How a 'simple' 1981 lawsuit changed mental health care in Arizona

Arizona's mental health system continues to have problems, but it's come a long way since the days when people with debilitating mental illnesses were left to fend for themselves in filthy boarding houses with no counseling, socialization or job training.

The impetus for change came from a landmark lawsuit known as Arnold vs. Sarn.

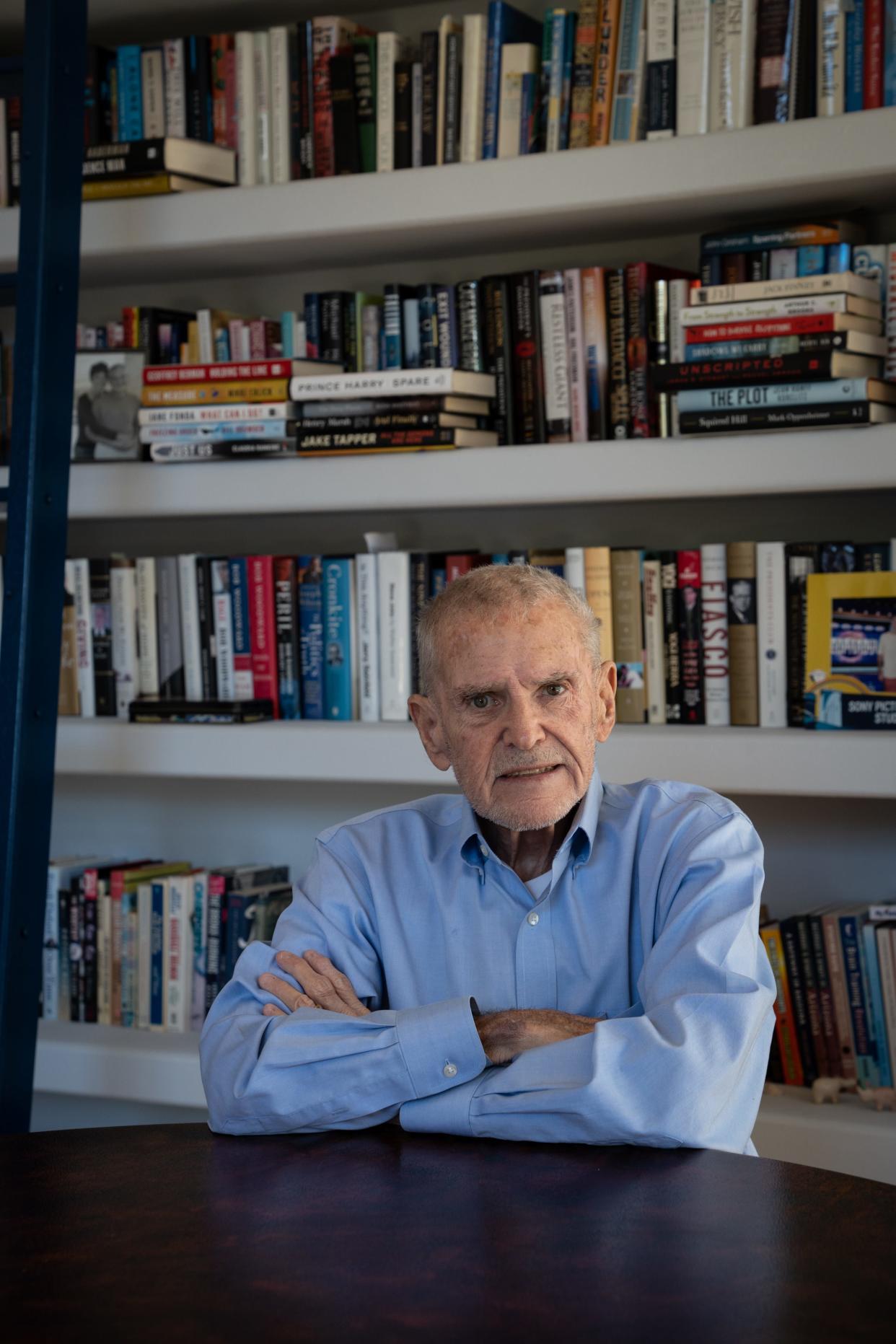

In 1981, Chick Arnold risked his job as the Maricopa County public fiduciary by suing his employer and the state of Arizona because people with mental illness were living deplorable lives. Not only was it wrong, Arnold knew it was against the law.

As public fiduciary, Arnold's office acted as guardians or conservators for about 600 vulnerable adults, including a man named John Goss, a former New York City stockbroker who had developed schizophrenia in his 20s and was living in a single room in a dirty boarding house that he found so scary that he spent his days walking the streets of downtown Phoenix.

"He lived in a place called S&W Boarding home, which was notorious. It burned down three times. He was afraid to stay there," Arnold said. "He didn't have family, and so the court appointed the public fiduciary as his guardian."

Arnold felt the state and county, per state law, were obligated to provide Goss with more support than he was getting, including a structured living situation, job training and counseling. Goss was the first plaintiff named in the lawsuit, which eventually turned into a class action.

"I balanced what I saw as my fiduciary responsibility with my employment responsibility, and that's no contest — the fiduciary responsibility prevails," Arnold said in a recent interview.

Arizona continually failed to care for people with mental illness

The supervisors fired Arnold over the now-historic Arnold vs. Sarn case (Sarn refers to Dr. James Sarn, who was director of the Arizona Department of Health Services).

