She swam the English Channel with lots of support from Mom (and a little from T-Swift)

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In the days leading up to the moment last Tuesday when Molly Sanborn found herself on a near-pitch-dark Samphire Hoe beach waiting to start her attempt to swim the English Channel, she thought of the many people who helped her get there — and the scores back home who would be cheering her on virtually as she tried.

After wading into the chilly sea at around 10 p.m., however, for much of the night the 29-year-old Huntersville native fought the urge to give up by fixating most of her mental energy on just two particular women.

One of them was one of the most famous singers in the world.

“I didn’t have a watch, so I’m not totally sure,” Sanborn says, “but I would guess from the hours of midnight to 4 a.m., I was just so cold and so disoriented. I was just like, This is REALLY hard. What the hell? I don’t know if I can do this. And during those hours, I sang a lot of Taylor Swift, and that did help.”

The other woman that stood out in her mind, like a lighthouse on a dark ocean, was her mother.

“One thing that I kept thinking about, in addition to all the Taylor Swift lyrics, was, OK, I HAVE to make it until daylight,” Sanborn says.

That’s because her mom — Kay Sanborn, 64, of Huntersville — had signed up to be Molly’s “support swimmer,” meaning she would periodically be allowed to swim alongside her daughter so long as she followed very specific rules. Those rules have a variety of rationales, some designed to prevent giving the person attempting the Channel swim any sort of significant aid, others focused on general safety. In this case, Molly was thinking about the rule that support swimmers can’t be in the water at night (since it’s hard enough to keep track of a single swimmer in the dark, much less two).

“So I was like, Mom has been training for this as long as I have,” Molly continues. “I have to make it until daylight and she can get in with me. ... She will have gotten a chance to go in. I can quit after that. It’s fine. I just told myself that for several hours.”

Finally, more than seven hours into what would wind up being a 14-hour-and-24-minute swim, the sky began to lighten. Around 5:45 a.m., the sun peeked over the horizon. Shortly after that, Kay got in and swam the first of two one-hour swims with Molly.

Molly may not have been any warmer physically, but she definitely was emotionally. She started believing that the goal she’d been working toward for the past 19-plus months — for which she’d done more than a thousand miles of training swims — was within her grasp.

She also knew, though, what anyone who’s ever tried to swim the English Channel knows: “It is not over till you hit sand.”

‘Well, pool’s open. I’ll go try this.’

The Sanborn family has a history of pursuing athletic feats that most people would never attempt.

Molly’s dad, Tim, has done the Grand Canyon’s strenuous North Rim-to-South Rim hike — which covers 24 miles, 6,000 feet of descent, and another 4,500 feet of climbing — in a single day (and two other times, in three days). Kay has two Ironman finishes on her resume, and in 2018 she completed Comrades Marathon, a legendary 55-mile race in South Africa. And it’s worth noting that she was talked into running Comrades by her and Tim’s eldest daughter, Hannah, an accomplished marathoner who wound up finishing 122nd out of 3,372 women in the field that year.

So none of them was honestly that surprised when Molly announced in January 2022 that she was going to try to swim the English Channel.

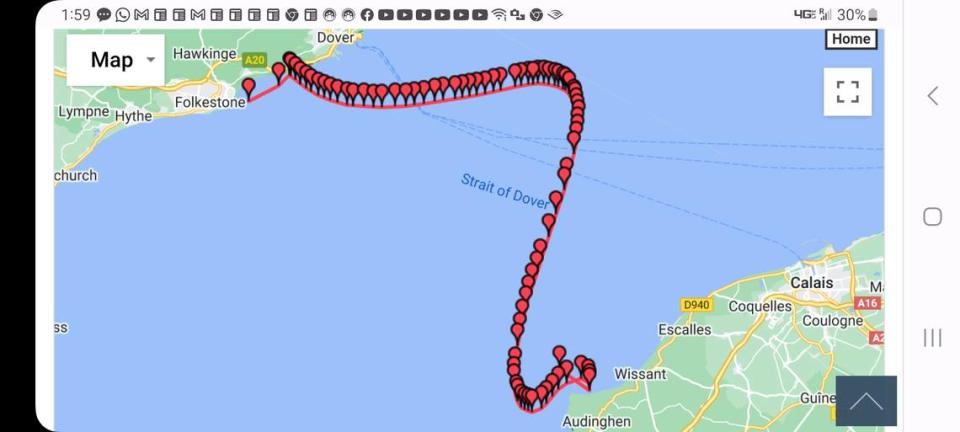

On one hand, it’s considered by many to be the ultimate long-distance swimming challenge due to everything from the unpredictable distance (if you could swim it in a straight line, it’d be 21 miles — but the shifting tides can add many more) to cold water temperatures than can dip down toward 60 degrees even in summer.

On the other ... insane athletic pursuits run in her family’s blood, obviously. And it’s not like she was a novice swimmer.

Molly was just 5 when she joined her neighborhood swim team, and went on to compete in long-distance freestyle events at both North Mecklenburg High School and for a club team at NOMAD Aquatics & Fitness Center in Huntersville. She started gaining experience in the open water via participating with her family members in relay divisions of local triathlons, fell in love with it, and by the time she was 16, she was racing (and winning) the 2.4-mile swim portions of Ironman-distance events.

Then, after high school, she stepped away from swimming for several years to focus on her bachelor’s in biology at the University of Richmond, then her master’s in public health at George Washington University. She picked back up a little bit while doing an internship in Malaysia between 2018 and 2019 ...

