Shot in her face at age 6, Kansas City survivor knows: ‘I gotta be here for a reason’

Hers was one among 50 emails, but the only one that shocked.

The sender: Tashay Campbell.

“Hello u might not remember me u did my story and the Kansas City star 30 years ago how u doing ? And thank you so much.”

Remember?

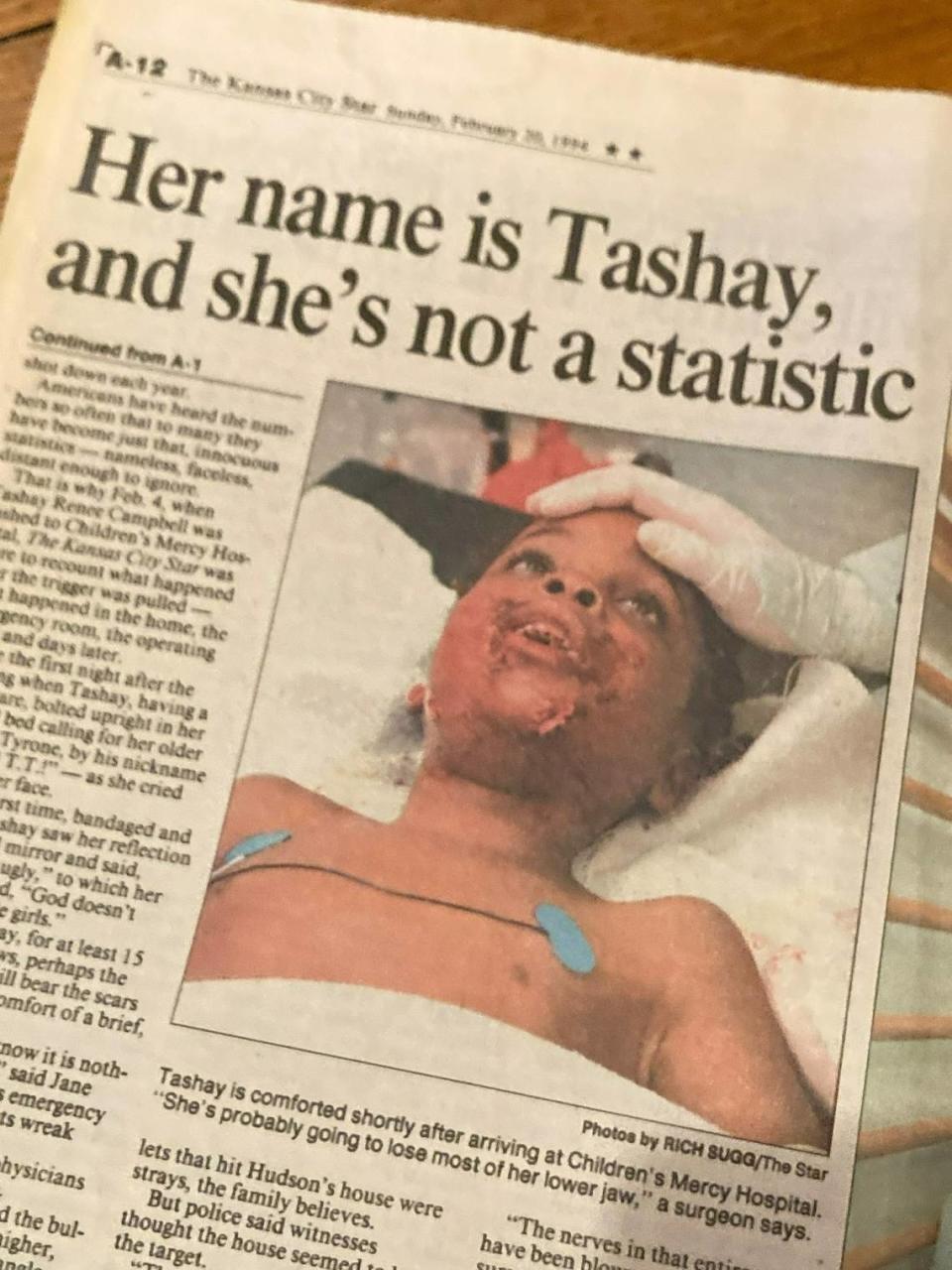

All these years later, the image of 6-year-old Tashay on the night of Feb. 4, 1994, remained unforgettable: the bottom of her face caked in blood, her jawbone and teeth pulverized.

