‘She looks like a baby’: Why do kids as young as 5 or 6 still get arrested at schools?

No one knows how many young children are arrested each year in schools, but a USA TODAY analysis identified an average of 130 a year. We got to know three:

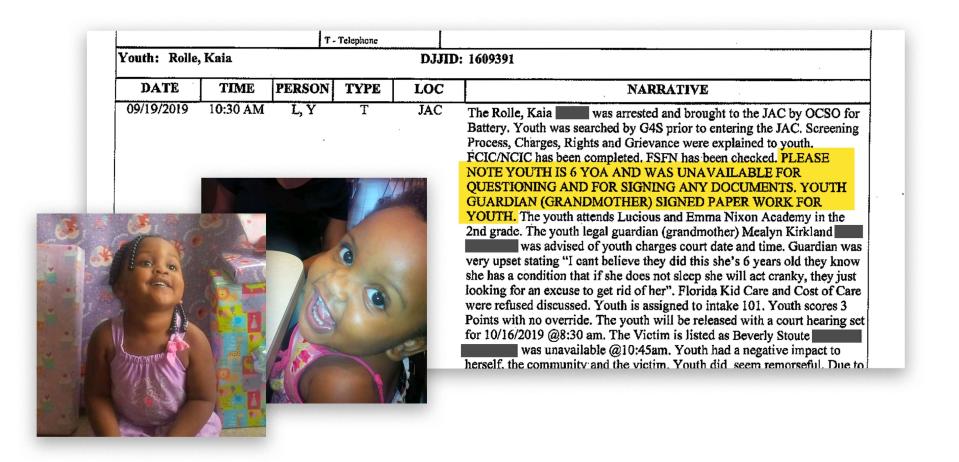

• A 6-year-old, forced from her school in zip ties and charged with battery, even though she was too small for a police mug shot and had to stand on a stool.

• A 7-year-old handcuffed following a shoving match with a classmate over a Sonic the Hedgehog drawing.

• An 8-year-old pinned to a chair and arrested following a tantrum because she wanted to go to a class party dressed in the cow hoodie her mother made for her.

ORLANDO, Florida — The preschoolers filed offstage in royal blue caps and gowns, hugging their parents and ready for treats to celebrate their 2018 graduation from Trinity Learning Academy. All but one.

A 5-year-old took center stage, dancing to upbeat music, legs kicking in white tights and shiny white shoes.

“When Jesus says yes, nobody can say no,” she sang as her aunt recorded the moment. “When Jesus says …”

Her dark eyes shone. Her black curls bounced. This was Kaia Rolle. A diva who hugged strangers.

Barely a year later, the world would meet Kaia as a wailing first grader, forced from her school in zip ties by two Orlando police officers and charged with battery. Police body cam footage captured her cries – “Don’t put handcuffs on! Help me! Help me!” – and stirred outrage around the world, bolstering calls to remove cops from schools and impose a minimum age children can be arrested in Florida.

Now, dancing Kaia lives only on her aunt’s cellphone. In her place is an 8-year-old with extreme post-traumatic stress disorder, separation anxiety, oppositional defiance disorder and phobias of simple things like bugs. She rarely smiles. Strangers get a wary look. Police officers terrify her.

“We know she’s in there,” said her grandmother Meralyn Kirkland. “We just don’t know how to bring her out.”

It seems inconceivable: Educators calling police on elementary school kids for typical child behavior. Temper tantrums. Fighting with other students. Stealing spare change and crayons.

Sometimes they’re arrested. Sometimes they’re not. No one knows exactly how many young children are arrested each year in school. Incomplete federal databases, differing definitions of “arrest” by states, and national records that mix multiple types of law enforcement action against kids make it impossible to parse an accurate count.

But a USA TODAY analysis of federal crime reports identified more than 2,600 arrests in schools involving kids ages 5 to 9 between 2000 and 2019. That’s an average of 130 children a year and surely a vast undercount. The newspaper culled 28 million arrest records from more than 8,000 law enforcement agencies that participated in the FBI’s National Incident-Based Reporting System over two decades. Reporters talked to dozens of criminologists, psychologists and attorneys to interpret the results.

Among agencies consistently contributing data to the FBI, arrests dropped from about 171 a year in 2000-2009 to 94 a year in the following decade. The decline may have been driven in part by the growing body of research that shows harsh punishments can do more harm than good and are often applied unfairly to Black children and those with disabilities.

