Sikh activist death has echoes of Litvinenko case, says lawyer in both cases

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The mysterious death of a Sikh activist on British soil has echoes of the Litvinenko poisoning, according to a lawyer involved in both cases.

Michael Polak, a human rights barrister, has written to James Cleverly, the Home Secretary, demanding a full investigation into the sudden death of Avtar Singh Khanda in Birmingham in 2023.

His official cause of death was acute myeloid leukaemia, a finding backed by West Midlands Police.

However, Mr Polak, who worked on the murder of Russian dissident Alexander Litvinenko, believes it is “more likely than unlikely” that Khanda, 35, was a victim of foul play.

He claims detectives at West Midlands Police, which is in “special measures” following a series of failings including poor investigations, did not conduct even the most basic inquiries into the case.

He added that the young activist may have been exposed to lethal radiation as part of an alleged operation to eliminate “enemies” of the Indian state.

“It is possible we are looking at Litvinenko Part II. There are parallels between it,” Mr Polak said.

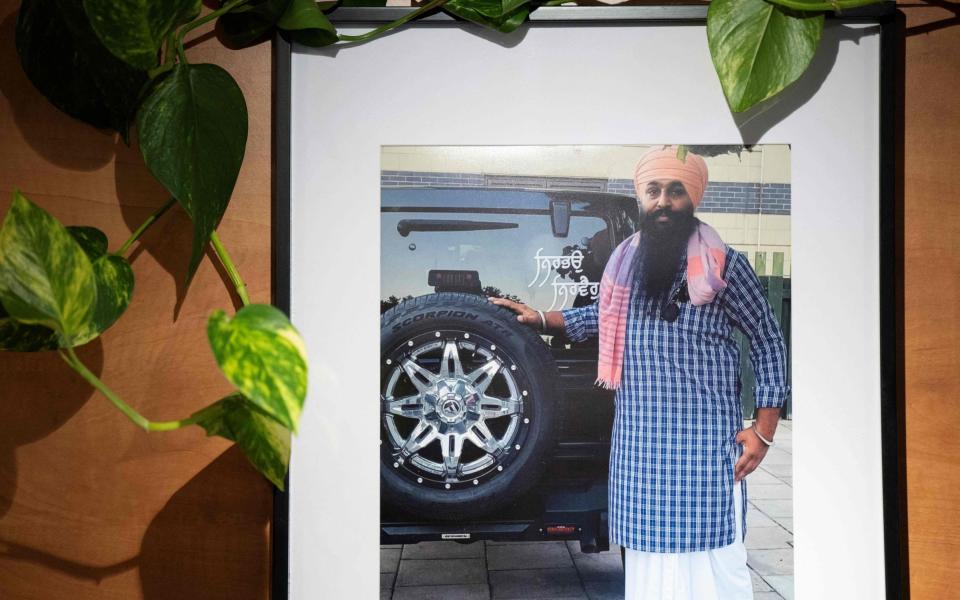

Khanda moved to the UK in 2013 and was a prominent supporter of the so-called Khalistan movement to establish a separate homeland for Sikhs.

Narendra Modi, India’s Hindu nationalist leader, regards the campaign as a serious security threat and has vowed to crack down on key figures.

Shortly before his death, Khanda’s name had appeared on a “hit list” of 20 overseas political activists wanted by Indian security services. He became critically ill days before the assassination of another Sikh political activist in Canada.

The murder of Hardeep Singh Nijjar in British Columbia caused a major diplomatic crisis after Justin Trudeau, the Prime Minister, pointed the finger at President Modi. Shortly afterwards, the FBI intercepted a plot to kill another Sikh activist, Gurpatwant Singh Pannun in New York.

Questions are now mounting over whether India’s security services could have been behind Khanda’s unexpected death.

Until his hospitalisation in June, Khanda had no record whatsoever of ill health.

Friends say he was so fit and healthy that he was not even registered with a doctor.

He did, however, have other worries. Just a month before his death, he posted a disturbing video on his Facebook account, claiming he and his family were being threatened by India’s security services.

Looking anxious and gaunt, the 35-year-old claimed Indian police had been harassing his mother and sister in Punjab, frog-marching them out of their home for repeated interrogations.

‘Enemy of the state’

“Now they’re pressuring me,” Khanda added, saying he was getting “call after call from different police stations” in India. As the video went on, he sounded increasingly desperate and fearful, saying nobody was helping him.

“Now we have just appealed to God. Only he will bring us out of this difficult time,” he said.

Khanda’s cri de coeur might seem a little paranoid. After all, foreign intelligence services are acutely aware of the risks associated with harming individuals overseas. The murder of Litvinenko in 2006 using a highly radioactive substance called polonium, plunged UK relations with Russia into a deep freeze for years.

Nonetheless, after being identified on Indian media channels as an “enemy of the state,” Khanda – who had no criminal record – had good reason to be alarmed.

Around the time he posted the video, a pro-Modi Indian TV channel broadcast a sinister warning to Sikh political activists “hiding abroad” that Indian intelligence agents would hunt them down and “take action” against them “one by one”.

Aaj Tak, a leading Hindi news channel, published pictures of all 20 “most wanted” men, along with their likely whereabouts. Six lived in the UK. In January, it emerged that the UK Government has issued “threat to life” notices to several British Sikhs.

