‘Shockingly low’ bonds in child sex trafficking case put SC magistrates under microscope

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In a recent decision the local solicitor said shocked his conscience, an Orangeburg County magistrate without a law degree granted the pretrial release of a mother accused of trafficking her 7-year-old daughter to a 61-year-old man.

The woman was not required to post bond or prohibited from contacting the alleged victim. She was rearrested five days later after allegedly attempting to dissuade the girl from cooperating with police, and immediately bonded out on the new charges.

Around the same time, in a case that raises conflict-of-interest questions, a different Orangeburg County magistrate dismissed felony charges against a man accused of sending a sexually explicit video of himself to an underage girl. The man’s lawyer, who had a personal and professional relationship with the judge, claimed he hadn’t been provided evidence collected by the sheriff’s office. A sheriff’s sergeant denied her office had received the discovery request, but the judge did not give her the opportunity to testify.

These cases represent only a recent sampling of questionable judicial conduct in a single county, but they illustrate the outsized impact magistrates exert daily on consequential matters of public safety. For years, Gov. Henry McMaster and some state lawmakers have voiced support for increasing qualifications and enhancing screening requirements for the state’s more than 300 magistrate judges, most of whom lack law degrees or any significant legal training. But little has been done to meaningfully address concerns.

Several bills introduced this year would tweak the system on the margins, but none address issues raised by the recent Orangeburg cases, such as magistrate qualifications or legal training requirements. While one proposal would prohibit state senators, who appoint magistrates, from appearing as attorneys in their local magistrate courts, it does not deal with other potential conflicts of interest.

Potentially more impactful are a number of bond reform bills that would require judges to consider multiple factors when setting bond, including whether a defendant was out on bond for another offense when charged.

Magistrates, who set bonds for criminal defendants on all but a small subset of cases and conduct probable cause hearings for defendants facing serious criminal charges, are frequently criticized for their lenient treatment of violent and repeat offenders.

Granting bonds to such defendants, law enforcement officials argue, jeopardizes public safety and deters witnesses from cooperating with police.

“I love our magistrates. I teach them every year,” said Jim Huff, founding member of the South Carolina Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. “But I have many examples where they have been weak on bond hearings for people who are already out on bond.”

State Rep. Robby Robbins, a Dorchester Republican, was even more explicit in his critique of magistrates — also known as summary court judges — during a recent House Judiciary Committee panel on bond reform legislation.

“Summary court judges are not doing their job,” said Robbins, a former prosecutor and practicing criminal defense attorney. “They are not protecting the public by letting these people out on bond two and three and four and five times. That’s why we’re here.”

‘Shockingly low’ bond set for accused child sex trafficker

The bonds set recently for two Orangeburg County residents charged with sex trafficking a 7-year-old are the latest frustration for First Circuit Solicitor David Pascoe, whose jurisdiction covers Orangeburg, Calhoun and Dorchester counties.

Pascoe said he’s increasingly come to believe that circuit court judges, who must be licensed attorneys, should set bond in more serious cases. Currently, they do so only when a defendant’s charges carry a possible life sentence or when a defendant is charged with a violent crime while out on bond for a separate violent crime.

In the recent Orangeburg case, Magistrate Judge James Rickenbacker set the bonds on the defendants’ trafficking charges, which carry a 30-year maximum sentence.

He gave John Richard “Ricky” Williams a $5,000 surety bond – which Pascoe described as “shockingly low” – and let Alana Ann Westbury out without requiring her to put any money down or stipulating that she have no contact with the alleged victim.

Williams and Westbury, who both are married to other people, were arrested Jan. 7 following an investigation by the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division.

Prosecutors allege Westbury forced her 7-year-old daughter to engage in sexual activity with Williams on multiple occasions, beginning last summer.

“I believe the price was between $200 and $500,” SLED Special Agent Melissa Allen testified at Williams’ initial bond hearing.

Williams, the owner of a local auto repair shop, is charged with human trafficking and criminal sexual conduct with a minor under the age of 11, which carries a mandatory 25-year sentence with the possibility of life imprisonment.

Westbury, a stay-at-home mom, was initially charged with human trafficking and three counts of unlawfully placing a child at risk. The latter charges stem from the accusation that Westbury herself had sex with Williams for money while her two young children – the 7-year-old female victim and a 5-year-old boy – were in the home.

