What Happened After Nixon Failed to Appoint a Woman to the Supreme Court

“Mommy’s very mad,” said a crestfallen president of the United States.

Richard Nixon was on the telephone with his daughter Julie, who had called to congratulate him for his speech that night, naming William Rehnquist and Lewis Powell to the U.S. Supreme Court. It was October 21, 1971.

The nominations were a masterstroke by Nixon. The Senate would confirm the two conservative nominees; the South and big business would rejoice, and he would avoid the bruising he received when two previous nominees—Judges Clement Haynsworth and G. Harrold Carswell—had been rejected on charges of racial insensitivity and unethical behavior, in 1969 and 1970.

But along the way, Nixon had promised his wife Pat that he would name a woman to the high court. The first lady had lobbied him, privately and in public remarks. And so, when she heard Nixon name two men, she was furious.

That Pat Nixon was angry has been reported—most notably in Julie Nixon Eisenhower’s revealing biography of her mother. But until this year, when the Nixon presidential library released a fresh batch of previously expurgated conversations captured by the White House taping system, we’ve not been able to listen in on, or know the extent of this discord in the Nixon household.

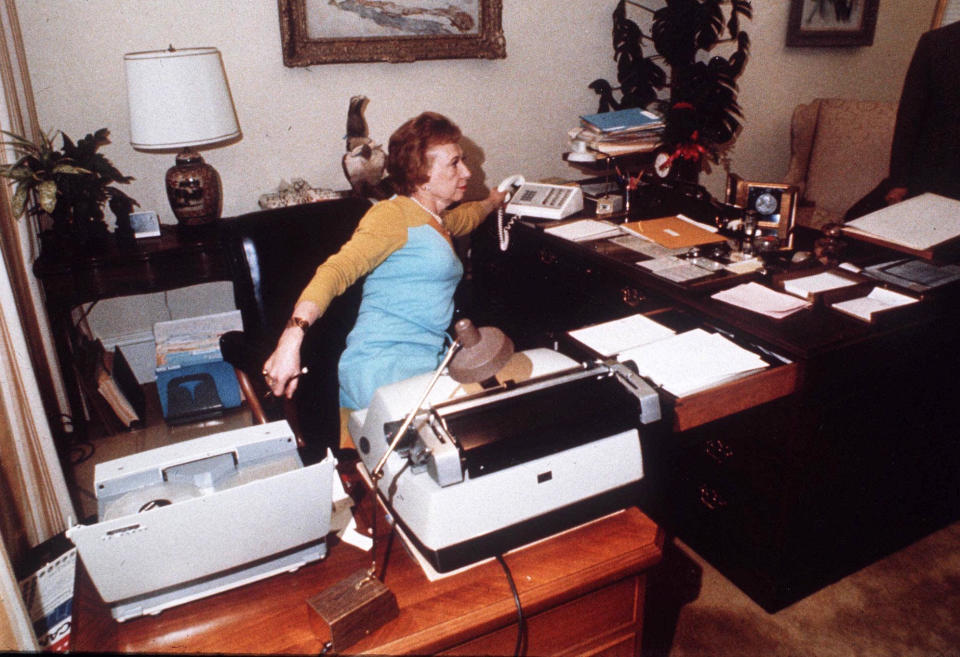

The president knew he had done bad. He didn’t call his wife to check on her reaction—he used a go-between, his longtime secretary Rose Mary Woods.

“Just to tell you what you’re in for,” Woods reported back. “This is personal for her … she’s really, really teed off.”

“She had been promised it would be a woman,” Woods told the president, and now Pat Nixon felt she “made a fool of herself.”

“She didn’t make a fool of herself!” Nixon replied. It was the chauvinists at the American Bar Association she should blame, not him. Their judicial qualification committee had given a proposed female nominee, California appellate Judge Mildred Lillie, a cold shoulder.

Without the ABA’s endorsement, said Nixon, a woman would be rejected by the Senate. “It would hurt women, the cause of women, to have her turned down by the Senate!” he argued to Woods.

But Nixon was not the most intimate of fellows. He had a difficult time expressing feelings. And in this case, he paid for his propensity for avoiding personal confrontations.

“What she’s really upset about,” Woods told him, “is she went out on a limb … and she’s mad because you didn’t call and tell her yourself.”

Oy. Dick Nixon was in trouble. He did what many American males of his generation might have done: He drafted his daughters to argue his case.

“Julie could call Pat,” Nixon advised Woods. “Try Julie, will you?”

Before too long, Julie was on the phone with her dad.

