Sir Michael Colman, fifth-generation mustard heir who reinvented himself as a peppermint magnate – obituary

Sir Michael Colman, 3rd Bt, who has died aged 95, was the last of five generations of the Colman family to run the mustard business; in retirement he made a mint by reviving the British peppermint crop and creating the Summerdown brand of upmarket oils, teas and chocolate mints.

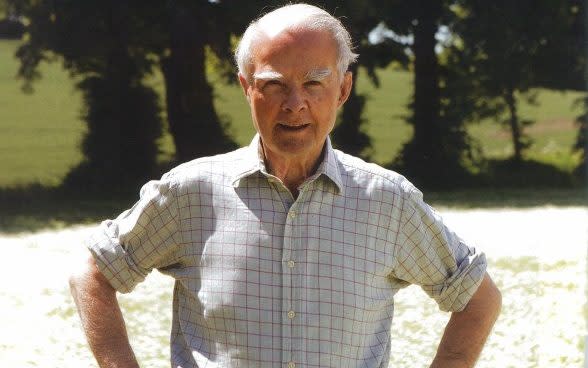

A sprightly and silver-haired figure with bushy white eyebrows, Colman exuded a courteous, old-world charm. He spent 47 years with Reckitt and Colman, including nine as chairman, but after selling up in 1995 he was determined to take on a new project, preferably centred on the farm he had inherited three decades earlier in the Hampshire Downs, where the main crop was peas.

“I never intended to go back into the food business but I was about to draw stumps,” he told The Guardian, using one of the cricketing metaphors of which he was fond. “The problem was that I was literally unemployable.”

With the price of peas falling, Colman’s thoughts turned to alternatives. “You have to have something very special to make an impression on retail, where price is a dominant theme,” he told the Telegraph magazine. “The key is not to go for the mass market but for a big enough minority.” Making high-grade peppermint oil and creating a small run of flavoured products satisfied his criteria.

British peppermint had fallen into abeyance during the Second World War. It took Colman three and a half years to choose the right strain of Black Mitcham, the traditional variety that had grown in Mitcham, south London, in the 18th century. Several more years were required to establish the crop, import state-of-the-art distilling machinery from the US and decide which products to create.

Colman took an early harvest of mint to a leading confectioner who “made a batch of chocolate creams and said they were very good, but didn’t want to take it any further”. Eventually he found a firm in Preston, Lancashire, prepared to manufacture Summerdown peppermint creams. They quickly became popular in stores such as Harvey Nichols and media interest soon followed, with Colman appearing on Countryfile, The One Show and Farming Today. “Quite a few people prefer us to Bendicks,” he said mischievously.

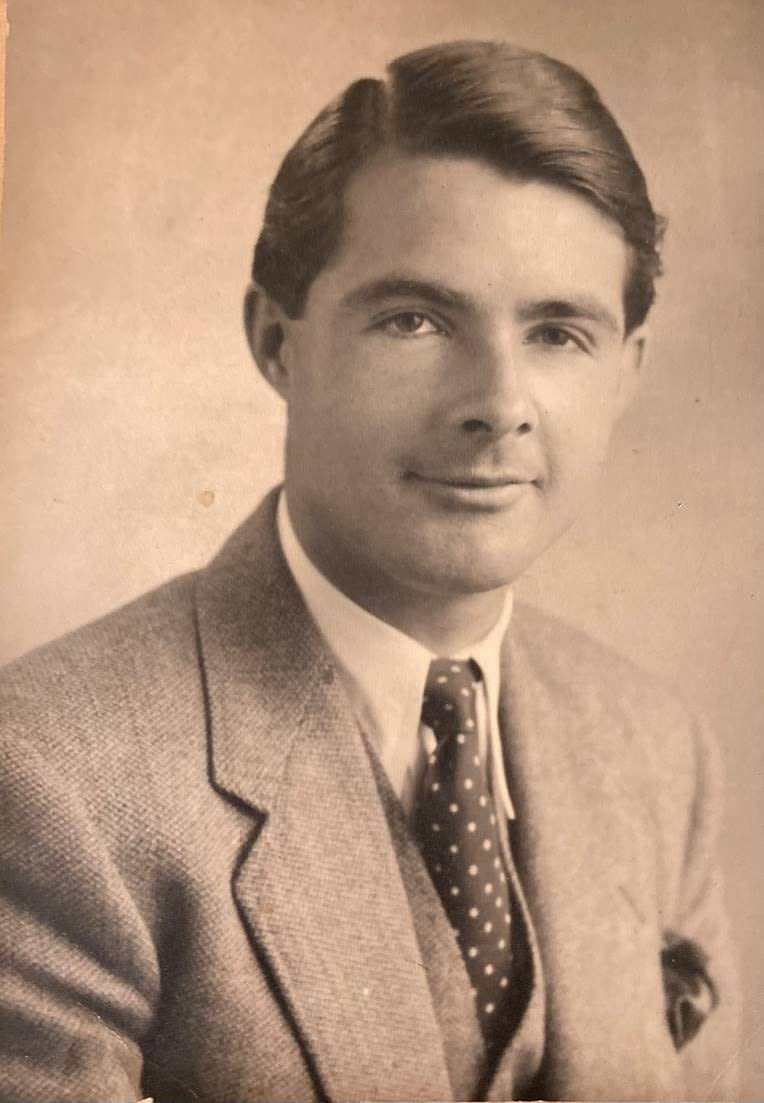

Michael Jeremiah Colman was born in Eaton Place, London, on July 7 1928, the second of three children of Sir Jeremiah Colman, the second baronet, and his wife Gwen, a scion of the Tritton baronets. The Colman baronetcy had been created in 1907 for his grandfather, also Jeremiah, who developed the mustard business into an international concern.

