Sidney Poitier fought for his place in movie history, then transcended it

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Sidney Poitier, the actor whose groundbreaking movie roles in the 1950s and '60s opened doors for generations of Black performers and brought him a history-making Best Actor Academy Award for Lilies of the Field — the first ever given to a Black man — died Friday. He was 94.

For a movie actor, there is perhaps no crueler fate than to be forced to serve as a symbol from the first day you step in front of the cameras to the moment when, more than 50 years later, you give your final performance. Acting is about risk-taking, exploration, struggling all your life with how best to make vivid the humanity of the character you play, for better and for worse. It's hard, maybe even impossible, to do your job when the expectations of an entire industry, and of an entire race, are draped across your shoulders.

It is part of the lasting significance of Poitier that he took on a burden he never asked for not as a curse but as a responsibility, and bore it not with resentment but with unshowy solemnity. For the first 20 years of his movie career, which began with Joseph L. Mankiewicz's No Way Out in 1950 and ended with the TV movie The Last Brickmaker in America in 2001, Poitier was, as he often put it, "the only one" — the lone Black actor whom Hollywood allowed to carry a movie and knew would draw an audience, the only Black actor white audiences wanted to see, the only Black actor many African-American moviegoers knew existed. He began his career fully aware of his singular place in movie history. And then, year after year, in film after film, he both earned it and fought to transcend it.

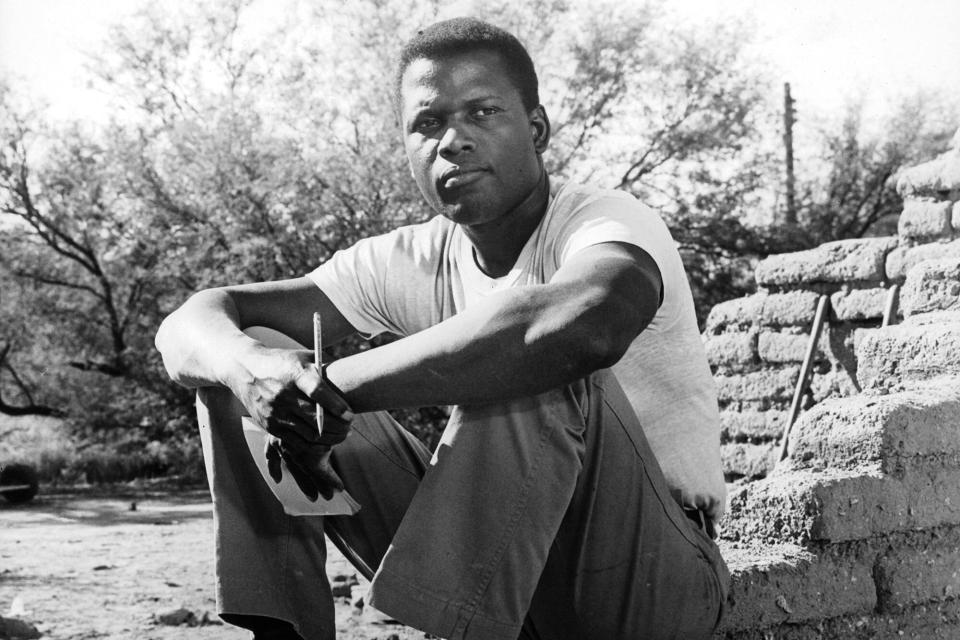

United Artists/Getty Images Sidney Poitier in 'Lilies of the Field'

The greatest tribute one can pay to Poitier may be to say that his passing does not leave a void. When he arrived in Hollywood, no Black man had ever been nominated for an Academy Award for acting (a barrier he shattered in 1958 with The Defiant Ones), let alone won the prize (that breakthrough came five years later, again courtesy of Poitier, in Lilies of the Field).

Today, for all of the legitimate criticism of underrepresentation in Hollywood, we are in a world Poitier helped us reach: We have Black blockbuster stars and Black directors and producers, Black character actors and Black leading men, and several Black Oscar winners who were not yet born when Poitier won the trophy. To some of the younger ones, his name, back in the news this week, must have felt remote, a reminder of a distant figure from another time. It's not just that Poitier crossed a bridge they never had to cross. It's that he became the bridge, connecting a Hollywood in which African Americans were consigned to playing sidekicks, stereotypes, and shuffling servants — "toms, coons, mulattoes, mammies, and bucks," as film historian Donald Bogle put it with brutal accuracy in the title of his seminal history of Black Hollywood — to an era in which those caricatures continue to give way, albeit with painful slowness, to a richer, deeper, more human variety of roles and, eventually, of opportunities.

If Poitier so often seemed in a class by himself, it's because he was, for much of his early life, an alien in both Black and white America. Raised in the Bahamas, he made his way to Florida and then to New York in the '40s, where opportunities for Black theater actors, though scarce, actually existed. He worked blue-collar jobs and drank in the thriving culture of Harlem while teaching himself unaccented stage diction by listening to a white man on the radio. He was soon on Broadway, receiving good reviews in a production of Lysistrata and drawing the attention of studio talent scouts.

