Sister of Black woman killed by Capitol Police hopes riot will shed light on troubling case

In early October 2013, Miriam Carey was shot to death after what police described as a brief high-speed car chase from the White House to near the U.S. Capitol that was captured in part on video.

Law enforcement has said that she was mentally unstable and that there was not enough evidence to prove the officer's use of deadly force was excessive. Her older sister, Valarie Carey Reaves-Bey, doesn't believe that.

"They shot an unarmed woman who wasn’t a threat to anyone," she said. "She was treated unjustly. Her life was taken away from her."

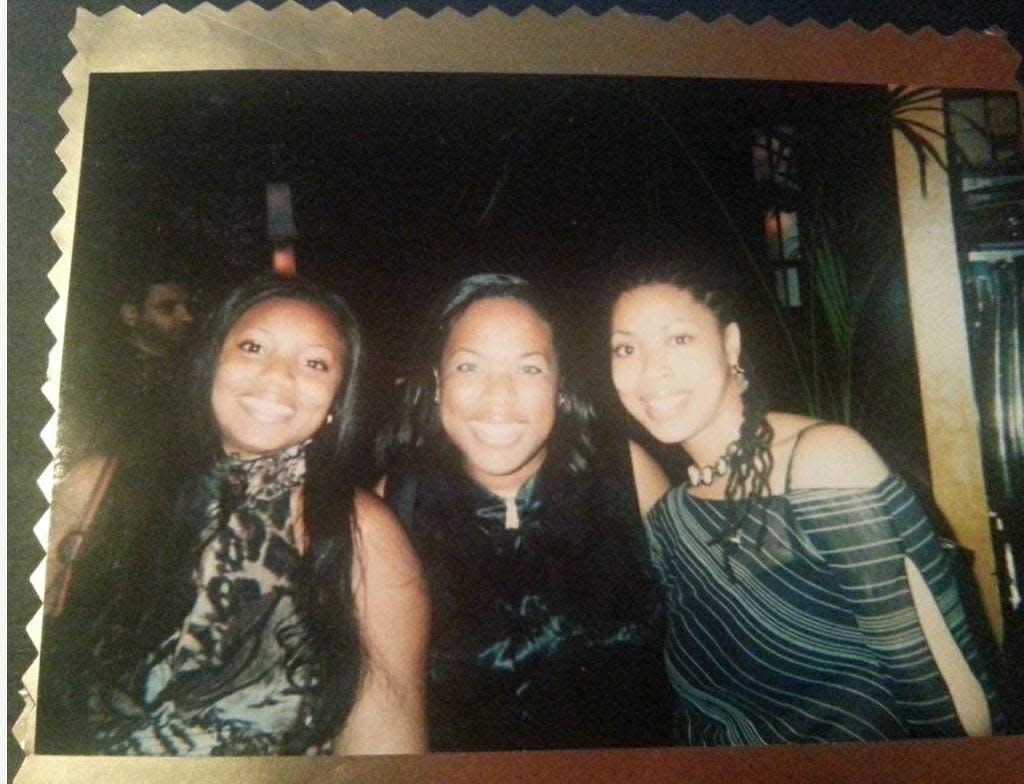

She remembers Miriam as a high achiever who was beautiful "inside and out" and loved to cook, travel and entertain. She said the 34-year-old dental hygienist, one of five sisters, lived in Connecticut but spent her weekends visiting family in Brooklyn, New York, where each sibling would sometimes bring a different dish to their mother's home. It's an image in stark contrast to the one painted by police.

Related: US Capitol riot vs. racial injustice protests: 2 systems of justice

The two sisters were planning a trip together just before Miriam was killed by Secret Service and Capitol Police on what Carey Reaves-Bey called "the worst day of my life."

Seeing rioters storm the Capitol last week dredged up feelings of sadness and grief for Carey Reaves-Bey, a retired New York City police sergeant. Still, she hopes the renewed interest in her sister's case generated by last week's violence will encourage people to sign her petition to have Miriam's case reopened.

"What happened last week in the Capitol actually is opening up the conversation as to what didn’t happen in Miriam's case," she said. "It was just a constant reminder that justice hasn’t been served for my sister."

Many Black lawmakers and activists have pointed out the apparent double standard in how law enforcement responded slowly to the mostly white rioters at the Capitol and how police interactions with unarmed Black people like Carey often result in death.

Law enforcement in the nation's capital used tear gas and rubber bullets against the thousands of people of color and their allies who took part in last year's largely peaceful Black Lives Matter protests. But police were notably absent when thousands of President Donald Trump's supporters broke into the Capitol building, forcing lawmakers and staff to shelter in place.

'Double standard': Biden, Black lawmakers and activists decry police response to attack on US Capitol

Carey Reaves-Bey and her lawyer, Eric Sanders, pointed out that a number of people have driven into security barriers at the White House in recent years and were taken into police custody.

"All of them were white except Miriam Carey, and she was the only one that had weapons drawn, discharged," he said. "Those are direct comparatives."

Carey's seven-minute car chase began on Oct. 3, 2013, when she drove her black Infiniti into a White House checkpoint where she encountered two Secret Service officers, according to a release from the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia. She turned the car around, striking an officer who was trying to block her path with a bike rack.

She drove down Pennsylvania Avenue at speeds of 40 to 80 mph, then drove into one of the traffic circles in front of the Capitol, where police blocked her exit, authorities say. She put the car in reverse, rammed into a police car behind her, then drove forward onto the sidewalk, where two Secret Service officers and a Capitol Police officer fired at her but missed.

Carey drove a few blocks away near Senate and House office buildings, where two officers fired nine rounds each at her and her vehicle crashed into a kiosk. She was taken to a hospital, where she was pronounced dead.

Her daughter, who was 1 at the time, was in the car but was not seriously hurt. A Capitol Police officer was also injured.

Sanders, the lawyer for Carey's family, disputed the police account. He said Carey did not run over a police officer or a gate and was not speeding or driving recklessly. Although family members said at the time that Carey had dealt with postpartum depression, Sanders said that there was no evidence to support that claim and that Carey was mentally stable.

Officers such as those in the Capitol Police and the Secret Service who work near secure areas are on alert for terrorist threats, which may have factored into their decision to use deadly force, said Maria Haberfeld, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York.

"The aim is to eliminate the threat, and what is the most effective way to eliminate the threat? Shoot the driver," she said. "That’s how police officers are trained."

The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia said there is not enough evidence to charge the officers involved in her death, but some experts have raised questions about the use of force.

Geoffrey Alpert, a criminologist at the University of South Carolina, said that although the threat of terrorism was probably a consideration, he questioned whether it rose to the level of "imminent threat" needed to justify use of deadly force.

"Does that justify taking a life because maybe this person is going to do something that’s illegal or threatening?" he asked. "If she weren’t near the White House or a target, a national security issue would the police have been justified in shooting her vehicle? Probably not."

Sanders said Carey's daughter, who is now 8, will be able to bring civil action against law enforcement when she becomes an adult, and the family hopes to revive the criminal charges now.

"We’re interested in two things: transparency, having these police officers be held accountable for what happened to Miriam Carey, and ultimately if there’s a civil action for compensation," he said.

For now, Carey Reaves-Bey is organizing a butterfly release for her sister's birthday in August, which will likely take place in Brooklyn in front a Black Lives Matter mural that bears her name. She, too, is still fighting for answers to why her sister was killed.

"We want the case to be reopened and fully and transparently investigated," she said.

Contributing: The Associated Press

Follow N'dea Yancey-Bragg on Twitter: @NdeaYanceyBragg

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Miriam Carey: Sister of woman killed by Capitol Police talks riot