Silent Plains: With a history of neglect, grasslands have become the forgotten ecosystem

Nestled away from encroaching urbanization and expanding development, the sprawling grasslands at Lubbock Lake Landmark stand as a poignant reminder of the boundless beauty that once blanketed the Great Plains.

Characterized by its golden hue and vibrant collection of wildflowers, the local prairie is one of the few remaining sanctuaries of its kind in West Texas — mirroring the broader picture of the nation’s disappearing grasslands. The ecological biome that once claimed the greatest territory across the United States is now a vanishing treasure, dwindling in size with each passing day.

For many experts, the picture's clear: Grasslands have become North America's forgotten ecosystem.

Since the removal of Indigenous populations in the 1800s and their more gentle land management practices, North Americans have historically overlooked the significance of grasslands — seeing them as the equivalent to a blank slate — which equally provide as many ecological services as tree-dense rainforests and lively coral reefs, and are disappearing even quicker.

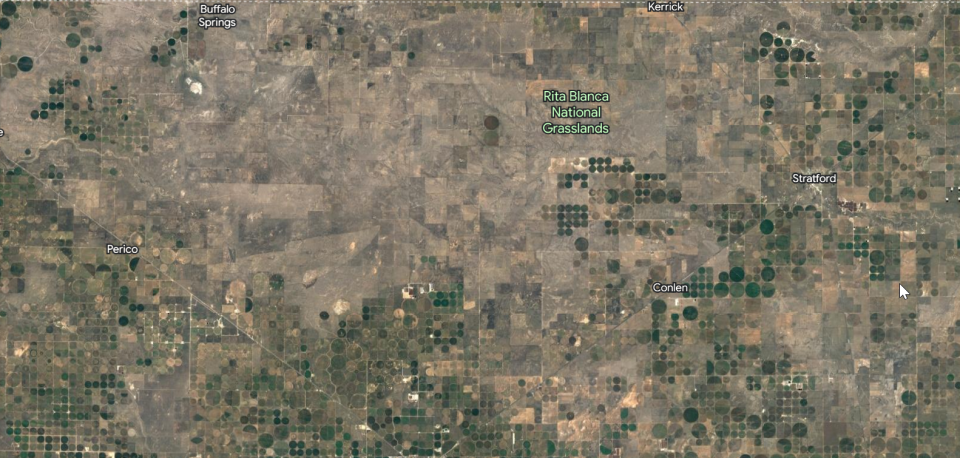

Centuries of farming and ranching operations, and more recently, energy development and suburban sprawl, have further pushed aside the priorities of grassland protections and conservation, posing a biodiversity crisis in one of the most valuable ecosystems on the planet.

“The Panhandle Plains is forgotten so much," said Kippra Hopper, a lifelong resident of the High Plains region and former president of the South Plains Chapter of Texas Master Naturalists. "Even by those who are involved in the environmental movement."

She hopes to see that change before it’s too late.

North America's forgotten ecosystem

Under the pressure of longstanding neglect, grasslands are among the most imperiled ecosystems on the planet. Yet, for decades, scientists and activists have favored protections of other biomes far more vocally.

Due in part to the political atmosphere surrounding the majority Great Plains — predominantly Republican and known for being leery of conservation policies — and the longstanding reverence toward agriculture in the region, most of the reasoning behind the phenomenon is public misperception, said Russell Martin, a wildlife diversity biologist for the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Frankly, grasslands don’t bear the same idyllic essence of nature’s most loved landscapes, like Colorado’s mountains or California’s coastlines, he pointed out.

“When the layman looks across the prairie, they just see a bunch of grass,” Martin said. “But, when someone who takes the time to learn how to identify all the grasses and wildflowers and species it embraces, it’s almost overwhelming how much is out there and how diverse that sea of grass actually is. If people could connect and learn about the ecosystem around them, they would really start seeing the beauty of the place we live in.

“It really is something, and you really can fall in love with it,” he added.

Grasslands are also up against the widespread misconception that trees and forests are the only sources for carbon sequestration (the process of capturing and storing the atmosphere’s carbon dioxide), bolstering the idea that grasslands are nothing more than a barren landscape. But Jon Hayes, vice president and executive director for Audubon Southwest, said that couldn’t be further from the truth.

