Silenced Florida voters: Races for Congress, Legislature decided before voting even begins

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

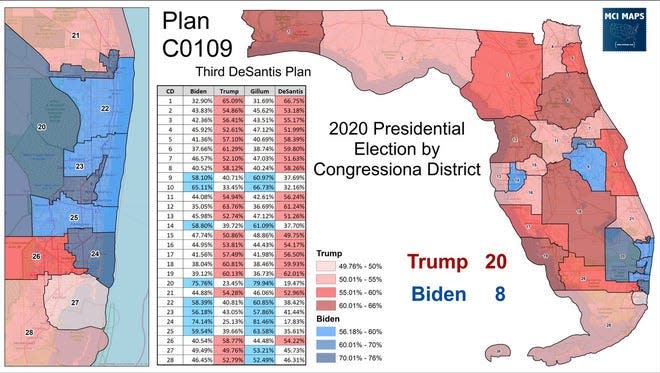

TALLAHASSEE — Even before any one of millions of Floridians casts a vote in this fall’s pivotal congressional elections, the outcome is almost a foregone conclusion.

In the race to represent Floridians in Congress, only two of 28 contests — at least on paper — appear competitive: District 27 in Miami-Dade County and District 15, in Polk, Pasco and Hillsborough counties.

Most of the other districts heavily favor Republicans, with a handful of remaining districts dominated by Democrats.

But it’s not just the congressional map that decidedly tilts Republican red.

Freshly drawn boundaries for state House and Senate districts also leave little doubt that Republicans will continue to hold sizable majorities at the state Capitol.

Following August's primaries, two dozen winners in state Senate and House races now are either unopposed or face longshot write-in opponents in November, while another 40 legislative candidates faced no opposition at all this year.

In the 40-member Senate, 16 seats are already decided, along with 48 of the 120 House seats.

Analysts say once-a-decade redistricting, steered by Gov. Ron DeSantis through a compliant, Republican-controlled Legislature, is contributing to a more politically polarized Florida voting public, with millions of Florida voters in districts now purposely shaped to hold massive numbers of voters from a single party.

These districts, with more than 60%, 70% or even 80% of voters historically favoring one party, serve to deepen the state’s divide, analysts said.

“Florida is certainly a competitive enough state that you could have more toss-up districts than you’re going to have now,” said Kyle Kondik, a campaigns and elections analyst with the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics.

In the 40-member state Senate, only four districts look like potential political toss-ups, races that have been decided by margins of 5% or less.

In the 120-member House, only 14 districts fall within those margins.

All told, only 20 congressional and legislative seats are potentially in play this year based on voting trends, marking a drop from 27 possible toss-ups under boundaries in place before this year’s redistricting.

In congressional races, the only real contests — again, on paper — look like CD-27, where Republican U.S. Rep. Maria Elvira Salazar faces Democrat Annette Taddeo, a state senator, and CD-15, where former Secretary of State Laurel Lee, a Republican, is vying with Democrat Alan Cohn, a former TV reporter, in November.

GOP Legislature went along with DeSantis: Senate bows to DeSantis with map boosting GOP at expense of Black Democrats

Ready for court fight: Ron DeSantis eyes court fight over Florida congressional map to reduce minority seats

DeSantis reworks history: Special session: Florida lawmakers heeding Gov. DeSantis' demand for new congressional map, enraging opponents

Kondik, managing editor of Sabato’s Crystal Ball political newsletter, acknowledged the state is clearly split between a red North Florida and a blue South Florida, making competitive districts tough to achieve but also leaving millions of voters on the electoral sidelines.

Some voters feel silenced in districts

Political maneuvering by Republicans in charge of state government has combined with population shifts to leave some voters feeling their voice is all but silenced in areas where their opposite party holds outsized numbers.

In some districts, at least a few Floridians are left wondering whether it’s even worth voting.

“People like me can become disenchanted, and angry,” said Judy Riley, 77, of Niceville, a Democrat, and past president of the Democratic Women’s Club of Okaloosa County in the Florida Panhandle, one of the most Republican regions of the state.

“But our job as the minority party is to let people know there are options,” she added. “They don’t like the lack of choices they see and the lack of having elected officials in Congress and the state House and Senate who share what they value.

“But you can’t give up,” Riley added. “You can only eat an elephant one bite at a time, as the saying goes.”

There’s also self-sorting going on, said Susan MacManus, a professor emerita in political science at the University of South Florida.

“People when they move to Florida from another state, or even within this state, they’re increasingly choosing the community they’ll live in based on its political leaning,” MacManus said. “You’re seeing this self-selection on party lines and economic lines, which can play into a community’s politics.”

A new study by the Leroy Collins Institute affirms the emergence of two Floridas.

The institute’s analysis of the 2020 presidential election showed 73% of Florida counties are “landslide” counties, where the gap between votes for former Republican President Donald Trump and Biden, the Democrat, was larger than 20%.

The study showed 12 Florida counties voted for Biden — five of them by a landslide. Fifty-five counties voted for Trump, 44 of them by a margin greater than 20%.

The divide also appears entrenched.

Another analysis of the 2020 presidential race found that voters in just four of 67 Florida counties “pivoted” between Democratic or Republican presidential candidates.

Ballotpedia defined these pivot counties as ones that voted for Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012, then voted for Trump in 2016. In 2020, St. Lucie, Jefferson and Monroe counties stayed with Trump, while Pinellas “boomeranged” to Biden, the Democrat.

Florida’s divided geography, a factor

Academic research, submitted in support of the Republican side during the lengthy court fight that followed the last round of redistricting a decade ago, also claimed that where Democrats and Republicans choose to live makes it natural for maps to favor the GOP.

