A Year After Singapore Decriminalized Gay Sex, Its LGBT Community Turns Attention to Family

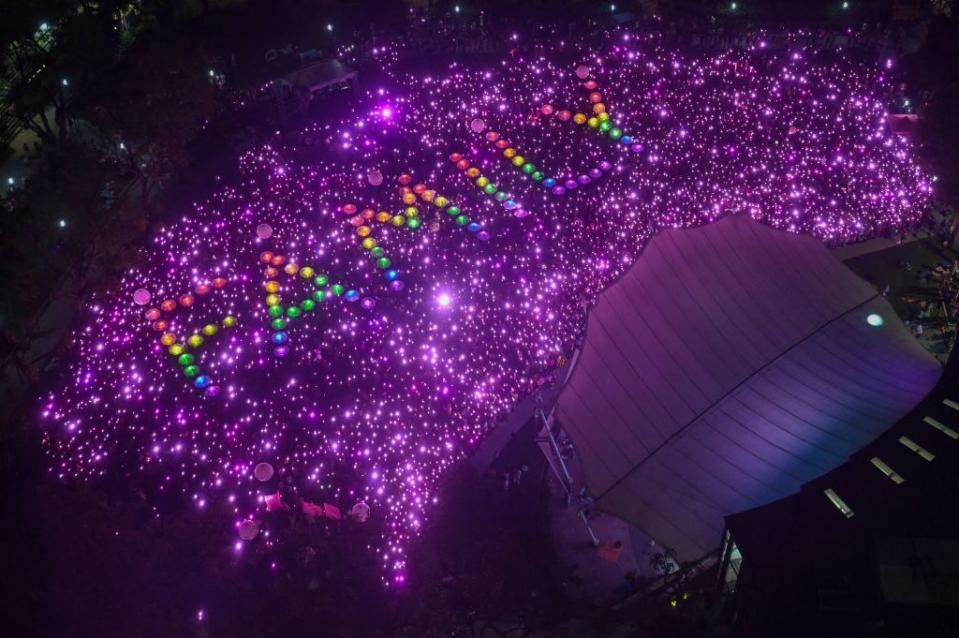

Attendees pose for photos in front of a balloon sculpture of 'Pink Dot' during the Pink Dot event at Hong Lim Park in Singapore, on June 24. Credit - How Hwee Young—EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

A two-acre green space in downtown Singapore was awash in a sea of pink on Saturday, as massive crowds gathered for Pink Dot, Singapore’s annual pride celebration. Like previous years, the air was filled with a subtle sense of rebellion as thousands congregated at Hong Lim Park—the only legal protest site in the country of 5.7 million—to support LGBT rights in the conservative city-state, notorious for its crackdowns on political dissent, which has historically also included sanctions against the queer community.

Since its start in 2009, Pink Dot has always been a mix of celebration and expressions of solidarity as well as protest against ongoing discrimination and prejudice. But this year’s Pink Dot carried extra significance, marking the first time that it’s been held after the government’s landmark repeal of Section 377A of the penal code, a colonial-era law that criminalized consensual sex between two men. Advocates tell TIME that while the repeal has brought welcome recognition to the LGBT community in recent months, queer people continue to face discrimination in various aspects of their lives, from employment to housing and the rights to starting their own families.

Read More: Pride, Against All Odds

Pink Dot’s theme this year, “Celebrating All Families,” comes as an incisive rebuttal to the government’s long standing argument that granting greater civil liberties to the LGBT community threatens the city-state’s commitment to safeguard the “traditional family.” But the theme also explores the complex familial relationships often navigated by queer Singaporeans, many of whom remain closeted from their loved ones.

More from TIME

“Pink Dot is a savior for people like us,” says Joshuani, who gave a pseudonym since he has not come out to his family. Sitting alone at the park on Saturday, wearing a pink wig and large sunglasses, the 50-year-old tells TIME that, here at Pink Dot, he does not have to hide his identity as a gay Muslim man—a secret that he has kept from his family for decades and has no plans of divulging.

Joshuani, who has been attending Pink Dot for about seven years, says his annual visit to Pink Dot is always an emotional experience. “Pink Dot opened an avenue for people like us to gather and show people who we are and express ourselves.”

Shifting focus

The first Pink Dot in 2009 wasn’t overtly political. Its aim was primarily to provide a safe space for LGBT individuals to come together in Singapore. But that changed over the years.

Phuong Nham, a Vietnamese gay man who moved to the Southeast Asian city-state about 13 years ago, tells TIME that every Pink Dot event he has attended since 2016 has been filled with explicit calls for the repeal of Section 377A, the law which critics say has long formed the basis for a host of discriminatory policies against the LGBT community.

