She was homeless for the first time in her life. How did she climb out?

For the first time in her life, Tonya Hogan was without a home.

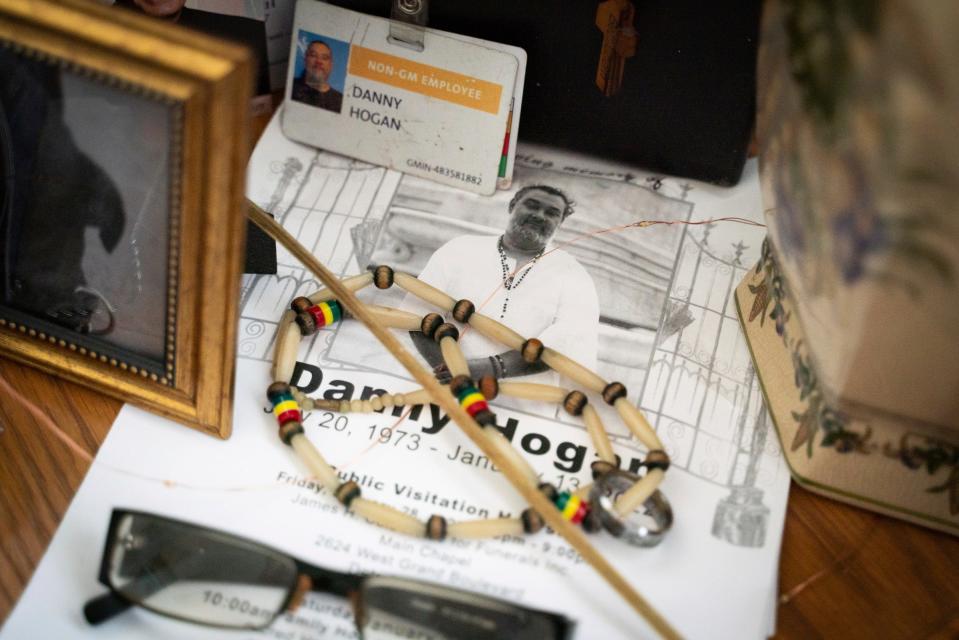

Packed within the four walls of her shelter room — with its speckled floor and fluorescent lights — were glimmers of Hogan’s universe: stuffed animals on a bed, her service dog Pepper, her late husband's work lanyard.

Stacked milk crates held what nightstands usually do. Her winter jacket hung on a locker-size closet. Her broken truck was parked outside. It held food and clothing. Her mattress, furniture and her father and great uncle's military flags and medals sat in storage. She had to leave everything else behind.

It was like this for about a year.

In 2022, Hogan’s husband died from COVID-19 complications. Soon after, Hogan, unable to pay the bills as she grappled with grief and health challenges of her own, lost the home they hoped to own one day through a land contract — a three-bedroom bungalow in Detroit’s Grandmont neighborhood.

“I had never been in a shelter — never thought that I would be in a shelter,” Hogan, 50, said.

Hogan is part of a growing number of women and families in Detroit, Hamtramck and Highland who are homeless. In 2022, the number of women identified as homeless in shelters rose 18%, according to the Homeless Action Network of Detroit (HAND). The number of unhoused families went up 14% during the same period. For these groups, the need for shelter far outweighs the number of beds available.

“What we're seeing in the homeless community is this dynamic where women and children are being displaced at a rate that is really unprecedented,” said Linda Little, president and CEO of the Neighborhood Service Organization (NSO).

Homelessness, housing experts say, is not a monolith. It has multiple root causes, from mental health challenges and substance abuse to evictions and affordability hurdles.

It’s a family living out of a car. It’s a person sleeping in a vacant home. It’s a teenager couch surfing. These groups are likely uncounted. That means available data — which primarily tallies the unhoused in shelters and housing programs — doesn’t paint a true portrait of the scale of homelessness across the city.

Once people do find shelter space, the path out of homelessness can be arduous, with long wait times for housing choice vouchers and housing leads that turn out to be dead ends because of the shortage of affordable units and landlords willing to accept subsidies. Then comes the struggle to maintain stability once a person does have a roof over their head.

“When life happens and you have a series of events that causes you to have housing instability, the root cause of that is truly poverty,” Little said. “When you don’t have emergency funds and the bandwidth to withstand multiple life crises, it's easy to find yourself in an unstable housing situation.”

That’s what happened to Hogan. The Free Press and BridgeDetroit followed her from a shelter to a home. Here is how her journey started.

