Shooters getting younger: Record number of juveniles charged with gun-related murder

On an early June evening last year, three 15-year-old boys exchanged laughing emojis while they texted about a gun deal.

By the end of the night, a young man and one of the trio would be dead, shot in the head.

The deal went down after dark at a park in the Albany Crossing neighborhood on the city's Northeast Side. Two 18-year-olds walked up to meet the three teens, the young adults believing they would be trading a Ruger handgun and $300 for a Glock handgun from the teens.

Under Fire: An examination of gun violence around Columbus

But hours before, the younger trio planned instead to rob the older pair at gunpoint, or “get the cheese,” according to their text messages.

Terrell Hicks-Freeman texted, “Then soon as he hands me that money ky cock your gun,” referring to Makhy Andrews as “ky.” Baron Anderson was also in the chat.

Today, Terrell and Baron are charged with two murders, accused of getting their friend Makhy killed and of both shooting Layton Ridgedell on June 3, 2022.

The two defendants are among a record number of juveniles charged with murder in Franklin County over at least the last decade, almost entirely for shootings.

In 2022, 25 teens were charged with committing murder or aggravated murder that year or late the year before in Franklin County Juvenile Court. So far this year, 20 juveniles have been charged with murder or aggravated murder.

It’s a dramatic spike after a decade of mostly single-digit murder cases in juvenile court each year.

The rise aligns with a similar increase in the number of adults charged with murders, but the surge of younger defendants — which includes shooters as young as 13 or 14 — and their often-young victims has many in Columbus and nationwide concerned.

The answers to why this is happening are complicated. Defense attorneys, prosecutors, researchers and community leaders point to readily available guns, families struggling after the pandemic, kids’ exposure to violence, a mental health crisis among youth, and a culture on social media that both idolizes guns and quickly changes petty feuds from verbal disagreements to gunfire.

As Franklin County prosecutors say they’re seeing more and younger youths committing gun crimes, experts say the time to intervene is now, before communities are even more devastated by the consequences of kids having guns.

In August, for example, Columbus police arrested two 13-year-old boys — whom The Dispatch are not identifying — in the shooting death of 15-year-old Ra’Shawyn Carter at Easton Town Center on the Northeast Side. One is charged with murder and the other with obstruction of justice for allegedly giving false statements to police.

At the most recent hearing in the accused shooter's case, prosecutors and the teen's attorney argued over whether he is competent to stand trial, meaning he understands the charges against him. It's a common question in juvenile court due to the age of defendants. A judge will decide after another psychological evaluation is completed.

Over the past two years, one other 13-year-old has been charged with murder and two 14-year-olds have been accused in deadly shootings in Franklin County. Two of the three cases are still pending.

One, that of Marquel King, was resolved when he was sentenced in June to four years in juvenile prison after he pleaded guilty to involuntary manslaughter. Marquel was 14 when prosecutors say he and three friends robbed 18-year-old Thomas Hritzo III. Brent Boggs, then 14, fatally shot Hritzo, prosecutors say. Brent is facing trial in adult court.

Intervention in juvenile gun violence needed now

The national “epidemic” of gun violence among teens won't stop or get better without intervention, and it should be done now, said Rebeccah Sokol, a faculty member at the University of Michigan’s Institute of Firearm Injury Prevention.

Firearms are the leading cause of death among children and teens in the United States, according to the institute, with more than 4,700 people ages 19 years old and younger dying as the result of guns in 2021.

Exposure to violence — whether it involves a gun or not — increased a youth's risk of committing violence themselves by three to four times, according to Sokol’s research. That violence could be observed in their communities, their homes or their schools.

“We really need to work on the front end to kind of address why are youth feeling this need to carry a firearm and what can we do to stop it?” Sokol said. “We absolutely need to intervene, and we need to intervene now.”

It’s too easy to get a gun

Overall, juvenile crime has been decreasing for decades nationally, and the number of teens convicted of a felony is down across Ohio.

In 2012, there were 4,636 Ohio children convicted of felonies in juvenile courts, compared to 3,182 convictions in 2022.

In Franklin County, the numbers have also decreased slightly: 494 convictions in 2013 and 404 convictions in 2022.

