Sheboygan County students may not be learning all they could about Wisconsin's Native peoples

SHEBOYGAN COUNTY — Jeff Ryan remembers going to the boat landing protests for Indigenous fishing rights. He grew up near the St. Croix Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin reservation in Frederic, a village of roughly 1,100 people in northwest Wisconsin.

“Not because I was any type of an activist or anything,” Ryan said. “I went to the landings because the people that were being targeted — the verbal abuse, the rocks, the racial slurs and epithets — these were people that I knew.

“These were friends of mine, and I knew that (you) just don't treat people that way,” he continued.

Chippewa, also called Ojibwe, tribal members were fighting for their right to hunt, fish and gather on their lands, an issue that arose more than 100 years after land was ceded to the federal government in 19th century treaties. The treaties stipulated the tribes still had rights to use the land. Attempts to restrict and regain tribal access came in following years, culminating at a point with the 1983 Voight decision, ruling that Ojibwe members could hunt and fish on and off reservation land.

Conflict emerged in the late 1980s and early 1990s, known as the Walleye Wars, between tribal members and sports fishermen, who were against them fishing walleyes during spawning and harvesting seasons in off-reservation areas.

Among resolutions during that time, a law passed mandating Native American history, culture and tribal sovereignty be taught in Wisconsin schools.

Ryan, now a 35-year tenured teacher, has informed this curriculum for First Nations and U.S. history courses at Prescott High School, about 80 miles south of where he grew up, with his own experiences. He follows the standards, but also creates immersive learning experiences for students, a possibility realized after building trust and relationships with Native nations.

“We need to know something about our neighbors,” he said. “That's what I believe is incumbent upon me as a public school teacher — that we know something about our Native neighbors. They were here first. They were here long before we were.”

Ryan’s approach is not the norm among many educators, though.

Wisconsin state law requires public schools teach about Native American history and culture, but with locally controlled school districts that determine and enforce much of the curriculum, the learning experience and information shared can be very different. That’s seen across Sheboygan County schools, too.

Native American curriculum takes different shape across Sheboygan County schools. Some don't seem to comply with Act 31.

Some local school districts center Indigenous curriculum around colonization, early interactions with Europeans and comparison with Indigenous peoples from New Zealand or ancient civilizations. Others focus on Wisconsin nations, as required by the statute, and adopt resources from Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction or connect with Native nations.

Several state statutes, commonly known as Act 31, require public schools and aspiring teachers to incorporate and learn curriculum related to the history, culture and tribal sovereignty of the state’s 11 federally recognized Native nations and communities. This includes creating a curriculum for elementary to high school students related to Chippewa land rights and sovereignty, taught at least twice in K-8 and once at high school grades.

These statutes, if followed, equip students with disparate understandings of Indigenous people in the area. And for some, it may be their only opportunity to learn about Native communities, and neighbors, in their state.

4K through third-grade students at Cedar Grove-Belgium Elementary School learn about Native issues in conjunction with Thanksgiving and holidays during informal discussions in social studies, according to Principal Jeff Kondrakiewicz. Fourth-graders learn about Wisconsin history and interactions between Native peoples and explorers.

Kondrakiewicz said this content and level of depth is “developmentally appropriate.”

When students reach the high school level, Cedar Grove-Belgium High School Principal Josh Ketterhagen said they’re exposed to Native topics in U.S. history and English courses. He said students learn about the boarding schools in Wisconsin and read Native literature, like creation stories “The World on the Turtle’s Back” and “The Sky Tree.”

Beyond the Act 31 mandate set at the school district level, Ketterhagen said curriculum is fleshed out per building.

“Law says that everyone has to be able to at least be exposed to it,” Ketterhagen said. “We want to make sure that all of our students have it.”

Oostburg School District's incorporation of Act 31 standards looks different. With emphasis on fourth, seventh and high school grades, students learn about Native peoples in relation to broad geographical regions, manifest destiny and Wisconsin's tribal nations' historical connection to the present day, according to Superintendent Kevin Bruggink.

