Sidney, Monroe and Jerry: Conversations I wish I had with my dad about his views on race

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

I was 6-years-old, snuggled in my dad’s lap in the family station wagon parked at the drive-in on South 27th Street. My mom sat beside us on the front seat, and we passed a large bucket of salty, buttery popcorn and a giant, movie-sized box of Milk Duds back and forth, eagerly awaiting the dark so the movie could start. I’m fairly certain the rest of the family — my three older brothers and one younger sister — were crammed in the back seat, fighting over their own movie snacks, with one sibling (whomever lost at rock/paper/scissors) banished to the “way back,” as we called the tail-end of our wood-paneled station wagon. I assume the rest of the family was there that night, since it’s unimaginable that any one of them would’ve passed up a rare trip to the drive-in. But honestly, the recollection of my siblings’ presence is crowded out by the joyful memory of me being the chosen one that night, sitting there in my dad’s lap, my mom beside us, sharing treats.

I was reminded of this memory by the death of Sidney Poitier last year, because the movie we were there to see was Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, featuring Spencer Tracy in his final performance (he died shortly after production). Tracy stars as the husband of Katharine Hepburn, and Sidney Poitier plays as a Black man seeking to marry their white daughter.

I remember at first being confused by the movie. What was the big deal? The handsome man loved the pretty girl. Why didn’t the girl’s father like the handsome man? What was all the fuss about? As the film went on, the problem became obvious, even for a 6-year-old white girl raised in Greenfield, Wisconsin. As a kid growing up in the late ‘60s and ‘70s, seeing a person of color in Greenfield back then was rarer than an early and warm Wisconsin spring.

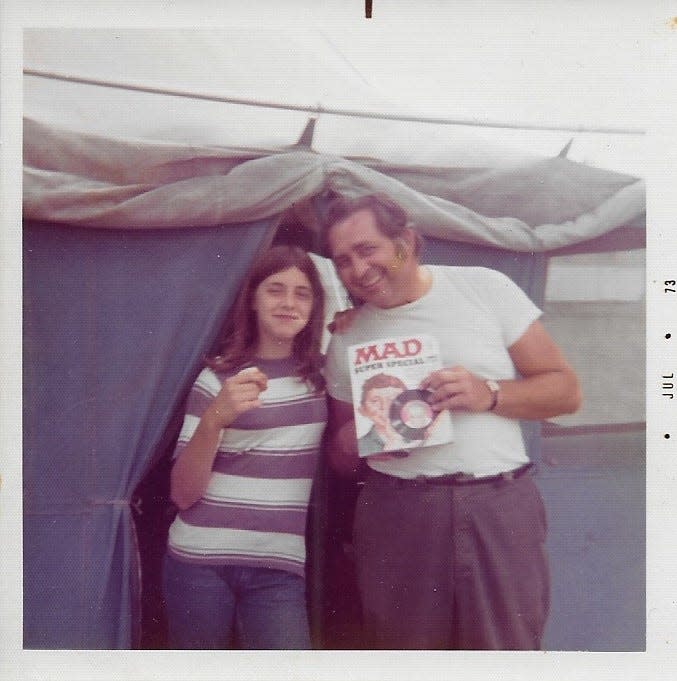

After the movie ended, Dad was oddly silent. Anyone who knew my dad, Jerry, also knew that the words “silent” and “Jerry” had never been used in the same sentence. I turned to him and placed my small hand on his stubbly chin. “Daddy,” I said, “would you let me marry a Black man?”

Dad looked as if I had punched him in the gut. He took a deep breath and then gazed out the driver-side window while my mom remained silent. After what felt like forever, he turned back to me.

“Well, if you loved him, I guess I would,” he said quietly.

A fishing trip and chance to see beyond his very white life

At the time, I had no idea how far the answer to my innocent question carried him from the Polish/German neighborhood on the lower south side of Milwaukee where he grew up and where people who were “different” than the Polish family, friends and co-workers he knew were few and far between. Like the Italian landlord of the duplex he and my mom lived in when two of brothers were toddlers.

It wasn’t only the movie that expanded his pale perspective and helped him see beyond his very white life. When I was a kid, my dad was an ambulance driver for Milwaukee County. One of his co-workers was a man named Monroe Dodd. Monroe was Black, which initially didn’t sit well with Dad. Would Monroe be lazy, as my dad had been taught all Black people were? Would Monroe try to steal from Dad’s locker, since family and friends had long warned him that Black people were thieves and couldn’t be trusted? Did Monroe get the job because it helped the county meet some quota? My dad had his suspicions, having heard that was why too many Blacks got jobs for which they weren’t qualified.

