Sidney Poitier was more than a symbol. He was one of the great movie stars, full stop

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

To celebrate an actor of Sidney Poitier’s greatness should require no qualifier, no asterisk, though before he died Thursday at the age of 94, a lot of people seemed eager to affix one.

Poitier was the first Black man to win an Academy Award for best actor, a blazer of representational trails that forever reshaped the landscape of American culture. His image exploded the world’s notions of whose stories were worthy of attention, whose presence could fill a theater, who could be called a movie star. Had this Miami-born son of Bahamian tomato farmers never stumbled his way into a brilliant stage and screen career, the significantly more diverse landscape of American acting before us today — the landscape of Denzel Washington and Viola Davis and Jamie Foxx and Octavia Spencer and Mahershala Ali, to name just a few of Poitier’s fellow Oscar winners — might look markedly different.

But for too long a time, Sidney Poitier stood alone. And as he knew all too well, exceptionalism could be more burden than blessing. Even during his rise to fame in the late ’50s and ’60s, his career was held up as a record of limitations as well as triumphs. Too often, his critics noted, Poitier was cast as a pillar of rectitude, a figure of unimpeachable morals and manners who could gently counter — by to some extent accommodating — the virulent racism of white America. He was criticized for locking himself, or allowing himself to be locked, into the role of the upstanding Black man, who confronts even the worst bigotry with impossible poise, elegant diction and a coolly measured anger that he was always careful to restrain.

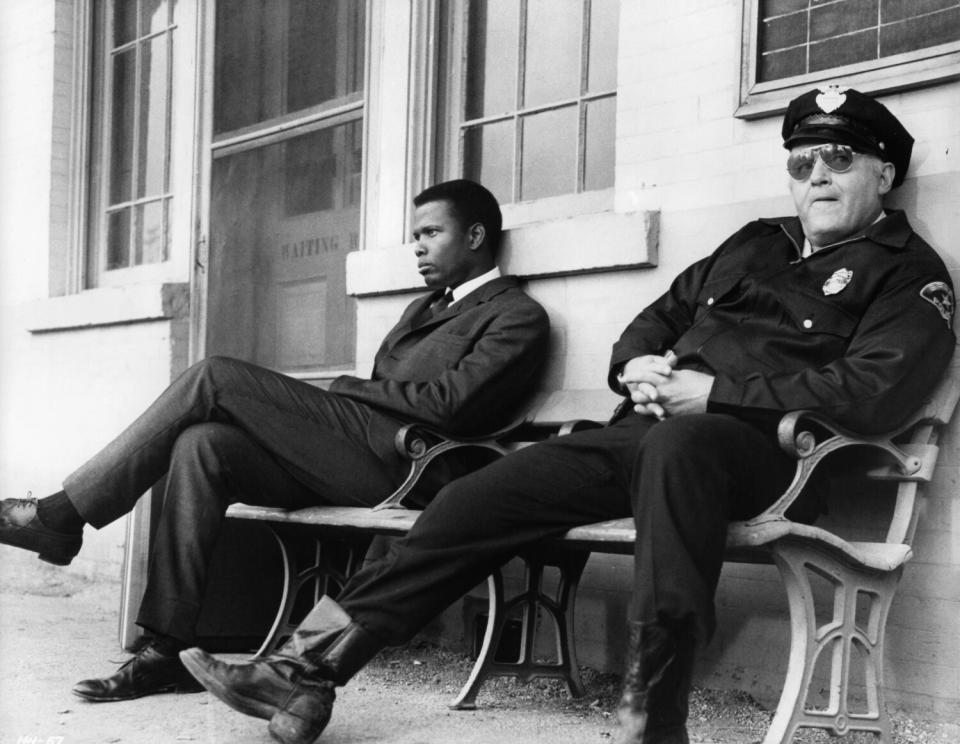

That anger could spill out, of course, and when it did, the effect was volcanic. Perhaps the most forceful example comes courtesy of Norman Jewison’s “In the Heat of the Night” (1967), when Virgil Tibbs, the police detective who would become one of Poitier’s most famous roles, returns a white racist’s slap in the face. It’s a still-electrifying moment, the kind that can throw an entire career into sharp relief. (It’s also a moment that Poitier himself suggested; in the original version of the script, Mr. Tibbs simply walked out.) But for many, including those who wanted Poitier to move in more confrontational directions, it wasn’t enough. In their eyes, the other star-making vehicles of Poitier’s ’60s heyday were liberal message movies aimed at soothing the brows of a mostly white audience.

He was the schoolteacher who irresistibly whips a class of rough-edged London teenagers into shape in “To Sir, With Love” (1967). He was the outsider unthreatening enough to win over his white fiancée’s parents in 1968’s “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.” He could be a sacrificial lamb in dramas like “Edge of the City” (1957), as a dockworker who pays the ultimate price for the lowly drifter (John Cassavetes) who joins his crew. And the wanderer who finds himself waylaid, exploited and gradually charmed by German nuns in “Lilies of the Field” (1963), which earned Poitier that landmark Oscar. By that point he had already been nominated for 1958’s “The Defiant Ones” alongside his co-star, Tony Curtis; the movie, in which the two play a pair of cuffed-together prison escapees, suggests a metaphor for the shackles that, for his harshest critics, Poitier never took off.

Poitier knew those limitations better than anyone. And he found workarounds later in his career, especially by writing and directing his own films, starting with 1972’s “Buck and the Preacher,” in which he and longtime friends Harry Belafonte and Ruby Dee turned an entire history of deracinated American westerns on its head. But it took Poitier years to achieve that degree of creative control.

