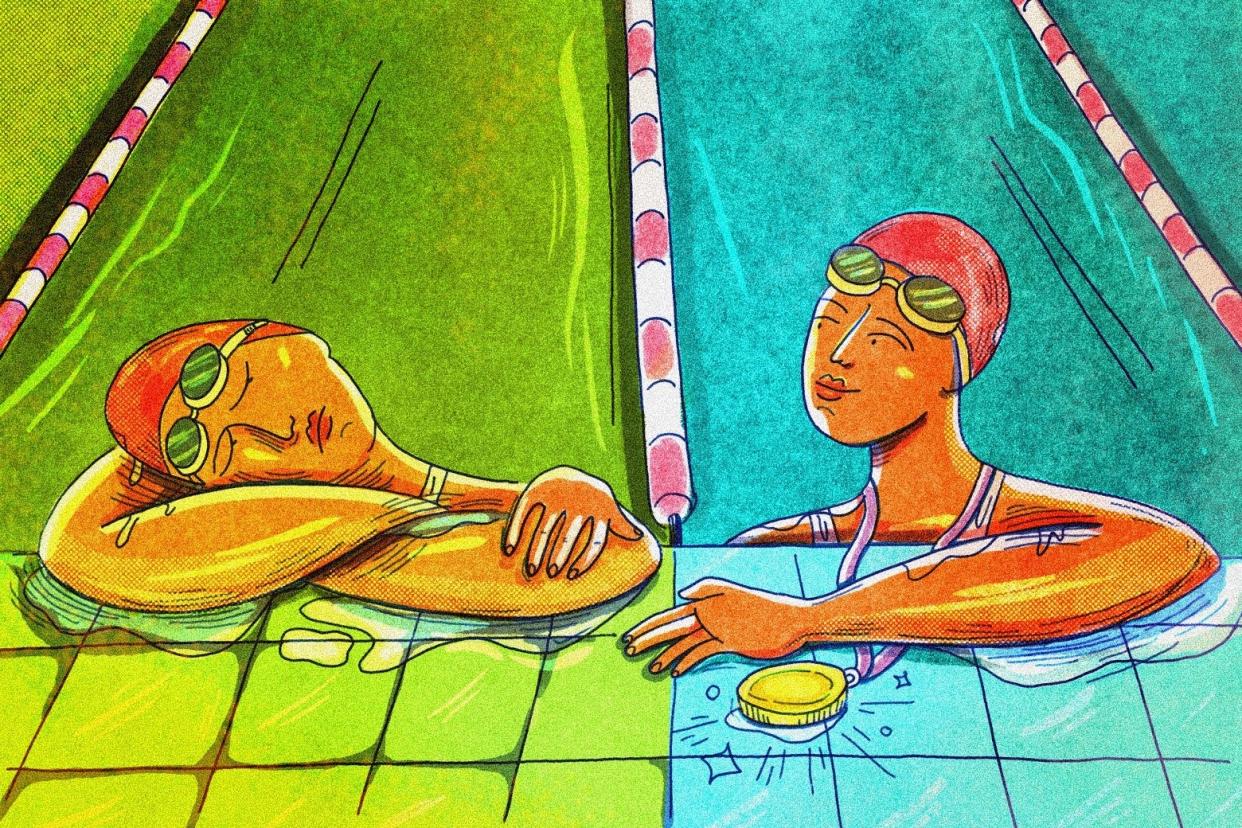

She Wanted to Swim at the Olympics. Would a Chronic Illness Make That Impossible?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This is an installment of Good Fit, a column about exercise.

When Kathleen Baker was 13, she Googled “Olympic swimmers with Crohn’s disease” and came up short. There wasn’t anyone—no one for her to read about or model her path after. She wondered if her dreams were over.

Crohn’s disease, which causes inflammation in the digestive tract and can lead to extreme stomach pain, left Baker exhausted. She would find herself too fatigued to finish a swim practice—even having broken state records just months before. How could she ever make it to the Olympics with a chronic illness weighing her down?

Baker did become an Olympian, winning gold and silver medals at the 2016 Rio Olympics, and it would be tempting to wrap her story up neatly in that bow. But the truth about the path she took to her dreams is that it was littered with blood tests and fatigue and immunocompromising drugs that managed the Crohn’s but left her vulnerable to other illnesses. There was a broken rib from low bone density. There was the time she was in the hospital for two weeks, sick with pneumonia.