But there are some alarming exceptions: juvenile charges for gun-related crimes like carrying a concealed weapon are creeping up. Over the past 10 years, the number of juveniles in Franklin County charged with carrying a concealed weapon has steadily increased, from 37 in 2013 to 99 in 2022 — and at least 81 through Sept. 15 this year, according to Franklin County Juvenile Court.

And car thefts have exploded, in a trend prosecutors say is related as some kids steal cars to find guns. Teens were charged in juvenile court last year with 571 cases of receiving stolen property (how authorities charge car thefts). In 2019, there were 229 such cases.

Many experts and community leaders point to the proliferation of guns overall — with more than 430 million owned by civilians in the United States in 2020 — as a cause for the rise in gun-related crimes among young people.

In 1997, less than half of that, nearly 200 million guns, were privately owned, according to a U.S. Department of Justice report.

“I definitely feel that it’s too easy for a juvenile to get ahold of guns,” said Anthony Pierson, deputy chief counsel for the Juvenile Division of the Franklin County Prosecutor’s Office.

In August, Madison Township police caught three teens at a Canal Winchester-Groveport Madison high school football game carrying Glock 9 mm handguns modified with Glock switches, small devices that turn semiautomatic guns into fully automatic weapons.

Social media can desensitize teens to the danger of guns

Being exposed to violence and seeing peers and others with guns frequently on social media can desensitize youth to the danger of weapons, said Kamilah J. Twymon, vice president of community based and education services at Buckeye Ranch, a nonprofit that provides mental health services for children and families.

“They’re not understanding how that decision of even carrying a gun can have a domino effect,” she said.

Not all adolescents understand the damage guns can do, and how dangerous they are, Twymon said, in part because guns become normalized and lose some of the threat of danger when teens see them so much on social media and in popular culture.

Kids are posing with guns, rapping about guns and violence, and even filming themselves using guns, according to prosecutors and defense attorneys. Thomas Gjostein, a Columbus defense attorney who represents more than a dozen juveniles currently charged with murder, said many of his cases include social media posts as evidence.

Seeing their peers with guns via social media can drive kids to think they need one themselves — for popularity and for protection, Pierson said.

“If you’ve got your face in your phone all day, the two things that you see are kids looking cool with guns and then the other thought is ‘well everybody’s got a gun maybe I should have one in case someone doesn’t like me,’” he said. “Kids are seeing that all day long: shootouts and guns, shootouts and guns.”

What used to be a fistfight can now more easily turn deadly when someone brandishes a gun.

For instance, 13-year-old Juano E. Peyton shot and killed Jaykwon Sharp, 14, in May 2019 while the two were fighting over a cellphone near Shady Lane Elementary School’s playground on the East Side. A 14-year-old was also wounded in the shooting. Peyton is to remain in juvenile jail until he’s at least 20½ years old.

‘Do you want to live?’

Dominic Jones, who works with juveniles as part of the Strive Towards Empowerment and Potential (STEP) program at the Columbus Urban League, said one of the first things he asks teens is “Do you want to live?”

"Some like (say), ‘Eh, I don't know.’ And for me that's always a question that we really tap into because at that point those kids aren't feeling like they have purpose. They aren't feeling empowered. They aren't feeling any sense of belonging,” Jones said during an October forum on gun violence and teens, hosted by The Columbus Dispatch in partnership with other organizations.

A lack of belonging can result in teens getting involved in gun use and gang violence, Jones said, just to feel included or cool.

Youths living in marginalized communities, with less of their basic needs like food and shelter addressed, are more likely to be at risk for being involved in violence, Twymon said.

Under Fire: 50 guns confiscated, 10 people shot, more than 100 gunshots detected all in 80 hours in Columbus

Add that to the fact that their brains are still developing, and it can lead to bad decisions, she said.

Children with mental illness aren't often involved in crime, though Twymon said that can be a factor in some cases.

Part of the reason for that is because youths often don’t have good access to mental health services, Twymon said, as there is a shortage of providers.

In Ohio, there are 331 adolescent psychiatrists and more than 2.6 million children, according to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. In Franklin County, there are 46 psychiatrists and 301,000 children or adolescents.

In schools, it is recommended that there should be one school counselor for every 250 students, but national statistics from the American School Counselor Association show the average is closer to 408 students per counselor.

"There are not enough therapists to meet the need,” Twymon said.