“Duck!” her grandmother Diane Hudson had yelled. It was just before the second of two stray bullets, shot by gunmen in cars, pierced her home at 50th Street and The Paseo, blasting holes through the skin and muscle of Tashay’s cheeks while she played with her cousins and sister on the mattress of a fold-out couch. Tashay’s flesh hung in tatters.

At Children’s Mercy Hospital’s emergency room, she was the girl who never cried. She was the quiet child who, even a year later, didn’t want to speak, at least not to strangers. Now, with the 30th anniversary ahead, she was reaching out to talk.

“Oh my god, Tashay Campbell!” I emailed back. ”Are you kidding me? I never have forgotten you.”

Last week, she arrived early for lunch at a Crossroads restaurant a 36-year-old woman — 4-foot-9, decked out in the Nike gear she loves: pink knit hat, pink shirt, white sneakers. Her facial scars are hard to see unless she tilts her head and points them out. A dimple beneath her chin — it remains numb since the shooting. A faded scar creates a pink crescent along her right jawline.

When Tashay laughs, it’s light, a chortle, mouth closed. When she smiles, it’s close-lipped, a habit from years of self-consciously hiding her teeth. Her initial presence seems demure, but that is not entirely right.

“I’m really strong. I’ve been through a lot,” Tashay said, although even now, 30 years on, she wonders what it was all about.

“I think that all the time: Why did it have to be me? Why did that bullet have to come through my face because somebody else was angry outside? I hate that I had to go through that at a young age.”

In 1994, The Star set out to write about children and gun violence in an intimate way.

Children’s Mercy, even then, was treating ever more kids whose lives were ripped apart by bullets, not just at home, but also as collateral damage from drug wars and drive-by shootings. More than 5,800 young people in the United States, 16 children and teens a day, died by guns in 1994. Gun violence was a major public health issue then, as it still is.

In 2020 guns for the first time became the leading cause of death for children (4,368), outpacing deaths from motor vehicle crashes. That number rose in 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic only made matters worse, with kids at home and closer to guns.

No words. No tears.

At the restaurant, neither of us recognized the other, nor would we have. Those days, 30 years ago, were chaotic.

The Star’s account of Tashay’s trauma was graphic and some of it confused.

It described how the bullet exploded into Tashay’s right cheek (it actually entered her left and exited the right) shattering her jaw and her baby teeth. It pulverized some of the front permanent teeth that lay beneath. Her younger sister, Tashyra, and eight cousins who were at their grandmother’s home for a sleepover, screamed, “Nay Nay’s been shot! Nay Nay’s been shot!” using her nickname from Renee, her middle name.

It described the operating room — surgeons tweezing one rice-sized piece of bone after another from her jaw that, one doctor said, had been turned to “cornflakes.” Pieces plinked as they were dropped into a dish. Nerves in Tashay’s jaw had been “blown out,” the dental surgeon, Taylor Markle, said that night.

“She’s not going to be just fine,” he said. “No way. She could have pain the rest of her life. The best scenario is that she’ll be numb.”

Tashay doesn’t remember being struck.

“I couldn’t feel it,” she said.

Her mother, Chantell Mullins, who was 25 at that time, last week told of bursting into the house after the bullets flew. She and her sister-in-law had just pulled up to bring Gates Bar-B-Q to the kids. They took cover as gunshots rained from the two cars, heading east on 51st Street, two bullets crashing through a side window.

The women pushed through the front door.

“That’s when my mother says, ‘Your baby’s been shot!. … Yours, Chantell. And by the time she said that, she (Tashay) was walking toward me. It looked like someone had put a gun under her chin.”

Through it all, Tashay was silent. No words. No tears.

Just moments before paramedics arrived, the 6-year-old went to a bathroom, her mother said, stared in a mirror, and quietly began singing the song from her favorite television show, “Barney & Friends,” about a purple dinosaur.

“I love you, you love me …”

“That night was horrible,” Mullins said.

Tashay was whisked into the emergency room and on to a treatment bed. Bright lights lit her wounds.

“I just remember everybody coming in the hospital crying,” Tashay said. “And I’m just looking like, ‘Why?’”