Even so, cases like Kaia’s continue to pop up as schools turn to law enforcement officers to deal with discipline issues.

No one has studied what life looks like in the years after very young children are arrested, experts say. Because of the nature of trauma, it can be hard to say how one incident plays out over the course of a life.

USA TODAY spent time getting to know Kaia and two others who faced police action in school as young children. What was clear was that their experiences left an indelible imprint on their lives.

Kaia’s grandmother said she is watching her grandbaby die “bit by bit, day after day.”

Malachi Pryor, who was 7 when he was handcuffed and dragged across a hallway in his Denver school after a shoving match with another child, went to therapy because he was convinced he was a bad kid.

Evelyn Towry, who was pinned in a chair and arrested at age 8 in Idaho after hitting her teacher, was scared to go back to school, became terrified of police officers and clung to her mother in public.

The incidents that trigger such arrests are often minor.

Evelyn wanted to wear a cow hoodie. Malachi’s classmate mocked a drawing of Sonic the Hedgehog.

And Kaia? Kaia wanted to wear sunglasses.

‘She looks like a baby’

When Kaia was born, she nearly died. Her skin turned blue. Doctors lost her heartbeat. The emergency team went to work and Kirkland began to pray.

God, if you let my grandbaby live, I will raise her in your faith and always be there for her.

Within seconds, Kaia let out a squeak like a mewling kitten. Then she took a big breath and wailed.

Kaia’s problems at school started in kindergarten. By then, she had developed severe sleep apnea due to enlarged tonsils and adenoids. She woke up frequently. Sometimes she stopped breathing. She slept two or three hours a night.

During the day, she fell asleep while drawing, watching television or riding in the car.

“She’d be talking and she’d go totally quiet,” Kirkland said. “You’d be waiting for the next sentence and look in the rearview mirror and she’d be snoring.”

In school, the sleep deprivation took its toll. She’d throw tantrums, kicking and crying. Kaia’s teachers learned to let it play out until she calmed down.

That didn’t work on Sept. 19, 2019, when Kaia was a first grader at Lucious & Emma Nixon Academy, a charter school in west Orlando. Following a bad night, she’d come to school bleary-eyed and cranky.

Early that morning, her teacher told Kaia she could not wear her sunglasses in class and took them away. Kaia started screaming, kicking and hitting staffers, including school employee Beverly Stoute. Kaia tried to run away when a teacher’s aide led Kaia to an office. Staffers blocked the doors.

School resource officer Dennis Turner witnessed some of Kaia’s outburst, according to police documents. But by the time he moved to arrest her, Kaia was calm. Video from Turner’s body camera shows Kaia quietly sitting in an office with a staffer.

Orlando police officer Sergio Ramos arrived to take Kaia to the Juvenile Assessment Center. He brought zip ties because handcuffs were too big.

But once Ramos saw the little girl, he called his sergeant and objected.

“Sarge, this girl is tiny,” he told his boss. “She looks like a baby.”

Turner insisted the arrest continue. On the body cam footage, one staffer seems to be wiping away tears.

“The restraints, are they necessary?” another staffer asks.

“Yes,” Turner answers. “And if she was bigger, she'd have been wearing regular handcuffs.”

In his arrest affidavit Turner wrote: “Victim Beverly H. Stoute stated both verbally (and) in a sworn written statement that Def. Rolle kicked her on the legs several times and punched her several times on both arms without permission. Stoute further stated she wanted to press charges and would testify in court.”

The defendant stood 3 feet, 10 inches.

The body cam video shows Kaia, wearing a red shirt and a red barrette on her braids, warily eyeing the zip ties being held off camera.

“What are those for?” she asked.

“It’s for you,” one of the officers answered.

Ramos turned Kaia around and secured the girl’s hands behind her back. Kaia began to wail.

The officers led her out of the school, passing blue slides on the playground as they approached the black and white SUV.

“I don’t want to go in the police car,” Kaia cried.

“You don’t want to?” Ramos said.

“No, please.”

“You have to.”

“No, please,” Kaia begged. “Give me a second chance.”

Kaia was taken to the nearby Juvenile Assessment Center, where officials took her fingerprints and tried to take her mugshot. But Kaia was too short to fit into the frame. So officials got a stool, snapped her photo and ultimately released her to her horrified grandmother. Uniformed officials at the center warned Kaia that if she didn’t appear for a scheduled court hearing, she would be arrested, Kirkland said.