Falling into homelessness

Tonya and Danny Hogan had plans to travel the country. It would be a belated honeymoon trip — to California, Las Vegas, Alabama and Georgia — visiting family and scoping out a new place to live. They did everything together from fishing in the summertime to picnics downtown by the Detroit River.

“We just really enjoyed life together,” she said.

Tonya and Danny were high school acquaintances who reconnected later in life. Their worlds were intertwined. Both grew up near one another on the west side of Detroit. When they met again, they were both divorced. They had each lost their mothers. They communicated through Facebook Messenger for almost a year before they started dating in 2015. She told him she wasn’t looking for any games and wanted someone to grow old with and he agreed.

Tonya married Danny, her best friend, in September 2021. Four months later, he died.

One January day, Danny woke up and couldn’t move, talk or breathe. After he was rushed to Sinai Grace Hospital, doctors put him on emergency dialysis. As his body battled COVID-19, his lungs collapsed. His heart stopped and started, stopped and started again. Then it gave out.

Danny died on Jan. 13, 2022 — 18 years to the day that Tonya’s mother passed.

The next time she would see him would be two weeks later at his funeral. Tonya, who also tested positive for COVID-19, grieved in isolation.

Before he died, Danny was in the process of purchasing their rental home through a land contract deal, Tonya said. They put a lot of work into the home, building a vegetable garden and handmade trails. Pepper would run around in the backyard.

Tonya — who wasn’t working when Danny died — was unable to afford the home and had to give it up.

“I literally was planning a funeral and packing at the same time,” she said.

It was a dark time as she grieved. She stayed in bed and declined phone calls. But her home was no longer her own and so Tonya and Pepper left in April.

For three days, they stayed in her truck and then with a cousin for a brief stint while a roommate was away for a couple days. Tonya called shelters. It took six days to find placement in a room. She eventually ended up at a Salvation Army shelter for women and children in April — three months after Danny’s death.

That first week, all she did was sleep. She was hurting, tired, depressed and suicidal. She landed a couple jobs but had to quit because she struggled to find a place to leave Pepper while she worked.

When Danny died, Tonya didn’t have any savings to fall back on. The pair put their money into fixing up the kitchen, bathroom and garage in their home and investing in Danny’s plumbing business, she said.

Over the years, she worked part-time retail and caregiver jobs and other odd gigs. Tonya received disability benefits up until 2015 because of back pain and kidney problems from end-stage renal disease. She has had a kidney transplant.

After Tonya and Danny got together, he primarily supported the both of them financially. And so when he died, she lost everything.

Shelters are overwhelmed

The Salvation Army Booth Services shelter has 55 spots, but has had as many as 80 clients in its regular beds and overflow room so the shelter wouldn’t have to turn people away.

The 56 shelter beds at the Neighborhood Service Organization’s new emergency shelter for women are all occupied. The shelter, which opened in April, is consistently full.

It’s the same story at the Detroit Rescue Mission Ministries (DRMM) where 410 beds for men, women and children are also taken.

“We've been overwhelmed with the number of people who've been calling us that they need to go to shelters — especially women and children,” Chad Audi, president and CEO of DRMM, said in May.

Shelter leaders attribute the growing number of women and families seeking emergency beds to economic conditions and system lags. Many of the challenges are centered on housing, including a shortage of affordable units and a long waitlist for limited housing choice vouchers. They also point to the end of pandemic-era eviction moratoriums, recent employment losses and insufficient savings to cushion emergencies.

“You add all of those things together and you get this conundrum that we see,” Little, of NSO, said.

Many Detroit families could not withstand a $400 emergency, a report from Detroit City Council's Legislative Policy Division noted last year. About 32% of Detroiters are living in poverty.

Sixty-five percent of Detroit households can't afford to keep up with the basics, including rent, child care, food, health care and utilities, according to the United Way.

“Any one thing can lead to a displacement,” said David Bowser, associate director of Detroit’s Housing and Revitalization Department. "A past-due medical bill, a couple past-due rent payments can lead directly to homelessness because people do not have the savings and the economic mobility to … get past those incidents.”

People in Michigan — and metro Detroit — earning minimum wage ($10.10) would have to work two full-time jobs to afford a two-bedroom rental costing $1,126, according to recent figures from the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

At the same time, housing costs have gone up. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Little said NSO would find rental units for clients for $600 to $750. Now the landlords the nonprofit contracted with for decades have doubled the rent, she said.

“We have housing unit stagnation,” she said. “We don't have enough units. Even though we have a lot of builds that are going up, it's just not fast enough and at the price point that most Detroiters that have been here can afford.”

