She had it better than most Arizona prisoners but says she still faced racism and labor abuse. 'I don’t think I’ll ever forgive them'

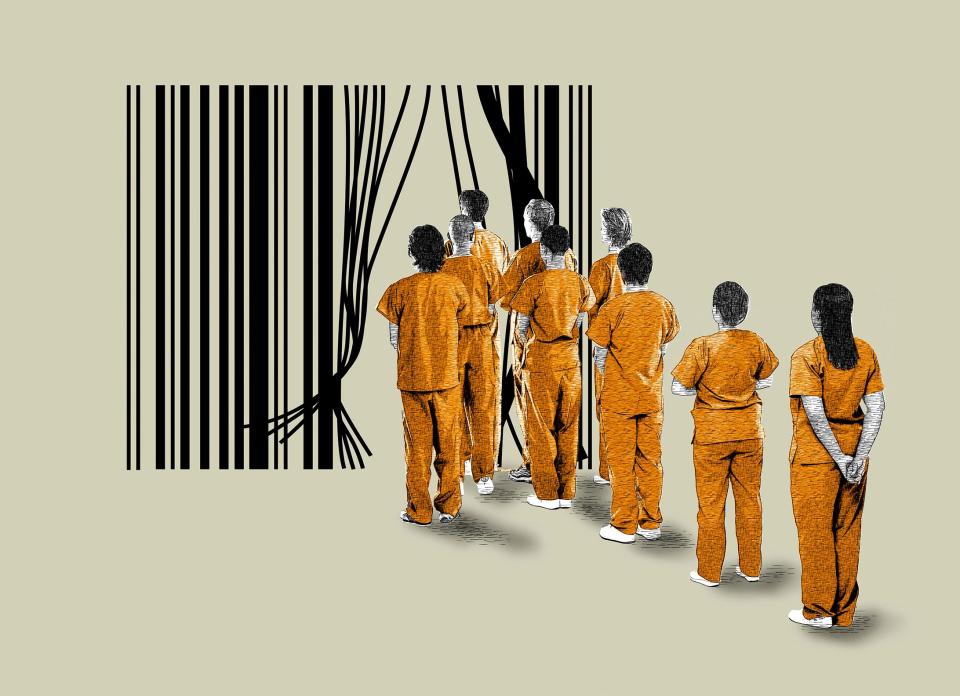

Lola N’sangou went through the process that countless other women have gone through within hours of being placed into a prison: Corrections officers searched every part of her body, forced her into a uniform of bright orange clothes, white socks and stiff, fake-leather boots.

For three weeks, she popped between blood tests, drug tests, and mental health screenings. The exams were innocuous enough; They were created to assess if the prison needed to place N’Sangou somewhere with more security, more lockdowns, more officers, and (more often than not) more violence. The other option was a part of the prison that was somewhat safer, with less security and less worry of a fight or an internal scuffle.

But before they settled on where she lived, they had to figure out where she would work.

Beyond assessing her physical and mental health, the Arizona Department of Corrections began quizzing her on her job history and education. Before prison, N'sangou had a short-lived career as a firefighter and a longer career as a wedding planner at a five-star hotel in Phoenix.

Still, even with her college education, she was nervous when taking the test: Her life had been upended, and she was away from her child, her home, and her family. She lived in a prison that she had to learn to get used to — not just mentally, but also physically. Prisons are notoriously cold, and the prison-issued blankets don’t provide warmth; clothes aren’t known for their comfort; shoes don’t provide support; jumpsuits are worn down in some cases so much that women described them more as chiffon than cotton.

N’sangou was uncomfortable and anxious about being in prison — top of mind for her wasn’t taking a math test.

This test, though, was different. It didn’t have to do with her crime, or her mental health. It didn’t have to do with her physical well-being or her ability to manage different rehabilitation programs. Instead, it was a test to see where she would be most valuable to the prison. The results meant the difference between working for the state in a bad job or a worse one.

The test would have been basic for a young student, or someone who had just left high school or even college: Can you calculate percentages? Can you find the adverb in a sentence? What is passive voice?

Had N'sangou been out of school any longer than she had, or a job where she didn’t need to know many of these basic — and arguably unneeded — formulas in her head, she said she could have failed. (Later in her prison life, she said she met people with advanced graduate degrees who failed the tests and were forced to undergo months of middle school and high school education before they could do anything meaningful with their time locked up.)