Though Section 377A has not been enforced since 2007, its chilling effects have reverberated across society. For his part, Phuong had long avoided showing affection to his partner in public for fear of prosecution.

In 2019, as night fell upon Hong Lim Park, attendees stood together with their phone flashlights to spell “Repeal 377A.”

This year, at the end of the five-hour-long Pink Dot event, thousands of attendees similarly shone their lights toward the night sky, but this time, they surrounded the word “FAMILY,” which appeared in rainbow colors.

Last year, when Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced the repeal of 377A, he also promised to “uphold and safeguard the institution of marriage,” announcing an amendment to Singapore’s constitution to prevent the current definition of marriage (“between a man and a woman”) from being able to be challenged in court—effectively narrowing down avenues for same-sex marriage to be legalized in Singapore. The dual announcement, couched as a compromise with the country’s conservative groups, aligns with official state narratives that have long framed LGBT rights as encroaching on “traditional family values.”

Read More: Singapore’s Half-Hearted Concession to LGBT Rights May Make Real Change More Difficult

Clement Tan, spokesperson for organizer Pink Dot SG, tells TIME that the repeal was a “step in the right direction,” but not an end to their struggles.

“This year, we want to send the message that our families are equally valid and deserving of a place in Singapore,” Tan tells TIME. “Our approach from year to year has shifted but our mission has always remained the same: to bring LGBTQ+ persons closer to their families, friends, and communities, and to stand against discrimination, whatever form it might take.”

Phuong appreciates the shift in messaging, which hits especially close to home for him, he says, since he has a daughter.

“At the end of the day, the most valuable thing is family,” Phuong says. “Every gay or lesbian [couple], they have the same equal right to build their own family just as the straight couple.”

Much further to go

Just months after the scrapping of 377A, some in the LGBT community say they’ve already begun feeling tangible effects from the repeal. Benjamin Xue, co-founder of queer youth community group Young OUT Here, tells TIME that since the change, he’s seen more queer couples holding hands in public areas. More importantly, Xue says, the repeal opened doors for some queer Singaporeans to more honest conversations with older family members.

“Our parents have gotten a lot easier to talk to about queer stuff, post-repeal,” Xue says. “I think it’s just the fact that the repeal happened actually gives them a lot of breathing room and permission to talk about things with their family members. Previously, with the law, it kind of prevented them from having an open conversation.”

In a survey conducted by market research firm Ipsos last year, almost half the Singaporeans polled said that they were more accepting of same-sex relationships than they were just three years ago. Still, despite the increasing openness, the push for LGBT rights in Singapore faces an uphill battle. In another September survey from local media outlet TODAY, 62% of Singaporean respondents aged 18-35 said they wanted to preserve marriage as solely between man and woman.

Yvonne Chia, a 33-year-old queer woman who was among picnickers at the event on Saturday, says the repeal is “just one step of countless numbers of steps that we have to do.”

“I would say we’re lacking especially compared to other countries,” she tells TIME.

In nearby Thailand, which recently held a general election, an alliance led by the winning Move Forward Party signed a pact last month to legalize same-sex marriage, setting it on track to be the first Southeast Asian country to do so. It will join over 30 countries across the world that recognize same-sex unions.

But in Singapore, months before the 377A repeal last year, the government tightened its adoption laws, stipulating that couples who wish to apply for adoption must be married under laws recognized by Singapore—effectively barricading adoption opportunities from same-sex couples. Same-sex couples have also long been conspicuously left out of a nationwide subsidized housing scheme that’s meant to provide affordable housing for Singaporeans.

Jean Chong, co-founder of queer women’s rights group Sayoni, tells TIME that she hasn’t perceived many people changing how they express their sexualities after the repeal, as the day-to-day challenges faced by queer people have not magically disappeared. “There are so many issues that are intertwined,” she says. “I think the bread-and-butter things, like protection against workplace discrimination, are not being addressed.”

Increasing queer visibility has also invited much more palpable opposition. Two years ago, a local salad bar made the news when a man grabbed a pride flag it had on display and threw it at its staff. Last week, ahead of Pink Dot, the same shop shared on social media that another pride flag it had put up on its storefront was stolen—a sobering reminder of the hostile environment that queer people in Singapore continue to contend with.

“For the longest time, Singapore has been working on inclusion, diversity, and tolerance [among different communities],” says Xue from Young OUT Here. “To even talk about pure acceptance … that’s going to take a while.”