At Random Lake, it’s applied to each grade level’s “power standards,” or high-priority learning goals, through social studies courses. This includes learning about the state’s Native nations via broad topics of geography, history and the economy and more specific areas like treaty rights and western settlement, former elementary school principal Sandra Mountain told the Sheboygan Press last year.

Mountain said teachers access primary sources and teaching ideas from the Wisconsin First Nations educational resources.

Students at Sheboygan Area School District schools learn about Native peoples largely from a historical lens, relating to Columbus Day/Indigenous Peoples' Day, early exploration, colonization and ancient civilizations, Jim Renzelmann, SASD coordinator of instructional services, said.

“We have the observance, but we don't do anything district wide,” Renzelmann said about Columbus Day/Indigenous Peoples' Day. "We don't have any special thematic pieces, unless it's somewhere where it falls into the curriculum scope and sequence.”

Renzelmann did not provide specific examples of how Act 31 topics are incorporated at varying grade levels.

Learning about Native nations is different at the School District of Sheboygan Falls, too. Mark Thompson, high school social studies teacher, said third-grade students get a “snapshot” of tribal cultures in the state and fourth-grade students could learn about treaty rights in Wisconsin. Fifth-graders also learn about treaty-making and the impact of Native peoples on the state.

Thompson said the school reached out to the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin a few years ago to get information when its curriculum was being developed.

"Sometimes we get trapped within our own perspectives and the perspectives of the materials that we've been asked to teach," Thompson said. "Sometimes you need to explore other perspectives to get the whole story or to kind of enrich the students' understanding of culture and history."

Learning could call for unlearning what has been taught about Native peoples.

J.P. Leary, a member of the Cherokee/Delaware tribe, was once asked the name of his horse and if he used shields while visiting an elementary class in southcentral Wisconsin. He has neither. Leary was also shown model teepees and wigwams.

“I thought, yeah, these are cool. You know, these kids have some modeling skills,” Leary said. “But it was sort of this disconnected, historical architecture kind of lesson, it wasn't really anything about Native people in the area.”

He said the questions were problematic. It was like “I should have stepped out of the 19th century into their classroom,” he said.

Leary, an associate professor in First Nations Studies, History, and Humanities, faculty affiliate with the Education Center for First Nations Studies at University of Wisconsin-Green Bay and author of “The Story of Act 31: How Native History Came to Wisconsin Classrooms,” said there’s a lot of “rebalancing” and filling in former knowledge with Native perspectives in his classes.

“Even where you may have learned legitimate things, how often have you heard those things from a Native perspective?” he said.

“We're not saying, ‘Well, you learned that from a non-Native person. That's no good.' Right?” he continued. “We're saying that these are a range of voices that you haven't heard. There's no need to stigmatize these voices over here, but they've had a lot of attention, right? We're going to have these insider voices and provide that opportunity to learn from them.”

Some students in Leary’s classes are being exposed to primary sources or Native stories years since grade school or for the first time.

“I think about generations of adults walking around with a fourth-grade understanding of Native issues. I like to think that we are developmentally more complex creatures than we were at 9 and 10 years old,” Leary said.

Going to the source of information has been key for Ryan’s courses at Prescott High School.