“She didn’t know what a court hearing was,” she said.

Experts don’t dispute that there may be cases in which police involvement is necessary. Sometimes young kids come to school with knives or guns.

But police and schools need to think about why they’re arresting kids before they do it, said Tracie Keesee, senior vice president of Justice Initiatives at the Center for Policing Equity. Is the goal punishment? Public safety? Retribution?

“What are we trying to solve?” she said.

An internal affairs investigation into Kaia's arrest by the Orlando Police Department provided Turner's explanation for arresting the child.

“It’s extreme,” Turner said of Kaia’s behavior in a call to a sergeant before the arrest. “I don’t want to do this. I have to.”

“You know, you can always file or do something else,” the sergeant suggested.

“Trust me, I don’t want to do this, I have to,” Turner answered.

The investigation gave no explanation as to why Turner felt he had to arrest Kaia, but it was clearly not something he was loath to do. Later that same day, Turner arrested another 6-year-old student at the same school for kicking his teacher. However, police supervisors stopped the arrest before it went through the full process.

Arresting young children does nothing to change their behavior, experts say. Their brains are so undeveloped that most don’t understand the concept of criminal intent.

At 5 years old, children are just recognizing most letters of the alphabet. At 6, Kaia’s age when she was arrested, children still fear monsters. At 7, they have difficulty with basic spelling. At 8, they are still losing baby teeth.

It may even be unconstitutional to arrest children too young to understand what’s happening to them, said William Lassiter, the deputy secretary for juvenile justice in North Carolina.

“It just makes no sense to involve law enforcement in a case against a 6- or 7-year-old,” Lassiter told USA TODAY. “The fundamental belief of our constitutional system is that if you’re standing trial, you need to understand what your rights are and how to participate in your defense. There’s just no way that a 6- or 7-year-old can do that.”

When children act out, there’s something else going on. Maybe they’re being affected by family problems, medical troubles, disabilities, abuse or violence. In Kaia’s case, her family says, it was her sleep disorder.

The charges against Kaia were dropped, but her story blew up in the media.

Nixon Academy officials did not respond to multiple calls and emails from USA TODAY requesting information about the incident. At the time of the arrest, the school released a statement saying they never wanted to press charges, contrary to Turner’s report. Stoute said the same thing to police internal affairs investigators who scrutinized the case.

"No I did not," Stoute said, according to police documents. "I did not verbally say, 'Hey, Reserve Officer Turner, I want to charge this little person with battery.' No I did not."

Turner, who could not be reached for comment, was fired for not following protocol. Ramos was cleared of wrongdoing.

But Kaia and her grandmother weren’t finished fighting. Kirkland knew all about the school-to-prison pipeline, a national trend in which students of color are disproportionately arrested and sentenced to prison. It rattled her.

An analysis of federal data by USA TODAY showed that of the 5- to 9-year-olds arrested between 2000 and 2019, Black children comprised 41%, even though they make up only 15% of kids that age. That discrepancy among young children is even greater than the rate at which Black teens face police action at high schools.

The reasons Black youth are criminalized so young has been vastly studied, and the explanations vary: implicit bias, failure to recognize trauma in Black children, a tendency to view them as older than they are, a failure to identify learning disabilities and mental health problems.

Kirkland knew she couldn’t change everything. But the arrests of kids like Kaia?

It has to stop, Kirkland told herself. I have to help.

‘Mommy, what are batteries?’

Ten years before Kaia was arrested, Evelyn Towry, now 21, faced her own criminal charges.

Back then, school was a war zone for Evelyn, who has a form of high-functioning autism called Asperger's syndrome. While attending elementary school in the late 2000s, the sounds of other children chewing, students shifting in their seats, paper shuffling, fans whirring – all of it assaulted her senses. She loved dogs and cats and cows and liked to dress in animal costumes her mother made for her because she thought animals were treated better than people.

In her kindergarten class at Kootenai Elementary School in Kootenai, Idaho, she screamed and cried. She tore up papers and refused to listen to teachers. She struggled to recognize emotions. She felt bullied by her classmates.

Before first grade, Evelyn had been suspended numerous times.