After spending years also working for Texas Parks and Wildlife Department and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Hayes has cultivated a rare appreciation for the life and services that grasslands support.

“I think there is this current bias — especially in the climate world, because most people have a pretty simplistic understanding of carbon sequestration — and they all think that trees are the answer to that,” Hayes said. “We, in the environmental movement, for 20 years preached the seriousness of deforestation and clearing the rainforests, which isn’t wrong, but it’s almost like people learned the wrong lesson.

“Yeah, trees should be saved at all costs, but only in the places where trees are supposed to be. And the prairies aren’t meant to have trees,” he added.

Now after decades of abandonment, fewer than 40 percent of North America’s 550 million acres of historical grasslands — stretching from Alberta, Canada to Mexico — remain intact today, according to the North American Grassland and Birds Report by the National Audubon Society, a nonprofit organization that prioritizes the conservation of wildlife bird species.

In Texas, the estimate is lower for remaining short and mixed grass prairies, with approximately 21% of the state’s grasslands remaining. The loss is even more dire in West Texas after local farmers spent more than a century converting prairies into farmland, leaving only about 5% to 10% of true prairie land in the region, according to data from an exhibit at Lubbock Lake Landmark, which has spent several years restoring its local prairie acreage.

Although there has been a steady decrease in rangeland production in the southwest Great Plains for several years as drought conditions persistently batter the region — according to the U.S. Forest Service's most recent Resources Planning Act Assessment, published on July 24 — these grasslands have already borne the negative consequences of these changes.

Adding to their existing challenges, the region now faces a new threat of population growth and suburban development, in addition to the intrusion of woody plants — which alone claims 1 to 3% of Texas grasslands each year — further exacerbating the loss of this valuable ecosystem.

Reflecting on the underappreciated beauty of the past, local biologist Martin said when he enters the fields, he often envisions a thriving scene in North American grasslands akin to Africa’s famous Serengeti, teeming with life. Large herds of pronghorns, elk, bison and deer roamed freely across the prairies, while predators, including the now-eradicated plains grizzly bear, closely followed — a sight unlikely to exist again.

Habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation are major drivers of wildlife decline globally. The same is true in West Texas, he said.

In the Great Plains, the conversion of grasslands into croplands has resulted in the concept that Martin and other scientists call the “island biogeography theory.” This describes how fragmented landscape creates challenges for land species as it forces them to traverse long distances between suitable habitats, risking their survival due to potential shortages of food and water. Martin said these large expanses of unsuitable habitat between isolated pockets of suitable habitat further hinder the sustainability of wildlife populations in the Great Plains, which is now experiencing a major biodiversity crisis.

“What’s left of the remnants of the North Americas grasslands still try to support (that same diverse ecosystem as the Serengeti),” Martin said. “But we’ve lost a lot of that biodiversity and the historic function. I think if more of that was intact still, and people could make that connection and see the equivalency between the Serengeti and North American grasslands, they’d appreciate it a lot more.”

Why the prairies are worth saving

Once vast and abundant, the prairies now stand as a testament to the urgent need for conservation and restoration efforts. Despite their underappreciated beauty, grasslands hold immense value that extend beyond their seemingly simplistic appearance but also into ecological services, health benefits and the sustainability of wildlife.

In the last decade, many organizations have come to acknowledge the wide range of benefits that grasslands provide. For instance, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and U.S. Department of Agriculture have both introduced new initiatives aimed at conserving and restoring native grasslands since 2014. Additionally, several nonprofit organizations, like the National Audubon Society, Defenders of Wildlife, the Center for Biological Diversity and the World Wildlife Fund have intensified their efforts to protect grasslands and the local wildlife they support.

Among the most notable benefits of grasslands, Hayes said, is carbon sequestration, adding that it’s probably even better in grasslands than woodlands in unstable climate conditions, which can potentially trigger the re-release of carbon stored in woodlands through natural disasters.

“(Grasslands) are not necessarily more efficient at it,” he said. “But that carbon is stored in the prairie under the soil; whereas, for forests, most of that carbon is stored in the trunk of the tree and leaves. If you have a forest fire, over time, that carbon sink goes away, but if you have a prairie fire, all that underground carbon stays there, so you can actually sequester more, and do it more sustainably, over time in grasslands.”

