Who killed heir to Reynolds tobacco fortune? Museum exhibit explores NC unsolved mystery

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Forty thousand guests each year tour the 1917 Reynolda House to learn about its original Arts and Crafts furnishings, its vast collection of American art and the indoor bowling alley and squash courts that helped make the 64-room “bungalow” the Biltmore of the Piedmont.

What docents never wanted to talk about was the subject that loomed the largest in the rambling country home built for the family of the founder of R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company:

Who shot Z. Smith Reynolds?

After changing the subject for 91 years, the estate finally tells what it knows about the mysterious shooting of R.J. Reynolds’ youngest son in an upstairs room of the house in 1932, through an exhibit that runs until Dec. 31. It’s called “Smith & Libby: Two Rings, Seven Months, One Bullet.”

The exhibit includes information taken from newspapers and the estate’s archives along with artifacts and memorabilia pulled from Reynolda’s holdings or borrowed from collectors who have been fascinated by the case and its characters for decades. The exhibit is the result of exhaustive research by Phil Archer, deputy director of the museum, who tried — as investigators, a grand jury, Reynolds family members, news reporters and the public did nearly a century ago — to determine whether Reynolds’ death was a suicide, an accident or a murder.

Who were the Reynoldses?

Richard Joshua Reynolds, born in 1850 on a tobacco plantation in Patrick County, Va., moved to the crossroads community of Winston in 1874 to start his own tobacco manufacturing company. He introduced Prince Albert Pipe Tobacco in 1907 and Camel cigarettes in 1913. They became two of the most popular tobacco products in the U.S. and Reynolds, better known as R.J. Reynolds, became the wealthiest man in North Carolina.

At the age of 54, Reynolds married Katharine Smith, his first cousin once removed, and together the couple bought an expanse of land two miles outside of town for the construction of a country house and working farm where Katharine wanted to test new farming methods and notions of healthy living.

It took three years and $200,000 (the 2023 equivalent of more than $4.8 million) to build the home.

The couple and their children — two daughters and two sons — moved into the house in December 1917, with R.J. Reynolds already ailing from what is now believed to have been pancreatic cancer. He died the next year.

Growing up at Reynolda

Katharine stayed at Reynolda after her husband’s death, overseeing the family, the farm, the gardens and the adjacent village of 100 laborers required to keep it all running.

In 1921, she married Edward Johnston, the superintendent of her Reynolda School, and moved with him into a cottage on the property, leaving the Reynolds children in the main house largely under the care of a governess. Despite serious heart problems that made pregnancy dangerous for her, she was determined to have a child with Johnston, some 13 years her junior.

The couple’s firstborn, a daughter, died shortly after birth. A second child, a son, survived but the birth caused Katharine to suffer an embolism that took her life a few days later in May 1924.

After her death, Johnston took the baby to Baltimore and the orphaned Reynolds children went to live with an uncle. Zachary Smith Reynolds, who went by Smith, was 12 years old.

The estate was placed into a trust awaiting the children’s coming of age.

Z. Smith Reynolds on his own

Like his older brother, Dick, Smith Reynolds became fascinated with airplanes, which Archer attributes in part to their mother’s having invited barnstormers to land on Reynolda’s front lawn after the end of World War I and to Charles Lindbergh’s successful 1927 trans-Atlantic flight.

After Dick Reynolds dropped out of N.C. State and started Reynolds Aviation, Smith left high school and went to work for the company. At 16, Smith was the nation’s youngest licensed pilot, his certificate bearing the signature of Orville Wright.

The brothers are said to have used the lawn at Reynolda as an airfield and performed stunts to scare their sisters.

In November 1929, days after he turned 18, Smith Reynolds married Anne Ludlow Cannon of the Cannon Mills textile family. The girl’s father was reported to have insisted on the wedding and gone with the young couple to South Carolina to ensure it happened.

Biographers have said it was a rocky union and the pair fought in front of friends and family. Though Anne was pregnant, she and the young Reynolds separated in early 1930. Their daughter was born that August.