At the pair’s initial bond hearing, Rickenbacker, a non-lawyer with less than a year of experience on the bench, asked SLED agents for their bond recommendation, but did not heed it.

According to an audio recording of the proceedings, a SLED victims’ advocate asked Rickenbacker to give Westbury a surety bond and prohibit her from contacting her children until additional safety measures could be established.

He denied her request.

“I’m not going to take the rights away,” said Rickenbacker, who did not respond to The State newspaper’s multiple requests for comment on his decision.

Five days after Westbury’s release from jail, she was rearrested for allegedly attempting to intimidate her young daughter during a Department of Social Services-supervised visit.

According to an arrest warrant, Westbury “spoke with the minor victim and asked if the minor victim wanted to send the defendant, or the co-defendant, to jail in an attempt to obstruct or impede the administration of justice in her pending matter.”

A different Orangeburg magistrate gave Westbury a $75,000 surety bond on the witness intimidation charges. She posted it the next day and was released, according to court records.

Williams, on the other hand, has remained in custody since his arrest due to the prohibition on magistrates setting bond on charges that carry a possible life sentence.

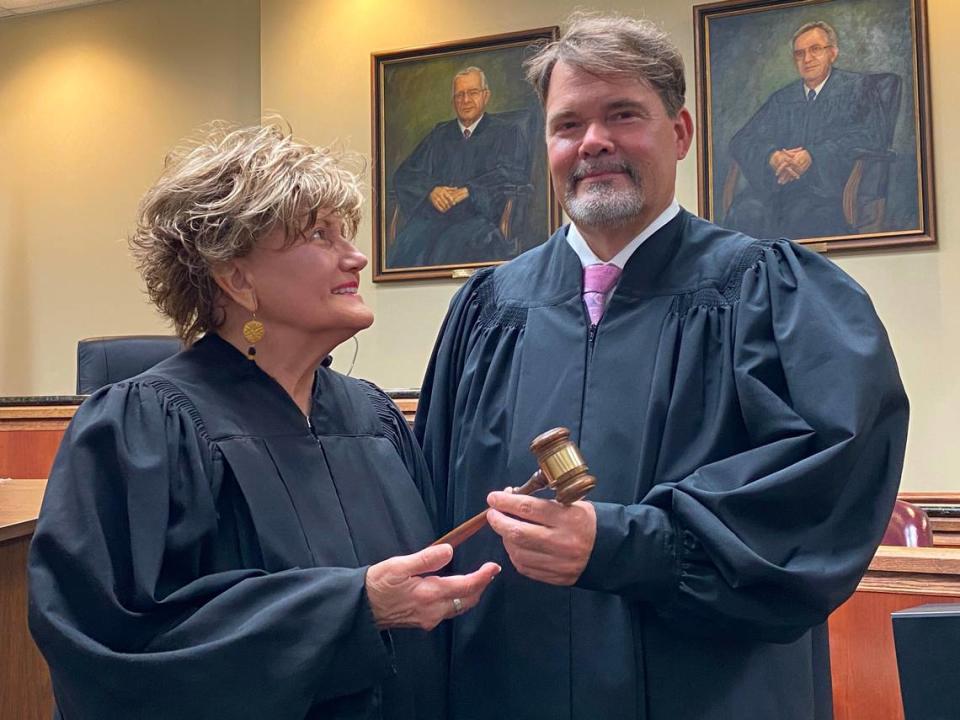

Circuit Court Judge Diane Goodstein last month denied Williams bond on his criminal sexual conduct charges and revoked Westbury’s bond at the request of prosecutors. As a result, both are likely to remain behind bars until their cases are resolved.

“Both Mr. Williams and Ms. Westbury are presumed innocent,” Pascoe said in a statement after the hearing. “However, given the severity of the alleged charges and the facts presented to the court today, we support Judge Goodstein’s decision to deny them bonds at this time.”

‘Bogus’ dismissal of child sex crime charges

Another troubling recent case involves an Orangeburg magistrate’s dismissal of charges against a St. Matthews man accused of sending an underage girl a video of himself masturbating.

Quentin Parker, 36, was charged last year with disseminating, procuring or promoting obscenity and criminal solicitation of a minor, felonies that carry maximum five- and 10-year prison sentences, respectively.

