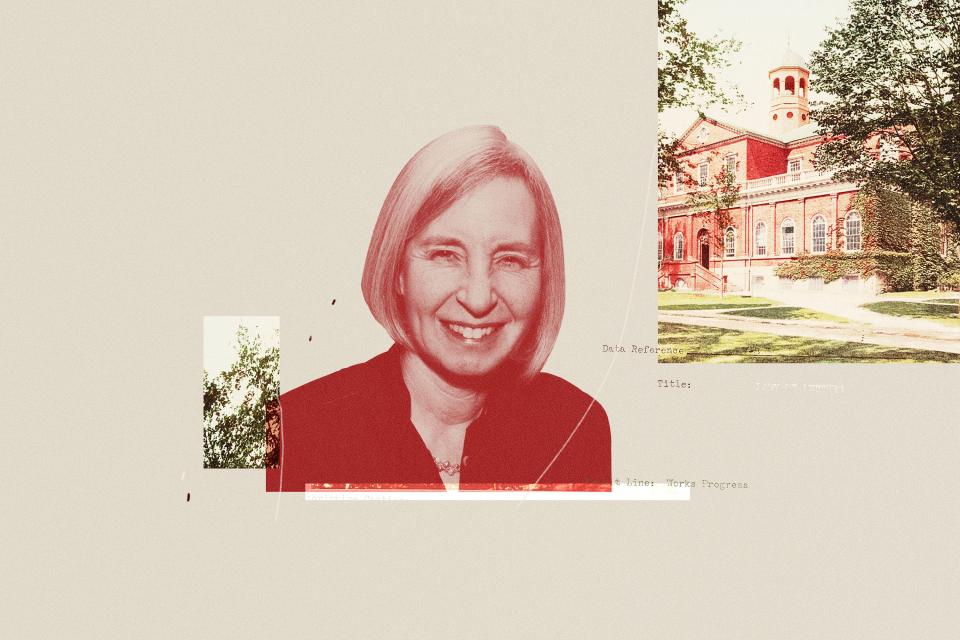

She ran Harvard Law School and mentored future politicians. Now she wants them to get along

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In February 2020, Martha Minow stepped up to the podium at a U.S. State Department conference to address a task force assembled by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to reassess the role of human rights in foreign policy.

The year before, the group, called the Commission on Unalienable Rights, had generated controversy, releasing a report that many argued imposed a hierarchy on human rights, undermining the rights of women and members of the LGBTQ community. Minow had testified about her own concerns with the report (a consummate professor, she gave it a C+).

But in her presentation, she wanted to give a speech on a subject that would elicit agreement in the room. So she spoke for 30 minutes about human dignity.

“Respect for individual dignity means resisting efforts to dehumanize any individual or group or to deny ... their rights simply because of their race, gender, identities or other circumstances,” Minow said in her remarks. “Rules of social order, to be enduring, depend on recognizing the dignity and worth of other humans.” She recalled a shift toward a fuller awareness of other persons’ inherent humanity when she became a mother.

“This is somebody’s beloved child,” was the thought she returned to when dealing with someone who seemed offensive or difficult.

“Rules of social order, to be enduring, depend on recognizing the dignity and worth of other humans.”

Minow — a former dean of Harvard Law School, a 300th Anniversary University Professor (the highest honor a Harvard professor can receive) and a leading authority on human rights law — thinks a lot about what it means to honor the humanity of each individual, particularly those too often marginalized, and what happens when dignity is denied.

She studied the origins of ethnic conflict in Kosovo and worked with the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees to chart possible ways forward for post-conflict societies in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda.

Minow, 68, is drawn to the reciprocal nature of dignity and its potential for fostering a society where people with different views and identities can live peacefully. “In the U.S. legal system, we’re very focused on individual rights, but rights are actually a way to think about relationships. We don’t have rights apart from other people,” Minow told me when we met in Griswold Hall on the Harvard Law campus, where she has taught since 1981.

Respect enables individuals and groups to find ways to live alongside each other even when they don’t see eye to eye. Differences of opinion can become especially acute in conflicts that arise between groups based on their sexual, racial or religious identities. Minow, who is Jewish and who deeply cares about LGBTQ and women’s rights, has wrestled with these kinds of complex situations, where it can seem difficult or even impossible to reconcile clashing freedoms and rights.

But perhaps surprisingly for a law professor, Minow believes the best way of settling these conflicts is not in court, which can often inflame the situation. Instead, Minow proposes an alternative solution, anchored in finding points of overlap between disagreeing sides. And at its core, this solution begins with listening.