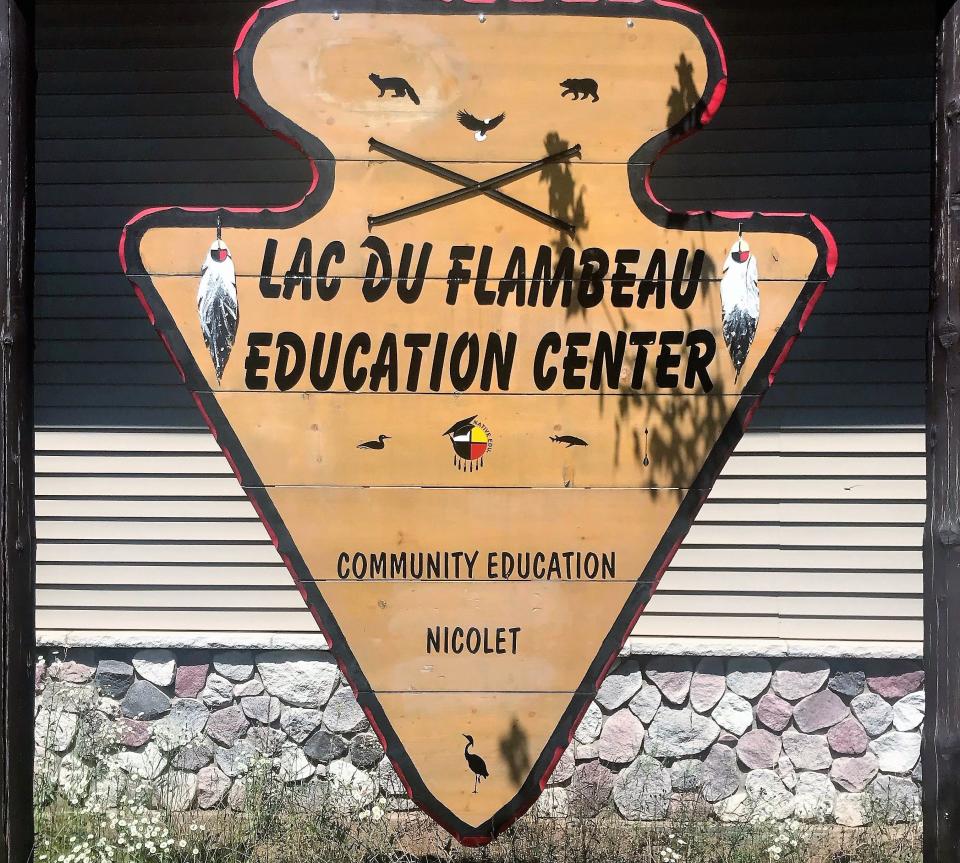

In addition to teaching about the different Native nations in Wisconsin, Ryan has developed relationships with tribal members to host community discussions and take students to visit the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians. He said more than 400 students have gone over the years, 250 miles from their community.

A group of students who went with Ryan this year shared they learned about cultural, community and governance differences. They had group discussions and witnessed drum circles at the reservation, as well as grew their understanding of burial practices and boarding schools.

"I think it's important to understand them (Indigenous people) and not to repeat history and not have things like the Walleye Wars happen again," Allie Tibayan, a sophomore in Ryan's AP U.S. History, said. "Hearing people's stories from when that was happening was insane to the point where I had goosebumps all over my body just listening."

Other students also shared they learned more about cultural preservation efforts, generational poverty and Native pride. For many, there was a sense of respect and tolerance.

“We can provide instruction and follow the letter of the law while completely missing the point of all why it exists," Leary said.

What to know about Hmong New Year: Sheboygan Hmong New Year returns. Here's what to know about this year's event.

Native peoples live in Wisconsin today. But they're not largely represented in local curriculum.

A lot of Sheboygan County staff shared their focuses on Native issues were largely from a historical lens. Some did not focus specifically on Wisconsin nations' history or contemporary issues.

David J. O’Connor, a member of the Bad River Band at Lake Superior Chippewa and American Indian Studies Consultant for Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, said preserving local histories is important, but there needs to be a balance.

“If you don't talk about the voice, the communities, the people today, that's a big piece missing,” he said.

Ryan said he brings in contemporary topics like Native American logos, tribal membership, gaming issues, land acknowledgments and ongoing sovereignty struggles.

Individuals who identify as Native American live in Wisconsin today. According to available 2020 U.S. Census data, 2.5% of the state population, or 144,572 people, identified as being Native American and/or Native Alaskan.

Native communities in the state are contributing to climate change mitigation, voter turnout, and the state economy through sectors like agriculture and gaming.

Ongoing Native issues in Wisconsin also include battling an oil pipeline on Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa land, land stewardship and protecting the environment and language preservation.

“Native people are not stuck in a time capsule,” Ryan said.

Ensuring schools are compliant with Act 31 statutes is largely the responsibility of the school boards, with little, feasible enforcement power from the state. Leary said there is an enforcement provision, but it'd result in withholding 25% in state aid.

"It's as if the only response in a military conflict is to use nukes," Leary said. "Nobody's going to do that."

Implementing Act 31 statutes could be challenging with resources, support. The state has a variety of resources to help.

Many Sheboygan County district staff said Act 31 was important for various reasons — exposure to different cultures, application of learning skills, opportunity to examine accuracy of historical narratives, passion for diversity and inclusion, and efforts for tolerance. At the same time, they shared there could be barriers to implementing it, like instructors’ bandwidth and curriculum support.

“The primary challenge with any specific curricular area comes with the broad number of standards public schools are required to address,” Bruggink, of Oostburg, said. “We work to weave specific areas of focus into more general curricular areas like reading and writing. That is a large part of our approach to learning about Indigenous cultures.”

The goal could be simply complying with Act 31 while working for adherence to various standards.

“It's not something that I'm going to say that, ‘Yes, this is a deep focus,’ But we cover it,” Mountain said about Act 31 at Random Lake. "I do think our kids do leave here with a pretty well-rounded knowledge of, especially the historical perspective of the tribal nations of Wisconsin.”

Native youth treatment center pushback: Northern Wisconsin town official lists solar panels among reasons to oppose Native youth treatment center

School districts like Sheboygan Falls may have been able to make more headway because they have curriculum instructors, which not all districts have. Thompson worked closely with Becky Charbonneau, former universal design for learning coach, to assess their curriculum with the standards and resources.

“Not that we're perfect, but we have had the opportunity to do that,” he said.

Since Act 31 went into effect, there have been efforts to support educators with real-life implementation.

Through DPI, O’Connor works with educators and school districts across the state to include Native stories and histories. Training groups have grown from 10 to 70 people over the years, he said.

O'Connor said these opportunities could be essential for educators who are eager to learn and update their curriculum but may not know where to start. It could also call for finding materials through Wisconsin First Nations resource or unlearning and relearning.

He said sometimes he asks educators to name famous Indigenous people, and they always offer historical figures. There may also be misconceptions about Native peoples, like they only live on reservations.

"A large number of our Indigenous people don't live on our reservations. They live in urban areas, like Milwaukee,” O'Connor said. "Those are stories that need to be told to recognize that as Indigenous people, we've shaped Wisconsin from a historical lens, we shape Wisconsin today."

Other instructors may not have district or school board support to give Act 31 a deeper focus, unlike Ryan, who said he received support from the Prescott school board and three superintendents.

He said had to lead the efforts, though. It wasn’t easy. It took many years to build trust, develop relationships and create a way to talk about Native issues that may be deemed controversial, like treaty rights and casino operations, in a sensitive and appropriate way.

"Act 31 is more than just showing ‘Dances with Wolves’ in the classroom. It's more than that. It's a lot more than that,” he said. “And it's not easy to cover all those topics.”

Ryan’s initiative has been fueled by an eagerness to learn and listen, a willingness to ask for help and learn from and create partnerships with Native peoples. Tribal elders have told him how meaningful having students and him listen is to them.

He said, "That eagerness to learn — that's what I want to instill in kids."

Contact Alex Garner at 224-374-2332 or agarner@gannett.com. Follow her on X (formerly Twitter) at @alexx_garner.

This article originally appeared on Sheboygan Press: Sheboygan area schools: Act 31 and teaching about Native Americans