The initial story was published on the front page, Sunday, Feb. 20. Television news crews descended three days later when Tashay was released from the hospital. Her father, Tyrone Campbell, carrying a bouquet of balloons, dressed as Barney the purple dinosaur. A white limousine spirited Tashay away. A year later, when The Star did a follow-up, Mullins insisted her daughter was doing fine.

“Except,” Mullins said then.

Except?

“Except she never talks about the shooting,” her mother said. “And she’s afraid to go out at night.”

Time moved on.

Over the interceding years, Tashay said, she doesn’t remember receiving a single minute of psychological counseling.

Although Missouri has a crime victims compensation fund, which would have helped with bills, she and her family received nothing because of what the family believes to be the assumption by police (suggested in every story) that the bullets may have been meant for Tashay’s dad, who had a criminal past.

That assertion never bore out.

“They did her wrong,” Hudson, her grandmother, said last week. “She was an innocent person.”

Police also never discovered who fired the bullet, but Tashay’s family said that the word on the street was the shooter eventually died by gunfire.

The sound frightens her still.

“I hate guns,” she said.

‘I’m still here’

Tashay is measured in assessing the years past.

“I’ve had a good life,” she said. “I’ve had some bad times. Overall, it’s good. … I’m still here.”

She does not take that lightly, knowing that had she crouched a couple inches lower, the bullet could have entered her brain. Rise up an inch higher, and it might have pierced the major vessels in her neck, killing her either way.

The hardest parts of her life are mostly in the past.

In school, classmates would mock her about her height. Others pointed out the scars on her face.

“Some days I would take my article,” Tashay said. She got the newspaper laminated and has kept it since. She would bring it to school because the photos alone showed more than she could explain. “They would say, ‘Oh, you got shot.’”

Family brought other trials. Her mother was imprisoned from 1999 until 2006 for her role in the robbery of a Brinks truck, federal court records show. Her father, now living in Illinois, would also do a short period of time behind bars. Even more recently, in 2021, her older brother, T.T. Campbell, now 38 and living in the Kansas City area, said he finished seven years in prison on drug and other charges.

“Mom went away,” her brother recalled of Tashay’s childhood. “We split up, had to live with our grandma. They would keep crying every other week about my mom.” She had a hard time with other boys, he said, because of the scars on her face.

Tashay has no children, has not married and is unsure if she ever wants to. “Boys aren’t faithful,” she said, laughing. “Gotta find me a good man.”

A serious threat arose three years ago when high blood pressure led to a stroke, she said, that has affected her left eye.

But for all that, Tashay said, she feels generally content. Her younger sister, Tashyra, who is 34, is her best friend.

“We’re real tight. We’re real close,” Tashay said.

They’re rarely apart. Tashay is a massive Chiefs fan, enjoys playing the slots at the casinos, has a day care job she likes and, at church, “I love to see my grandma get the Holy Ghost.”

From the time she was shot, one of her most lasting and unexpected relationships has been with Brett Ferguson, now the chair of oral surgery at University Health, formerly Truman Medical Center.

He has seen her through at least five significant surgeries, fortunate to be fewer than anyone expected. Tashay’s mother said that Ferguson has been like a surrogate father.

“It is one of those things,” Ferguson, 70, told The Star. “You always try to tell yourself that you don’t have a personal relationship with patients. But she was just somebody who struck me.”

After Tashay was injured, Ferguson delivered the family Christmas gifts. When Tashay’s mom went away to prison, Ferguson became a support. He has helped pay her rent and buy her groceries. To him, she is that child from 1994.

“She’s just a sweet little girl,” he said. “You know, you just feel so bad for a little 6-year-old. All she was doing was watching TV at Grandma’s house.

“Every time I go down Paseo, I think about Tashay. Every time.”

Tashay is still missing some of her permanent lower teeth. Moments still exist, she said, when she looks in the mirror and dislikes what she sees.

“Some days, when I think about it, I hate how my mouth looks,” she said.

But more recently she has also made a turn. What she once saw as a victim’s scars, she said, she sees more and more as the scars of a survivor.

Why she survived, why she has had to bear the wounds of that split second, is still something she’s not sure about.

“I wonder, like, I gotta be here for a reason,” she said.

Sometimes that reason is as visible as a scar. “I’m here to tell my story.”