When we met, it was the last day of spring break at Harvard and the campus was empty apart from a sprinkling of tourists and grounds crews. Minow had just gotten back in town from Montgomery, Alabama, where she met with the board of the MacArthur Foundation (known for its “genius grants’’), which she’s served on for nearly a decade and now chairs. The group was there to learn from the National Lynching Memorial and Legacy Slavery Museum.

John Palfrey, MacArthur’s president and Minow’s former student, told me she has a gift for approaching any project with sharp intellect but also empathy. “She really connects to ideas, people and places,” he said. “And she’s deeply seeking to understand the effects of history and how it touches people.”

Minow’s office is lined with bookshelves and two large windows that today overlooks a bleak courtyard exhausted by Boston’s joyless March weather. A vibrant blue wall is visible from behind the books. Minow, who loves Cape Cod, chose the color to remind her of the ocean. She honeymooned on the Cape with her husband Joseph Singer, a Harvard Law professor who focuses on property and American Indian law.

Minow unwraps a package that arrived for her while she was gone, a gift from Gordon Smith, the dean of Brigham Young Law School. It’s a 10x8 reproduction of “Forgotten Man,” a painting by Maynard Dixon that belongs to the Brigham Young University Museum of Art collection. In the painting, a somber man sits on the curb, his body slouching, as pedestrians behind him march on.

Minow first encountered the painting in the office of Dallin H. Oaks, first counselor in the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, when the two met in Utah in January during her visit. The painting has adorned President Oaks’ various offices since his days as BYU president nearly 50 years ago.

Minow was struck by the image and discerned in it an elusive reminder for her own work. It’s easy to feel remote from social problems she writes about, she says. “It’s important to remember that there are human beings behind every one of the lawsuits that I teach about and social issues I work on,” she told me. Minow’s ideas on possible solutions to conflicts between religious freedom and protections of minority groups have also made an impact on President Oaks — he quoted Minow in his 2021 speech at the University of Virginia, which he called the most “difficult” speech he’d ever given.

Related

How religious engagement increases freedoms around the world

How a target of religious bigotry and racism found a higher way

Although the two had not met until a few months ago, Minow had long shared her father’s admiration for President Oaks. Newton Minow, Martha’s father, advocated for President Oaks to succeed him as the chair of Public Broadcasting Systems, despite skepticism from the board about President Oaks’ Latter-day Saint faith. “My dad was furious,” Minow recalled. “He said he’d hold a press conference and say this is happening.”

Growing up in the Chicago suburbs, the dinner table conversations in Minow’s home revolved around the big questions of society. Her father, an accomplished attorney and former chair of the Federal Communications Commission, would bring up the cases he worked on. Minow’s mother, Josephine, a Chicago school teacher, political advocate and philanthropist who died last year, talked about her work with juvenile justice issues and various cultural initiatives. Minow’s parents encouraged her and her two sisters to voice their opinions. “I guess from an early age, I learned to have a sense of obligation and an opportunity to participate in public events,” Minow told me.

On the wall in her office is a framed image with the words by the rabbi known as Hillel the Elder: “If I am not for myself, who will be for me? If I am only for myself, what am I? And if not now, when?” From early on, Minow’s faith oriented her toward the history of oppression on the basis of religious identity. As a first grader, she recalls being puzzled by the Christian prayers recited at her school and being excluded from the “friendship circle” because she wouldn’t say the prayers with others. These experiences contributed to Minow’s growing sense of obligation to stand up for people who may not be Jewish, but similarly have faced marginalization and exclusion from society. “It’s part of my upbringing to recognize there is a universality to human experience,” she said.

“How can a pluralistic society commit to both equality and tolerance of religious differences?”

When Minow began teaching in 1981, the questions of religious liberty were in courts. In her class on children’s rights, she recalls teaching about the conflicts of parents opposing their child’s medical treatments because of their religious views and the detrimental effects of refusing those treatments.

“How can a pluralistic society commit to both equality and tolerance of religious differences?” she asked in her 2007 paper on whether religious groups should be exempt from civil rights laws. The tensions are profoundly challenging, she tells me. When two constitutional values clash — both “plural goods” as she refers to them, both core to American democracy — what’s the way forward?

“Free exercise of religion is rooted in the constitutional tradition, and unbounded deference to religious beliefs could destroy vital public policies and law,” she said in her speech at Brigham Young Law School in January. “The core American commitment to equal treatment of individuals combating discrimination and exclusion based on individuals immutable characteristics is also paramount in American law and ethos.”

