She lost her husband, then her son, daughter and mother. What's left for Chris Hanes? Her faith

YORK, Pa. – Christine Hanes doesn't languish in what once was.

She doesn't compare her life now to the one she had with a full house with her husband and three kids because that would magnify the ache in her heart.

Instead, she lives for today, for her family, her church, her job and the new home she found after her husband and son died in the same year.

She has been on what she calls a "journey" for the last four years. While it's been anchored by tremendous grief, including the loss of one of her daughters and her mother, her journey has also seen days of great joy and personal satisfaction, all of it resting on a foundation of faith.

She doesn't tell her story often because she doesn't want people to feel sorry for her.

"I don't want to be known as the woman who lost her husband and her son and her daughter," Chris said. "I want to be an inspiration."

'He melts my heart'

Ryland Harpster's blond hair falls around his tiny face as he watches a movie in his grandmother's living room. He plays with his toys and occasionally walks to his "Mimi," just a few feet away to ask for something to eat or to fix a toy.

"He melts my heart," said Chris of her youngest grandchild, the only child of her daughter Alysia, who died in April.

Chris' home is a comfortable three-bedroom house . Photographs of her family cover the walls along with quotes about family and faith.

She had spent years living as a caregiver in a house retrofitted to accommodate her paralyzed son and her husband, who had Lou Gehrig's disease. When they died, she wanted to get out of that house – too big, too much for her.

This house reflects the new life she has built in the wake of her losses.

The best of times

Chris met Lee Hanes at a fish fry, organized by the manager of an apartment complex where they both lived. The next day, Lee, who owned a construction company, invited her on a motorcycle ride.

"Two weeks later, he proposed. Eight months later, we were married," she said, smiling. They married on Valentine's Day in 1987.

Chris already had an 8-year-old daughter, Michelle, from a previous marriage.

"Michelle wouldn't give him the time of day. That's one of the things I liked about him. He accepted her. He included her in everything he did," she said.

Their daughter, Alysia, came along in 1988 and, three years later, they had Matthew.

Since he was a toddler, Matthew talked about the military. As a junior in high school, he started talking seriously about following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather in the Army.

He graduated from high schoolin June 2010 and left for boot camp later that month, on his 19th birthday. He went into the airborne infantry.

"We went to Fort Benning and watched guys jumping out of airplanes for three days, just jumping out of planes and folding up their parachutes and running back to do it all over again," Chris said. "He loved it."

The phone call

Matthew deployed for Afghanistan in February 2012. On June 22, Chris talked to him, as he prepared for a mission the following day. She took comfort in knowing that they would be the second platoon out; his platoon wouldn't be in the lead.

The next morning, Chris was at the grocery store when her cellphone rang. It was someone at Fort Bragg to say that Matthew had been shot.

Calmly, Chris said she made all the important calls to deliver the news of her son, her baby. He had been shot, but he was alive.

Over the next five days, the Army fed information to the family. He had been shot in the neck and had some paralysis, but no one knew how severe it would be.

Doctors put Matthew in an induced coma to stabilize him for the trip from Kandahar, Afghanistan, to Germany, and then to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

Chris and Lee arrived at Walter Reed just as Matthew was being taken into his room. As he awoke from his coma, his parents had to explain where he was and why he was there. It was very emotional, Chris said, but Matthew remained calm.

"He was an amazing guy. He had been an amazing child," she said. "He was never angry."

Not angry at what happened to him. Not angry at his prognosis.

The boy with a contagious smile and a great sense of humor was paralyzed from the chest down. When one of his superiors called and told Matthew he hadn't slept since the shooting. Chris heard Matthew tell him: "I don't blame anyone. ... Shit happens."

Chris was blown away, she said. "They were the words that made me know that he was gonna be OK."

'I can't do this by myself'

Few friends outside the military visited Matthew at Walter Reed, probably because they didn't know what to say, Chris thought.

Even fewer people could visit when the Hanes moved him to Tampa, Florida, for rehabilitation. They wanted him to be somewhere warm with sunshine to brighten his days, but they were far from family and his brothers in the military.

Chris stayed with him at James Haley Hospital for more than seven months, and it wore on her. People she met along the way asked how she was, but those acquaintances were preoccupied – they were rushing to the bedsides of their own loved ones.

Her anxieties were overwhelming, so she handed it over.

"I was like, I can't do this anymore. I can't do this by myself anymore. God, you have to do this," Chris said. "I handed it over, and it was such a relief."