Earlier in his career, to protect his role in “The Defiant Ones,” he grudgingly agreed to play Porgy in Samuel Goldwyn’s 1959 film of “Porgy and Bess,” a part that Belafonte had turned down. Poitier often lamented how frequently he played heroes and how rarely he played villains (one exception being the 1964 adventure saga “The Long Ships”). Rarely were his characters allowed to express sexual desire on screen (or to be objects of desire in turn), as evidenced by pictures like 1965’s “A Patch of Blue,” considered groundbreaking at the time for its depiction of an interracial romance.

As the film journalist Mark Harris wrote in his book “Pictures at a Revolution,” Poitier “demonstrated a remarkable instinct for self-presentation; without anyone to emulate, he knew exactly how much he could say publicly without jeopardizing his status in either black or white America.” What seems like deftness and nuance in one era, of course, can come across as timidity in another. Seen through the lens of today, with so many more examples of Black representation thankfully available, Poitier’s achievements have grown easy to dismiss as quaint relics of a less progressive era.

That assessment feels both uncharitable and more than a little self-flattering, and it reveals less about Poitier, I think, than about those who believe theirs to be the most morally courageous, politically enlightened generation that has ever existed. Certainly it says little about the emotion that Poitier’s body of work still generates, or the truths of which it still reminds us: namely, that a performance is more than a role description, and that great acting creates its own irreducible, uncategorizable energy. Poitier’s body of work is often spoken of, both rightly and reductively, as a series of historic firsts. But it also endures — gloriously, abundantly, inexhaustibly — as a wellspring of cinematic pleasure.

Poitier may have played his share of symbols, but you’d rarely catch him playing a cipher. His presence was too enormous for that, his gaze too easy to get lost in, his Bahamian-accented intonations too distinctive. One of his first screen performances, in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s “No Way Out” (1950), remains a personal favorite: In that nerve-jangling thriller, he plays a county hospital doctor who gets caught up in a maelstrom of criminal violence when he’s wrongly blamed for the death of a patient under his care.

The story sounds like a template for many that would follow, including “In the Heat of the Night,” another story of a Black man whose professional authority threatens the dumber, meaner white men in his midst. But Poitier’s mesmerizing performance in “No Way Out”— it takes talent and nerve to stare down Richard Widmark — never feels like a formulaic construct. It’s full of repressed pain, controlled fury and a wholly understandable, deeply human fear. It also showed, even at that early stage of his career, a leading man’s fully formed charisma.

That charisma would serve him well in pictures like “A Raisin in the Sun,” the 1961 film of Lorraine Hansberry’s great play, in which he reprised a role that he had played on Broadway. As Walter Lee Younger, the passionate son, husband and father striving for better for himself and his poor Chicago family, Poitier is remarkable; the goodness that he famously exemplified is still there, but it commingles with flashes of fury, frustration, self-doubt and even self-loathing. It stands as an early rebuke to the notion of Poitier as some kind of benevolent Black balm for white souls — something that could also be said of his star-making turn in “Blackboard Jungle” (1955), in which he essentially played the juvenile-delinquent flip side of his future role in “To Sir, With Love.” Or perhaps “A Band of Angels” (1957), a less fondly remembered drama in which Poitier nonetheless stands out as an enslaved man in the American South, speaking of — and at one point acting on — his violent rage against his white oppressors.

That rage wasn’t entirely an act. “I’ve learned that I must find positive outlets for anger or it will destroy me,” Poitier wrote in his 2000 autobiography, “The Measure of a Man,” reminiscing on the racism and injustice he’d both experienced and witnessed during some of his childhood trips from the Bahamas to Florida. “There is a certain anger; it reaches such intensity that to express it fully would require homicidal rage — self-destructive, destroy-the-world rage — and its flame burns because the world is so unjust. I have to try to find a way to channel that anger to the positive, and the highest positive is forgiveness.”

It would be reductive to suggest that Poitier’s career was some triumph of positivity over rage, or that he took an easy, forgiving attitude toward the industry that slowly and grudgingly made room for him. But what he wrote does explain some of the rich, complicated emotional and psychological layers you see in a Poitier performance. The anger is often there, but it isn’t all that’s there. Often it’s held in check by other qualities: playfulness, knowingness, sardonic wit, plaintive sorrow, a joy in being alive.

Consider “Lilies of the Field,” a movie that plays today as both creaky and charming. It steals its way into my thoughts surprisingly often, less for its righteous message of brotherhood (or sisterhood) than for the mid-movie sequence in which Poitier’s Homer Smith first leads the nuns in a performance of the gospel song “Amen.” The sequence is designed to relieve the cross-cultural tension that’s been building through the movie all along, though you could divorce it from its narrative context entirely and still be delighted by it.

There’s so much exuberance in the way Homer conducts his amateur choir, setting and sometimes resetting their tempo. He sticks out his chest and pumps his arms. His voice becomes a whisper, then rises again in a “Hallelujah!” crescendo. His gusto feels entirely instinctual.

Poitier seems to lose himself in this moment, and maybe he did and maybe he didn’t; he was a great enough actor to keep you from telling the difference. Either way, that moment is joyous in its feeling and unconstrained physicality. This was the kind of movie Poitier’s critics dismissed as hopelessly retrograde, a trap for a legend who deserved better. But look at it from a different angle, the angle that Poitier strived throughout his career to show us, and what you see looks an awful lot like freedom.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.