Remembering Layton Ridgedell

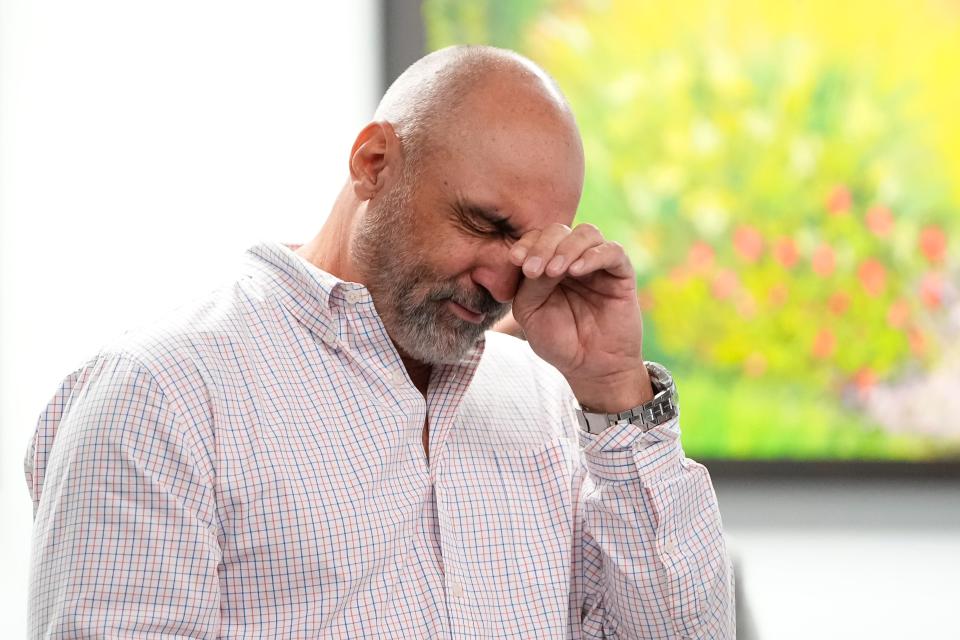

Before Layton Ridgedell was killed, he would go into his mom’s bedroom and talk to her about people he knew dying in shootings on the streets of Franklin County.

“He would say how scary it was, how he just couldn’t understand how kids are killing other kids,” said Shawna Bobst, Layton’s mom.

Bobst fought back tears as she shared this at an Oct. 10 Franklin County Juvenile Court hearing in Terrell’s case.

“I don't want (Layton) to just be a number. I don't want his whole life to be minimized to that alone,” she said.

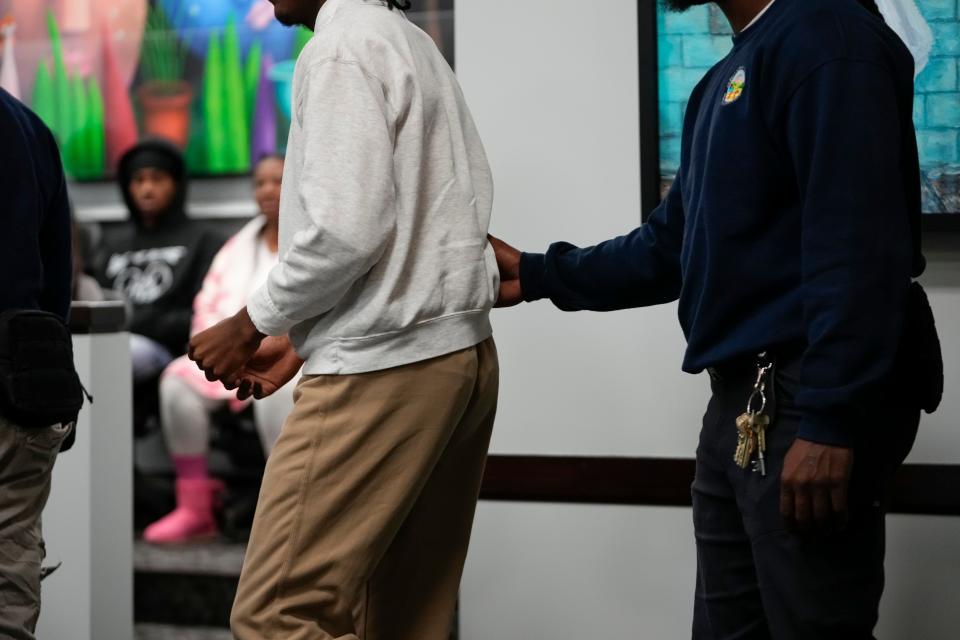

At the hearing, Juvenile Judge George Leach heard arguments on whether Terrell should be bound over to adult court or if he is capable of being rehabilitated in the juvenile justice system.