Many children with disabilities have similar stories. Some have learning disabilities or emotional problems. Some have poor social skills. Others fail to pick up on cues that a teacher is angry or struggle to relate to their fellow students. Evelyn had so much trouble recognizing emotions that her therapist taped pictures of teddy bears with explicitly named expressions on the child’s shirt to help her learn. Her teachers made her take them off, deeming them distracting, Evelyn said.

Give those types of challenges to under-trained teachers, add in easy access to school resource officers who don’t know each child’s educational plan, mix in frustration, confusion and tension on all sides, and the concoction can be explosive. It happens a lot, said Joe Ryan, a professor of special education at Clemson University.

“It’s very depressing when this happens again and again and again,” Ryan said.

An analysis of federal data last year by the nonprofit Center for Public Integrity, in partnership with USA TODAY, showed that the rate at which students with disabilities were referred to law enforcement was disproportionately high in every state.

Evelyn’s teachers tried to work with her, according to a lawsuit her family later settled with the school district. They gave her snacks. They worked with her one-on-one at times and played soft guitar music. Good behavior earned her free time or popcorn.

On Jan. 9, 2009, Evelyn arrived at school excited about a class partyEven though she wasn’t supposed to wear it to school, . Evelyn, then 8 and in third grade, arrived in a cow hoodie her mother had decorated with black spots, ears, a tail and a peach glove for the udders. The school had previously banned Evelyn from wearing animal outfits, saying they were too distracting.

The day of the party, Evelyn’s teacher told her she couldn’t partake in the festivities unless she tucked in the tail and ears of her hoodie, according to court documents. Evelyn says she complied, but her teacher still refused to let her go to the party. Evelyn eventually bolted and ran toward the portable classroom where the celebration was underway. Her teacher called staffers and told them to stop Evelyn at the door.

Soon Evelyn was screaming, crying and clinging to a nearby railing. Two teacher’s aides pried her hands loose and carried the 54-pound child back to class.

“Anytime you go hands-on with children with autism or on the spectrum, it’s going to escalate quickly,” said Lauren Gardner, administrative director of the autism program at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in Florida. “We have to be able to take a step back, take a deep breath and say, ‘What is the real issue now?’ and, ‘What are we willing to go to battle over?’”

Evelyn was forced into a chair by staffers. She kicked, yelled, spit and hit. She pinched her teacher’s breast, hard. On it went, until the principal called the police.

Evelyn was in fight-or-flight mode, the clinic director of a children’s mental health center told the court during the Towry family's lawsuit. Asperger’s children believe that these kinds of scenarios are life-and-death situations.

“When this child left the room, she was carried back by two teachers, and it was already too late,” he wrote in his report.

After about 30 minutes, Evelyn began to calm down.

It didn’t matter. In the police report, the sheriff’s deputy wrote that Evelyn’s teacher and principal “wanted to have charges pressed because they they felt they are not getting their point across to Evelyn or Evelyn’s parents.”

Policies on calling police vary from school to school or even child to child. Some teachers feel arresting children is the wrong call. But other educators, be it due to frustration, safety concerns or an easy access to law enforcement in schools, call on cops to intervene.

In Layton, Utah, a principal called police to report that a group of second graders had stolen items including $25 in change, a Rubik’s cube, a stapler and crayons.

In Boise, Idaho, a principal demanded police file charges against an elementary school child who broke a school window with a rock.

In Memphis, Tennessee, an elementary school boy was charged with simple assault for scratching another child on the nose.

The deputies told Evelyn she was being arrested because of the batteries that had occurred. As they led her to a patrol car with handcuffs locked around her wrists, Evelyn saw her mother in the parking lot.

“Mommy, mommy,” she cried through sudden tears. “What are batteries? What are batteries?”

The charges were quickly dropped. Evelyn transferred to another school and improved, she said, because the teachers better understood how to work with her.

And, according to court documents in the Towry lawsuit, at least one teacher at Kootenai Elementary was happy to see Evelyn go. On her Jan. 9, 2009, planner, the teacher wrote "handcuffs - Last Day ET. Phew!" The entry was followed by a smiley face symbol.

More than a decade later, Evelyn doesn’t think her arrest caused post-traumatic stress disorder or lasting mental health problems.

Today, she works part-time bussing tables at a restaurant. She supplements that with Social Security, rents her own apartment, has a boyfriend, maintains a close relationship with her mother and dotes on her 13-year-old cat, Hazel. She hopes someday to do voice-over work for animated television and film.

