Shrimpers and scientists collaborate to study parasite worsened by climate change

Georgia's shrimpers are already facing plenty of challenges like high gas prices, inflation and international competition. But climate change is exacerbating a new problem: black gill, a parasite that is decreasing shrimp populations and is worsening with rising ocean temperatures.

On Dec. 15, the University of Georgia's Skidaway Institute of Oceanography invited shrimpers, researchers and other local stakeholders aboard the R/V Savannah to collect samples in the Wassaw Sound and discuss the current research and on-the-water observations of black gill.

What is black gill?

Black gill is a parasite that lodges itself into shrimps' gills and feeds on that tissue. It's a ciliate — a single-celled organism. It gets its name from the shrimp's immune response to the invader, which turns the gills black as the shrimp's body tries to fight off the intruder.

Luckily, University of Georgia professor and researcher Marc Frischer said black gill does not harm people — it's totally edible, but the aesthetics could be a problem for shrimpers selling the product.

While it won't hurt humans who eat it, black gill does have the potential to kill shrimp. With the parasite lodged in its gills, a shrimp can't breathe as well, and it is more likely to become weaker and be more susceptible to being eaten by a predator. Many of the shrimp with black gill die, but a lucky few will molt their gills — something shrimp do every couple of weeks — and get a new lease on life without the parasite, unless it is re-infected.

More:Black gill parasite causes fall harvest declines in Georgia White Shrimp

Especially since black gill is usually easy to spot in a shrimp, shrimpers have known about the parasite for decades, with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources officially detecting it off the coast of Cumberland Island in 1996.

Since 2016, Frischer said the parasite has been more common and the span of the year it is most active has been growing. He said when his team collects samples they look at a variety of factors, like oxygen in the water or temperature, but none of them correlated to the prevalence of the parasite except for global climate indices. When there's a warmer winter, the following fall the black gill gets significantly worse: a correlation.

Shrimpers at the meeting nodded their heads: there used to be winters so cold water would freeze to the boats' decks, but they hadn't had one of those in a long time, shrimper Wynn Gale said.

Testing for black gill

Lab manager for Frischer's lab, Anita Minniefield, kept a steady balance aboard the R/V Savannah while delicately extracting gills from shrimp caught for surveying. She documents the sex and length of the shrimp, and notes if they have black gill and if so, how bad the condition is based on a color chart ranging from light to dark. She places the gills in ethanol to preserve them until they make it to the lab on land, where researchers run a PCR test to determine if the shrimp has black gill: like a COVID-19 test for the small crustaceans. But unlike a virus, Frischer said the black gill isn't evolving or changing at all.

Sampling and understanding the extent of the parasite is essential, Frischer said. It helps groups manage the fishery, but also be aware of how the fishery's health and populations might affect the shrimpers whose livelihoods depend on the resource.

More:Savannah scientists continue study of black gill in shrimp

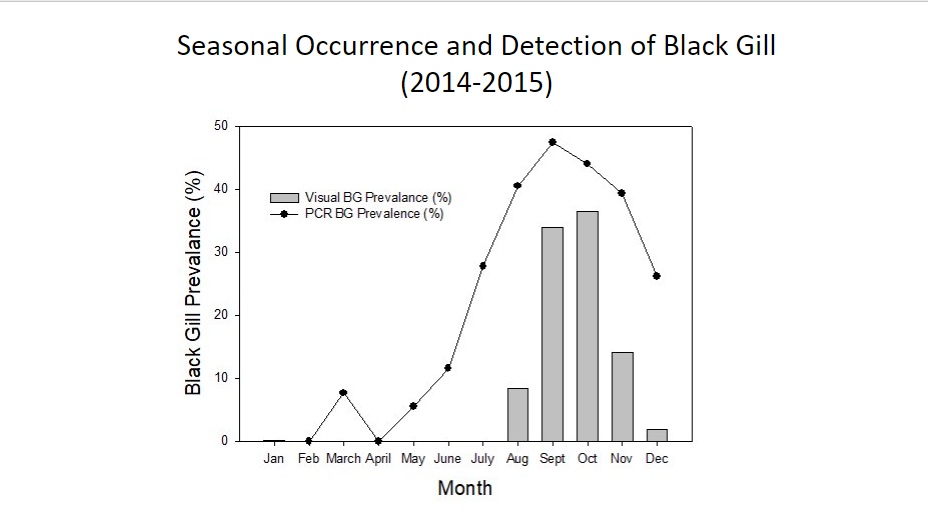

From 2014 to 2015, Frischer's team sampled off the coast of Georgia and found black gill in just under 50% of shrimp sampled at the parasite's height for the year in September. Sampling from 2016 to 2020 put that statistic closer to 80%. While the parasite was detected mostly in August through December in 2014, the 2016 to 2020 data saw a black gill season stretching from June to December.

Warm water temperatures rising

Wynn Gale, captain of the Big Cobb, is a shrimper through and through: it's his main source of income, and he's deeply involved in the local shrimping community down in Darien. In his own experience, he said he's recognized how the changing climate has manifested in the shrimp fishery in coastal Georgia.

"We don't have cold water crop like we used to have," he said. "Right around December, they would always pop out for about two weeks." He said shrimpers would haul in an incredible amount of shrimp. But nowadays, for the last 15 years or so, it hasn't been the same.

Aside from the black gill, which Gale said he believes is causing shrimp populations to decrease, he said that the climate is affecting the seasons for different types of shrimp. Where brown shrimp and white shrimp used to have distinct seasons, one disappearing almost entirely before the next arrived for the year, they now all meld together, and in turn Gale said it changes the prices that some shrimp, like brown shrimp, are going for on the market.

Black gill isn't killing the entire Georgia shrimp fishery outright, but it is having a drag on the resource, Frischer said.

There are still lots scientists are hoping to learn about the parasite, like how it survives and what it does before it finds a host shrimp and how to better forecast the severity of a black gill season given environmental indicators. But for now, the shareholder party agrees that communicating, observing and studying the parasite is what needs to be done to ensure the shrimp fishery resource is maintained for the future.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Georgia studies shrimp parasite hurting industry, shrimp population