Nervous throughout the testing, a staff member eased her concerns. Because her crime was a car accident that resulted in someone being killed, the prison considered her a violent offender, and she would be placed in a higher custody facility. But while the employee finalized N'sangou’s scores, they informed her she scored the highest scores possible, and was going to be special.

She was handed her first work assignment and remembered the staff member telling her: “Once you hit the yard, you need to go work in education.”

‘Not for human consumption’

Just east of Loop 303 where it crosses Interstate 10, planned home communities blend into the background of dusty and brush-filled mountain ranges.

To the people who live here, it’s well known that a highway separates them from the Perryville women’s prison. Drive westward, and civilization ends for another 100 miles.

From N'sangou’s vantage point, she didn’t stay fixated on life beyond the highways that are barely visible from some cell windows. She was serving a 12-year prison sentence and wanted to stay focused and productive with her time.

But that proved difficult, especially working as a teacher’s aide for someone whom she described as being “zoned out.” The role was teaching middle-grade classes to people who were sometimes in their 40s and 50s or who simply didn’t want to be taught.

N'sangou recognized these prisoners for who they were: people who just wanted to be left alone and do their time in peace, without the burden of trying to learn just for learning’s sake. Because she was in a maximum security yard, some of the women in her classes were lifers who thought that their time in prison learning math skills would take them nowhere closer to being uncaged.

But there were others who wanted the education, and squeezed N'sangou tight with big hugs when they finally passed their exams. For them, an education meant a possible opportunity.

And the prison also saw a benefit in them getting their education: It meant they could be put to work.

For N'sangou, she quickly learned the importance of work, and that the impressions she had about prison — that food, clothing and rent were all provided — were all wrong. She realized she wasn’t going to be left idle in her cell for years, or put into rehabilitative programs, or even placed into work that would focus on expanding her already employable skill set. She had to work where the prison said she’d work, or she’d be unable to buy basic necessities.

Denim jeans, hot food, deodorant, or bras are not guaranteed in prison. Inside, prisoners typically receive their uniform, utensils for food, a thin cotton blanket, a pair of heavy pleather boots with no insoles, a pair of used socks and a plastic pair of slippers. For her entire time inside, that was all N'sangou would receive. If her clothes or boots wore out, in theory, they would be replaced. But she'd need to buy anything else, and pay to replace lost or stolen items.

The prison-issued boots didn’t protect her feet or offer any kind of arch support. N'sangou was a runner, and she knew that exercise was paramount to keeping her mental health good while in prison. But she couldn’t reasonably run in heavy boots. And she couldn’t imagine wearing boots every day for over a decade. And when reporting to some assignments, officers sometimes didn’t want prisoners to wear them.

Sneakers were a necessity.

To afford them, N'sangou would have to forgo the “zoo-zoos and wham-whams,” the term prisoners give to sweet items they could buy from the prison store, such as honey bun pastries or other vending machine-like foods.

Even though prisons serve three meals a day, they come at your own risk. Prisoners have shared photos and describe being served chicken packaged in boxes labeled: “Not for human consumption.” Small plastic or metal shards are not uncommon objects found in oatmeal. Bread is often moldy or wet.

Occasionally, the prison provided toilet paper, and some sanitary napkins — the kind that don’t absorb any amount of blood, and simply shift around in undergarments. Anything else, including food, other hygiene supplies, or any other small comforts such as a clean pair of socks, had to be purchased from the prison store.

Because N'sangou had a job, she wasn’t considered an indigent prisoner — the classification a person gets when they don’t make enough money to buy items, so they receive a certain number of products, including stamps, shampoo, or clothing for free.

Whenever N'sangou needed soap, or toothpaste for her sensitive teeth, or a pair of underwear, she needed to buy them. Commissary menus gathered from prisoners by The Arizona Republic showed that items are comparable in prices to the outside.

But N'sangou, even with a promotion working at the prison commissary store, was making just 45 cents an hour, only 10 cents more than what she was making as a teacher’s aide. Prisoners still make similar amounts today as they made 10 years ago, according to pay scales shared by the Department of Corrections to The Arizona Republic.

A single pair of New Balance sneakers, as of a commissary menu from last year, cost $44.

With deductions, someone like N'sangou would have to work two full months to afford a pair.

‘They don’t hire Black girls’

N'sangou didn’t get into much trouble while at the higher security yard, Lumley. But that wasn’t unusual for her. Even though she had made a grave mistake that landed her in prison, few people would ever describe her as a troublemaker.

