Showdown vote coming for the Urban Development Boundary in South Miami-Dade County

The politics of development and the environment in Miami-Dade County could be reset Thursday as a new county commission decides whether to let developers build warehouses on 800 acres of farmland off the Florida Turnpike.

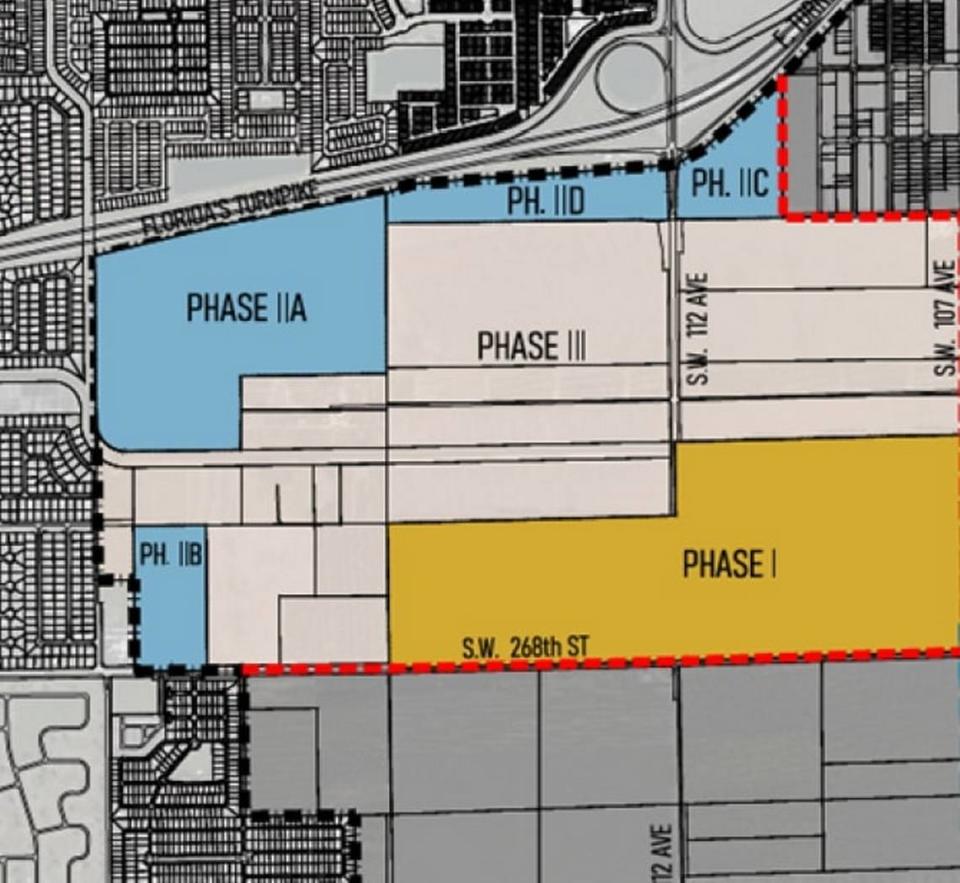

Developers pushing what would be one of the county’s largest industrial centers, with 9 million square feet of commercial space near Homestead, first need commissioners to expand Miami-Dade’s Urban Development Boundary to include the 800-acre site.

That’s usually an uphill task, and commissioners last altered the “UDB” in 2013, when it was expanded to include about 500 acres in the Doral area already encircled by development.

But this UDB vote is the first for a commission with six of its 13 seats filled by members who took office after the November elections. It’s also the first UDB fight for a new mayor, Daniella Levine Cava, a longtime environmental advocate whose administration opposes the project.

Thursday’s commission vote after a 9:30 a.m. public hearing in the Stephen P. Clark Center wouldn’t be the final decision on whether to expand the Urban Development Boundary. If enough commissioners vote yes, they would still have to take a final vote to move the line after a state review.

The Urban Development Boundary forms the outer edges of where companies can construct housing subdivisions, strip malls and warehouse centers, and creates a development buffer designed to protect the Everglades and Miami-Dade’s declining footprint of farmland.