“Mommy’s very mad,” he told Julie. “Mommy said she is hurt because I didn’t tell her.”

“The thing that is sad,” said Julie, is that “she thinks she doesn’t have any influence with you.”

Nixon coaxed Julie to tell her mother she should be blaming the ABA, not him.

“The main thing is not blame me!” Nixon told his elder daughter, Tricia, in a separate but similar conversation that evening. “We are preparing a woman for the next spot,” he promised.

Neither Julie nor Tricia appear to have shared their mother’s fury. They both—and Rose Mary Woods, too—seemed to take it in stride that the ABA was correct, that Lillie was not qualified and that, given the state of women’s professional advancement in the 1970s, there were no female candidates eligible for the court.

Woods told Nixon that when Pat had complained that her husband could have found another qualified woman, Woods had challenged her: “Who are they?”

And while Pat insisted to Woods that her husband should have ignored the ABA, and sent Lillie’s name to the Senate anyway, Julie and Tricia agreed with their dad that defeat was inevitable, and so to be avoided.

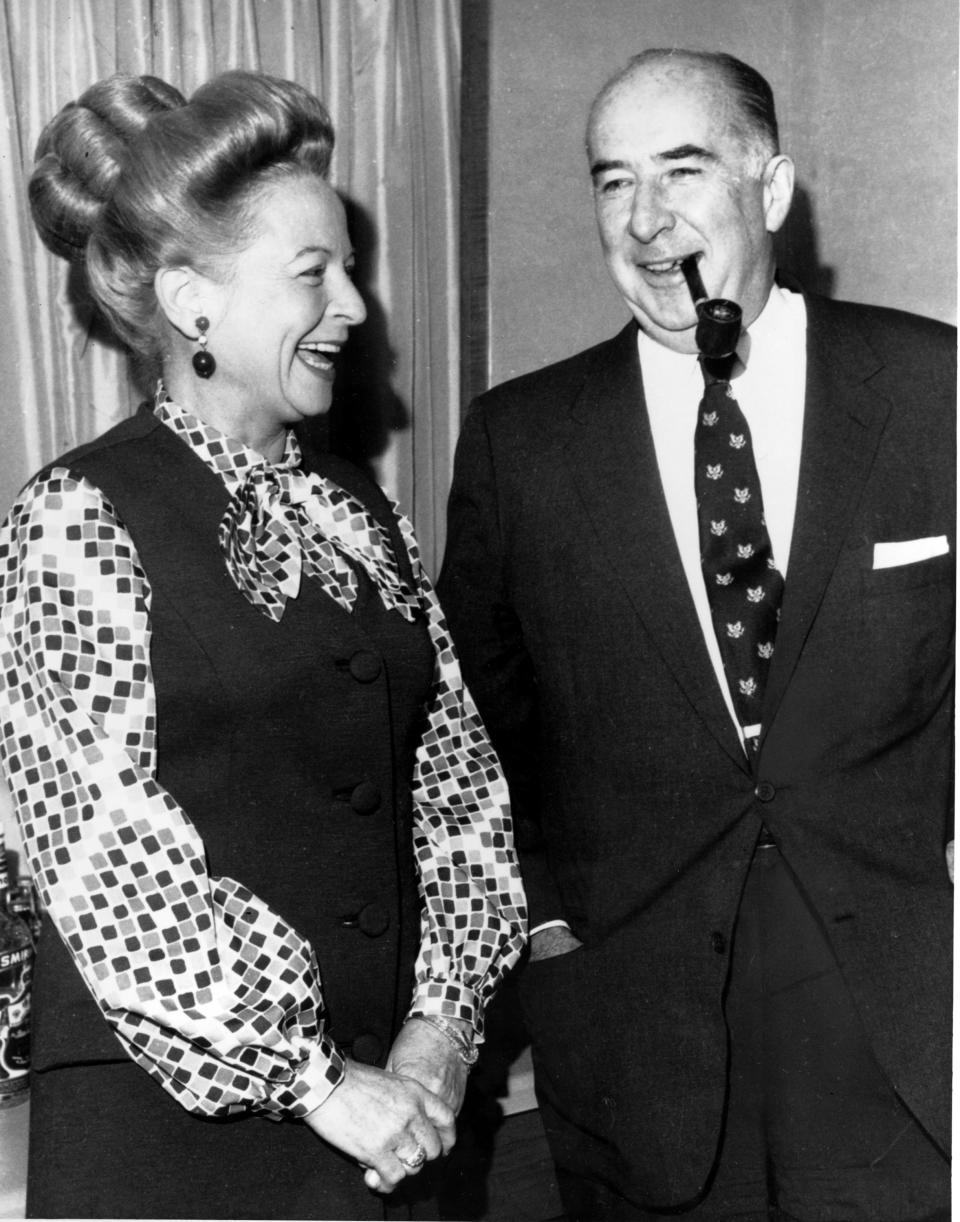

Like Ralph Kramden calling on Ed Norton, or Fred Flintstone commiserating with Barney Rubble, the president next phoned his friend, Attorney General John Mitchell.