So, it wasn’t too surprising when the prison reclassified her to somewhere less secure a year after her arrival.

The culture at her new yard, Santa Cruz, was dramatically different.

At Lumley, she and other women described constant oversight and abuse. N'sangou said that walls and doors shielded corrections officers from being caught on camera dishing out beatings or other harsh treatment.

In the medium security yard, there was more freedom —less commotion when someone wanted to go for a walk, play basketball, or simply stay put and sleep.

The main difference between the two yards, though, was population. Santa Cruz had a lot more people, and suddenly N'sangou felt like a small fish who couldn’t get her old job at the commissary back. That work, she learned, was a coveted position. It required more politics and popularity to be considered. So, being a woman with an advanced education and skills, N'sangou got placed back into teaching.

But there were rumors around the yard about a job that was even more coveted than the position at commissary. That job was upper echelon, and the women who got it were a different kind of prisoner. People called them the “Televerde Girls.” They were the queen bees of the prison: looked up to and also reviled.

Some women recounted their experiences being on the other side of that kind of love and hatred as a kind of social hierarchy within the prison.

“I can remember getting crap from people on the yard, saying, ‘Oh, you know, there's a Televerde girl, stay away from her,'” said Jeanette Hanafi, who worked for the company while incarcerated as well as after being released. “It was just a big deal to work at one of those places.”

During off hours, N'sangou remembered that the Televerde women would band together.

They all looked nice, had their hair pulled back, and were well-spoken. They were also able to leave the prison every day and be in the free world. They worked on million-dollar contracts selling software and other products to big tech companies. They were paid the best in the prison and owned the best things — partially because they could afford them, but people often just gave things to them, like candy, stamps, or cigarettes (the equivalent of cash that could be used to barter for other goods).

But a job at Televerde wasn’t something just given to people. N'sangou would have to prove that she deserved it. Out of hundreds of people in the Santa Cruz unit, only a handful would get the job.

There was a challenge, though: her skin color. Historically, women at Televerde have primarily been white.

Data from the Department of Corrections shows that more than 70% of the women hired at Televerde are white women, with Black women making up only 7% of those hired, despite representing 14% percent of the prison population. Latina women made up only 15% of those hired by the company, even though nearly 40% of the prison population is Latina.

Televerde says there is little it can do about the hiring pool, since the Corrections Department is in charge of advancing candidates for hire. “We have one requirement to work for our company — a high school diploma or GED. ACI and AZ DOC also have a requirement — the women who work for us must be without behavioral infractions for at least six months prior to applying,” said Kellie Walenciak, head of global marketing for Televerde. “The reality is that these requirements do prevent many women — across demographics — from being able to work with us.”

Because prisoners aren’t considered employees of Televerde, they are also not bound by federal equity hiring requirements, and the department only requires that work crews be racially integrated.

“Don’t even try,” one person told N'sangou, she said. “They don’t hire Black girls.”

Still, she persisted. The interview required a typing test, a phone interview, and an exam. And it took grit.

N'sangou compared the lead-up to the interview to mental “hazing.” Being good for the job wasn’t enough. She’d have to grovel, play nice, and work the game of what many prisoners describe as “prison politics.”

She knew that she could persevere. It wasn’t just that she wanted the pay — she needed it. To keep custody of her child, she needed more money. Her daughter needed medical care, items for school, and other things that a young girl simply wanted in her life. But N'sangou couldn’t provide that with a job that paid less than 50 cents an hour.

Once the applications went in, only a few people were interviewed, including N'sangou.

Weeks later, without hearing anything, a piece of paper was thumbtacked to the bulletin board with all of the new hires for Televerde. The women crowded around the board. They grabbed and pointed at the paper. One by one, they walked away from the board, ecstatic or disappointed. When N'sangou saw her name, she was relieved. She felt she could provide what she needed for her daughter.

Within her first few days of starting, she said a manager told her she should feel lucky to have her job.

“Why?” N'sangou asked.

Because, they answered, she didn’t “sound Black.”

‘Divine inspiration’

Almost two decades before Ronald Bell started Televerde, he had done business development at Arcosanti, the famed urban-rural-green habitat in northern Arizona known for selling custom iron bells and tours of its — now — Instagrammable architecture.