There was the mental burden of not only wanting to be the best in the world, but wanting to be the best in the world while knowing that she will be some level of sick forever. Like many chronic illnesses, Crohn’s can be kept at bay with regular infusions of medication, but it cannot be cured.

Society tells us that much of our worth is tied up in our bodies—in what they look like, what physical feats they can perform, and how far we can push them. But chronic illness forces you to make a choice: look at your body differently, as something that is imperfect, or spend your entire life mourning what has been left behind in the land of health. For chronically ill athletes, it can be a tightrope walk to figure out how to push their bodies while respecting the limits of their diseases.

The logic of athletics can be straightforward. The thinking goes, “If I train more, I’ll be faster, I’ll be better, I’ll win more medals,” Baker says. But her condition complicates it. “To have a chronic disease that literally prevents me from doing that was really hard for me to conceptualize as a teenager.”

When she was first diagnosed, Baker had difficulty reading her body’s cues for when she was approaching her limits. “As I’ve gotten older, I’ve been able to read my body a little better,” she says. “Like, ‘Hey, today, I’m going to be able to push myself to the end-all brink of my physical effort and be OK.’ And then there’s some days where I’m already not feeling well and if I push myself to the end, it’s not going to benefit me.” Instead, she could find herself in what people in the chronic illness community call a “flare,” which is when symptoms worsen. With Crohn’s disease, flares can manifest through diarrhea, fever, heightened fatigue, and weight loss. When Baker feels a flare coming, having an open conversation with her coach about her limits helps. She may swim aerobically during practice instead of racing, as a way of balancing the need to go easy with a desire to train.

Finding that balance is not always possible. She has had to miss meets due to flares or complications, and managing her Crohn’s-related fatigue remains a struggle. But there’s something else, too. “I have a lot more joy in my sport than most people do,” she says, “because I feel like I could lose it.”

A chronic illness diagnosis is daunting to anyone, but can feel particularly disheartening to athletes. Amy Yates, 24, played competitive softball from childhood to her teenage years, and she had internalized the messages she’d heard about what it meant to be successful in sports. “I was always taught to push myself to my limits,” Yates says. “Now, pushing myself to my limits results in a few days of pain and not being able to function.” Her chronic illness—which she’s still searching for a diagnosis for—surfaced when she was 19. Since then, she’s struggled with joint pain and fatigue.

She’s found that yoga, swimming, and walking her dog allow her to move her body without aggravating her symptoms. But sometimes even the thought of walking is too much. Chronic illness makes her feel both more in tune with her body than ever—focused on what it needs and how it’s feeling—and trapped by it. “There’s the balance of … how far can I go before I’m crashing?” Yates says. “What are my tells? How can I pick up on the flags my body is giving off and how can I accommodate for that?” On bad days, she feels defeated by her limits. And on other days, she says she uses the athlete mentality to push forward through her new reality—even if the new reality is that her exercise for the day is walking her dog around the block.

Recalibrating what counts as success as an athlete is important. “I really practice being proud of just getting moving in general, even if that’s a walk or dancing in my chair,” says Ali DiGiacomo, who maintains Instagram and TikTok accounts dedicated to her life with rheumatoid arthritis.

Exercise can sometimes actually help with the symptoms of chronic illness. DiGiacomo was diagnosed at 15 years old, and even though she was a competitive swimmer before she got sick, it would take until she was 25 for her to return to movement. “In the chronic illness world, we tend to mourn our past selves,” she says. She started working out again as an outlet for anxiety and almost immediately felt less stiffness in her joints, a symptom of RA. DiGiacomo shared her journey back to fitness online and eventually even became a certified personal trainer, urging her clients and followers to do what they can and helping them modify workouts to suit their needs. Our bodies are “thankful when we move, even if it’s minimal,” she says.

For Jordan Wheatley, 32, those modifications take place in pole dancing classes. Wheatley has Ehlers-Danlos, a connective tissue disorder, and has found that the pole dancing community is understanding of physical differences, with instructors helping her modify her grip on the pole based on her abilities and how she’s feeling. “One thing that’s really common is instructors going around the room and asking for injuries, which is kind of comical because whenever it gets to me, my canned response is ‘I’m always injured—I’ll let you know if anything that you’re teaching is going to be a problem.’ ”

Wheatley posts videos of herself pole dancing, and she’s not worried about the judgment that may come with her chosen form of exercise. She knows what you’re thinking, but she also knows what’s true: Pole dancing has let her reconnect with her own body, chronic illness and all.