Environmental groups and county planners oppose expanding the Urban Development Boundary for the project, saying warehouses can be built elsewhere, closer to existing facilities.

The project sits in an area that’s already designated for expansion of the Urban Development Boundary once the county determines there isn’t enough buildable land inside the UDB.

An Aug. 27 report by the county’s Regulatory and Economic Resources Department, however, said South Miami-Dade already has enough vacant industrial land to accommodate new projects through 2040. If the proposed South Dade Logistics and Technology District industrial park gets built, it would take more than 100 years for the market to absorb the new space, the report found.

“If approved as filed, the application would encourage the proliferation of urban sprawl,” the report said.

The developers requesting the UDB expansion are pitching it as a way to bring well-paying warehouse jobs to South Miami-Dade, an affordable place to live but where many residents are forced to commute north to the Doral and Miami areas for similar work.

An economist hired for the project forecasts nearly 12,000 jobs once the complex is fully constructed.

“Far from creating sprawl, this project can be part of the county’s effort to reverse sprawl,” Graham Penn, a lobbyist and land-use lawyer for the project, said at a Planning Advisory Board hearing on Aug. 23 before the panel endorsed the proposed UDB change. “South Dade is out of balance now. It’s been out of balance for decades.”

With the proposed industrial park, hotel and shopping center sitting in a coastal-flood area two miles west from Biscayne Bay, opponents say the project would create yet another development in a low-lying spot prone to catastrophic floods as sea levels rise and storms worsen from climate change.

They also argue losing the farmland will stymie efforts to protect nearby Biscayne Bay from pollution by eliminating the filtration benefits of undeveloped land.

“We cannot look at the bay as the coast,” said Paola Ferreira, executive director of the Tropical Audubon Society. “We have to look at it as a watershed. By placing 800 acres of industrial development near the bay, we are removing a watershed element — a place that is providing habitat and an ecosystem that helps support the health of the bay.”

One objection county planning staff had to the application: developers only control a portion of the 800 acres that would be brought into the Urban Development Boundary.

While the developers provided a detailed zoning application for the first two phases of the project, those only cover about half of the land. The remainder, more than 400 acres, is reserved for what’s billed as the third phase of the project, but involves land owned by others that aren’t part of the development team.

“There are significant planning concerns as it relates to infrastructure in the Phase III area, which is simply a large gap in the application,” the county report read.

About 155 acres of the farmland in the project’s third phase is owned by companies linked to retired banking magnate Leonard Abess.

A lawyer for his Archimedes holding companies, Michael Kreitzer, wrote the county’s planning staff on June 9 objecting to his client’s lands being subject to restrictions that would let the other farmland be developed in earlier phases.

He called the developers “land speculators” for owning so little of the site they want developed. He also warned of the “very real risk” that Miami-Dade would approve the UDB move without adequate details about development of the third phase of the project.

County records show the Abess companies have since applied for the kind of zoning changes that would allow for industrial projects if the UDB boundary is extended.

Developers Stephen Blumenthal, Jose Hevia and partners have assembled a sprawling team of leading lobbyists for the vote. That includes Hugo Arza, Jeff Bercow, Ron Book, Brian May, Juan Mayol and James McQueen, who was chief of staff to Commissioner Keon Hardemon when he was on the Miami City Commission.

The project sits in District 8, represented by the board’s newest member, Danielle Cohen Higgins. She’s the only commissioner not to have won a commission election, since she was appointed to the vacant seat in December after Levine Cava, the former District 8 commissioner, became mayor.

Cohen Higgins faces her first election in the 2022 August primary, and hasn’t announced her position on the UDB proposal. Should the project advance, South Miami-Dade should expect another UDB debate waiting in the wings.

The commissioner representing neighboring District 9, Kionne McGhee, has already announced his yes vote for the industrial park. He also wants to expand the UDB in his district to allow more development.

“There is a clear need for good paying, local jobs for South Dade’s underutilized workforce,” McGhee said in announcing his vote in favor of the District 8 project. “This is a historic opportunity to transform the local economy.”