Instead of going to the courts, Minow argues for coming together with a focus on shared interests

“Let’s start with finding where we overlap,” she tells me. Finding the point of convergence through negotiation and accommodation — mindful of both sides’ “non-negotiables” — can often lead to productive solutions. The courts are not equipped to deal with these kinds of nuanced conflicts between the state and religion, she argues. “When you go to court, they don’t say ‘let’s work it out,’” she said. “These are not ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions. These are very complicated issues.”

She points to some successful examples of negotiating these kinds of disagreements. When the city of San Francisco refused to partner with organizations that didn’t offer health coverage to gay couples, Catholic Charities and the city negotiated a solution. With the shared goal of advancing health coverage in mind, the city officials and the archbishop agreed on a new interpretation that allowed an individual to extend health coverage benefits to an adult in their household.

Minow touts the “Utah Compromise,” the 2015 landmark legislation backed by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that supported religious freedoms and LGBTQ antidiscrimination in housing and employment as a concerted effort of finding common ground. “These are the approaches the court can’t give,” Minow told me.

“Free exercise of religion is rooted in the constitutional tradition, and unbounded deference to religious beliefs could destroy vital public policies and law.”

I ask Minow why the legislation passed in Utah. “You know, I’m not a Mormon. But I do understand that a part of the (Latter-day Saint) theology respects democracy, respects the Constitution and understands that pluralism is an important part of being able to live together,” she said.

Thomas Griffith, a former judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, began corresponding with Minow during her tenure as dean, taking her recommendations for law students to hire for clerkships. A Latter-day Saint, Griffith sees Minow’s approach echoed in his faith’s commitment to affirm religious freedom and protect LGBTQ rights. “That’s the animating spirit of the church’s emphasis on fairness for all,” he told me. The approach is risky, a kind of gamble, he acknowledges, because it requires a concerted effort on both sides. “The hope is that if you reach out to the other and show them respect and that you’re interested in protecting them, they will reciprocate,” he said.

Minow says there is no magic wand to wave in any of these situations. But it’s possible to lower the intensity and hostility by separating the disagreement on an issue from the dignity of the person holding the view with which we disagree. “Then we can move to offer respect to people even if we really, really disagree with them,” she said. “And that means listening and being open to the possibility that we don’t understand.”

This kind of intellectual openness enables Minow to more easily grasp the different dimensions of a social problem she may not see fully at first. She recalls being skeptical about publicly funded school vouchers that allowed children to enroll in religious private schools. The issue to her initially presented the erasure of boundaries between church and state. But then she saw who was supporting the vouchers: it was parents from low-income Black communities. To her, it was a sign that she may be missing something. “Who am I to say this is a bad thing?” Minow said. “If they don’t have options in their school system and they think this would be better, I need to learn about that.”

On a recent evening, Minow was on the phone with a former student, now a professor, sharing advice on what makes a good mentor. Minow’s former students — dubbed “Minow mentees” — are judges, professors, CEOs and academics across the globe. The list famously includes former President Barack Obama, who called Minow “a teacher who changed my life.” Some academics, Minow tells me, choose to impart their school of thought or belief system upon emissaries, who then go on to replicate it. “That’s not what I do,” she said. “I try instead to listen and support what it is the student wants to do and how they want to explore their ideas.”

Related

How Minow is able to attend to so many commitments is a mystery to Randall Kennedy, Minow’s colleague at Harvard Law School and a co-editor on a legal journal they launched. (She doesn’t need much sleep, she tells me.) Minow has been there for Kennedy in challenging times. When the pandemic struck, the two talked on the phone every Saturday at noon. “In that frightening moment that meant a lot,” he said. When Kennedy’s wife died in 2005, Minow was there to help out and be there for him emotionally. They’ve been close for years: both went to Yale Law School, clerked for civil rights lawyer and Supreme Court Associate Justice Thurgood Marshall, and exchanged marked-up drafts of their writing. “She’s a thoroughly humane, extraordinarily empathetic person,” he said.

These days, Minow thinks a lot about existing divisions among Americans. “I worry that we are so polarized, that there’s such demonizing of people on both sides. That is exactly the recipe for a civil war,” she said. And the news algorithms and social media are only contributing to divisions by amplifying extreme voices. “People are fed these diets of very different and very hateful sources of information,” said Minow, who’s wrestled with alternatives for sustaining local news in her 2021 book “Saving the News.”

While tolerance and acceptance can jumpstart the difficult conversations toward consensus, they may not be enough, Minow believes. Forging a pluralistic society happens alongside an internal shift toward humility. “There needs to be belief that there is something good about having the possibility of learning from people who are different from yourself,” she said. “And cultivating enough humility that you don’t think you’re always right.”