Libby: A star in his eye

In April of that year, Reynolds went to Baltimore to see his Broadway-producer friend Dwight Deere Wiman’s touring production of “The Little Show,” featuring college-educated actress and torch singer Libby Holman. It was her breakthrough role, in which she performed her signature song, “Moanin’ Low,” borrowing stylistically from African American female singers.

Reynolds was smitten and began pursuing the free-spirited Holman with the same determination he had applied to flight lessons. He would fly to cities where she was performing and arrive at the theater in his aviator gear. When “The Little Show” went to Broadway, he watched nearly every performance from the front row.

Holman told friends that her suitor had asked her to marry him not long after meeting her, and asked her repeatedly over the next year and a half, suggesting he might kill himself if she didn’t.

Reynolds arranged for a divorce from Anne Cannon in Reno, Nev., in November 1931 and, through they argued frequently too, he persuaded Holman to marry him before a justice of the peace in a town in Michigan six days later.

From there, Holman went back on tour and Reynolds took off on what was supposed to be a record-breaking 17,000-mile trip from London to Hong Kong in a biplane. When the plane broke down, he had to make the last leg of the trip on an oil freighter but rendezvoused in Hong Kong to begin a honeymoon with his new wife.

When they returned to the U.S., the couple moved into Reynolda House to spend the summer of 1932.

The fateful night

On July 5, Reynolds and Holman hosted a small birthday party for a friend at the estate. In accounts of the event later, those present said much of the evening was spent at or around the boathouse on 16-acre Lake Katharine, an impoundment the Reynolds family had built on Silas Creek behind the house.

It was a party; there was plenty of moonshine, guests said later, despite the rules of Prohibition. Some said Holman had engaged in a drinking contest with another guest.

After the party broke up, the only ones left in the house were Reynolds, Holman, Reynolds’ longtime friend and newly hired assistant Albert “Ab” Walker, and Blanche Yurka, a theater friend of Libby’s.

Sometime after midnight, Reynolds and Holman went upstairs to the bedroom on the east end of the house, one of several rooms with sleeping porches attached.

Holman would later say her only memory of the day was waking up on the bed on the porch when Reynolds called her name, and seeing a flash before he fell onto her.

Diverging stories

Yurka, who was in a bedroom near the other end of the house, later told investigators she heard what sounded like a hysterical voice around 1 a.m., and ran toward the balcony overlooking the first-floor reception area. She saw Walker below, called to him, and said he ran up the stairs toward Reynolds’ and Holman’s room.

Yurka said Walker and Holman came out of the room carrying Reynolds, and she went to help, all three of them bringing him downstairs.

Records show Walker called an ambulance at some point, but deciding they couldn’t wait for help to arrive, Walker, Yurka and Holman carried Reynolds out of the house and put him in a car. Walker drove to the hospital with Yurka in the backseat holding Reynolds’ head and Holman in the front passenger seat.

Reynolds was still alive when they reached Baptist Hospital but died four hours later.

He was 20 years old.

It was suicide. No, it was murder. Maybe.

The death originally was ruled a suicide, based on Holman’s account. But the more questions investigators tried to ask, the less consistent the answers became.