(This is distinct from soil carbon capture on farmlands, or through regenerative farming, which has sparked recent controversy among some scientists who believe it has failed to prove itself a long-term solution.)

While grasslands are equally, if not more, capable of carbon sequestration, Hayes said there are several other ecological benefits that have been overlooked: flood prevention, aquifer recharge, erosion control, soil fertilization and providing habitat for a portfolio of wildlife and pollinators.

Instead of focusing on the true value that lies in the existing natural services grasslands provide, he said humans have predominantly appreciated them for how they can advance their personal interests and needs, particularly in the agriculture industry.

“This is the region that has provided the food, fiber, and fuel for this country for the last 100 years,” Hayes said. “It’s the same reason it’s a fertile ecosystem for the grasses and all the critters — for that same reason, it’s fertile for row cropping. Whether it’s corn in Iowa or cotton in the (Texas Panhandle), those being the breadbasket of the nation was arguably, to some, a good thing. But it has a downside to it, too, and we’re starting to pay for it in our loss of biodiversity and the loss of wildlife.”

Both Hayes and Martin acknowledged the importance of crop production for sustaining the human population but they also believe there's a necessary balance — and most would discover that the coexistence between nature and industry would serve the successes of both better.

"I think a lot of times people just accept it as a necessary sacrifice," Martin said. "They think they'll have to sacrifice some of this grassland to grow more crops to feed more people. And while that's true to some degree, it's necessary to keep some level of grass to keep some of those ecosystem services intact (and) to help pollinate crops to even make food production possible."

Spanning 115 counties, the High Plains, Northwest and West Texas regions are home to more than 500 rare, endangered or threatened species, according to an online database from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Many of these species, as pointed out by the regional biologist Martin, remain largely unnoticed by the public with people often unaware of their presence in the area.

Spending a lot of his time in the prairies of the Panhandle, Martin said even he didn’t appreciate grasslands fully until he was several years into the job as a biologist at Texas Parks and Wildlife. Then, as he learned their various functions and understood the system, he began to recognize their true value.

“Without the grasslands out there, helping keep the soil in place, the dust storms and haboobs we experience on a regular basis would be 10 times worse,” Martin said. “Not only is that inconvenient and sometimes a little dangerous when it’s so severe that it impairs vision while driving, but they can also be detrimental to those already struggling with respiratory issues. From a health standpoint, those grasslands are helping. They’re keeping the soil in place and reducing the severity of those wind erosion events, which is also benefiting our human health. That additional soil erosion and those additional particles in the sky would be there already if it weren’t for the prairies.”

The prairie is also part of the shared heritage with those who lived hundreds and thousands of years ago, Hayes added to the list of benefits.

The pronghorn, for instance, serves as a prime illustration of a species that natives from centuries ago considered part of the landscape but has now become increasingly rare to spot, he said. As the fastest land animal in North America, pronghorns can reach speeds of up to 60 mph, reflecting their forced adaptation to past predators — including the now-extinct North American cheetah, which were believed to have disappeared more than 13,000 years ago before the Ice Age ended — and the species' longevity on this planet.

Born in Amarillo, Hopper said she fondly remembers black-tailed prairie dogs from her childhood.

As a casual advocate for the species now, she believes very few people know the history of how Lewis and Clark documented their encounter with the prairie dogs during their journey. Since the rise of agriculture in the region, these creatures are now endangered primarily because of intentional poisoning with carbon monoxide as farmers and developers began to encroach on their habitats.

As a keystone species, the population decline of the black-tailed prairie dog has consequently resulted in Texas’ extrication of the black-footed ferret, whose primary prey was the species. It's also led to the endangerment of other local wildlife that depend on the black-tailed prairie dog and its ecological benefits, including the swift fox, burrowed owl, golden eagle, mountain plover and a wide range of rabbits, snakes, spiders, toads and other ground squirrels.

“These species are part of our natural heritage here,” Hopper said. “If we don't watch out, we’re going to lose our natural heritage.”

This story is the first in an ongoing series by the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal on the disappearance of grasslands and the long-term implications of biodiversity loss and wildlife loss in West Texas and the broader Great Plains.

This article originally appeared on Lubbock Avalanche-Journal: How grasslands became North America's forgotten ecosystem