As shortages continue to strain nation's workforce, New England police struggle to hire

Police departments throughout New England report they’re still struggling to attract and retain officers amid a labor shortage also squeezing countless other professions and trades.

Law enforcement officials in all corners of the region, from the small towns to the big cities, have sounded the alarm on their hiring struggles for years as their number of applicants have dropped and retirements increased. Those calls have continued as the COVID-19 pandemic and national pleas for police reform — strengthened by the May 2020 murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis — have exerted additional pressure on the profession.

“The common comment around the table when chiefs get together is that the hiring pool is a puddle,” Salisbury, Massachusetts, Police Chief Thomas Fowler recently said in an interview with a USA TODAY Network newspaper. Fowler is a vice president of the Massachusetts Chiefs of Police Association.

That sentiment is backed up by a survey from the National Police Foundation that found 86% of the nation’s law enforcement agencies reported experiencing a staffing shortage in 2020.

Federal labor data does indicate law enforcement employment dipped in the past year, but not as much as the losses seen in other professions.

The overall U.S. economy lost 6% of its workers last year, with restaurants, schools and health care facilities among the hardest hit, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Comparatively, law enforcement decreased by less than 1%.

The law enforcement losses also come after a decade of steady expansion and that police departments have rarely been at full staffing levels, a recent news report produced by TIME and The Marshall Project noted.

Police officials are worried fewer officers could make communities less safe, and that addressing staffing shortages isn’t a quick fix because of the amount of time needed to train new officers.

The Burlington, Vermont, Police Department, according to Acting Chief Jon Murad, stopped conducting proactive patrols of Burlington’s downtown after city officials voted in 2020 to reallocate some of the department’s budget toward non-police responses to social problems, an approach some call "defunding" the police.

The city has since added police positions after a year in which Burlington — despite police data showing there was no overall spike in violent crime — hired a private security company and the Burlington Business Association launched an on-call program to provide “safety escorts” to people in downtown.

Advocates, meanwhile, argue the size of a department doesn’t automatically correlate with increased safety. They’ve also argued that years of racially charged high-profile cases prior to Floyd should prompt regions to rethink how they approach public safety.

“When we've got folks that we entrust with that much power, we have to have robust oversight over those folks,” Raul Fernandez, vice chair of the Brookline, Massachusetts, Select Board and the leader of the town’s Task Force to Reimagine Policing, recently told a USA TODAY Network newspaper. “We have to continuously ask questions about whether or not the amount of power we've given them, and the scope and scale of their duties is appropriate for today's circumstances.”

Police Reform: Maine keeps ruling police shootings as justified. Experts point to one needed reform.

Factors driving the law enforcement shortages

Police officials and non-police experts point to various issues contributing to New England’s overall labor shortage, not just the struggles to hire law enforcement officers.

Those factors include the increasing cost of living, the region’s affordable housing crisis, increased desire for better working conditions, a large portion of the working class reaching retirement age, and a shrinking middle class.

The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified those challenges, according to labor officials.

“The pandemic has created additional barriers preventing some from connecting to the labor force in the same capacity that they were before the pandemic,” Jessica Picard, communications manager for the Maine Department of Labor, told a USA TODAY Network newspaper this summer.

First responders, according to police officials, fire officials and racial justice advocates, also contend with the fact that their pay is below other industries that have fewer personal safety risks and better work-life balances.

“Let's face it, police work is a mentally, physically demanding job,” Yarmouth, Massachusetts, Police Lt. Cal Bogden recently told a USA TODAY Network newspaper.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data shows officers in Connecticut earned a higher mean wage — between $75,330 and $107,440 — than their counterparts in the other New England states. Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island officers earned a mean wage between $60,690 and $75,280, while officers in Maine and Vermont earned a mean wage between $50,960 and $60,290, according to the data.

Police officials believe the national dialogue around racial injustice and the defund the police movement are hurting staffing. Leo Rose, a Truro, Massachusetts police officer and union representative, told a USA TODAY Network newspaper this summer, “Nobody wants to be a cop anymore, just with the climate and everything that’s going on.”

Advocates have pushed back on those claims, while other police officials in the region have said the profession should change in response to the national dialogue.

“I think there has to be a concerted effort out there for law enforcement to reimagine and really market the police department in a different way,” Natick Police Chief James Hicks recently told a USA TODAY Network newspaper. “The departments have to go out there and show their potential officers that they’re a forward-thinking and progressive department.”

Police unions across the country have warned of mass resignations and shortages due to COVID vaccine mandates, but recent reports from national media outlets like Forbes indicate those mass resignations haven’t happened.

How staffing struggles are impacting New England police departments

In New England, law enforcement hiring struggles have manifested in various ways.