"Back then," Poitier said later, "no route had been established for where I was hoping to go." So he forged his own path, breaking out with a role in the 1955 hit The Blackboard Jungle and then climbing the mountain to greater and greater recognition — in The Defiant Ones and Lilies of the Field, in A Patch of Blue and To Sir With Love, in Guess Who's Coming to Dinner and In the Heat of the Night. By the beginning of 1968, Poitier was drawing a salary of close to $1 million per film, almost (but not quite) as much as top-tier white actors, and was named the number one box-office star in America in a poll of motion picture exhibitors — another summit he was the first to reach.

Poitier's rise, though, came at a bitter price. He began his career, he said, feeling "that I could be as good an actor as Brando, as good as Monty Clift, as good as any American actor of substance." Could he have been? It's hard to say, since he worked in an industry that kept so many of the opportunities routinely afforded to his white contemporaries firmly beyond his reach, and Poitier, it must be said, chose to deprive himself of others. Famously, he refused to play bad guys, even those that would have allowed him to challenge himself and stretch his talent. Near the height of his success, he even turned down the chance to star in a film version of Othello, unwilling to risk playing a Black man inflamed by sexual jealousy over a white woman. "If the fabric of the society were different, I would scream to high heaven to play villains," he said at the time. "But…not when there is only one Negro actor working in films with any degree of consistency."

Within the constraints of the age and of his own beliefs, Poitier became an onscreen master of keeping everything under control, of bearing the belligerence and misunderstanding and suspicion aimed at him with a beautifully calibrated set of reactions that ranged from bemused good humor in comedies like Guess Who's Coming to Dinner to chilly hauteur, watchfulness, and quiet rage that was almost never allowed to boil over. When it finally did for In the Heat of the Night's Virgil Tibbs, Poitier dazzled audiences by showing that he could turn even a violent and long-withheld flash of temper on and off again while barely rumpling his suit jacket.

In the worst of his movies, sanctimonious parables of tolerance and understanding, he became what The New Yorker called the "caricature of a Negro as a Madison Avenue sort of Christian saint, selfless and well-groomed," not to mention all but neutered. But at his estimable best, Poitier — on screen and off — presented to both white and Black Americans a model of grace under pressure, someone whose very presence and composure on screen was in itself a reminder of what an imbalanced world he had to inhabit. It took extraordinary, and almost consistently underestimated, effort. "Sidney is the smoldering flame that you don't think will catch fire and burn down the house," his frequent costar Ruby Dee told an interviewer in 2000. "He has a capacity for explosion that is incredible. It takes possession of him." That is, when he allowed it to — which was rarely.

Nobody knew better than Poitier that exceptionalism had its perils. By the late '60s, when the civil rights movement had crested, the ghettos were burning, and the Vietnam War was galvanizing protesters and widening the generation gap, Poitier, just at the moment of his greatest acceptance in Middle America, started to feel the sting of rejection from a younger, more radicalized generation of African Americans. He was sneered at as a "million-dollar shoeshine boy" (and far worse) and written off as an Uncle Tom by young critics who were glibly dismissive of the challenges he had faced. Despite a long record of quiet civil rights activism, he was attacked for not being progressive enough, for not doing more to get work for other Black performers, even for marrying a white woman, Joanna Shimkus, after he and his first wife divorced (he was the father of six daughters). The treatment stung bitterly, especially since, as the critic Vincent Canby wrote perceptively in 1970, "Whether good or bad, almost every movie Sidney Poitier has made has been a kind of elegant sit-in, an act of conscience that has quite measurably increased the opportunities to all other Black actors."

So Poitier stepped away from his life as a performer. As he ceded the spotlight to superstars like Richard Pryor in the '70s, he turned to directing and producing, employing hundreds of African Americans on the films he made. He retreated to the Bahamas, and to his family. He became an accomplished memoirist, an ambassador, and, for long stretches, an invisible man, a kind of abstraction so mythic that his very identity became the subject of a prize-winning play, John Guare's Six Degrees of Separation, in which he never even appeared as a character.

When he finally returned to movies in 1988, after more than a decade off camera, it was almost a relief to discover that Poitier was not a concept or an ideal or a monument, but an actor — one who, starting his seventh decade, had made his peace with the injustices done to him and decided that he wanted to spend the rest of his career doing the work he had set out to do as a young man. This time — thanks largely to his own efforts — he had plenty of competition for great roles, and he didn't always find or choose the best ones.

It didn't matter; his legacy was secured every time a Black actor stepped in front of a camera without having to question whether they belonged there. If the last years of Sidney Poitier's life sometimes felt like an extended victory lap, it couldn't have been bestowed on a more deserving man. Forty years after earning his Lilies of the Field Oscar, he was given an honorary Academy Award for his achievements "as an artist and a human being." That same night, after too long a wait, Denzel Washington became the second Black man to win a Best Actor Oscar. Soon after, there was a third, and a fourth, and the achievement became unexceptional. Poitier could not have asked or hoped for more — nor, by carrying the banner for change for so long, so stoically, and with so little company, could he ever have done a greater service to those who followed him.

"I'll always be chasing you, Sidney," said Washington that night, speaking for more than one generation. "I'll always be following in your footsteps. There's nothing I would rather do, sir — nothing I would rather do."

Related content: