Shellys: Looking at 'necessary trouble' to find equality, justice for all

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Recently, Drew Gilpin Faust, Harvard University President Emerita, wrote a memoir titled, "Necessary Trouble, Growing Up at Mid-Century." She grew up in the 1950s in a conservative, white southern family in segregated Virginia. The norms of the day expected her to be a “well-adjusted” and “poised young lady,” which meant adopting a “willful blindness” to the inequalities and injustices of her day. Yet at age 8, she found her voice and wrote a page-long letter to President Eisenhower, asking him to end segregation. She found it necessary “for her survival” to become engaged, even at a young age, in a life-long journey as an activist and historian.

All of us who grew up in the middle of the last century have a story to tell of how we were or were not affected by what was happening in the United States. Whether we lived in the north or south, in rural or urban environments, change was occurring all around us. Our stories may reflect an insulation from unsettling events, or if we were kids growing up in minority communities, we most likely experienced the fallout of segregation on a daily basis.

Both Walt and I grew up in urban environments. Walt lived in an ethnically diverse neighborhood in Wilmington, Delaware, a racially segregated city. Yet as a young boy, he remembers Inez and James, a black couple, who worked in the apartment building next to his row house. He remembers his mother offering a black sanitation worker a cup of water on a hot summer day. Working a summer job in construction, Walt remembers offering a black coworker a cup of water, which he turned down, because he understood the unspoken rules. Although his school was segregated, Walt played church league basketball, which included an AME team. The rules behind segregation were always present.

My experience was different. I was insulated from contact or interaction outside of my own protected world. I went to parochial schools from first grade through high school, and lived in a neighborhood that reflected segregation, as did my church. Our small black and white tv was never tuned to anything implying a threatening, outside world. There were several isolated memories. During WWII, my Uncle Elmer brought me a black, rubber baby-doll; my mom and I followed my dad to Washington State, where he was stationed, and there, my best friend was Harvey, a little black boy my age. It wasn’t until high school that I had a black classmate and friend. Unlike Drew Faust, I did not make any “necessary trouble” and my interactions were very limited.

One college incident in Greeley, Colorado became a pivotal moment in my life. I chose Sociology as a major and one of my friends and classmates was a young, black man. One day in 1960, he was going to walk downtown and asked if I wanted to go. I said “yes,” because he was my friend and we had a lot to talk about. When I returned to my rooming house, the housemother took me aside and gave me a lecture about never doing that again.

Walt and I came to West Texas State University in the Fall of 1963 and the Civil Rights Movement compelled us to move from the sidelines to active engagement. TV transported us and our students to Selma and Montgomery, to Washington D.C. in 1963, to Dr. King’s assassination, and to burning cities. In 1968 on Easter Sunday there was an organized march following Dr. King’s death. The campus was not immune to racial unrest during the 1960s, as referenced in Dr. Marty Kuhlman’s book, "Always WT" (pp. 352-355). Racial tensions sometimes ran high and surfaced with housing issues, inter-racial dating, and disagreements over flying the confederate flag. Our classrooms were rich with questions, dialogue and critical-thinking. The 1964 Civil Rights Act, 1965 Voting Rights Act, 1968 Civil Rights Act were passed, as Walt taught his political science classes.

We were hopeful about the positive changes we witnessed during that time, yet today, we can easily become discouraged with ever present racial divisions. Today we witness the sanitation and erasure of racial history, restrictions on voting rights, and continuing unequal experiences in the legal, economic, and educational systems. Shame on us! An educated, knowledgeable citizenry, which experiences equality and the same justice, is a necessary foundation for a democratic society. It will become increasingly important that we engage in “necessary trouble” as we attempt to remedy our racial divisions. Now is not the time to insulate ourselves from the issues of our day.

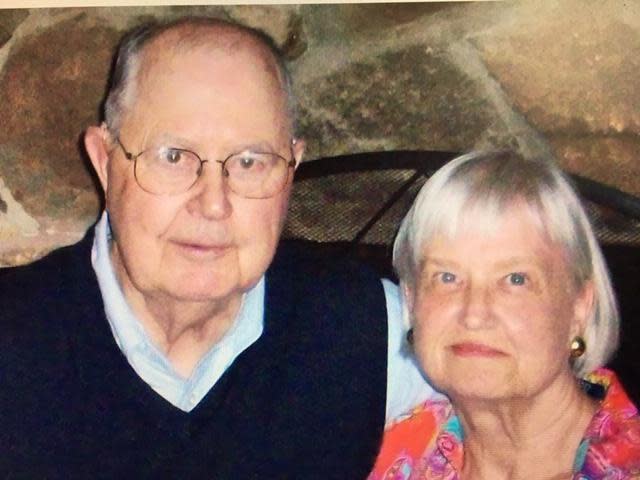

Walter Shelly retired after 40 years as a professor of political science at West Texas A&M University. Linda Shelly retired after 33 years of teaching sociology at West Texas A&M University and Amarillo College.

This article originally appeared on Amarillo Globe-News: Shellys commentary: 'Necessary trouble' key for remedy to divisions