“My wife is really put out,” Nixon said. “She is so goddamned mad.”

The attorney general, however, had problems of his own. His wife Martha—a notably outspoken woman—was raising hell in the Mitchell household.

“You think your wife is mad. My wife wouldn’t even talk to me,” Mitchell said. He had put the blame on the ABA too, to no avail. “That’s what I’m trying to tell Martha here for the last 20 minutes and I’m not getting across!”

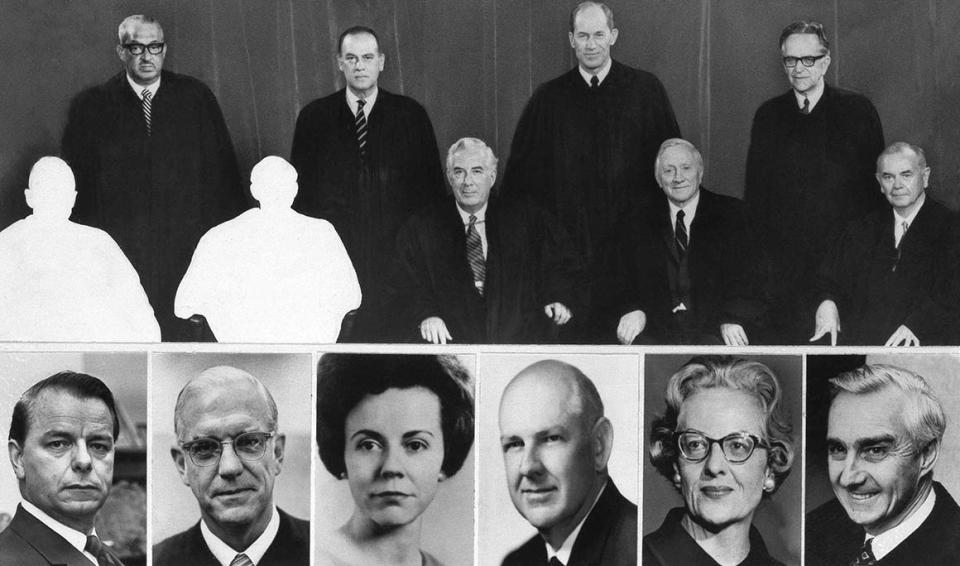

In the taped conversations with Woods, Mitchell and his daughters, Nixon expressed great satisfaction with his choices of Rehnquist and Powell, and no great regret that Lillie failed to impress the ABA. Rehnquist and Powell would help steer the Supreme Court to the right, contributing to landmark decisions that changed the course of American history. They replaced more liberal Justices Hugo Black and John Marshall Harlan who, aged and ill, had retired in September.

“We really threw a bombshell at those [liberal] bastards” in Congress and the media, he told Mitchell.

And “make sure to emphasize to all the southerners that Rehnquist is a reactionary bastard, which I hope to Christ he is,” Nixon said, in a segment of the tape that has been previously opened.

There appears no evidence, in the newly released segments of the tapes, that Nixon had deceived Pat, or—as some historians and commentators have argued, and other tapes indicate—that he never really wanted a woman on the court.

In fact, from a sense of guilt or fairness, he is heard telling Mitchell, with seeming sincerity: “We’ve got to have a woman, John.”

Next time.

“Tell Martha to calm down,” Nixon told his friend.

There would be no “next time” for Nixon, however. In his five-and-a-half years in office before resigning in August 1974, he named four Supreme Court justices to the high court. But Rehnquist and Powell were the last. The first female justice, Sandra Day O’Connor, was named by President Ronald Reagan in 1981.

The newly released portions of the Nixon White House tapes are part of the Nixon presidential library’s “re-release” effort, in which, with National Archives funding, the thousands of hours of tape recordings are getting a fresh look, with the goal of opening previously closed segments of conversations that dealt with politics and other matters. The batch from October 21, 1971 were opened in January.

As the late Benjamin Bradlee, the Watergate-editor of The Washington Post, once told me: “The tapes are the gift that keeps on giving.”