More on Layton's story: Two teenagers arrested in connection with double homicide in June on city's Northeast Side

Terrell, now 16, sat at a table across the courtroom, next to his attorney and parents. More of their family, including Terrell’s infant son, sat behind them.

Assistant Franklin County Prosecutor Chris Clark spent an hour presenting the texts Terrell, Makhy and Baron sent each other.

In the messages, they made jokes. They texted about hitting up different friends for a few dollars for gas money to get them to the deal.

They talked about wearing ski masks, but Makhy could not find his, so they all agreed that since they were doing this in the dark, they wouldn’t need them.

Terrell’s attorney, Kevin W. Zamora, said the boys were only talking hypothetically, using exaggerated banter.

Much of the plan they discussed matches the evidence though, according to prosecutors.

Layton and his friend — whom The Dispatch is not naming as he is not charged with a crime — got into the younger boys’ car and the trio told Layton’s friend to take out his gun’s clip, Clark said. He did so and police found the clip in the car later, Clark said, but he still had one bullet in the chamber.

When Makhy threatened Layton’s friend with a gun, the friend jumped out of the car to flee and shot Makhy in the head, according to Clark.

Layton was left behind with the two younger teens, prosecutors said.

Layton got out of the car but was shot six times, including in the head and back, by bullets from two different guns.

Clark called it an “execution.”

Leach will decide on Dec. 7 whether Terrell should be tried in adult court. The judge will also hold a hearing that day on arguments about whether Baron should be tried as an adult.

'The kids hunt deer, not each other'

Layton spent half his life in Beaver, a small village in Pike County, before Bobst moved the family to Columbus. She said moving was the worst decision of her life.

“People don’t do this in Beaver,” Bobst said. “The kids hunt deer, not each other.”

Bobst and three of her four surviving children live on Columbus’ Northeast Side near New Albany, a short walk away from the park in their neighborhood where Layton was killed. If they drive into the neighborhood one certain way, they drive right past the spot where Layton died on Caledonia Drive.

Bobst thinks about moving, but she’s torn. Because if she moves, she’ll have to leave behind Layton’s room, which she has mostly preserved. A half-eaten bag of Flaming Hot Cheetos is still on the nightstand.

Most nights, Bobst comes into Layton’s room and holds a maroon hoodie of his to her face, savoring his scent.

Layton was generous and funny, Bobst said. Of her four sons, Layton was the one who spent the most time with their little sister, Adalyn Harrington, now 12. He would brush her hair, tuck her in, play with Barbie dolls and take her trick-or-treating, Bobst said. Adalyn doesn’t really understand what happened to Layton, Bobst said, and she cried so much she could not attend the funeral.

'Everybody in this whole situation is hurting'

Clark said in court that unlike most defendants in juvenile court, Terrell has two involved parents who set rules and consequences.

Dionna Hicks told The Dispatch that before her son’s arrest on murder charges, Terrell was just a “normal kid” who played football, ran track and hung out with friends.

Terrell got in trouble with the law once before when he was arrested for carrying a gun and stealing a car in February 2021. After he pleaded guilty, he was sentenced to the juvenile equivalent of probation, which he completed. Hicks declined to comment on that case.

Hicks said Columbus kids are getting sucked into violence when they have too much idle, unsupervised time on their hands.

“And I think a lot of these kids are traumatized from what they're seeing out here just on a daily basis,” she said. “There is too much information being fed to these children that they don't have no business being involved with. They have to grow up too soon.”

Hicks maintains her son did not shoot Layton.

“My son is innocent. He was in the wrong place at the wrong time,” Hicks said.

Hicks said she is praying for Terrell to come home, and for everybody involved.

“Everybody in this whole situation is hurting. The city is hurting. Everybody's hurting,” she said.