Brookline, Massachusetts, found this year through a survey of more than 100 police employees that 86% called morale poor. A majority said they had considered leaving. Officers voiced concerns both within the department and greater community. Pay was among their primary complaints.

Departments throughout New England have said they’ve had to spend more time recruiting officers because the number of people applying has dropped. The pool is further reduced through applicant screening, department officials have said.

New Hampshire is experiencing this despite the fact that the state’s full- and part-time police academies continue to graduate full classes, John Scippa, director of the State Police Academy, said in March. Police officials say this indicates departments are cannibalizing each other as they compete in the shallow applicant pool.

Overtime and officer fatigue have gone up in many areas struggling to fill positions, according to police and city leaders in Connecticut and elsewhere in the region.

How departments are responding to their staffing struggles

Departments throughout New England have implemented new recruitment strategies and incentive programs to grow their ranks.

Gardiner, Maine, is among many departments across the country offering hiring bonuses to attract officers. Eligible new officers will be paid a $15,000 bonus over three years, the Kennebec Journal and Morning Sentinel have reported.

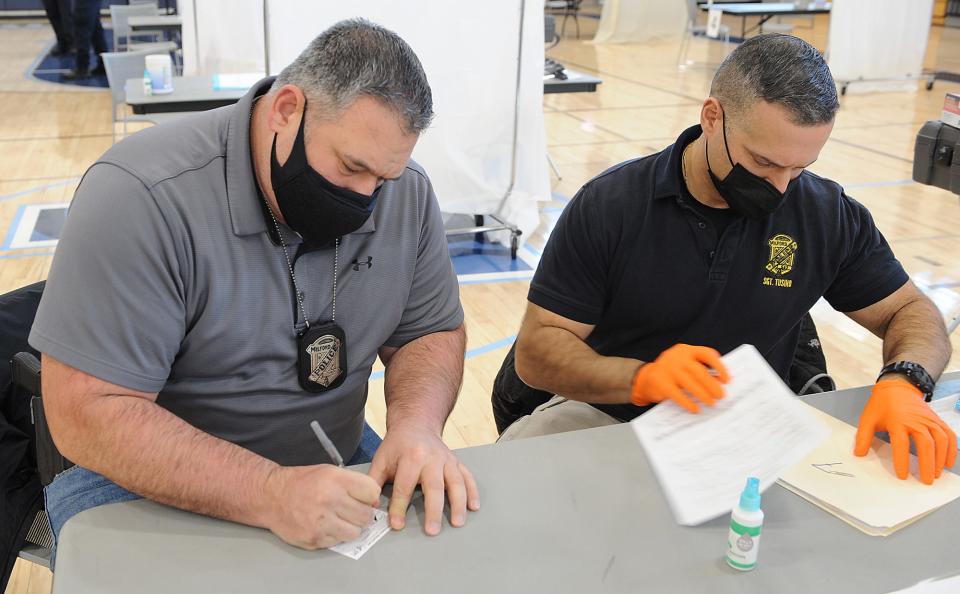

Massachusetts used to offer bonuses to officers attaining associate, bachelor's or master’s degrees, but did away with it years ago. The Milford Police Department uses its own town funds to offer a similar educational incentive.

Burlington, Vermont, city councilors unanimously approved in September a plan to use more than $850,000 in COVID-19 relief money toward attracting and retaining city police officers.

Some departments have begun discussing ways to recruit more women because national statistics have shown women only account for about 1 out of every 8 police officers — less than 13%.

Those efforts coincide with recruitment initiatives designed to find diverse candidates and foster connections with local youth. Brockton, Massachusetts, launched a new cadet program and the junior cadet program this year in such an attempt.

More and more police Massachusetts departments have stopped using the civil service system to hire and promote officers. They argue the method limits candidates available to a department to two or three candidates instead of a wide pool.

What is civil service: Aimed at preventing nepotism and discrimination, an 1880s program is smothering today's police

“Civil Service was enacted over 100 years ago to make public employment hiring and promotion processes uniform and fair,” Det. Lt. Eric McAvene of the Gardner Police Department, a union official, wrote in a letter ahead of Gardner’s decision this summer to stop using the civil service system. “Unfortunately, the process has become antiquated and extremely cumbersome for today’s needs. A more up-to-date and thorough evaluation, designed with specific community needs in mind, should be implemented… The city should have the latitude to develop its own, legally vetted, hiring and promotional processes to address the unique needs of our community.”

USA TODAY Network reporters Michaela Chesin, Angeljean Chiaramida, Denise Coffey, Kathi Scrizzi Driscoll, Jeannette Hinkle, Cynthia McCormick, Norman Miller, Elizabeth Murray, Shawn P. Sullivan, Beth Treffeisen and Bronwen Walsh contributed to this story.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY NETWORK: Hiring police officers is a strain for New England police departments