Turns out, none of my dad’s assumptions were realized. Just the opposite. Monroe turned out to be a hardworking and reliable co-worker and, like my dad, a loving father. But best of all, Monroe shared my dad’s passion for fishing. So when Monroe invited him on a fishing trip, Dad jumped at the chance.

I don’t think my dad realized when he said yes just how far they’d travel, figuratively and literally. Because on that trip, Monroe introduced Jerry to the Deep South, where Monroe grew up and where my dad, for the first time in his life, experienced what it was like to be a minority.

I don’t recall anything special about when he returned from that fishing trip. My oldest brother Mike remembers that Dad didn’t say much about it — again, a rarity for Jerry. But Mike says Dad did come back different, somehow. Less critical of “them.” Less willing to pile on when family and friends complained about “those Blacks.” What I do recall, that summer of 1967, was Father James Groppi, a priest and local activist, announcing a civil rights march across the 16th Street Viaduct located just blocks from where my dad grew up and my grandparents still lived. It was all anyone could talk about back then, even in front of us kids at the required Sunday dinners held at my grandparents’ house each week. I recall how angry and appalled my adult relatives seemed to be as the event drew near. A white Catholic priest leading a protest march? With Black people?

Read more about this period in Milwaukee history in 50-year ache

The 16th Street Viaduct was Milwaukee’s Mason-Dixon Line back then and unfortunately, in too many ways, it remains so. The viaduct, or bridge, separated Blacks crammed together on the dense north side of the city from whites, mostly Polish or German immigrants, who had claimed land on the more expansive south side after first arriving in the late 1800s. Locals called the viaduct “the longest bridge in the world” because it “connected Poland with Africa.” The march across it in 1967 was intended to highlight and protest the lack of fair and affordable housing for the city’s Black residents.

To hear my relatives discuss it that long-ago Sunday, Groppi was a disgrace to the priesthood for even suggesting that “they” move anywhere near “us,” no matter what the reason. The high rents paid by Blacks for duplexes neglected by white landlords (since building code violations were often ignored by local authorities) wasn’t the fault or responsibility of Milwaukee’s white community.

“Not our problem,” my relatives agreed. “They can just move back down south if they don’t like it here.”

Questions never asked about washing away stains of systemic racism

I remember my dad didn’t say much during the discussion. And I remember it being the first time I heard the “N” word, although it wasn’t my dad who said it. And while I recall that Dad didn’t challenge the relative who uttered the vile word, I know that we left my grandparents’ house shortly afterward.

The protest began on Aug. 29, 1967, my dad’s 38th birthday, marking the first of 200 consecutive marches for fair housing in Milwaukee. One year later, the Milwaukee Common Council finally passed fair housing laws, the marches inspiring a local movement for social and racial justice that continues in Milwaukee to his day. But beyond my city, the sad fact is, our entire country was built on a foundation of racism.

The South grew in power and wealth because of the free labor of enslaved Black people, with the rest of the U.S. greatly benefitting as well from the enforced labor of Blacks. After their emancipation, Black people, whose sweat and blood built this country, faced new challenges like laws denying them federal housing loans; dictating what schools they could and couldn’t send their children to; determining whether or not they could vote. Those laws, and others like them, were created to keep Black people down in the belief that if people of color succeeded, whites would somehow lose. To think that years of ingrained, systemic racism hasn’t left a mark that continues to stain us to this day is absurd. It certainly left a stain on my dad, and one that was tough to erase. An invitation to go fishing and a drive-in movie are what I believe began to wash it away.

My dad died more than twenty years ago, and I regret that we never spoke of these things. If he were here now, I’d ask Dad what he and Monroe talked about as they cast their lines into the fishing holes of the Deep South. I’d ask my dad if being in Monroe’s world might have made him less fearful, resentful and more open to someone with whom, at least at first, he thought he had very little in common. I’d ask what it was that changed him enough for his eldest son to notice a difference after he returned home. And I’d ask Dad what inspired him to give me the answer to a question I’m certain he never imagined, or hoped, his 6-year-old daughter would ask.

Jill J. Morin is an author, consultant, speaker and community activist. She’s the former executive officer, principal and director of Kahler Slater, an international architecture and design firm headquartered in Milwaukee. Her fiction work and personal/political essays can be found on her blog, Jillosophy (www.jilljmorin.com).

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Guess Who's Coming to Dinner sparked an innocent question to her dad