Bowser agreed that there is a shortage of affordable housing.

“Quality, affordability and availability are almost pretty rare to find and I think that that's why we need navigators and we need landlords who are on board and compliant,” he said.

Bowser said that while Detroit has fewer homeless encampments compared with other cities, the unhoused population looks different in that people may be living in uninhabitable structures.

He pointed to city programs that can help, including Code Blue — where city staffers connect people dealing with a housing emergency with hotel stays and case managers. A new Detroit Housing Services office, backed by $20 million in pandemic relief dollars, launched in June to link Detroiters to services, including collecting vital documents and finding homes. It’s available through a new hotline — the Detroit Housing Resource HelpLine (866-313-2520).

The city’s housing and revitalization department distributed $5.3 million in grants for homeless services in 2022. Meanwhile, shelters are overwhelmed.

Here’s what homelessness in Detroit, Hamtramck and Highland Park looks like by the numbers, according to HAND:

In 2022, there were 4,804 people in shelters — up 11% from the year before.

A one-night count of the homeless population in January 2022 identified 223 single women, up 31% compared with January 2021. The count identified 175 families in 2022 — a 133% increase compared with 2021.

In 2021, 77% of those in emergency shelter exited by the end of the year versus 84% in 2020, likely because of the difficulties of finding affordable housing.

How long people stay in shelters has also been ticking up year over year, going from 71 days on average in 2018 to 111 last year.

These are the known figures. There’s also the population that lives in the “shadows,” Little said.

“There's a lot of families living in abandoned homes. There's children going to school every day, from sleeping on a church stoop or in a car. So, we can't count homelessness as just what's in the emergency shelters because there's so many people living in other places who are homeless,” she said.

Homeless shelters and service providers are having conversations about providing parking lots to accommodate families living out of their cars, she said.

The face of homelessness has changed, said Tasha Gray, executive director of HAND. But shelter space has not kept up. Single women and families, she said, typically have fewer shelter spots than single men.

Audi, of Detroit Rescue Mission Ministries, says his organization is struggling to accommodate larger families who want to stay together in one place.

“We're managing but we are overwhelmed,” he said.

Finally, a voucher, but then rejection after rejection

Last April, when Hogan entered the shelter, she applied for a housing choice voucher — a federal program meant to lift families out of poverty and homelessness by subsidizing portions of their rent.

But it’s a difficult program to use.

After applying, the average wait to receive a housing voucher, commonly known as Section 8, in Michigan is about two years. Only a fraction of eligible families across the country get a housing voucher. Meanwhile, thousands of Michiganders languish on waiting lists hoping to be among the fortunate chosen to receive the subsidy when vouchers become available.

Hogan waited more than half a year on the waiting list for a voucher, then spent another four months looking for an apartment that checked all the boxes: accepts vouchers for rent and utilities, allows animals and is in good enough condition that it would pass Section 8 inspections.

After Hogan received her voucher in December, she looked at nearly 30 properties, she said. About half of them rejected her because they didn’t allow pets, didn’t accept Section 8 or her voucher wasn’t enough to cover rent and utilities. Others didn’t call her back or they were already rented out.

She carried a purple spiral notebook filled with notes on places she had visited and programs she’d called.

Nicole Cloyd, a case manager with the nonprofit Community and Home Supports, visited an apartment building in Detroit with Hogan in January. She advocates for clients looking for housing with their vouchers and helps weave through the complicated process.

“I always try to encourage them not to jump on the first thing — weigh your options. Have a plan A, plan B, plan C. So if something happens and you're not approved for whatever reason ... you have a backup plan to fall on,” Cloyd said.

But disappointment is a part of the voucher process.

In February, Hogan toured a one-bedroom apartment in Dearborn where Pepper could roam freely. After the viewing, she was optimistic. But she didn’t end up getting the apartment. Her subsidy was extended a couple times and she kept looking at places.

“People think that once you receive your voucher, then that's it and really it's not,” Hogan said. “You still have to maintain (it), you still have to have inspections. You still have to find work. You still have to try and get yourself where you're capable of weaning off and getting your life back.”