Orangeburg County Magistrate Judge Gary Doremus dismissed Parker’s charges at his Nov. 10 preliminary hearing after Parker’s attorney, Gerald Davis, claimed the sheriff’s office had not fulfilled his discovery request, a recording of the proceedings obtained by The State newspaper shows.

Orangeburg County Sheriff’s Sgt. Lakesha Gillard, who was on the stand preparing to testify at the time, told Doremus her office had not received the request and raised the possibility of delaying the hearing.

Doremus, a former associate at Davis’ law firm whose mother was once married to Davis, disregarded the prospect of continuing the case and simply dismissed the charges citing lack of probable cause.

His decision to toss the case due to an alleged discovery violation — an action generally reserved for a circuit court judge — struck legal experts as improper.

Former Circuit Court Judge Gary Clary, speaking generally, said it would be irresponsible for a magistrate to dismiss a felony case at preliminary hearing over an alleged discovery problem.

“The issue of discovery and so forth is something that should be reserved for a circuit judge,” said Clary, a former Republican state representative who spent 10 years on the bench prior to serving in the State House.

A magistrate’s role at a preliminary hearing, also called a probable cause hearing, is simply to determine whether sufficient evidence of a crime exists to warrant the defendant’s detention and trial.

The judge takes testimony from a witness – often the arresting police officer – and decides whether a reasonable person could be persuaded that the accused committed the crime. The defendant is not even allowed to offer evidence on his behalf, since the hearing is solely to determine whether the prosecution can show probable cause.

It’s uncommon for charges to be dismissed at this stage and discovery-related motions like Davis’, known as Rule 5 motions, are virtually unheard of.

John Crangle, a Greenville defense attorney and son of the well-known Columbia open government advocate of the same name, said in his 10 years practicing law he’d never heard of a discovery violation being handled at a preliminary hearing.

“If you can’t introduce any evidence, how do you prove you served the sheriff?” Crangle said.

In addition to ruling on something widely regarded as beyond his purview, Doremus also failed to publicly disclose his relationship with Davis, according to an audio recording of the hearing.

No explicit rule governs when judges should recuse themselves from cases due to conflicts of interest, but the Code of Judicial Conduct advises judges to “avoid all impropriety and appearance of impropriety.”

The Judicial Advisory Committee, which judges may contact for advice when faced with an ethical quandary, opined last year that judges should disqualify themselves from proceedings in which uncles or cousins – “a person with the third degree of relationship to the judge” – serve as lawyers.

While the committee has found that judges need not recuse themselves from matters involving their former law firm, as long as the case doesn’t predate their departure from the firm and they no longer receive fees for legal services performed on the case, Clary said he always disclosed such relationships to all parties at the outset of a case.

“I would immediately reveal if (former law colleagues) were involved in a case with the opposing side. I’d say listen, if you want me to recuse myself I will,” he said. “I just think that to maintain the integrity of our system, that was something I was always mindful of and never wanted to create any appearance of impropriety.”

Doremus, whom court records show has set bond in other cases involving Davis, did not respond to multiple requests for comment on his decision to dismiss Parker’s charges. It is unknown if the two men’s previous relationship was disclosed during those cases.

As a result of the dismissal, prosecutors were forced to present the case to a grand jury, which on Jan. 11 indicted Parker, trumping the magistrate’s actions.

Circuit Court Judge Maite Murphy set Parker’s new bond at $150,000, and as of Wednesday, he had not posted it, court records show. Parker is prohibited from having contact with the alleged victim, her family or any minor children, per Murphy’s order.

“When a magistrate dismisses a case on bogus procedural grounds, we’re always going to take a good look at it to see if it can be remedied in circuit court,” Pascoe said. “Failure to provide discovery is not grounds for a dismissal at a preliminary hearing, especially in a case that was only weeks old at the time.”

To this day, the Orangeburg County Sheriff’s Office has not received the evidence request Davis claimed he sent.

Prosecutors and other legal experts said the request shouldn’t even have been sent to the sheriff’s office.

According to the rules of criminal procedure, discovery requests should be filed with the prosecution.

While discovery for minor offenses, such as speeding tickets, may be sought from local police agencies, discovery requests in felony cases should always be sent to the solicitor, legal experts said.

“No criminal defense attorney in the state that I know of doesn’t serve it on the solicitor’s office,” Crangle said. “You have to. They’re the prosecution.”

Records show Davis, who declined comment on the case, didn’t request evidence from the solicitor’s office until nearly two months after Doremus dismissed the charges against his client.

