which the same employee told her the facility decided to keep her.

Lucilla Esham said she didn’t question it, thinking Dover Place knew what was best.

In the state investigation report, one Dover Place official said it was Lucilla Esham who did not want her mother to go to the ER – a point Lucilla Esham ardently disputes.

When the state interviewed the nurse practitioner mentioned in the nurse’s note, she told the state that she did not have “any special training in wound care,” instead relying on home health care skilled nursing agencies – of which Bayada is one – for recommended treatment.

A Bayada spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

“With regard to the 11/17/20 decision to not send (Claudia) to the hospital for an evaluation of the deteriorating wound,” the state report reads, “(the nurse practitioner) stated she would have to review her notes and follow up with the surveyor.

“No additional information was received by the surveyor.”

Claudia continued to have issues with her toes in the beginning weeks of 2021, according to medical records. In early January, her injuries appeared to have healed. But then the wounds opened up again by the end of the month.

There was “no evidence” that Claudia’s physician and daughter were both informed of the new injuries, the state would later find.

On what would become her final day at Dover Place, Claudia donned a purple, shimmery pantsuit for the Mardi Gras party the facility was hosting. It would also be the outfit her family chose to bury her.

Instead of attending the party on Feb. 4, 2021, Claudia was admitted to Bayhealth. Redness ran up her right leg into her mid-calf. Her second toe was red and purple. It later fell off in her hospital bed, her family said. Doctors told the family Claudia’s toe would likely have to be partially amputated.

The next day, according to emails provided to The News Journal, Candace Esham submitted a complaint to the Division of Health Care Quality. She felt her grandmother was neglected and worried it would happen again – or to another resident.

This will all be taken care of quickly, Candace Esham told herself. She thought her grandmother was going to live through this. But she became the last person to see Claudia alive.

Candace Esham held her grandmother’s hand in the hospital even though her grandmother was no longer able to squeeze it.

Claudia died on Feb. 16, 2021. The cause of death was sepsis, her family said, the result of an infection that had spread to her blood.

In the days after, Lucilla and Candace Esham had phone calls with state investigators who they said told them the complaint was going to be made a priority. One investigator, Lucilla Esham said, mentioned how she knew Claudia from her time at the Hospital for the Chronically Ill.

But months went by – and nothing.

Delaware has struggled with long-term care surveyor vacancies for years

The Division of Health Care Quality, one of the smallest divisions in the state’s health department, is responsible for regulating healthcare facilities, particularly the nearly 80 nursing homes and assisted living facilities.

But the division does not have enough surveyors to inspect them.

“The number of facilities keeps growing, but unfortunately our staffing numbers aren’t growing with that,” Corinna Getchell, division director, told a legislative task force in late March 2023.

Since fiscal year 2020, the division has requested a total of $1.67 million in additional funding, particularly for the completion of annual and complaint surveys. But it has only been allocated $153,600 in Gov. John Carney’s recommended budget. This occurred in fiscal year 2021.

For the upcoming fiscal year, the division asked for $851,700, which would specifically go toward hiring contractors to conduct complaint and survey inspections. It was the division’s only request and was denied by the governor’s office, according to recommended budget documents.

When lawmakers asked about this during the health department’s budget hearing, Office of Management and Budget Director Cerron Cade said the administration has added this to its “wish list” in the event new revenue comes in this spring.

“If we had unlimited resources and the ability to just grow their operating budget all at once this year,” he said, “we would have taken advantage of it.”

The state’s low salaries, particularly in a competitive market desperate for nurses, have made it hard to attract people to the division. The General Assembly did increase wages for the health department last year, which went into effect last July. But it hasn’t been enough.

Getchell, the division director, told The News Journal that a number of people have declined job offers from the state because they were able to receive a higher salary elsewhere.

In August 2022, vacancy rates for long-term care surveyors hovered around 50%. Of these employees, half had been there under five months, Getchell said during a legislative task force meeting. Three of these employees had been employed for a week.

As of March 2023, the overall Division of Health Care Quality vacancy rate was 10%, state officials said. The vacancy rate for long-term care surveyors was 14%.

The base requirement for a long-term care surveyor is to be a registered nurse. Then, additional training is required. A surveyor needs to shadow an employee for an extended period of time, which has become one of the biggest barriers for the division.

State officials said 38% of full-time surveyors are able to “complete the federal nursing home process.” One seasonal employee is solely focused on assisted living surveys. But full-time surveyors can complete both assisted living and nursing home inspections.

Health Secretary Molly Magarik acknowledged at a February 2023 budget hearing that the state does not have enough employees to investigate complaints. As a result, the state is also not in federal compliance.

“We're doing what we can to meet as much of the federal requirements as possible and then having very candid conversations with the federal government about where we are,” she said.

“Part of what we're hearing back is: ‘Delaware is not alone in this crisis.’”

Mary Peterson, former DHCQ director, said the division was underfunded during her tenure from 2013 to 2019. She said at every legislative budget hearing she would ask for more funding to complete inspections − but she was repeatedly denied.