While upsetting, not every arrest of a child is clinically traumatizing, said Steven Marans, co-director of the Yale Center for Traumatic Stress and Recovery. So much depends on the child’s life experiences before the incident, the way the arrest is conducted and the support they receive afterward.

Evelyn is still angry about what happened. She hated police officers for a long time and, while that fury has faded, she still panics when she sees them.

“Just because someone has a disability doesn't mean they don’t have the ability to understand things,” she said.

Evelyn is appalled that schools are still arresting young school children. Since her arrest 13 years ago, USA TODAY documented 1,061 arrests of children ages 5 to 9 at elementary schools across the country, and, again, that number is surely an undercount.

“I feel quite alarmed and disgusted by how kids are being arrested,” Evelyn said. “It doesn't matter what they do, they are children.”

‘Right-wrong family’ pushes back

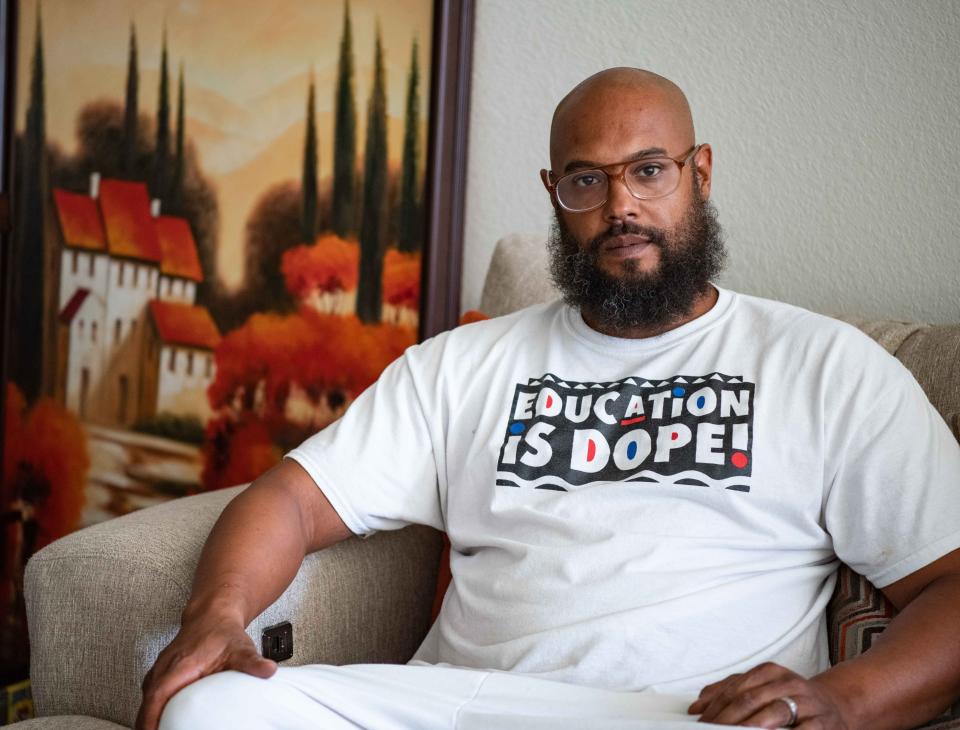

Brandon Pryor paced in front of Florida Pitt Waller school in Denver, angry, anxious and blasting out his disbelief on Facebook Live.

It was April 19, 2019. A school staffer had called Pryor to say his 7-year-old son, Malachi, had been handcuffed after “an altercation” with another second grader. But when Pryor arrived, the school wouldn’t let him see his son. At least four police officers stood behind the purple front door to make sure Pryor didn’t get in.

And Pryor was seething.

“This is egregious,” he said on the Facebook video, which has been viewed 30,000 times. “This is completely unacceptable, and I am pissed off right now.”

Pryor knew he had to stay calm. The Black, 6-foot, 2-inch former linebacker for the Oklahoma Sooners knew losing his cool in front of the cops could land him behind bars — or worse. So he didn’t shout. He firmly spoke his piece into the camera.

“I’m trying to keep it together you guys, because I’m no good to anybody locked up and in jail,” he said.

He also accused the school of discriminating against young children of color.

“You all are criminalizing our kids inside these schools and then you want to lock me out,” he said. “Bring me my damn son!”

Eventually, Malachi’s parents learned the whole story.