Pascoe, who has advised the Orangeburg County Sheriff’s Office to document its myriad issues with local magistrates, said his office is now looking into other judicial decisions officers have flagged as improper.

“The Orangeburg Sheriff’s Office brought (the Parker case) to us within minutes of it happening after the prelim, and they’ve been coming to us often ever since,” he said.

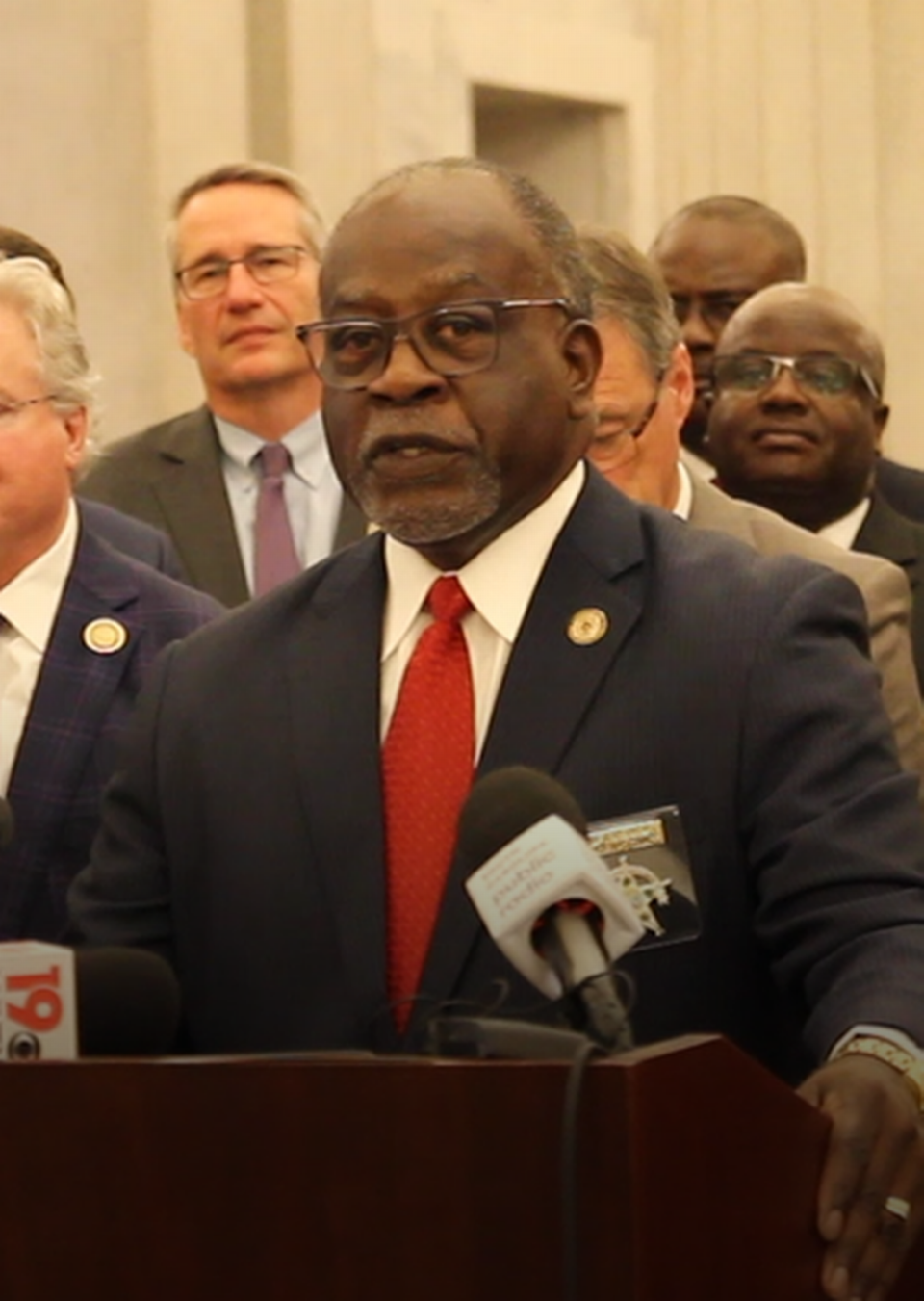

Orangeburg County Sheriff Leroy Ravenell confirmed he’d been working with the solicitor’s office out of concern for public safety, but declined to comment on any specific case or magistrate ruling.