Bell only worked a year for Arcosanti and its architect-philosopher, Paolo Soleri. It was a blip — a sabbatical, really — in his 12-year career as a manager at Xerox Computer Services, according to his LinkedIn profile. But it was a pattern in his life toward helping out causes bigger than himself.

By the mid-1990s, Bell had been working two lives: one as a volunteer to get preachers inside prisons to minister to incarcerated people, and another as an internet and software entrepreneur trying to gather large sales for big-name clients in tech.

The business landscape for Bell boomed in the 1990s, when companies were all-in for software that would launch them online. But the market lacked salespeople, and it wasn't a productive use of their time to have them pounding the phones all day making cold calls.

“Those kinds of calls are just brutal for high-paid sales reps that are in the field,” Bell said in an interview with The Republic last year. “Who wants to do that, you know? We called it ‘dialing for dollars.’”

It was around that time that Bell said he had “divine inspiration”: to merge both his passions for tech and helping prisoners. At the Arizona Center for Women in 1995, located at Van Buren and 32nd streets, he worked out a deal with the Department of Corrections and Arizona Correctional Industries to set up a trailer in the yard of the women’s prison, connect landlines to the trailer, and train women at the facility to make high-end cold calls for tech companies and then turn the leads over to salespeople.

“It was an incredible productivity enhancement,” Bell said, adding that there were financial benefits for using prisoners. Televerde only had to pay the minimum wage, which would go directly to ACI — not the prisoners. ACI would then pay the prisoners a fraction of the minimum wage. ACI would also charge an 11% fee for hiring and managing the prisoners. Bell didn’t have to pay rent, and he didn’t have to pay for benefits. And though the job wasn’t considered dangerous, if anyone was ill or got hurt on the job, there would be no recourse for prisoners to get workers’ compensation.

“The employees are at-will employees,” Bell said. “So, it's easy to bring new ones on board, and furlough them if necessary.”

Bell moved on from the company in 2000, after handing over his title as CEO to John Hooker a few years earlier. Since then, Televerde has become one of Arizona Correctional Industries’ largest clients, providing work for more than 200 female prisoners at a time.

One of them, Michelle Cirocco, joined the company just as Bell was leaving.

Like many prisoners, Cirocco came from a modest background. She had been a bartender and worked as a hotel cleaner before being slapped with a fraud charge in the 1990s.

She wanted to find a way to not come back. But there wasn’t anything being done at the prison to help. For years, Cirocco worked in-house prison jobs raking rocks around the prison yard. It was work for work’s sake, she said, and didn’t help with rehabilitating her, as the department claimed its work programs are supposed to do. She and her friends often joked that wherever they worked around the perimeter, corrections officers would follow, messing up the grounds again so they would have something for them to do later.

So when she came across Televerde in 1999, she said she “jumped at the opportunity.”

Michelle Cirocco is chief social responsibility officer for Televerde, an integrated sales and marketing technology organization based in Phoenix.

Photo illustration/Arizona Republic; Photo: Michelle Cirocco

Her first impression was that the women who worked there all had nice things. They looked pulled together. They appeared to be on their way out of prison, and had plans to do something with their lives. Televerde, she said, wasn’t like the other programs inside. It was an opportunity for freedom.

To get in, she had to take a typing test and go through interviews. It was tough, she remembered, but not impossible. And she remembered the feeling of gratitude and being treated like a regular member of an office.

It was her first real job where she could see herself in a career. And, in many respects, it was akin to getting an informal business degree. Hooker, the CEO, would give the women in Cirocco's group a stack of annual reports, and they would be required to write on them. They would have to learn the same language as their competitors.

This treatment of prisoners as people and workers rather than just cheap laborers was the focus of a Harvard Business Review study, which held Televerde up as a model for how other companies could garner internal respect and build a better and healthier work culture.

Many women who joined Televerde said they shared the same experience of being treated as a human — often for the first time — since entering prison. They said they were called their names instead of "inmate" or their corrections number.

“I was productive, learned marketable skills, and it provided a pathway to a career I never dreamed of,” said Valerie Ochoa, a former prisoner who now works for the company. “Many women's lives have changed because of these programs.”

Other prisoners said that even though it wasn’t their ideal job, it wasn’t the worst, and they were thankful that they could do something less labor intensive than other prison jobs.

“Would I say it was a terrible experience? No,” said Gina Girardot, who worked for Televerde while incarcerated in 2017. “When you are inside of prison, these are actually a privilege, because the other jobs only pay 15 to 45 cents an hour working in the kitchen or doing yardwork or other people's laundry. I guess that's the gimmick!”