Similar to patterns seen nationally, Florida Democrats are highly concentrated in the state’s urban areas, while Republicans are spread further. Because Florida law requires that districts be compact and contiguous, boundaries tend to pack in voters of one party.

Even though statewide voter registration is tight — with Republicans leading Democrats by a mere 36% to 35%, the GOP already holds a large majority within the congressional delegation and both chambers of the Legislature. No-party-affiliated Floridians count for 27% of voters.

Despite the lack of competition in local races, Florida also is home to drum-tight statewide elections, where it does seem every vote counts.

In 2018, Florida had an unprecedented three statewide recounts, with DeSantis and U.S. Sen. Rick Scott, both Republicans, and Democratic Agriculture Commissioner Nikki Fried, all winning by wafer-thin margins.

In November, DeSantis’ re-election bid against Democrat Charlie Crist is drawing much of the state’s political attention, along with Republican U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio seeking a third term against Democrat Val Demings.

Florida Republicans in the past year have grabbed a lead for the first time in modern history among registered voters — the GOP now outdistances Democrats by almost 270,000 voters. But the state’s local political boundaries can still leave some of these party members feeling adrift.

Mary Dobrow, a retiree in Pahokee, in far western Palm Beach County, is a Republican living in the most Democratic congressional district in the state.

With a Black voting population of almost 50%, District 20 is represented by U.S. Rep. Sheila Cherfilus-McCormick, D-Miramar, who won a special election earlier this year to replace longtime U.S. Rep. Alcee Hastings, D-Delray Beach, who died in April.

About 60% of the district’s 450,000 registered voters are Democrats.

“In any local election, most of the time, my vote doesn’t count much,” Dobrow said. “I think we need to get Republicans in office. But the numbers just are not there.

“Still, I do feel motivated to vote, because of the state impact. You’ve got to vote and, you know, one day, we’ll get lucky locally,” she added.

DeSantis defied constitution, court said

DeSantis took extraordinary steps — which a court found unconstitutional — to increase the number of Republicans Floridians will likely to send to Congress this fall.

He vetoed the approach taken by the Republican-led Legislature that would’ve positioned the GOP to win 18 of the state’s 28 congressional seats.

Republicans currently hold a 16-11 seat edge in Congress from Florida, with the state picking up an additional seat this year because of population gains in the 2020 Census.

DeSantis, though, wasn’t satisfied with a modest gain, and wanted more.

He successfully pushed lawmakers to endorse his plan to create 20 Republican-leaning seats, by strengthening GOP vote share in several districts and eliminating a North Florida seat held since 2017 by U.S. Rep. Al Lawson, a Black Democrat from Tallahassee.

Leon County Circuit Judge J. Layne Smith, a DeSantis appointee, overturned the map dismantling Lawson’s district, which also scattered 370,000 North Florida Black voters among four, Republican-leaning districts.

Smith ruled the plan violated the state’s voter-approved Fair Districts constitutional amendments, which prohibit the creation of district boundaries that diminish the ability of minorities to elect a candidate of their choice.

Still, the discredited map will stay in place for this fall’s elections, while the state appeals.

Governor helps with GOP priority

With Republicans focused on regaining a majority in Congress this fall, DeSantis has achieved a party priority, most likely adding four new Republican seats from Florida.

“One of the things a party does when it gerrymanders is it maximizes the number of safe seats for itself and minimizes the number of safe seats for the other side,” said Kondik, the UVA analyst. “But in making their own seats safe, they can make seats for the other side safer.”

That’s what Florida is now experiencing, experts said. More voters are being packed into districts where one party is dominant.

In case you missed it: Pete Antonacci, veteran top state government leader and director of Florida's election crimes unit, dies

More: Lone TV debate between Gov. Ron DeSantis and Charlie Crist postponed by Hurricane Ian

“We’re seeing swing counties disappear in Florida,” said Matt Isbell, an elections data consultant who works for Democrats. “That’s going to bleed into how districts are drawn, no matter who’s drawing them or what their intentions are. But we’ve also seen a lot of creative line-drawing, too, from Republicans this go-around.”

Isbell said demographic changes are altering the politics of large swaths of Florida. At least one outcome is clear, he added.

“Don’t expect the political polarization to change,” he said. “Not this year.”

Competition, not required

The Fair Districts amendments approved by Florida voters a dozen years ago were aimed at prohibiting lawmakers from drawing district boundaries that help or hurt a political party or incumbents.

But they didn’t address making districts competitive.

“The idea was to stop politicians from rigging districts to favor themselves and their party, and to protect minority voters. Those were the primary goals,” said Ellen Friedin, who led the ballot campaign in 2010. “But nothing in the amendment requires competitive districts.”

Indeed, across the nation, only Arizona, Colorado and Washington have standards that encourage district boundaries that foster competition in a general election.

Kevin Cooper, a Republican activist from Aventura, in Miami-Dade County, lives and votes in a district where Biden claimed almost 75% of the vote.

But he said that Florida’s political history keeps him going to the polls. Cooper looks to the 2000 presidential election, when George W. Bush won the White House only after winning Florida by 537 votes.

“Ever since 2000, it’s an old tale we tell each other in Florida. Yeah, our votes still do count here,” Cooper said.

John Kennedy is a reporter in the USA TODAY Network’s Florida Capital Bureau. He can be reached at jkennedy2@gannett.com, or on Twitter at @JKennedyReport

This article originally appeared on Tallahassee Democrat: Few competitive races for Congress, Florida statehouse silences voters