Four loved ones

A mass of people welcomed Cpl. Matthew Hanes home. Friends, neighbors and strangers lined the streets, greeting him and his family on their return. In their front yard alone, Chris guessed 300 people patiently waited for their arrival.

"It was very emotional, overwhelming," she said.

Add that hero's welcome to other acts of grace: The Warrior Brotherhood Veterans Motorcycle Club had helped Lee Hanes redo their home for Matthew: elevator, exercise room, conversion of a two-car garage into Matthew's bedroom and construction of a four-car garage. And while she was in Florida, Chris had received paid time off for all those months from her employer through vacation and sick days she had accumulated. Her co-workers donated vacation days as well.

They were gifts of kindness that touch Chris still today.

Matthew's hands, torso and legs remained paralyzed despite exercise and rehab, but he held out hope that he would regain movement. He looked into stem cell research and found a hospital in China that would perform a treatment. It didn't help, Chris said, because they had found his spinal cord was too collapsed.

He enrolled in college courses, studied military history and opened a firearms business.

Chris had seized his new life, but his father had begun to worry about his own health.

Before the shooting, Lee had been suffering from breathing problems. Once his son was home, he started to see doctors again for a diagnosis. At Hershey Medical Center, a specialist said he would have an answer for them that day. Chris turned to Lee and said: "This is not going to be good news."

It wasn't. He had Lou Gehrig's disease, or ALS, a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects nerve cells in the brain and the spinal cord. There is no cure, and it is eventually fatal.

"He lived on a farm all his life," Chris said. He rode a motorcycle and worked in construction before taking physical labor jobs with Northeastern. "He was a tough person on the outside, but if you ever got a chance to know who he was, he had a very soft heart."

Lee's battle with ALS ended a year later, on April 4, 2015.

Without her spouse of 28 years, Chris wanted to move out of their five-bedroom home, but Matthew talked her out of it.

Four months later, Matthew had two friends over, watching wrestling late at night. At 2:30 a.m., when they left, Chris put him in bed and asked if he wanted his medicine. He said he didn't, but after she got him settled, he said, "You know, mom, I think I'll take those pills because I don't feel good."

Those were his last words.

A blood clot had stopped his heart. Chris gave him chest compressions until paramedics arrived, then he was put on life support at the hospital.

"They said he would never wake up. He would always be like that, and I made the decision to take him off of the machine," Chris said. She didn't want to prolong the decision because she didn't want her daughters to ever have to make this choice.

His death had been a shock. He had been doing well, although complications are always possible with paralysis patients.

"You can always ask, 'What if?' But nothing will bring them back. His time was up," Chris said.

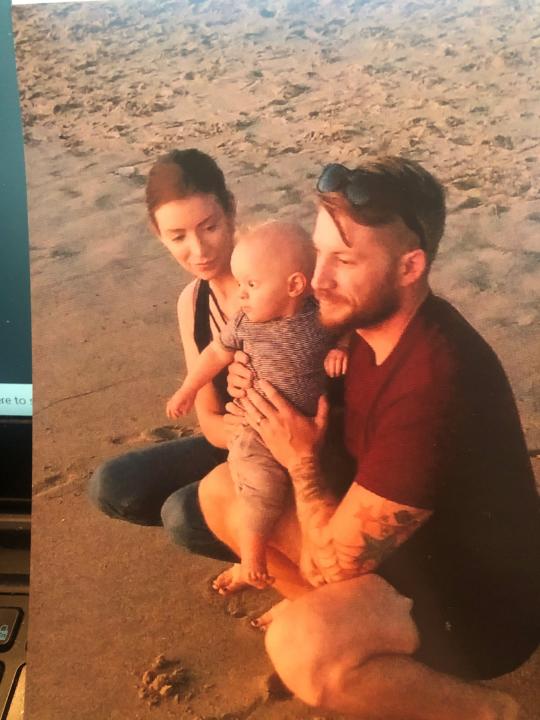

A year later, her youngest daughter, Alysia, was diagnosed with glioblastoma, a brain tumor. She was 26 weeks pregnant during the surgery to remove the tumor. Then doctors delivered baby Ryland two months early so Alysia could undergo radiation and chemotherapy treatments.

She traveled from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, every day by train to be with Ryland at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia in the midst of her treatment.