Malachi was in art class, drawing Sonic the Hedgehog when, as Malachi remembers it, another kid came over and said his drawings “sucked.”

The boys started shoving, and their teacher called security. Malachi’s parents, who reviewed surveillance footage of the incident, said their son was led outside the classroom. When he resisted by sitting down, he was restrained by the security officer, dragged down the hallway in front of other students and eventually handcuffed.

Malachi, scared and confused, prayed to God for help.

“Please let me out.”

No charges were filed. The Pryors grabbed Malachi and his younger brother, drove away from the school and went to Uno Pizzeria. Anything to ease the misery of that day.

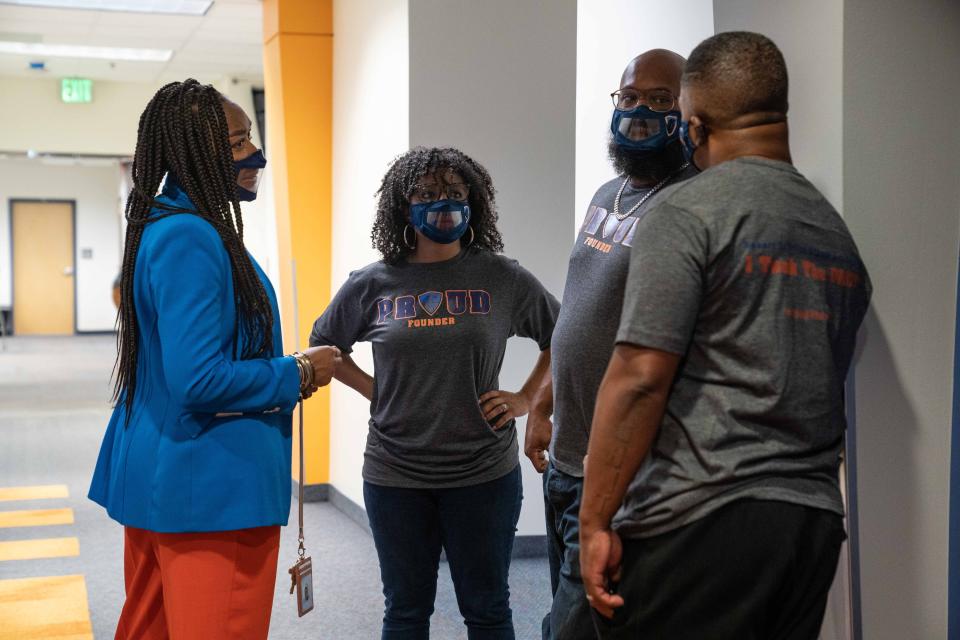

The incident drew fierce outcry in the community because Malachi’s parents were Brandon and Samantha Pryor, co-founders of Warriors For High Quality Schools, a community organization demanding racial justice within the Denver public schools system.

The Denver school board unanimously passed a resolution to eliminate the use of handcuffs with elementary school students in most cases and reduce the use of handcuffs with middle and high school students.

The school district agreed to a confidential settlement with the family before a lawsuit was even filed.

School resource officers and private security companies have come under fire for years, with advocates insisting that they are heavy-handed, don’t always know how to handle children and give overburdened teachers an easy way to deal with discipline. Then those discipline problems can become criminal problems.

Adding police to the equation doesn’t work because many have no idea how to deal with kids and are doing what they were trained to do — arrest people, said Leona Lee with the John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

“You bring in the police and security elements and demand absolute obedience,” she said. “The only way for them to deal with problems is to arrest people. No negotiating.”

Meanwhile, many children of color feel unsafe around police because they’ve seen friends or relatives targeted by law enforcement. They’re also aware of the police killings of Black people like George Floyd, Tamir Rice or Philando Castile, said Andrew Hairston with Texas Appleseed, a criminal justice nonprofit.

Still, many teachers support cops in schools. A June 2020 Education Week survey showed that just 23% of educators supported removing armed officers from campuses. And they point to school resource officers like Pamela Revels to show how effective they can be.

Revels — who is on the board of directors of the National Association of School Resource Officers — has been a school resource officer for all school ages in Lee County, Alabama, for 17 years. When a child acts out, she lowers her voice, lets the child know they’re safe and tries to get to the root of the problem, she said.