“DHCQ has just not been able to keep up with the demand and what needs to be done,” Peterson said. “And unless the state steps forward, and gives them more positions and pays the people the appropriate salary, it ain't gonna happen.”

As a result, the division struggled to juggle the number of complaints being filed on top of its other regulatory tasks, Peterson said. In 2013, she said there was a complaint backlog of about two years.

In order to get a “good handle” on complaints, she said, the division had to “ignore other things” – including annual inspections of assisted living facilities.

“Even when I retired,” she said, “it still kept me up at night.”

A backlog of 1,474 uninvestigated complaints

For the past decade, Delaware has struggled to manage its backlog of complaints for both nursing homes and assisted living facilities.

And when these complaints are investigated, those for nursing homes are investigated at a higher rate than assisted living facilities, according to News Journal analysis.

The state triages nursing home and assisted living complaints the same way: A complaint, which can come via an online form, the phone hotline or fax, is triaged by state nurses. Some complaints don’t rise to the level of the state needing to investigate.

But more serious allegations – particularly those involving abuse, neglect or mistreatment – are sorted into different categories depending on their severity. The federal government has specific requirements for how quickly states need to respond to certain nursing home complaints.

The pandemic forced the Division of Health Care Quality to focus mainly on COVID-19 infection control inspections and immediate jeopardy complaints, which are the most serious, for the first year of the pandemic.

Getchell, the division director, said the state would still investigate complaints “off-site,” which surveyors would conduct interviews on the phone or via Zoom. Still, the change in priorities added to the backlog.

The backlog, Getchell said, consists of complaints that fall under the 45 day or older categories. They include those those reported by Delawareans and those reported by the facilities themselves.

Despite the backlog, Getchell said the state still investigates the most serious complaints in a timely fashion.

But Delaware has a history of not investigating the most serious complaints quickly enough. A September 2020 federal report from the Office of the Inspector General found that Delaware was one of 10 states that failed to meet Medicare’s performance threshold for timely investigation of high-priority nursing home complaints every year from 2011 to 2018.

This report did not include information about assisted living since the facilities are not regulated by the federal government.

Data, which The News Journal obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, showed nursing home complaints have a higher inspection rate than assisted living facilities.

Getchell acknowledged this in an interview. Unlike for assisted living, the state is required to meet certain timeframes by the federal government for nursing home inspections. The state is also dependent on the federal funding it receives.

From 2013 to 2021, an average of about 22% of the assisted living complaints filed were investigated by the state each year. Nursing home complaints, in comparison, had an average investigation rate of about 49% in that time period.

Getchell was not sure how long it would take to clear out the backlog. A lot of it depends, she said, on staffing.

“I know the number sounds horrible,” Getchell said of the backlog, “but the surveyors are working as hard as they can.”

'We were able to verify concerns'

In late September 2021, Candace emailed Getchell, asking about the status of the complaint. It had been seven months. Getchell responded on Oct. 4, confirming the complaint was received.

Getchell wrote in the email, obtained by The News Journal, that the Division of Health Care Quality was still making its way through its backlog of complaints that were not triaged as immediate jeopardy. Staffing, she explained, had also taken a hit.

She wrote that the survey team was “not yet operating at full capacity.”

Days later, Lucilla Esham, Claudia’s daughter, received a phone call from a state compliance nurse. She said she was told the complaint was being closed “because the workers at Dover Place said nothing happened.”

Lucilla Esham was floored. Why would you trust what they say, she thought. She asked if the nurse reviewed her mother’s medical records, as she and her daughter Candace had sifted through the documents looking for answers.

The compliance nurse, Lucilla Esham said, told her they had not. State officials declined to answer questions relating to the complaint filed by Claudia’s family.

Lucilla Esham pushed back, urging the state to obtain her mother’s medical records. An email from the investigator’s supervisor confirmed on Oct. 12, 2021, that the state had now obtained the medical records and a new complaint had been filed.

The state investigated the care Claudia received in the final months of her life on Nov. 17, 2021 – 285 days after Candace first contacted the Division of Health Care Quality.

“As a result of our investigation,” according to a Dec. 27 letter addressed to Lucilla Esham, “we were able to verify concerns related to care with violations in the area of neglect as well as other facility violations.”

But this wasn’t the first inspection Dover Place failed in 2021 − it was the third. All three times, it was cited for neglect.

A year of three failed inspections

Just one month before Claudia was hospitalized, Dover Place failed its first state inspection of the year.

The coronavirus was still raging in January 2021, with many long-term care facilities struggling to combat the virus while juggling the constantly updating state and federal guidelines.

Surveyors conducted a COVID-19-specific inspection on Jan. 6, 2021. Dover Place was cited for neglect, specifically failing to pay “attention to the physical needs” of two residents with COVID-19. For one of these residents, who also had dementia, there was no evidence Dover Place contacted their physician.