But she didn’t throw herself into the sport again until during the pandemic while living in the D.C. area — and she decided almost immediately to go not just big, but biggest.

“I don’t know, (the pandemic) clearly did crazy things to all of us, because I was like ... Why not? ... This is a super-hard thing to push myself towards,” Molly says of choosing the English Channel as her goal. “I think just having something so big to work on was almost mentally exactly what I needed at a time when everything felt like, Oh my God, the world’s on fire! ...

“Of having this one thing of like, Well, pool’s open. I’ll go try this.”

Her mom didn’t hesitate when Molly asked if she’d be her support swimmer: The answer was yes, absolutely. Kay did, however, have plenty of hesitations after that, as she learned more and more about Channel swims.

“I would wake up in the middle of the night going, OH MY GOSH! WHAT IS HAPPENING??,” Kay recalls. “For all of 2022, I was just scared. I was like, How is this gonna go?”

‘She trained harder than I did’

Since 1875, fewer than 1,900 people have successfully completed the English Channel swim.

It’s a rather messy comparison, but for what it’s worth, since Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay first reached the summit of Mount Everest in 1953, more than 6,000 people have done the same.

About one-third of those who set out to swim across the English Channel wind up quitting.

Under perfect conditions, you’re going to swim more than two dozen miles in near-hypothermia-inducing seas — and the conditions are rarely perfect. There’s always a chance of big swells and powerful winds.

You’re also at the mercy of when the captain gives the green light to go, which sometimes is in the middle of the night when you’d rather be sleeping. When you do swim at night, you see almost nothing but blackness. While swimming during the day, you’ll see some of the largest ships you’ve ever seen, since the Channel is one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world, and it doesn’t shut down for swimmers (although, interestingly, swimmers do have the right-of-way).

Oh, and then there’s the training.

Without getting into the gory details, let’s just leave it at this: Molly says her biggest training week saw her swim 60,000 yards (about 34 miles), including an eight-hour swim on Saturday and a five-hour swim on Sunday. In addition, to prepare for the cold water, she’d soak in ice baths for sometimes more than an hour; or she’d swim in the Chesapeake Bay deep into the fall, as its temperatures plunged into the 50s.

Kay, meanwhile, took her training just as seriously, swimming an estimated 800 miles in anticipation of being able to join Molly in the ocean for up to four one-hour periods. (It might seem like an arbitrary amount of time, but the intent of the rule is basically to not give the person attempting the Channel crossing too much help.)

“(It) feels like a crazy thing to say, but I think she trained harder than I did,” says Molly, who works as a public health analyst in Maryland. Then Molly quickly adds: “Though it’s not really fair to compare ourselves to Kay, I think, when it comes to exercise.”

They even got to train some together; Molly would sneak down to the Charlotte area when she could to do training swims with her mom on Lake Davidson. They also went to Maine earlier this summer to find some colder bodies of water, away from the steamy lakes and rivers in Charlotte and near D.C.

Over time, Kay became more excited than scared. But then this past June, less than two months before Molly’s attempt, she read about a man who went missing during an attempted Channel crossing and was found dead in July in waters near Belgium.

“I’m like, How do you lose a swimmer?,” Kay says. “That had never dawned on me, that somebody could die doing this.”

Sand through the water beneath her

But last Wednesday, the captain gave Kay the OK to hop in the water next to Molly (who had been running Taylor Swift’s “Daylight” in her head on a loop since the sun appeared), and a rush of excitement hit her like a tidal wave.

“When I got in on that first one I’m like, I am in the English Channel!,” Kay recalls. “Molly’s, like, dying, and I’m like, YES! I’m here! ...

“It was pretty amazing.”

To a certain extent, Kay is right. Molly was dying — in the sense that she was miserably cold, miserable physically. She’d flirted with hypothermia the previous night. (Wetsuits are considered an aid and are not allowed; swimmers attempting a crossing can only wear a swimsuit, goggles, a swim cap, a nose clip, and ear plugs.) She’d swallowed enough salt water in the rough conditions that it caused her to throw up multiple times. She’d also been stung by jellyfish, repeatedly.

At the same time, she was feeling as alive as she ever has.

“I’ve had major depressive disorder since I was 18, and I’ve had a couple of depressive episodes that have been really rough, spiritually very low, really hard to find joy in anything,” Molly says. “But swimming has always brought me such peace. ... I feel very grounded in my body (when I’m swimming). ...

“So when I was doing the Channel and I was like, This is f------ hard and I want to quit, I kept trying to visualize me as a very tiny dot in the ocean ... thinking about how all these bodies of water are connected.”

In the midst of the physical and mental pain she was battling, Molly found some semblance of peace thanks to that thought, and thanks to her mom’s presence, and to the sunshine, and the moments when she’d look back and see the Cliffs of Dover. There were still several more times when she wanted to quit, especially when she hit a portion of the Channel near France where, she says, “that current was insane ... and I, for a full hour, was giving it my absolute all.”

After nearly 14-1/2 hours and roughly 36 miles of swimming, maybe 200 yards from the French shoreline, Molly could see the sand through the water beneath her. Moments later, she became the 1,864th swimmer to achieve the crossing.

She ambled onto the beach and raised her arms triumphantly as members of her support crew (including her dad, Tim, her wife, Megan, and her friend, Tara Mount) cheered from the boat, with lumps in throats and tears on cheeks.

Kay, fittingly, was the first to give Molly a hug — one Tim describes as “an embrace like no other.”