Cirocco also saw the benefits at Televerde almost immediately, and eventually got hired by the company after her release as a salesperson. Within a decade, she worked her way into her current role as executive director of the Televerde Foundation, a nonprofit attached to the company that provides job placement, housing services, business training, and resume building for women who aren't hired by Televerde.

As a result, the women who take part in Televerde's training — even if they don't work for the company — have only a 5% likelihood of going back to prison within a year of their release, according to a 2020 report that was created by the Seidman Research Institute, a public policy research group at Arizona State University's W.P. Carey School of Business.

The Arizona Republic found similar results, and went further to show that women who worked at Televerde even were more likely to stay out of prison longer than other women in the general population.

However, The Republic found by the fifth year after their release, Televerde workers returned at a similar rate to other women in prison.

Despite the company’s glossy image, there is still intense criticism from some former workers, including longtime employees who had once been fierce loyalists.

A civil lawsuit from 2019 claims Televerde’s related company, Pegasus, retaliated against a prisoner for filing a Fair Labor Standards Act complaint for wage theft, asking for lost wages. That dispute was eventually settled out of court.

One woman said she reported the company because prisoners were forced to work in trailers with no air conditioning in the dead of summer, conditions that risked some women becoming sick from the heat. (Televerde said this was a one-time occurrence and prisoners signed waivers saying they worked in the trailer on their own accord, and were told to leave once the trailer hit 85 degrees.)

Three more women compared Televerde’s training to a mentally abusive ex-boyfriend. One said a Televerde trainer told her that her job would be the best she could ever get because of her felony charge.

But the most consistent criticism from former workers is how the company overworks their prisoners and pays them so little in return.

Still, even with those criticisms, dozens of women have also come forward in defense of the company, saying that criticisms against Televerde are overblown, made up, or that other women who complained were just “weak” or “bad at their jobs.”

A living wage was too expensive

During her first few weeks at Televerde, N'sangou remembers going into the bathroom. She looked above the sink and for the first time in five years, she saw her own face: her light brown skin, large eyes that looked softly at people, and dark hair.

Prisons forbid mirrors — the department says they can be used for weapons. For years, N'sangou would only see outlines of herself every now and then in windows, or she studied herself in the reflection of metal tables that distorted her appearance, like looking at a silhouette through blocked glass.

Now that she worked at Televerde, N'sangou needed to look perfect. It was a condition of her employment: Be a Televerde Girl. She said she was ordered to represent the company at all times, on and off the yard. Speak proper, look proper, be the best person in the prison, and “wear your brightest orange,” N'sangou said she was told.

“Make sure your pants aren't wrinkled and make sure that you curl your hair with contraband hair curlers, because you don't have pearls,” she said. “It's the most ridiculous standard, but it is an actual standard.”

Her first day on the job, N'sangou listened to every word the trainers gave her. They said, she explained, that they were going to spend a lot of money on her, and train her to be a master of technology and software.

It’s what Televerde did best: master the ins and outs of software and technology, and generate leads for companies like SAP, Microsoft, Yahoo or Salesforce. They then turn those leads into multimillion-dollar deals. While some similar companies had call centers in-house, paying staff at least minimum wages and benefits, others were known to outsource their call centers to countries where they could pay sometimes a third of the price for workers, even less than Televerde’s prison workers.

But after a year of working with Televerde, N’sangou was still only making $5.85 an hour.

That rate is far below what someone on the outside would have made for the same job.

Lead generators currently can make between $20 and $40 an hour with commissions and benefits comparable to similar jobs elsewhere, according to salary trends on Indeed. Currently, at Televerde, prisoners who work in a similar job to N’sangou are paid at least the state’s minimum wage of $12.80 per hour, with no benefits.

But the women at Televerde walk away with far less than the state minimum wage. After deductions, women are only allowed 50 cents an hour to spend. The rest goes to various fines and fees, room and board, utilities, and whatever is leftover goes into a retention account that is given to the women once they leave.

Even when they work for a private company, like Televerde, states can exploit their prisoners under the 13th amendment, which barred slavery except in cases of imprisonment.

Companies can use prison labor in Arizona to make or sell products within the state. But they are not required to pay minimum wages, workers compensation or employee taxes. And most don't. Out of the dozens of private businesses that ACI contracts with, Televerde is one of only three that offers prisoners the state minimum wage before the state deducts their fees from prisoners.