By August of that year, an MRI showed no signs of cancer on Alysia's brain. She and her husband, Geoffrey, decided to move to California with Ryland, but three weeks after moving, her symptoms returned. Another tumor was removed in June 2018, then another six months later.

Chris flew back and forth to California to help care for her and the baby, but she finally told her son-in-law, "Your support system is back home."

They returned to Lancaster, and earlier this year, Alysia was diagnosed with another form of rare brain cancer. She died in April.

"She had a positive attitude," Chris said. "I've never seen her angry. I think she came to terms with it."

Above Ryland's crib in Lancaster, a quilt of photographs depicts his life with his mom.

And just two months ago, Chris' mother also lost her battle with pancreatic cancer after a two-year fight.

"Life continues, with or without them," Chris said. "You have to learn to live with the pain."

Keeping the faith

It was two years after her son and husband died that Chris joined a grief support group. She now helps to lead the GriefShare group at St. John Lutheran Church, where she works part time as a ministry assistant. She retired from Northeastern nearly a year ago.

"I feel for people who don't have the support. I don't know how they do it without support and without faith," Chris said.

"Reach that hand back and help someone else," said bereavement specialist Leslie Delp. It's what turns grief into a positive action, helping others.

Delp, who founded the Olivia's House organization in Pennsylvania to support grieving children, lost her son when he was a baby.

"I am a bereaved mother, but it doesn’t define me," Delp said.

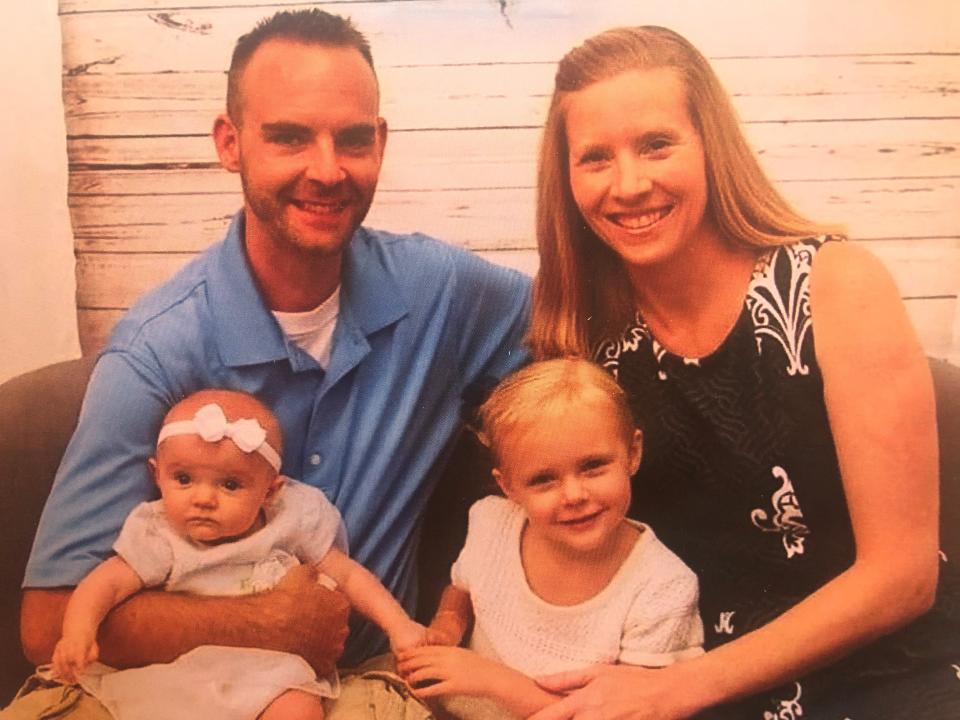

Chris' daughter, Michelle Overmiller, husband Dan, and their children Addison, 5, and Emily, 2, along with Ryland and his dad are the new foundation in Chris' life.

"There are still mornings I wake up, and the pain is bad," Chris said. "I still have my moments when I cry because I miss Lee or Matthew or Alysia or look at (Ryland) and know he'll never know her. Or see my dad, after 60-plus years of marriage and be by himself.

"It's God's story, and he's writing it. The people he puts in that story are a gift to us and not ours to keep. I'm thankful for the years I had with each and every one of them because some people don't even have that."

A FedEx worker walked 12 miles home for months: Co-workers rally to buy her a car

A dog and deer played together in a Michigan yard: A teen caught the moment on video

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: Pennsylvania woman's husband, son, daughter died. She's kept her faith