Ten months later, on Sept. 30, 2021, Dover Place faced another instance of neglect, according to the inspection report. In July, a resident who had dementia found his way outside and walked down a street. An employee driving to work spotted him.

A health surveyor stepped into Dover Place for a third time on Nov. 17, this time to investigate the concern Claudia’s family raised.

The report revealed that in October 2020, Claudia was suffering from an “unstageable” pressure ulcer on her big left toe. This occurs when there is so much tissue loss, the depth of the ulcer could not be determined because of the amount of dead tissue. She had a stage two pressure ulcer on her right toe, in which skin blisters from an open sore.

The wounds likely started from the pressure of the shoes Claudia was wearing, according to the report.

One of the overarching issues, the state found, was that Dover Place “failed to ensure attention to the physical needs of the resident” when these injuries were discovered in September 2020. The facility failed to follow its policies for skin and wound care, as well as when a resident has a change in condition.

Because of the severity of her wound, the assisted living facility was required to submit a waiver to the Division of Health Care Quality. It never did, according to the report.

TELL US YOUR STORY: Do you have an experience with Delaware assisted living facilities? We want to hear them

Assisted living facilities are limited in the types of conditions they can care for, said Peterson, the former DHCQ director. Dover Place’s interim nursing home administrator said in the inspection report that she was unaware of Claudia’s condition, which is why the waiver was never requested.

Regulations, according to the report, state that assisted living facilities are not allowed to provide care to residents who have developed three or four skin ulcers.

Peterson, who reviewed this report, said state officials taking nine months to investigate this complaint “seems like a long time to get in to check on whether or not there was anybody else” in Dover Place affected by this issue.

This type of wound “should not have been treated in an assisted living,” she said.

The inspection found a breakdown in communication, with the care services manager and nursing home leadership repeatedly not being aware of Claudia’s wounds. The report also detailed how Dover Place failed to notify Lucilla Esham, who was Claudia’s medical power of attorney, about her mother’s worsening condition.

Claudia’s physician was also not notified at key points. When a podiatrist called for a medical boot to be ordered, there was a lack of evidence that happened, according to the report.

In its plan of correction, the facility noted it had educated staff on state regulations and plans to undergo regular audits to make sure the facility is in compliance. Nurses will also receive pressure injury training.

But it also included a disclaimer in the beginning, in which Dover Place did not appear to acknowledge wrongdoing.

It reads: “Submission of this response and Plan of Correction is NOT a legal admission that a deficiency exists or, that this Statement of Deficiencies was correctly cited, and is also NOT to be construed as an admission against interest by the residence, or any employees … who drafted or may be discussed in the response or Plan of Correction.”

Peterson found that to be alarming. She said she would have never approved something like this. It raises the question, she said, of how Delaware can have strong oversight when it allows facilities to deny wrongdoing.

“For them to tell me that they're not admitting that a deficiency exists,” she said. “No, no, no.”

Getchell, the current director of DHCQ, said the disclaimer on Dover Place’s plan of correction has been “addressed." The division is not “allowing these statements on plans of correction” going forward, she said.

She did not comment on how or why this disclaimer appeared in the report in the first place.

'See you later. Love to each of you.'

In the last line of Claudia’s will, she left a message for her family: “Don’t be sad. I’ve had a wonderful life and a loving family. See you later. Love to each of you.”

It would be the hardest request for her family to fulfill. After Claudia died, daughter Lucilla Esham tossed and turned at night, wrecked by the guilt of how her mother died. Echoes of Claudia’s screams while in the hospital are now heard in granddaughter Candace’s nightmares.

Members of the family have become estranged over differences on how to hold Dover Place accountable. This would have gutted Claudia, her daughter said.

Even though Claudia worked at a state nursing home for 20 years, her daughter and granddaughter regret her spending her final years in a long-term care facility. They now want to prevent other families from similar pain.

“Our trust was destroyed,” Lucilla Esham said, “and her life was taken.”

They have turned to advocacy, researching a Medicaid program called “Community First Choice,” which provides long-term care to people in their homes. A handful of other states have adopted it, including Maryland. The Eshams have started to discuss this program with lawmakers.

Lucilla is still going through all of Claudia’s belongings, each box teaching her something she never knew about her mother. Journal entries from her final years also confessed how deeply lonely she was, thoughts she never shared with her family. Lucilla Esham said her mother wrote in her diary about how she went days without someone helping her get dressed or take a shower.

Lucilla Esham also uncovered Claudia’s term papers from nursing school and photos from her modeling days. Claudia made a scrapbook before she left the Hospital for the Chronically Ill, filling it with photos of residents and staff.

Tucked in its pages is a poem called “Crabbit Old Woman,” depicting an elderly woman’s final days.

The last stanza reads:

“I think of the years, all too few, all gone too fast

And I accept the stark fact that nothing can last

So open your eyes nurses, open and see

Not a crabbit old woman, look closer – SEE ME!”

Contact Meredith Newman at mnewman@delawareonline.com or at 302-256-2466.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Delaware assisted living complaints leave backlog with tragic results