Colman’s Mustard had started in 1814 at Stoke Holy Cross, a Norfolk watermill, when the first Jeremiah Colman started milling mustard and flour to produce the hot flavour so beloved by the roast-beef-eating classes of England. In the 1950s the company merged with its longtime associate Reckitt’s of Hull, selling such quintessentially English products as Robinson’s barley water, Jif lemon juice, Brasso and Windolene.

Young Michael was 8 when the family moved to Malshanger, a 16-bedroom Regency pile with an arboretum, a cricket pitch and a Tudor tower built by the last pre-Reformation Archbishop of Canterbury, William Warham. He was raised in a near-Edwardian environment with an extensive staff including five gardeners and eight woodmen. He learnt to drive at 11 and never lost his love for a fine car, though during the war his mother donated the family Rolls-Royce to the War Office. It was spotted in Paris after liberation.

After King’s Mead School, Seaford, and Eton, his heart was set on serving his country in uniform. But the war ended and he had to console himself with National Service, training with the Royal Marines and serving as a captain in the East Riding of Yorkshire Yeomanry.

His father then encouraged him to knuckle down to work. “He was worried I was spending too much time riding up and down Park Lane with girls,” he told The Guardian. He started on the shop floor but was unimpressed by the management of the company whose shares formed his inheritance. Before interfering, however, he had to learn more and was duly packed off to run the overseas business. “More to get me out of the way than anything else,” he laughed.

In 1961 he succeeded in the baronetcy, inheriting Summerdown farm in Hampshire and Malshanger. He also had a house in Belgravia and an estate near Blairgowrie in Scotland, where he enjoyed walking and shooting in August.

Colman became a director of Reckitt and Colman’s overseas board in 1962. He then ran the industrial division before joining the main board. In 1970 he created the group’s first corporate planning department. Ten years later he was appointed director, making his way to the chairman’s office in 1986, all the while commuting regularly between Hampshire and Hull.

“I am not the world’s most successful businessman, but I have been able to add value and develop teams,” he told the Daily Telegraph in 1994, when planning his exit strategy for the following year. By then the value of the family’s shares and their influence was notably diminished. Furthermore, the next generation of Colmans had their own careers. “The family became a bit of an anachronism, and I expect I did too by the time I came to the end of my career,” he told Great British Life.

It was not the first time he had sold part of the family silver. The laundry dye Reckitt’s Blue had long gone, as had Cherry Blossom shoe polish, once the population at large stopped polishing their shoes in military fashion.

Colman now turned his attention to Summerdown, where mint had once grown, though for more than three decades it had been part of a pea-growing cooperative. Chocolate mints were followed by peppermint tea, which he described as an open goal because “Twinings produces quite ordinary tea”.

Then came peppermint oil, usurping existing brands with “little character”. He explained how, like wine, good quality peppermint oil needs to rest for six months, even better two or three years. “It settles and mellows,” he said. Other essential oil crops also followed, notably lavender, camomile and spearmint.

Colman, whose ancestors had been puritanical Methodists until the first baronet joined the Church of England, was appointed First Church Estates Commissioner, equivalent of chairman, in 1993. This was a time when the Church had lost £800 million in property speculation. “They’d never had a commercial man before. They were in some disarray,” he told the Telegraph magazine.

He took them out of risky investments, apologised for their past mistakes and stabilised the pensions of thousands of clergy, and declined to draw the £80,000 annual salary to which his three-day week in central London entitled him. He was particularly proud of being mentioned in George Carey’s autobiography, in which the former Archbishop of Canterbury describes how he alternately infuriated and charmed the Church’s bishops.

While his own faith was that of an old-fashioned churchman, Colman established an unlikely connection with Holy Trinity Brompton, the upmarket evangelical church in Knightsbridge. A relative had served as curate and he encouraged its members to use a wing of Malshanger for weekend gatherings. “I’m not keen on the modern diet of church music, but what they have done for young people in London is wonderful,” he told the Church Times.

He also served as president of the Council of Royal Warrant Holders, on the board of the lighthouse authority Trinity House and as a council member of the Scout Association. From 1991 to 1992 he was master of the Skinners’ Company.

Colman met Judy, the daughter of Vice-Admiral Sir Peveril William-Powlett, Governor of Southern Rhodesia, at a party for his brother’s 21st birthday. They were married at St Martin-in-the-Fields in 1955 by the Archbishop of Canterbury Geoffrey Fisher, who attracted press attention by referring in his sermon to the irrevocable nature of marriage vows at a time when Princess Margaret and the divorced Group Captain Peter Townsend’s potential nuptials were being discussed.

Judy survives him with three daughters and two sons, the eldest of whom, Jeremiah, known as Jamie, succeeds in the baronetcy.

Sir Michael Colman, 3rd Bt, born July 7 1928, died December 26 2023