A judge ultimately ruled Arnold could have his job back, but Arnold soon quit anyway to work as a mental health lawyer, which was a job title unheard of at the time, he recalled. Arnold retired in 2020 after a career of helping patients and families of loved ones who were incapacitated by mental illness.

Arnold describes Arnold v. Sarn as having a "simple" premise of forcing the state to provide a comprehensive community mental health system to people with mental illness, which is required in state statute due to a law passed in 1979. Once the lawsuit got the public's attention, the state didn't have the "collective chutzpah" to take away rights, though officials did try to get the case dismissed, Arnold said.

"This guy (Goss) was walking the streets every day because there was nothing to do. What about the socialization program? What about the recreational program? What about the housing? All of that was set out in the statute, and it wasn't being done," Arnold said. "So that was the lawsuit, a very simple case."

In 1986, a trial court ruled that the state and Maricopa County violated their statutory duty, and the Supreme Court affirmed the decision in 1989. The case ultimately stretched on for 33 years through seven different Arizona governors because of findings that the state continued to fall down on its job caring for people with serious mental illnesses.

An Office of the Court Monitor assigned to ensure the state reached compliance in its duties to people with mental illness did yearly audits of the Maricopa County mental health system that Arnold describes as "dreadful, year after year."

After one scathing audit report, Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Bernard Dougherty in a 2004 minute entry called the mental health system "shocking" and "dysfunctional," and said the audit showed "deplorable failure by the state and its agent/providers in meeting their commitments."

Among the problems were poor patient care and problems with case management.

Another blistering audit in 2009 led Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Karen O'Connor to say Maricopa County's mental health system was in crisis, Arizona Republic archives say.

A lack of housing is 'shortsighted,' Arnold says

The case was dismissed under Republican Gov. Jan Brewer, who has a family member with serious mental illness. The 2014 agreement to end the case included an agreement from the state to increase the number of Assertive Community Treatment, or ACT, teams, which are mobile teams of specialists who bring services like life skills, job help and medication to individuals with serious mental illness directly to wherever they are living.

The case technically was about Maricopa County because it grew out of the dysfunction in 1981 when it was filed. But as the case matured, its effects were statewide, Arnold said.

The settlement also included an agreement that the state would provide supported employment, permanent supportive housing and peer and family support services for people with serious mental illness. Arnold said he unsuccessfully fought to include more specifics on housing in the settlement agreement.

"What was lacking, and is still lacking through the mental health system, is effective housing. You can't recover in the absence of having a safe and secure place to live," Arnold said.

"That has never been addressed. … It's impossible to get the benefits of a system in the absence of adequate housing. Shortsighted is the kindest way of describing it."

The housing issue is extremely frustrating for Laurie Goldstein, who is vice president of the Phoenix-based Association for the Chronically Mentally Ill. Goldstein misses the days when the Arnold vs. Sarn case included a court monitor who could force the state to meet its obligations to people with mental illness.

"The court monitor was kind of the final judge. Now, there's no one to go to," Goldstein said.

As of June 30, 5,003 Arizonans were on a waiting list for permanent supportive housing through a program funded by the state general fund, and 4,674 of them were designated as having serious mental illness. The data comes from officials with the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System, which administers the housing program but does not fund it.

Another problem with mental health in Arizona right now, Arnold said, is the way the state, via AHCCCS, contracts out all its mental health care to regional behavioral health authorities. The state ought to be directly providing that care itself, much the way Arizona's Department of Developmental Disabilities does, he said.

"I believe the government has some inherent responsibilities, one of which is to provide health care, and we don't do that," Arnold said. "We contract out for it and that has been an issue that has stuck in my throat for 40 years ... The case managers in the (Arizona) mental health system are employed by a private company that contracts with another company that contracts with the state."

Emptying of psychiatric hospitals preceded Arnold vs. Sarn

Arnold vs. Sarn was in part a response to a nationwide problem.

People across the country who had been locked up in psychiatric facilities were released into communities with an aim of restoring their civil rights. But often they ended up like John Goss, who was a former resident of the state hospital and ended up living in the community, feeling lonely and without the support he needed.

"Part of the lawsuit's energy was driven by the notion of stopping institutional care," Arnold said. "His (Goss') story was a typical story at the time. People were given acute care when needed, but then released into nothing. There was no system."

In 1952, when Arizona's population was about 842,000, there were nearly 2,800 patients in the Arizona State Hospital, which first opened in 1887 as the Insane Asylum of Arizona, then State Asylum for the Insane. It is the most restrictive facility in the state for people with serious mental illness.

While the state's population has increased more than eightfold since 1952, the patient census at the Arizona State Hospital these days hovers around 316.

The drastic drop in psychiatric patients at the hospital that happened during the 1960s and 1970s was because of what's known as "deinstitutionalization," which took hold across the U.S. after the Community Mental Health Act of 1963. The act was signed by President John F. Kennedy one year after Ken Kesey published his novel "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" and at a time when medication to treat mental illness was showing more effectiveness than in the past.

The deinstitutionalization left many patients such as Goss struggling and suffering. Goss did not live long enough to see the changes that came about as a result of Arnold vs. Sarn. According to Arizona Republic archives, he died in 1983 at age 41.

"I think he just gave up," Arnold told the Republic in 1985. "He wasn't a dumb man, but he had become a frustrated one. He knew he could do more."

Reach health care reporter Stephanie Innes at Stephanie.Innes@gannett.com or at 602-444-8369. Follow her on Twitter @stephanieinnes.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: How Arnold v. Sam changed Arizona's mental health system