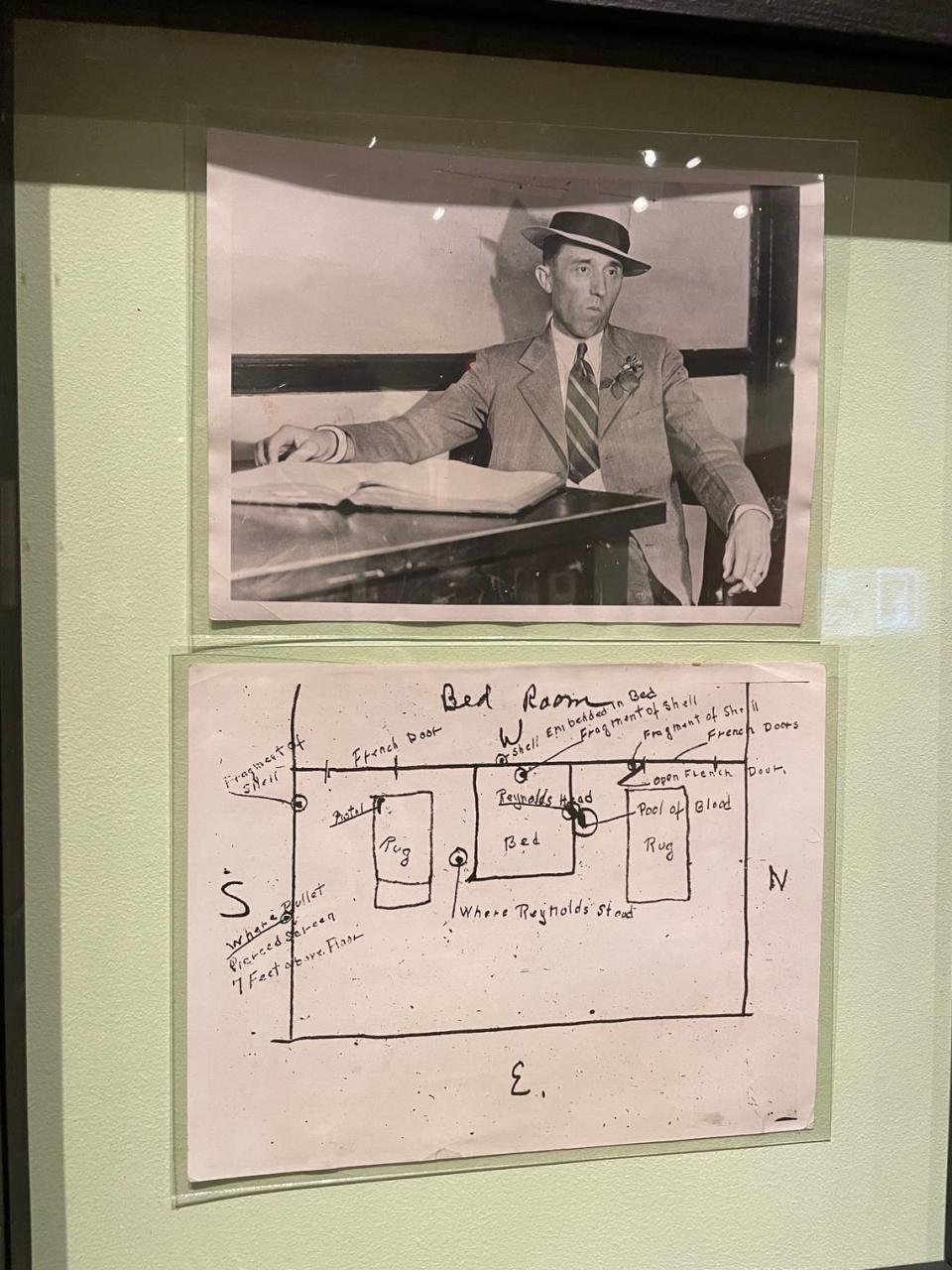

A coroner’s inquiry, held in the very house where the shooting occurred, led investigators to convene a grand jury and bring first-degree murder charges against Holman, who was accused of pulling the trigger, and Walker, who was charged as an accomplice.

News media had descended on Reynolda, sending dispatches back to New York and elsewhere. Unable to get information from law enforcement, they leaned heavily on speculation, including about whether Holman and Walker had had an affair and whether the baby she was now known to be carrying might have been his and not Reynolds’.

It turned out Reynolds had suggested many times to different people, beginning in high school and at least once the night of the party, that he might kill himself. But the trajectory of the bullet that entered his right temple and exited out the porch screen couldn’t have been fired by someone standing up as Holman said he had been.

For every bit of evidence or testimony that supported a suicide, it seemed there was another piece that suggested murder.

The family, Archer said, with its distaste for scandal, couldn’t bear the possibility that a Reynolds baby might be born in prison. So when police struggled to find enough evidence to ensure convictions, the family asked that the charges — and as far as they were concerned, the whole subject — be dropped.

They were.

Lifting the taboo

Though the mystery sparked the production of three different movies and a library shelf worth of biographies and books, it wasn’t discussed at Reynolda, which is now owned by Wake Forest University, or among the board of the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, the philanthropy launched with the inheritance that the youngest Reynolds didn’t live long enough to collect.