Three weeks earlier, Khanda had attracted the attention of India’s security services after attending a rally outside the Indian High Commission in London.

At some point during the protest, the Indian flag was torn down, an act for which he was blamed on Indian social media.

According to his friends (who insist he had nothing to do with the flag incident), India’s equivalent of MI6, known as RAW, also mistakenly thought he knew the whereabouts of another activist on their “wanted” list named Amritpal Singh.

He was now firmly on their radar – and feeling the effects.

“He was hugely stressed and distressed at this time – massively,” according to his friend Jas Singh, a management consultant and Sikh activist.

“The threats were everywhere. I asked him if he was okay and pushed him to let me know, but he was a strong lad, and had full faith in God that truth would prevail.”

Khanda’s friends and fellow political activists urged him to record everything. He shared audio recordings with them, including an intimidating phone call from a female police officer.

‘You know what we’re capable of’

“She was saying: ‘Tell us where Amritpal is. Otherwise you know what we’re capable of,’” according to Jas Singh.

On Saturday, June 10, 2023, Khanda, who worked as a part-time presenter at a Sikh satellite TV channel at weekends, began feeling unwell. The following day, he was worse, complaining of a sore stomach and a painful leg. Soon he was in agony, and an ambulance was called.

“We thought he’d soon be back! Nobody had any serious concerns,” said Jas Singh, who had been out with him only a few days earlier, when he had seemed perfectly healthy.

After being admitted to Birmingham City Hospital, Khanda was diagnosed with AML, a type of blood cancer which causes clotting. According to the NHS website, the disease has been linked to radiation.

As he lay in hospital fighting for his life, rumours that he had been fatally poisoned were already circulating on Indian social media. In posts falsely labelling him a “terrorist,” supporters of Modi’s regime appear to be celebrating his demise, with one calling it “karma”.

The first report that he was on “life support” having been “suspectedly poisoned in the UK” appeared at 2.54pm on June 14, a day before he died on social media.

“How did they know he was even ill? Their narrative was, ‘We’ve got our guy! This is what you get! If you mess with our flag; we’ll kill you’. This is their actual language,” said Jas Singh.

Events after Khanda’s death fuelled suspicions of foul play. In cases of sudden and unexpected deaths, it is routine to carry out a post-mortem to establish the cause.

No autopsy was conducted on Khanda’s body because doctors were satisfied that he had died of AML. The coroner agreed.

Michael Polak believes those responsible for the decision may been missing the point.

“If Mr Khanda was poisoned, it’s more than likely he was poisoned outside the hospital and they didn’t know what they were looking for. At that stage, nobody was thinking about Sikhs in Britain being targeted by poisoning.

“If it were a Russian in Fulham or something like that, then the first thing they’d think to check would be poisoning.

Mr Polak added: “Often with medical conditions people get the wrong end of the stick and say, well, it’s acute myeloid leukaemia. Yes, well, how did he get it and why did he get it so quickly? That’s the kind of next level of questioning that ultimately needs to be considered.”

In another unusual feature of the case, the family and their representatives were repeatedly denied access to the body.

Handling of Khanda’s remains ‘was bizarre’

M Singh, the funeral director appointed by the family, who did not wish to give his full name, describes the handling of Khanda’s remains as “bizarre to say the least.”

“I’ve never experienced it, and we manage a thousand funerals a year,” he said.

The undertaker claims that he was initially informed by the hospital that the body was “in a locked fridge, in a sealed bag, as part of a police investigation”.

“Generally, obviously we would have access to the deceased and we only wouldn’t if there was something serious going on, so we were under the assumption that there was a police investigation, but frankly there wasn’t. So that was a bit alarming; a bit strange. We were speaking to other departments about the possibility of a private post-mortem.

“They were at first happy to do so. Then they came back to us saying, ‘actually, sorry, we can’t do this; we don’t want to disclose why; but it’s not a case that we want to touch, because we’ve been told by higher up’. And it’s like, who’s higher up? What are you on about? It was very very strange.”

The Sandwell and West Birmingham NHS Trusts did not respond to a request for comment.

Friends and family also want to get to the bottom of the sudden departure of an Indian official from the High Commission in London, who they claim is a RAW agent.

The alleged operative left a few weeks after Khanda’s death, raising suspicions that he was withdrawn at the request of the UK.

In a letter to Caroline Nokes, a Tory MP, in January, security minister Tom Tugendhat refused to comment on suggestions the agent was “expelled”.

Of course, there may be nothing more to Khanda’s death than meets the eye. Perhaps his sallow appearance in his haunting Facebook video is a sign that he was already suffering from AML, brought on by entirely natural causes. Yet Mr Polak is unconvinced.

“In my opinion, given the timings of everything; given his position in the separatist Sikh community; it’s more likely to have been unnatural than it is to be natural.

“It would be a very strange chance that it happened three days before Mr Nijjar was shot down in Canada and in the same week that India arranged the attempted assassination of Mr Pannun in the USA,” he said.

West Midlands Police told The Telegraph that “our investigation concluded that this was a natural death and not suspicious”.

Asked why they had not spoken to Khanda’s friends or colleagues, they said that they were working “on behalf of the coroner who was notified of his death from the medical team that treated him. They confirmed a sudden death due to an existing illness”.