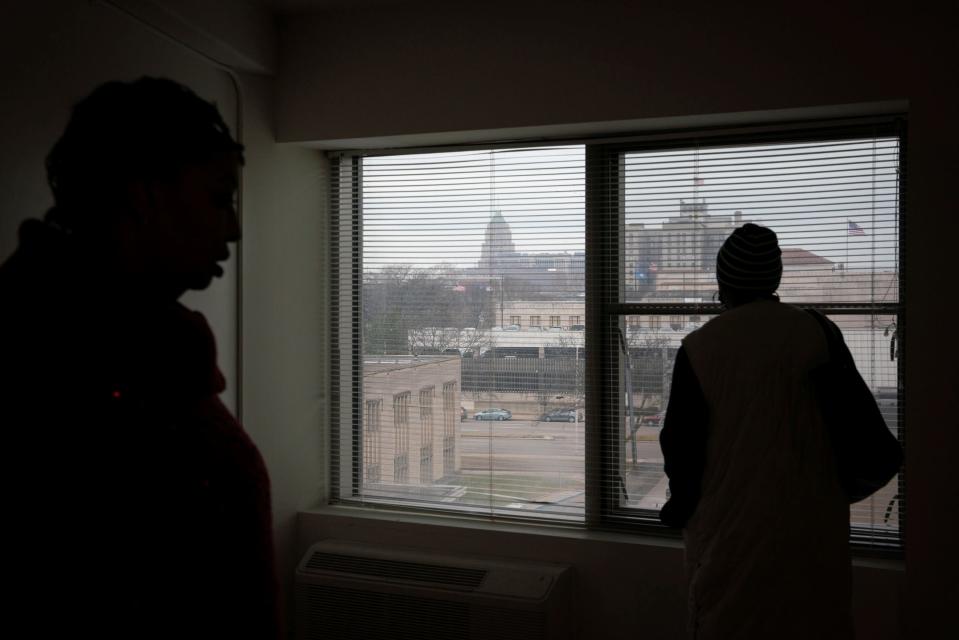

As she searched, she was still at the shelter. At a Bible study in March, Hogan sat surrounded by other women in the shelter.

“Why do we rejoice in the midst of everyday life or in spite of deep heartache? What reason do we have for joy?”

For Hogan, the other women at the shelter were like family. Residents would come up and pet Pepper. She was a familiar presence. They would play bingo together. The women would pitch in to buy cookies and chips. Hogan even made some money in the shelter by doing hair — charging $10 or $15 for different styles.

“We all try to uplift each other, no matter where we're coming from,” she said.

Hogan has struggled with anxiety since she was a child. Though she enjoys spending time with the women of the shelter, life there only heightened Hogan’s mental and physical health challenges. Being unhoused made her feel forgotten, washed and wiped away, she said. That was compounded by aches and pains from her kidney transplant medication.

“It's almost like it was a blessing for me to be where I'm at,” Hogan said. She needed the space to cope with Danny’s death. Her mind and spirit were restless. “But being here I've learned peace, I've learned patience — a lot of patience.”

Gray, of HAND, said mental health challenges are a pressing concern for those who are unstably housed.

“The trauma from homelessness causes some mental health issues,” she said.

The Bible studies were a reprieve as Hogan weathered the highs and lows of looking for an apartment with her housing choice voucher. Pepper, Hogan’s steady companion of eight years, was in tune with Hogan's feelings. Whenever Hogan had anxiety attacks, Pepper was right there, nudging Hogan, letting her know she was not alone.

“It's challenging once you get into homelessness to kind of escape homelessness without some sort of help,” Gray said.

Usually, the first engagement is with the Coordinated Assessment Model (CAM) — a one-stop-shop hotline — and then people are either referred to a shelter or diverted to another safe place to stay. The CAM system itself has received sharp criticism from users about the wait time and referral process. The pathway out of a shelter isn’t quick either, Gray said.

After she lost her housing, Hogan learned of resources she otherwise wouldn’t have known about, such as Gleaners Community Food Bank of Southeastern Michigan’s food distribution, the CAM hotline and Crossroads of Michigan.

It’s at Crossroads, a Detroit-based social services organization, where Hogan — nearly a year into being homeless — picked up free hygiene products and clothing on a rainy February day. Hogan took the bus to get there. She would go to Crossroads at least once a month to get personal supplies and tried to take items back to women at the shelter.

“It’s a hidden gem. A lot of people do not know about us,” said Frank Wilson, a counseling supervisor with Crossroad, who helped Hogan that day.

Crossroads, which has been around for 50 years, helps people obtain birth certificates and IDs to get into housing programs. They have pantries for clothing, hygiene products and emergency foods. They help people get jobs.

Hogan said a lot of women come into the shelter with no shoes, clothes and diapers for their children. She would tell them about Crossroads. People find out about the organization primarily through word of mouth, Wilson said. That’s how Hogan learned about it, too, and received help getting a new driver's license and paying off a DTE bill.