Televerde justified its wages with the skillset of the women coming in: Many of them don’t have telemarketing or business skills at first, just a high school degree. “We don’t turn out low-skilled labor,” said Walenciak, the head of global marketing for Televerde. “We turn out consummate business professionals in partnership with the (Department of Corrections). This is why companies hire our graduates and poach our employees.”

Walenciak compared the opportunity to college students working internships and added that their business model — though on the outside could appear to be profit-driven — could easily use offshoring, instead. “We’d have healthy cost savings with that model and far less scrutiny. Instead, we choose to work within this incarcerated model because we know the impact we can have.”

Despite being low compared to her free coworkers, Televerde’s pay was the most money N'sangou ever made while incarcerated. In return, she went back to prison every night with homework, and was expected to come back the next day with knowledge.

She described the work as “fast-paced” and “high pressure.” For N'sangou and the other women she worked with, that manifested itself in long hours, managers who berated her for not working hard enough, or being given dead-end contracts in an effort to see how far they could be pushed to the edge.

Almost daily, N'sangou said, her bosses and managers told her she wasn’t a good enough worker to bring the jobs over the finish line.

She remembered one manager scolding another prisoner, saying: “If you can sell thousands in meth, you can sell this software.”

Fearing she would lose the job, N'sangou said she went back to her cell to study harder every night. And though many succeeded and were natural salespeople, others like N'sangou went back to prison mentally beaten. But she pushed on: She couldn’t afford to lose the hourly wage.

‘I didn’t feel comfortable’

The truth was that N'sangou hated sales. Maybe some people thrived from being broken down as a way to gin up sales, but she was not one of them. Her strength, she said, was management.

But prisoners — according to department rules — can’t "be placed in a supervisory capacity over any other inmate." Televerde, however, seemed to make its own rules. When the prison went on lockdowns, Televerde was able to get some women out of their cells. While the Department of Corrections had strict criteria about formerly incarcerated people not working alongside current prisoners, N'sangou’s bosses were women like her, including Cirocco. And when N'sangou proved to be a strong manager, they moved her to oversee contracts with teams of prisoners and civilians.

And the work got even tougher as Televerde took on the German software giant SAP as a customer.

When that happened, N'sangou said she got saddled with dozens of other clients. While the company focused on SAP, her bosses, she said, gave her the company’s “pearls,” and she should be grateful to have such big names to work with and have on her resume.

Indeed, N'sangou was excited to work in this realm. She had amassed enough knowledge to rival people with MBAs doing the same work, and she could have conversations with people on the outside who were working in detailed technology.

“When I was inside, I was deprived of all kinds of technology,” she said. “Cell phones were not a thing.” She described how excited she was to learn about a new technology called Wi-Fi. She had written to a friend who graduated from Wharton Business School at the University of Pennsylvania about the technology, and her ability to sell it.

Her friend, perplexed about the language N'sangou was using, wrote back: “That’s so funny,” she remembers her friend responding back. “I’m doing the same thing.”

N'sangou was employable beyond even what she was before, but it all came at a dramatic cost to her mental health, she said. And while she was happy with the money she brought in for her daughter and her savings, the work was also physically draining her.

She described working 13-hour days, which pushed her to a tipping point. She remembered one time a project coordinator for clients such as Accenture and Microsoft complaining about only clearing $80,000 in commissions for the year.

N'sangou was lucky if she made anywhere near $12,000, in yearly wages.

But what was most unforgivable for N'sangou was that as she became more experienced in her job, she noticed people being promised work after release but offered lower than average salaries, and continuing to work in prison-like conditions. She said a mentor of hers excitedly told her about being hired by Televerde after her release at $48,000 per year, but was subject to random drug tests by management.

Televerde said that their drug-testing protocol is standard for a company that wants to maintain a drug-free workplace, and that it has staff members undergo drug screens if they think anyone is high or intoxicated.

The company even offered N'sangou $65,000 a year to join after her time inside, but she also would have had to be called up to do a urine analysis at any time, she said.

“Why would I want to work in a space like that?” she asked.

For N'sangou, it felt wrong to leave prison just to go back into it every day, no matter the middle-class salary.

She also noticed people were strung along and promised jobs, but then never got them once released. Televerde boasts that 25% of the incarcerated women who work for the company end up employed at the main headquarters, but for women who don’t, they have the option to get placed with partner companies, such as Trapp Technologies. (Trapp's Chief Revenue Officer Jay Bouche declined to answer questions about the company's relationship with Arizona Correctional Industries, citing a legal contract with the state that bars it from openly speaking with the media about using prison labor.)