That includes Terrell, who saw his best friend, Makhy, die in front of him and tried to rush him to the hospital, Hicks said.

In a letter Terrell wrote to Judge Leach, he said, “I’ve made plenty mistakes (sic) and at times surrounded myself with the wrong crowd, but I’m striving to do better.”

“I have the upmost (sic) respect for both families and hope and pray they don’t see me as a bad person and can cope with their losses as best as possible because I know how it feels to deal with death and it is honestly very, very difficult,” he said.

'We can stop this'

Court is the end of the road for youths like Terrell, so efforts to prevent crime before they enter the justice system are important, said Lead Franklin County Juvenile Judge Lasheyl N. Stroud in a prepared statement to The Dispatch.

"To truly address juvenile involvement in violent incidents, it will take action from all of us — including parents, families, law enforcement, schools, faith-based community and community partners," the statement reads.

Stroud and the other Franklin County juvenile judges declined to be interviewed for this article via a spokesperson, but are committed to working with the community, according to the statement.

Community speaks about teens and guns: Parents urged to 'do the work,' show love during Dispatch discussion on teen violence

One way the court has done so in the past is through programs like STEP, which offers youth involved in, or almost involved in, the juvenile justice system mentorship, leadership lessons, new ways to see things and more, said Candice Greenwade, associate vice president of social mobility at the Columbus Urban League.

The program helped to change Josh Martin's life. Before Martin, now 18, met Jones and STEP co-leader Ralph Carter a few years ago, he had given up.

The then 16-year-old got caught at school with a gun and went through the juvenile justice system. He was placed on an ankle monitor and stopped going to school.

"I felt like I was trapped," he said.

It wasn't until his mom heard of the STEP program from a friend and he and his sister started going that he began to see beyond his East Columbus neighborhood.

Mentors like Jones and Carter show what is possible for kids who may feel hopeless and who have turned to violence or self-harm, Greenwade said.

“Sometimes you don’t think you can do it unless you see it,” Greenwade said.

Jones worked on Martin's behalf with a judge to help him get off the ankle monitor after more than a year, Martin said. He hasn't gotten into any trouble since, and he graduated high school, is searching for a job and working to get his commercial driver's license.

The Buckeye Ranch — a private nonprofit group that offers mental, behavioral and emotional health services for children and families in central and southwest Ohio — also offers multiple programs that work with teens and their families, including two for youth involved in the justice system, Twymon said. More than 150 youth have taken part in those court-connected programs in the past year, said Twymon.

Experts are pinning their hopes on community programs like STEP and those at the Buckeye Ranch — as well as wider collaboration among those involved in young people's lives — to help reduce juvenile crime.

The STEP program worked for Martin, who thought there was nothing available to him other than the guns and violence he saw on the streets of his neighborhood but who now sees beyond those boundaries.

"I got to do a lot of stuff that I ain't never get to do before, like going to Washington, D.C.," said Martin, who now lives further East. "It helped me get out of the area."

He met the mayor, forged a closer relationship with his sister, learned communication skills, teamwork and learned how to socialize with his peers without the help of his cellphone.

"I never thought I'd talk to the mayor," Martin said. "That made me feel good. I got opportunity."

Seeing Jones and Carter and their lives also helped, he said, as they are family men. Carter also helped Martin make money over the summer through odd jobs.

But it will take more than programs like these to stem the problem of youth gun violence, experts say. It's also important to limit youth access to guns, through such efforts as better safe gun storage and more stringent laws on gun purchase and ownership.

Glock switches on Columbus streets: Here's how the tiny devices pose an outsized threat

There are already gun buyback programs, city offices handing out gun locks and anti-violence campaigns in Franklin County.

“We can stop this epidemic,” Sokol said. “We have a lot of the tools and strategies we need to end this.”

Martin's advice to younger kids: "it's not worth it."

"Sometimes some people do get out of hand over something that don't even matter," he said referring to "beefs" and other perceived slights that can so quickly escalate to gun violence.

But Martin said he's learned through STEP and the mentors he's made along the way, that we all need to focus more on things that make a real difference in life like family.

"That's what matters the most," he said.

dking@dispatch.com

@DanaeKing

jlaird@dispatch.com

@LairdWrites

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Surge in teen gun crimes, including murder, worries Columbus community