In one case, a boy was getting upset with a teacher because he was frequently marked late for class. Revels stepped in and discovered the child was too short to see the combination on his top locker. That day, Revels helped him move all his stuff into a bottom locker.

“Not another tardy, not another problem,” she said.

USA TODAY’s analysis goes much further than a 2007 FBI report scrutinizing the arrests of America's youngest students. The newspaper's analysis brings available numbers up to date and provides more detail. It shows that small children arrested at schools are disproportionately male; nearly two-thirds of the arrests were for assault; and most of the victims in those cases were adult females, presumably teachers and other school staffers.

Meanwhile, Black children were arrested at far higher rates than their numbers in the general population.

Many blame the arrests of small children on the proliferation of police in schools. There are more than 50,000 full and part-time school resource officers in schools around the country, according to 2015-2016 data from the National Center for Education Statistics. And schools with police reported 3.5 times more arrests than schools without them, according to a 2019 report from the American Civil Liberties Union.

At the same time, millions of students attend schools without counselors, nurses, social workers or psychologists.

But Revels has had extensive training on working with children, while many school resource officers do not. Thirty-eight states and territories either require school officers to have specialized training, encourage it or have policies not compelled by law, according to 2019 numbers compiled by the National Association of State Boards of Education. The remaining states don’t address it.

Staci Adams, a fourth grade math teacher at Smothers Elementary School in Washington, D.C., adamantly opposes child arrests but supports police in schools. She’s been through a lot over the years. She went to the hospital once for a shoulder injury after blocking a desktop a child threw at other students. A second grader who tried to strangle a principal with a lanyard is still in her school two years later.

Neither of those children was arrested.

Adams trains other teachers on how to handle challenging behavior, and she can deal with most situations herself. But she is not allowed to break up fights. She can’t restrain children. For a long time, she worried that a child might escape her classroom, run down the nearby stairs and race outside.

In December, it happened. That day, a child attacked Adams and destroyed a radio, then sprinted out of the classroom, down the stairs and through a door leading outside. Then he ran into traffic.

The school security officers chased him down, kept traffic at bay and were eventually able to get him back into school.

"They were able to keep the boy from getting hurt in oncoming traffic," Adams said. "They were able to keep him from harming me or any other students."

When the police were called, they offered Adams the chance to press charges. She refused, knowing that putting a little Black boy into the criminal justice system would hurt more than help. Instead, Adams and the family came up with a plan to control the child's behavior.

The boy later returned to school with a tearful apology, a card, a CD player and a promise to never act out again.

"Heal, learn and move on," Adams said of her philosophy.

Malachi’s mother, a lawyer who worked on the handcuffs policy with the district, said the incident traumatized the whole family. In the months that followed, she watched Malachi start to believe he was a bad kid. Good kids, he thought, didn’t get handcuffed.

It took therapy and numerous conversations with Malachi for the truth to sink in: You’re not bad. They should not have done that to you.

Brandon Pryor, who had already been a thorn in the side of the district with his activism, took his passion to the next level. He, Samantha and their friend, Gabe Lindsay, designed a district school founded on the values of Historically Black Colleges and Universities: The Robert F. Smith STEAM Academy. The vision is to empower, educate and inspire children of color instead of making them vulnerable to discrimination and arrest.

The Pryors’ advocacy is among many efforts underway to do away with the arrests or criminalization of young children.

In 2020, Virginia became the first state to prohibit police from charging students with disorderly conduct at school or school-sponsored events.

Some school districts, including Oakland and Los Angeles, have eliminated or reduced the use of law enforcement in schools. Milwaukee canceled its contract with the city police, but continues to call in officers to handle problems.

Specialists are teaching school resource officers how to recognize disabilities in children, how to read their behaviors and how to de-escalate outbursts.

“We were the right-wrong family who this happened to,” Samantha Pryor told USA TODAY. “It was terrible, but our child is strong and supported by two parents who know how to advocate for him. Some people just have to accept what the system does to them because they don’t have the resources to fight back.”

‘They move on. We can’t’

Kaia’s family refused to just accept what had happened.

Kaia’s mother, Jaime, moved from the Bahamas to Orlando shortly after the arrest to help care for Kaia. Her aunt, uncle and grandfather also help out. Kirkland, who raised Kaia for years before Jaime arrived in the United States, works at a bank to support the family.

After Kaia’s arrest, her grandmother became the public face of a movement to stop child arrests in Florida. She spoke to the media, to colleges and state legislators. She talked to other parents in similar situations. She filed a lawsuit against the school, which is ongoing.