But that backup plan didn’t ease N'sangou’s worries.

“I didn’t feel comfortable because I didn't have a future at Televerde that was certain,” she said, describing all of the different people she saw being promised jobs and then leaving empty-handed. “Why would I want to work in this place where I don't know what's gonna happen, especially given the amount of energy and time I put into this work, and I don't know if that’s going to translate into a job when I come home?”

Two years away from her release, and knowing that if she quit she could be disciplined and sent back to scrubbing toilets, N'sangou didn’t want to give her time to a company that didn’t keep its promises.

It wasn’t about the money

N'sangou wrote to her boss, Michelle Cirocco, that she would no longer be working at Televerde and gave two weeks’ notice.

“I just don’t think that this job is a fit for me,” she said she wrote in the letter.

Technically, all of the jobs offered by ACI companies are voluntary. But leaving comes at a cost.

Corrections officers bar people from working similar-paying jobs, and the prisoner handbook says that incarcerated people can get demoted down to working a job that pays less than 50 cents an hour if they refuse to work their assigned jobs. Prisoners also describe being sick or injured, and still being forced to work or face consequences, such as having their phone or visiting privileges revoked.

When N'sangou quit, she already had another job lined up at a warehouse making similar money. It was an unusual circumstance, since most people never get to just transfer to another job when they want, even if they don’t like the work, their pay, have a bad manager, or don’t mesh well with their co-workers, according to the prisoner handbook.

Still, N'sangou managed to talk her way into a new job with her officer.

Many of the other Televerde women tried, she said, to convince her to stay, too. They were proud to have worked for Televerde.

How could N'sangou want to leave? And how could she not see the good that Televerde was offering to her and her fellow prisoners?

But N'sangou was reaffirmed before she left Televerde. SalesStaff, a former competitor of Televerde, poached her while she was a project coordinator inside. They would offer her $110,000 a year — $55,000 more than what she said Televerde offered her for the same job.

One woman who recently left the company — but asked to remain unnamed since she still remains in contact with workers there — said she learned Televerde was hiring people for similar positions as women who were formerly incarcerated, but paying the women who were never incarcerated tens of thousands of dollars more. Televerde denied paying formerly incarcerated women less, saying the company uses an industry-standard pay scale.

But N'sangou’s job offer proved to her that it wasn’t just her uncertain future that was bothersome. She said after the experience with how she had been overworked, and paid so little, that she didn’t want to be in a place that would profit off exploiting people’s hard work.

“Televerde’s advantage in the business world is not unlike that between the North and the South during slave times, and I think that that's really important to know,” N'sangou said. “They are paying nickels on the dollar for every one of their people that work for them, and because of that they're able to get an edge in their industry. They can afford things that their competitors can’t, and I know because I've worked for the competitors who did pay people living wages.”

And despite management’s rhetoric about how they were giving women a chance to make their lives better, three women — including N'sangou — compared the company to an “abusive boyfriend” who used gaslighting tactics to keep women working.

“They make it sound like this is the best you’ll ever do in your life,” a former Televerde worker, who left within the past year, said. “It’s abusive behavior.”

After leaving Televerde, N'sangou said she felt relieved that she wouldn’t have to battle for her dignity anymore, and that she would have happily walked out of that company to mop floors for the rest of her time in prison. (She later worked for Morrison Management Specialists inside the prison managing its warehouse, and since being released, she is the executive director of Mass Liberation Arizona, a social justice nonprofit that works to end mass incarceration in Arizona.)

Like many women, N'sangou said she doesn’t regret her time at Televerde, or any of the jobs she had while incarcerated. But she does resent the people who she worked for. Dozens of women interviewed agreed that Televerde, generally, is a good model, but simply needs to live up to its public-facing motto, which is respect. Paying people fairly and equally, the women have said, would be a good start.

In that vein, it wasn’t that N'sangou didn’t learn anything while at Televerde. It was that her entire time at the company felt like she and her friends were being victimized by a company that claimed to do good, but refused to acknowledge the harm they contributed to.

“This place definitely shaped the trajectory of my life, and I will never be the same,” she said. “I don’t think I’ll ever forgive them for the harm they caused.”

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Arizona’s prison system exploited her labor. She kept her dignity