But then, Archer said, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a local television station approached the museum about doing a story on an anniversary of the case, and for the first time ever, Reynolds family members and other descendants of those involved in the 1930s were willing to let Reynolda speak about what had happened in the house.

Response was so positive that Archer decided to put together the “Smith & Libby” exhibit, using the estate’s remarkable collection and the calm perspective that comes with the passage of time.

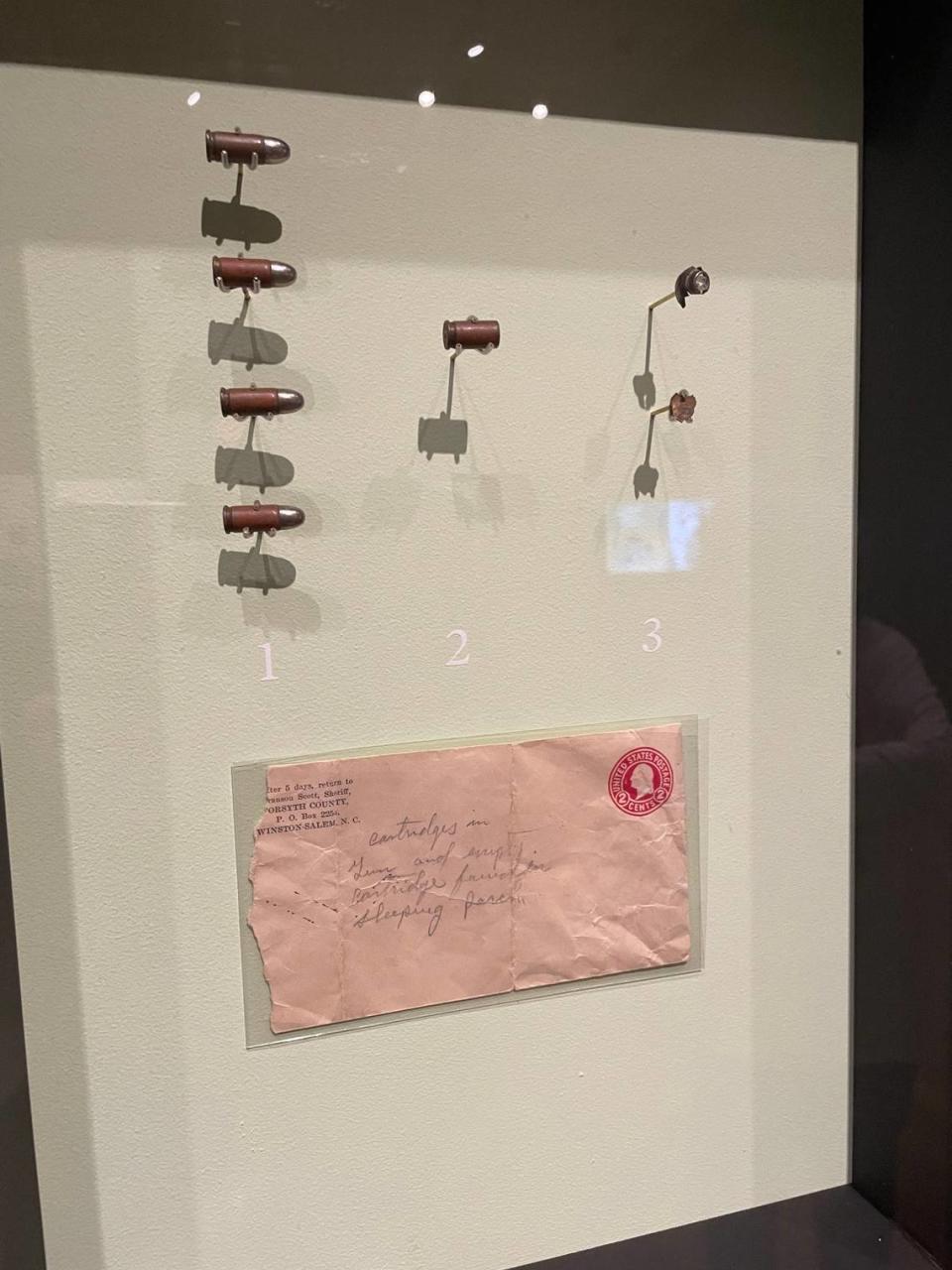

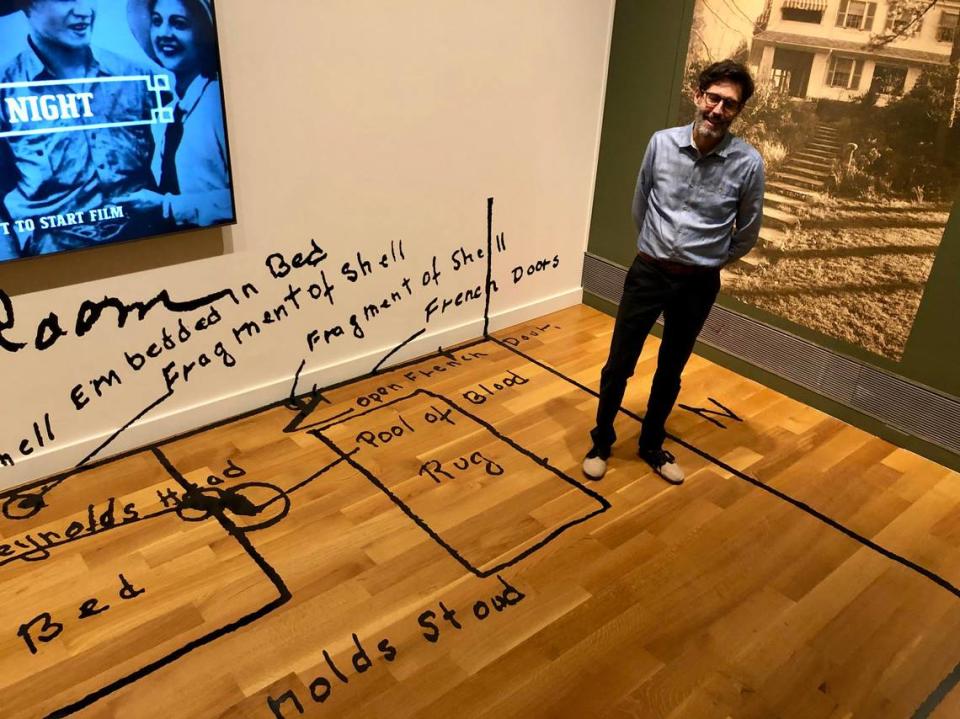

The display, in the main exhibit hall at the museum, begins with a vintage newsreel that played before the start of movies as the case was playing out. It describes Reynolds’ near-obsession with Holman and lays out the events that culminated with that single gunshot, letting visitors stand in a life-sized enlargement of the sheriff’s sketch of the shooting scene. It includes fragments from the bullet casing that were handed over along with the rest of the evidence gathered in the investigation.

For the first time since the house opened as a museum in the 1960s, the porch where Reynolds was shot and the bedroom it is attached to are included in the house tour.

Even with the perspective of 90 years and all the resources Archer was able to gather, the exhibit doesn’t definitively solve the case. But Archer, who has worked at the museum since 1997, says that’s not really what he set out to do.

“The first thing was, I didn’t want to get any of the story wrong,” he said, “because for all their flaws, I have a lot of affection and respect for all the people involved.

“But in the end, it was just refreshing to tell the story ourselves and to show that we didn’t need to be so fearful about the truth.”

Visit Reynolda and see the ‘Smith & Libby’ exhibit

▪ “Smith & Libby: Two Rings, Seven Months, One Bullet,” runs through Dec. 31 at Reynolda House Museum of American Art, 2250 Reynolda Road, Winston-Salem.

▪ Hours: The museum is open Tuesdays through Saturdays 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., and Sundays 1:30 p.m. to 4:30 p.m.

▪ Cost: Tickets are $18 and can be purchased online at reynolda.org.

The garden and grounds are open during daylight hours year-round, at no charge.