“If these criminals continue to be released on little or no bond, we’re going to continue our efforts to make certain that justice is done,” he said in a statement. “We’re not in the business of catch and release so criminals can terrorize someone again. These low or no bonds are not helping the community.”

Need for reform

With the defendants in both recent Orangeburg County cases now behind bars, the potential for further harm to the public or the alleged victims is largely allayed.

That’s not always the outcome when magistrates make questionable rulings.

Many law enforcement officials can effortlessly rattle off examples in which criminal defendants released on nominal bonds reoffend, sometimes with disastrous consequences.

An oft-cited cautionary tale relayed at multiple recent legislative hearings involves a 42-year-old Clarks Hill man with 16 prior criminal convictions who in December 2021, while free on bond, allegedly initiated a wild shootout in downtown North Augusta that injured a police officer.

A bystander video of the incident shows the man exit his truck in the middle of a busy street, crouch behind the vehicle and fire off dozens of rounds at officers in broad daylight.

The man, who was facing numerous drug and weapons charges at the time, eventually surrendered and was taken into custody.

“That is a story that’s emblematic to what’s happening across the state,” said Jarrod Bruder, executive director of the South Carolina Sheriffs’ Association. “We’re seeing more and more violent individuals getting out on bond that are reoffending.”

Part of the solution, as Dorchester Rep. Robbins sees it, involves requiring circuit court judges to set bond for defendants accused of violent crimes.

“If we’re going to be trying to put these violent people in prison, I want them to go before circuit court judges,” he said at a recent legislative hearing. “We cannot have them continuing to go before magistrates or municipal judges on these offenses.”

Pascoe said that while he’s supportive of circuit court judges setting bonds in more cases, he thinks the root of the problem is the state’s judicial selection process.

South Carolina is one of two states in the country where the General Assembly – roughly a third of whom are practicing lawyers – picks judges.

Critics of the process say it breeds cronyism and makes judges beholden to state lawmakers, some of whom will inevitably appear before them in the courtroom.

Unlike many judges, who are screened by the Judicial Merit Selection Commission and voted on by the General Assembly, magistrates are hand-picked by local senators without the same level of vetting.

“We need to change the way we select all of our judges in this state, and that goes for magistrates as well,” Pascoe said.

Senate Minority Leader Brad Hutto, the Orangeburg Democrat who appointed both Doremus and Rickenbacker, said he doesn’t have a problem with the current system but is open to ceding the responsibility of magistrate appointment, as long as judges are not popularly elected.

“It doesn’t matter to me, in a way,” said Hutto, a lawyer for more than 40 years whose firm represents criminal defendants in Orangeburg County Magistrate Court. “Somebody’s got to make the appointments.”

Hutto said he takes his magistrate appointment powers seriously. Before selecting a new judge, he reviews the resumes of all prospective magistrates, speaks with people who know them and interviews each candidate to assess for temperament and intellect.

He said he does not expect preferential treatment from the magistrates he appoints and thus does not consider it a conflict that he may one day appear before them.

“One of the questions I always ask judges before I appoint them is: If you hear the evidence and I’m the lawyer and I’m not winning, you’ll rule against me, right?” Hutto said.

Most magistrates do an exemplary job, he said, and they’re generally of higher quality today than they were when he first took office nearly three decades ago. Ideally, all magistrates would have law degrees – a 2019 Charleston Post and Courier investigation found nearly three-quarters don’t have formal legal training – but it’s simply not feasible, Hutto said.

“In more rural counties, it’s virtually impossible to find attorneys,” he said. “In fact, it’s oftentimes hard to find anybody because the salary is just not there to attract people that we really need.”

Magistrate salaries vary widely by county, ranging from $10,000 in rural Lee County to $115,000 in Spartanburg County, according to a 2022 Wage and Salary Report commissioned by the South Carolina Association of Counties. Orangeburg County magistrates make between $80,000 and $90,000, according to the report.

The Orangeburg senator declined to weigh in on the recent decisions made by his local magistrates, saying it was not his place to get involved in individual cases.

He said if a magistrate consistently makes bad decisions and becomes the subject of numerous complaints he’d eventually hear about it, and, if need be, find a replacement.

“I don’t think senators should retain any review process,” Hutto said. “Once we appoint them, they’re on their own.”