In the meantime, the family is struggling.

They’re burning through Kirkland’s retirement savings. They have six open lines of credit and loans and set up a GoFundMe account. They’ve dealt with depression. They go to family therapy to deal with the constant stress of fighting to keep Kaia safe. Kirkland has been in the hospital multiple times, her medical problems agitated by stressors she can’t escape.

“Nobody thinks about how people’s lives have to go on after this,” Kirkland said. “They say, ‘Oh that's terrible,’ and they go on with their lives. Everybody sweeps you under the rug, and they move on. We can’t.”

Kaia still gets violent when she’s angry and runs away when afraid. She sees a therapist and a psychiatrist. She takes medications to help her with her anxiety, phobias and PTSD. She is still terrified of police.

She has attended three different schools since her arrest. She first went to a private school, but that proved too expensive. Kaia started at a new public school in August 2021 but quickly withdrew after Kirkland said a police officer was summoned when the child threw a tantrum. Kaia was restrained, taken to a hospital for a psychiatric evaluation and let go that day, Kirkland said.

Now Kaia attends a public school in Orlando that specializes in children with mental, physical and developmental challenges.

Less than a week after starting there, Kaia felt so overwhelmed by her schoolwork that she ran out of the school screaming for her mother and grandmother. A half-dozen staffers gave chase but knew not to touch her. They just made sure she couldn’t get off campus while the school called Kirkland.

As soon as Kaia saw her grandmother, she dropped to the hot asphalt exhausted, heaving and panting in the sun. “She was still screaming and crying and yelling, ‘No, no, no,’” Kirkland said.

Welcome to Kaia’s amygdala – the part of the brain that helps regulate emotions. When a person feels threatened, the amygdala triggers an involuntary fight, flight or freeze response. Then, when that danger disappears, the brain gets back to the business of controlling routine feelings.

But Kaia — like others who have experienced PTSD — is different. Her trauma has become stuck in the amygdala, creating emotional explosions. When something upsets her, her fight, flight or freeze response kicks in.

When she sees a cop, she hides, cries and shakes. If she feels attacked by a teacher, she’ll throw things or scream. When she broke her grandmother’s phone, she ran into a thunderstorm and raced through the streets, trying to find her aunt and buy a new phone.

This is what Kaia lives with two years after she was arrested at age 6. Her brain has physically changed, said her counselor, Nancy Langford.

“Arresting a child has the potential to create lasting, traumatizing stress,” Langford said. “The confusion of a young child being arrested may result in a lack of trust in people children are supposed to trust, such as teachers, police officers, even adults in general.”

At her new school, Kaia gets the specialized attention she needs.

“They are working wonders,” Kirkland said. “For the first time in two years, Kaia is excited to go to school.”

Another triumph came last year when Kaia’s family successfully pushed Florida lawmakers to pass the Kaia Rolle Act. It prohibits the arrest of any child under the age of 7 for anything other than a forcible felony. That’s still far too young, Kirkland said. She won’t be satisfied until legislators raise that age, preferably to 12.

Kaia knows about the law in her name and said she’s happy because her friends can’t get arrested.

“Everybody’s important, not just one person,” she said. The words were delivered without a smile or inflection, sounding more like a spokesperson accustomed to cameras and sound bites than a child.

Now and then, signs of the old Kaia unexpectedly emerge.

One day while watching YouTube videos in the family room, Kaia overheard her grandmother and mother talking about her in the kitchen.

The old Kaia was a burst of sunshine. She owned the room, no matter where she went. Just look at these pictures of her. Look at that smile. Wasn’t she beautiful? Oh, there’s her with her keyboard. She sang and made up songs all the time, all the time.

Kaia poked her head around the corner. Slowly, she padded over to the kitchen bar and stared at the photos on her grandmother’s phone. Her mood visibly brightened while she commented on the changing images.

“Look at me with my long hair,” she said, clinging to her mom. Kaia has her own Facebook page, filled with scores of pictures of herself as an infant, a toddler and a schoolgirl. She seems especially fascinated with photos taken before her arrest.

“It’s like, I think she wants to return to that girl," Kirkland said, "but she doesn’t know how.”

Contributing: Kaitlyn Radde and Emma Uber.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: School arrests include kids as young as 5. Why does that still happen?