From Crossroads, Hogan walked to Duffield Library, where she borrowed a WiFi hotspot. Otherwise, she wouldn't have access to the internet in her room to look for apartments. While the shelter did have a computer room for internet access, Hogan knew she needed to be looking constantly.

The ice and snow melted that day and fell off trees like rain. With her bag of clothing from Crossroads in a plastic garbage bag, Tonya waited for her bus to the Salvation Army. There was no shelter at the stop where she stood.

Goodbye to room 810

After a year, Hogan was ready to leave room 810. Her boxes sat at the entrance of the building, along with plastic bags filled with her belongings.

“I didn’t even look back,” Hogan said, as she sat in the shelter’s lobby, waiting for the moving van to arrive. Pepper was at her feet.

She was ready to move. This time, to a home. One she chose. One she could make her own.

Residents visited to say goodbye to Pepper, Hogan said. She was excited, yet exhausted. She would miss the ladies, but was relieved she made it.

“It's been an emotional roller coaster, the whole journey here … starting with the lows and then I'll get into a good spirit and then I kind of fall back down, then get back up. So today is bittersweet,” she said in May.

The day started off drizzly and brisk. Hogan left the shelter in a blur.

And soon enough, she opened the doors to her new place near the train tracks — a modest one-bedroom apartment in Melvindale with new carpet and cream walls and a rainbow “congrats” balloon tied to a closet, greeting her. The branches of a large tree shaded Hogan’s corner of the two-story complex. Wind chimes tolled gently.

There’s plenty of space for Pepper to take a walk in this neighborhood. She’s responsible for $50 a month in rent. The voucher covers the rest.

Hogan got right to work, putting Pepper’s food in the kitchen and filling up her water bowl. Meanwhile, Pepper was distracted by the sounds of the neighbors up above — the sloshing of water and stomping of feet.

Hogan started putting hangers in a closet. She still needed to bring in furniture. Her broken truck, at the shelter, has more of her belongings inside and there was stuff inside a storage unit, too. Though she let go of much of her things when she became homeless, Hogan was able to keep furniture upholstered by her aunt, which she planned to bring into her new home.

Hogan sat on top of a storage bin, laughing. She realized she left her medicine back at the shelter, inside her truck, and she’d need to go back.

“Little by little,” Hogan said.

A freight train rumbled outside. A school bus turned a corner. And the sun — it finally came out.

A roof is not enough

Homelessness means existing in survival mode and once a person gets out, that transition is difficult, said Audi, with the Detroit Rescue Mission Ministries.

Having a home is important, but so, too, is being able to maintain it. That’s where supportive services to find jobs, balance a household budget and address substance abuse come in to help people maintain economic stability, housing experts said.

It’s been a few months since Hogan left the shelter. She feels stuck. She needs to find work and generate an income, but is struggling to get her footing.

By August, Hogan applied for five jobs and heard back from one. Her truck is fixed but sits in a repair shop. She can’t afford the $950 to pay for the repairs. She needs a vehicle to get to and from work once she lands a job. Otherwise, she’d need to find employment within walking distance, but there aren’t many options. It’s physically difficult for her to walk to the nearest bus stop. With no income coming in, she has fallen behind on her subsidized rent payments.

For about three months, Hogan slept on her living room floor because some of her belongings, including her mattress, sat in a storage unit as she scrambled to find help to move it all to her new place. Sleeping on the floor flared up her back pain.

She’s in physical therapy to alleviate the pain from a bulging disc pushing against her spinal cord, leading to weakness in her knees. She also has early signs of osteoarthritis. But Hogan said she’s willing to push past the pain because she needs a job.

That’s because she has more financial responsibility now, she said. She feels like she’s falling more and more behind than before she moved in. She doesn’t know how she will climb out.

“I just feel like I'm in a wind tunnel,” she said in July.

At the same time, Hogan continues to struggle with her mental health and she misses Danny. On a ledge near her apartment window, Hogan has set up a makeshift memorial for Danny, with his work lanyard and a little plumber doll. He had a plumbing and heating business.

“I have a place I can call home,” she said. “But being by myself, I still find myself grieving. I find it hard to cook for one.”

Contact Nushrat: nrahman@freepress.com; 313-348-7558. Follow her on Twitter: @NushratR. Sign up for Bridge Detroit's newsletter. Become a Free Press subscriber.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: From shelter to home — how one woman climbed out of homelessness